Smoothing market entry in a state-guided economy: China's new Private Economy Development Bureaus

The Chinese government seeks to revitalize local business dynamism with its new Private Economy Development Bureaus (民营经济发展局). While the bureaus may make the policy environment more predictable by eliminating conflicting regulations, the party still decides which firms can scale up, says Robin Schindowski.

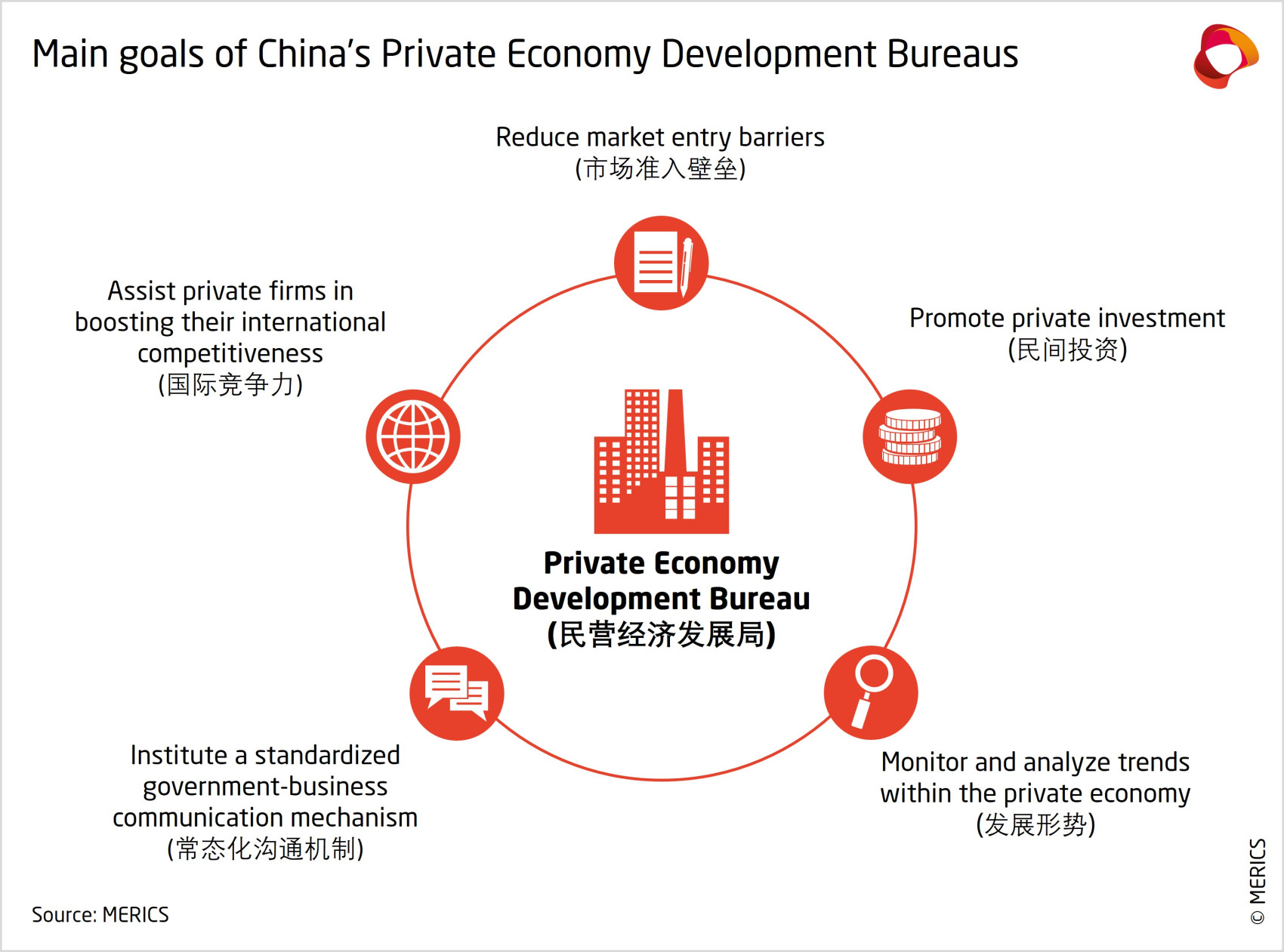

China needs a dynamic private sector to revive its economy and achieve its long-term goal of modernization through innovation-driven growth. Its new Private Economy Development Bureau (PEDB) aims to make it easier for private firms to do business – and ultimately, support these goals. Since the National Development and Reform Commission created the new department in 2023, several provinces have followed suit with their own – notably, China’s most advanced provinces, Zhejiang and Guangdong.

The PEDBs aim to better integrate private sector concerns into economic policymaking, reduce bureaucratic barriers to market entry and improve the overall business environment. By harmonizing conflicting regulations across different agencies, the PEDBs could make private businesses less reliant on personal government connections when entering a market. However, the growth stage of firms remains shaped by signaling alignment with political priorities.

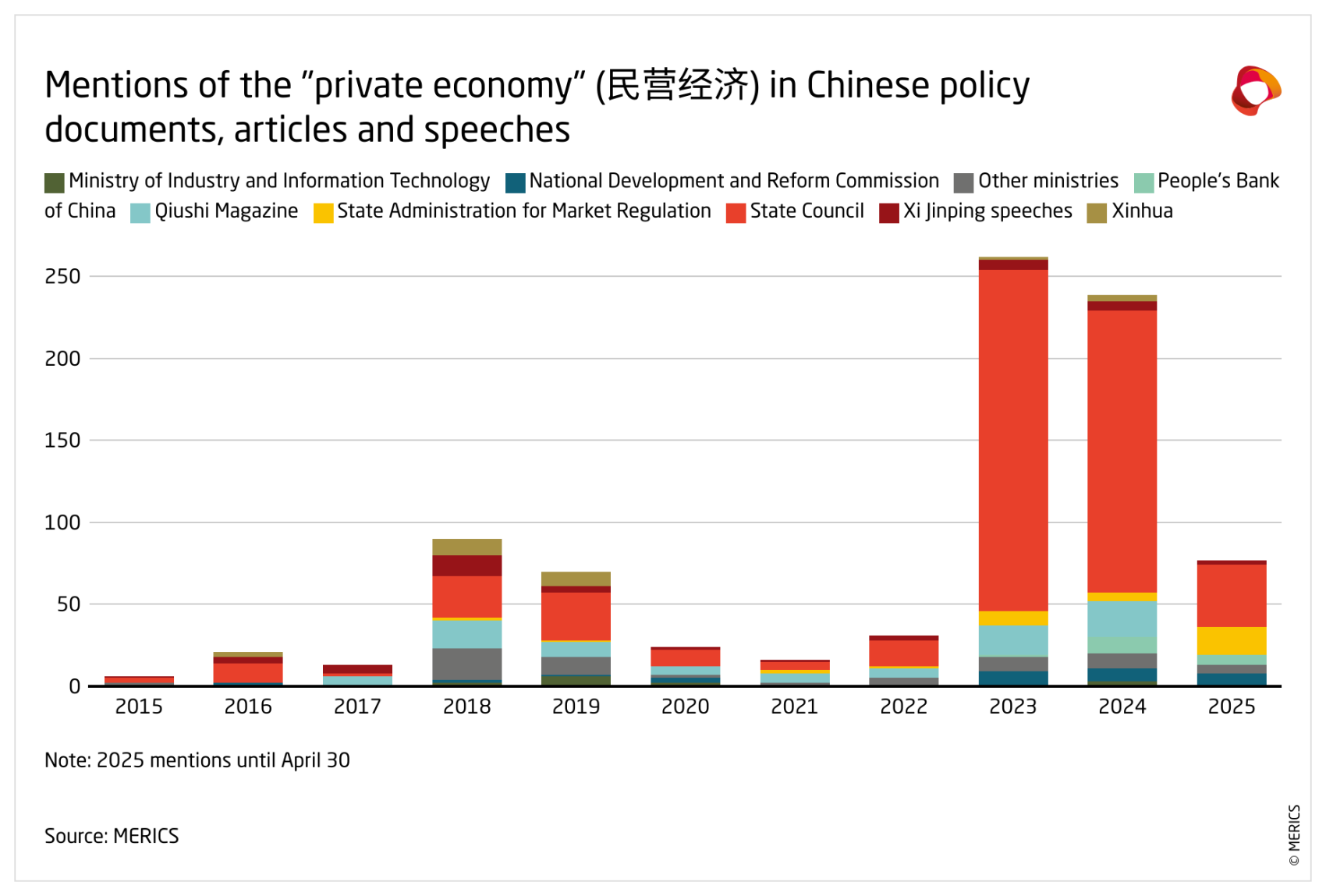

In recent years, private sector confidence has suffered due to geopolitical tensions with the United States, local government campaigns against outdated manufacturing firms (落后产能), and crackdowns by the Chinese Communist Party against the platform economy and the property sector. The PEDBs are part of a wider campaign aimed at bringing new life into China’s private economy. Since 2023, there has been a considerable increase in references to the private economy in official policy documents. In May 2025, the government also passed the first law in China to clearly define the legal status of the private sector.

One of China’s most influential economic policy advisors, Tsinghua University Professor Bai Chong-En, first floated the idea of a dedicated government department to improve the business environment for private firms in 2021. The bureau would focus on harmonizing conflicting regulations across different agencies, thereby reducing institutional costs (制度成本) and encouraging entrepreneurship. Its activities would be closely integrated into China’s broader industrial policy strategy and prioritize industries vulnerable to foreign technology chokepoints.

Fewer conflicting regulations could make market entry more predictable for firms

Just how much influence these bureaus will have over policymaking remains unclear. However, eliminating administrative barriers to market entry for private firms could solve a longstanding issue of post-Mao China. For many years, conflicting regulations across different agencies created uncertainties that forced private firms to rely on personal connections with government officials to enter new markets. These connections would grant legal security and exemptions from bureaucratic runarounds. Well-connected firms were also favored with industrial policy support and could use their political leverage to build an edge over their competitors.

President Xi Jinping’s anticorruption campaign and recent disciplinary measures for local officials have raised the costs for firms of maintaining these connections. But surveys from 2023 reveal that a lack of policy consistency continues to rank highest among the concerns of Chinese private firms. If the PEDBs can streamline laws and regulations across bureaucratic agencies, market entry could become easier and more politically neutral.

Political alignment increasingly determines a company’s chance of scaling up

At the same time, the PEDBs are part of a broader effort to combine efficient markets with a proactive state. In an interview in March, Justin Yifu Lin, former chief economist at the World Bank and another highly influential figure in China’s industrial policy debate, praised the PEDBs for providing the private economy with a po jia (婆家). In pre-modern China, a po jia referred to a mother-in-law who welcomed her son’s new wife into her household and guided her in fulfilling her responsibilities. While the PEDBs can make market entry easier, the party-state still decides which firms can scale up. And as China prepares its economy for a prolonged rivalry with the US, preferential treatment increasingly targets firms that can signal alignment with national strategic goals.

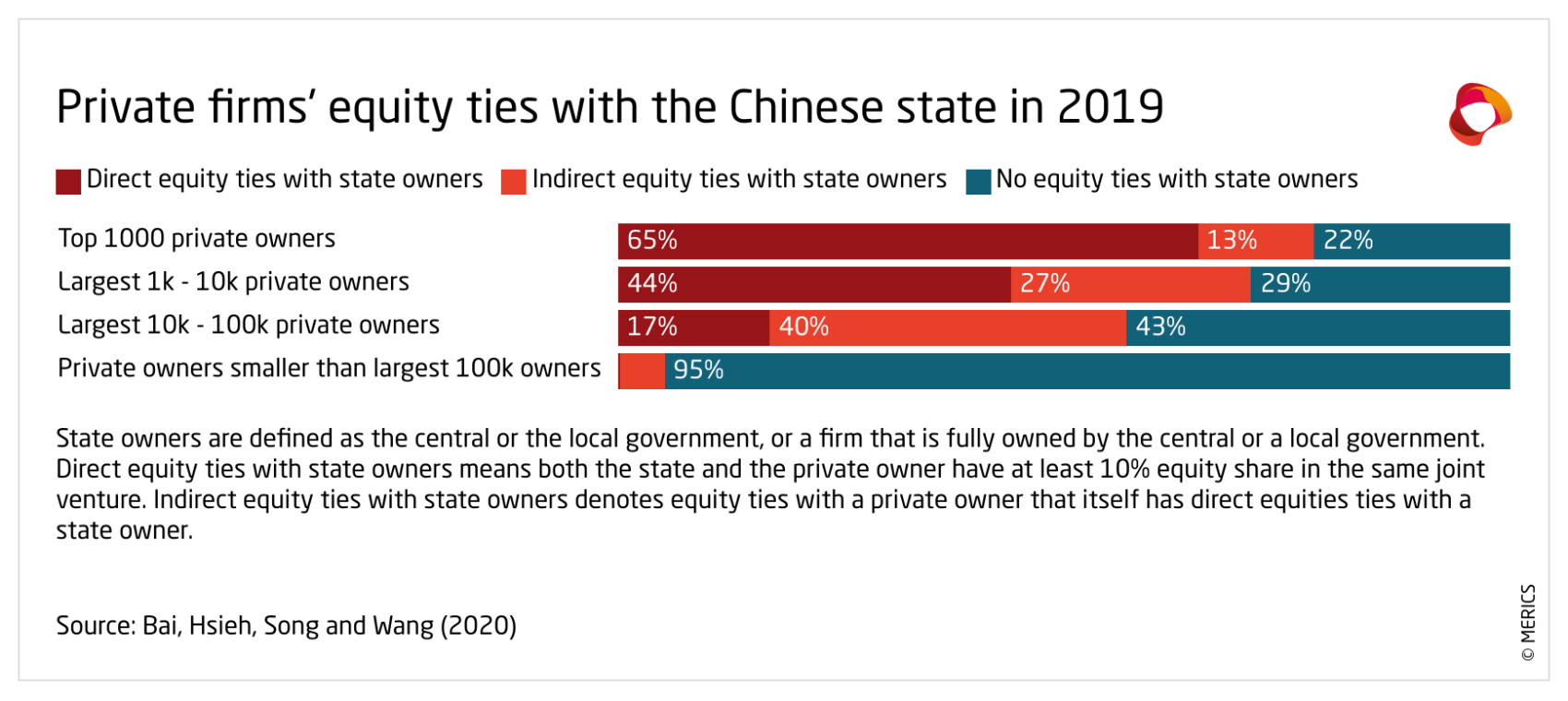

This means that the hunt for political favors will likely shift from market entry to the growth stage of a business’s lifecycle. The role of the party state in this stage has indeed expanded. The party has increased its influence over state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Party groups in SOEs now directly appoint senior managers and take part in strategic decision making. Today, more and more private firms are connected to these SOEs via their ownership structure, and state-connected private firms, in turn, invest more into other private firms, down to innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Recent policy communication also reiterates the need to enhance the role of party organizations in private businesses directly and establish a mechanism that incentivizes private firms to shoulder more social responsibility. Further, Xi’s concept of law-based governance (依法治国) explicitly serves to consolidate and strengthen party leadership. The risk is that this creates new structural distortions that incentivize firms to chase political favors instead of productive efficiency. Now, instead of business leaders sharing lavish karaoke nights with local officials, firms may seek favors from government or investment from SOEs through political signaling – for example, investing in priority sectors even if unrelated to their core competence or automating their production beyond what is economically reasonable.

Another concern is that streamlining regulations and curbing bureaucratic excess may not be enough to generate a sufficiently predictable business environment. The adherence to strong state guidance means continued exposure of firms to future policy shifts. At a dinner during a visit to China last year, the manager of a private SME illustrated this for me. Instead of an affectionate mother-in-law, he compared the government's footprint in the national economy to a pot of hot water. He explained that, as a private company, his firm must avoid the spots where the water is simmering — i.e., those sectors in which the government is active. The problem with China's current business environment is that no one knows where the water will start to bubble up in the future. Plus, the government has recently cranked up the heat so high that private firms like his will soon find themselves surrounded by boiling water with no chance to escape (四面楚歌). The regulatory environment may become more predictable, but ultimately, the party can still tighten its grip on sectors it deems strategically important.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author.