Chinese associations in Germany focus on bringing talent back to China

China uses civil associations to lobby for CCP causes among overseas Chinese in New Zealand, Australia and the United States. The same organizations are active in Germany, but the spectrum of Chinese associations is much broader. Their focus on technology reflects China’s ambitions for industrial upgrading.

When the Association for Promotion of Chinese Culture in Germany was founded in 2015, a Chinese embassy representative urged it to “contribute to expanding Chinese soft power,” appealing to overseas Chinese’s “sincere love for the motherland.” Taking on this challenge, Liu Daiquan, a founding member, likened the overseas Chinese in Germany to a “hidden dragon and crouching tiger,” referring to their untapped potential.

The launch of the association was applauded by the State Council’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, which operates under the leadership of the United Front Work Department (UFWD) since the government reshuffle in March 2018. The UFWD, in turn, reports directly to the CCP Central Committee. Its role has been expanded markedly under Xi Jinping who has dubbed it a “magical weapon,” a term coined by Mao Zedong.

Many Chinese associations abroad pursue CCP goals

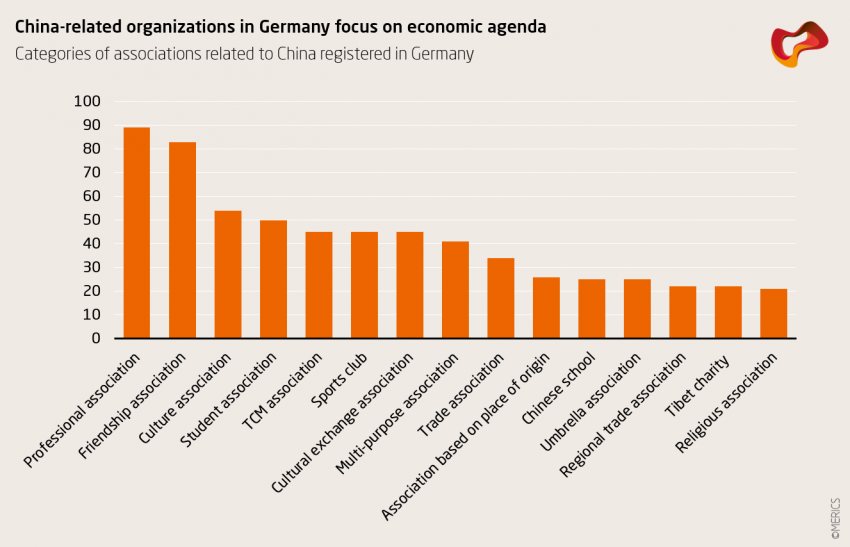

Filtering the German register of associations for China-related organizations yields roughly 900 entries. Mirroring New Zealand and Australia, they often fall into UFWD-sponsored categories. These organizations focus on instilling patriotic pride and loyalty to the CCP among overseas Chinese populations. In New Zealand and Australia, some of them have been accused of attempting to influence public opinion in their host countries.

Under the “guidance” of the Chinese embassy or consulates, several umbrella organizations (such as the All-German Association of Chinese Associations 全德华人社团联合会 or the Overseas Chinese Service Centre 德国华人华侨互助中心) maintain affiliations with Chinese women’s associations, regional trade organizations, various chapters of the Chinese Student and Scholars Association, alumni associations, as well as associations formed along professional or regional lines.

Parroting CCP propaganda, the goals of these associations include mainland China’s unification with Taiwan, as well as the pursuit of Xi Jinping’s “China dream” and “great rejuvenation,” code for the country’s quest to restore its prominence on the world stage. They aim to foster “patriotism” and “identification with the motherland” while instilling “pride in being Chinese” and “improving the image of Chinese in Germany.” Association representatives are frequently invited to Overseas Chinese Affairs Offices in China or host delegations from China. Sometimes they publicly take a stance: in summer 2016, 56 Chinese associations jointly criticized the South China Sea arbitration, emphasizing that they “stand with the motherland […].”

Emphasis on technology transfer and talent acquisition

Whereas the majority of all associations in Germany promote sports, education and culture, professional associations make up the biggest share of Chinese associations in Germany – and one third of them operate in the technology sector. This focus reflects their members’ own career interests in Germany. But Germany’s industrial strength is also seen as a useful tool for advancing “Made in China 2025,” China’s ambitious program for industrial upgrading. Some of these associations explicitly focus on “Industry 4.0,” the German project to digitize industrial production. Others focus on emerging technologies such as chip making and artificial intelligence.

Apart from gathering technical expertise, these associations pave the way for Chinese talents to return to China. For example, the Association of Chinese Computer Scientists in Germany presents itself as an influential platform that can be used to recruit talents and import technology “according to governmental or commercial demand.” The Association for Chinese Personnel Exchange in Germany provides a platform to “use the newly-gained expertise to serve the motherland as soon as possible.”

Some associations hint to technology transfer in their names, such as the Chinese R&D Innovation Union Germany. At the founding ceremony of this consortium of Chinese enterprises, ambassador Shi Mingde said that China was “in a critical stage of development from large to strong,” requiring “independent innovation capabilities.” According to Shi, the association would “serve the domestic market and add new impetus to domestic innovation.”

CCP opposition is often religious

But not all Chinese organizations active in Germany promote the CCP’s agenda. Opposition groups can also be found in the register. Associations calling for a “democratic China” are almost all linked to Falun Gong, a Buddhist-inspired meditation practice that the Chinese government calls an “evil cult.” Most provocatively, the Tuidang [“quit the party”] Service Center Germany is part of a worldwide movement encouraging CCP members to publicly renounce their membership. The only political association not linked to Falun Gong, yet critical of CCP policies, is Human Rights for China.

Most Chinese religious associations in Germany are Christian. 15 of at least 76 congregations are listed in the register; in Munich an entire Chinese school is devoted to Christianity. Religious associations provide a sense of community without political imperatives; it is here that their founders – often from Taiwan or Hong Kong – can meet their peers from the mainland on neutral grounds.

Naturally, the German register of associations does not reflect the entire spectrum of overseas Chinese activities. Most young Chinese would rather organize informally online; only associations in need of official recognition will choose to adopt a representative name and register themselves.

The UFWD has always worked on deepening ties with overseas Chinese organizations and encouraged them to express loyalty to the motherland. Yet there seems to be fresh impetus to form associations abroad: Some 43 percent of tongxianghui (同乡会) groups that connect Chinese emigrants from the same region (one of the oldest types of overseas Chinese associations) registered after Xi Jinping became Secretary General of the CCP in November 2012.

Xi has also addressed the shifting composition of overseas Chinese communities, which are increasingly dominated by students and professionals. In his 2015 speech on United Front work, Xi described Chinese students abroad as an “important part of the talent pool.“ According to Xi, they should be encouraged to “return to work or serve the country in various forms.“

Monetary and other incentives for returnees have overall been successful in the recent past. External factors such as unfavorable immigration policies in the United States can accelerate this trend. In 2017, eight Chinese students returned home for every ten still studying abroad – a record number, according to the Chinese Ministry of Education.

The growing numbers of returnees to China should worry Germany, which faces a shortage of skilled workers. It is time that German policymakers start thinking of overseas Chinese as a strategic group and offering them incentives to stay in Germany – knowing that they are in competition with Chinese organizations whose goal it is to encourage these professionals to return to China.