Why has the Chinese Foreign NGO Law become a non-issue in Europe?

Worries about the future of civil society organizations in China are limited to only a handful of European countries. Others put their faith in established informal ties or have subscribed to Chinese understandings of “people-to-people exchanges,” which are unlikely to be affected by restrictions on non-governmental organizations.

Considering the initial outcry surrounding both the adoption and entry into force of the Chinese Foreign NGO law, Europe has become surprisingly quiet about this issue. Media attention has abated, civil society representatives remain silent, and the only recent public mention of the law at the European Union level has been one sentence in a “Local Statement” by the EU Delegation in Beijing on International Human Rights Day: “While recognising the progress made in registering foreign NGOs during 2017, we also call on China to make additional efforts to allow foreign and domestic NGOs to register and operate freely and effectively.”

Two simple explanations for this European silence might seem plausible: The first is that implementation of the law turned out to be less draconian than expected and that the harsh Western criticism was either exaggerated or successful (or both). The second is that the EU has lost not only any leverage over China on critical issues but even its ability to speak up in defence of civil society or other self-proclaimed “values” of European foreign policy. While both explanations have some truth, a more nuanced account would highlight the structural differences among European “civil societies” as well as their implications for societal relations with China.

Lamenting the EU’s inability to speak with one voice towards China due to diverging national interests has become commonplace in foreign policy circles. However, this “lack of unity” explanation is too simplistic when it comes to a matter as complex as the new Foreign NGO Law which actually affects a wide array of foreign organizations, from citizen associations and classical NGOs to large international foundations, think tanks, and business associations.

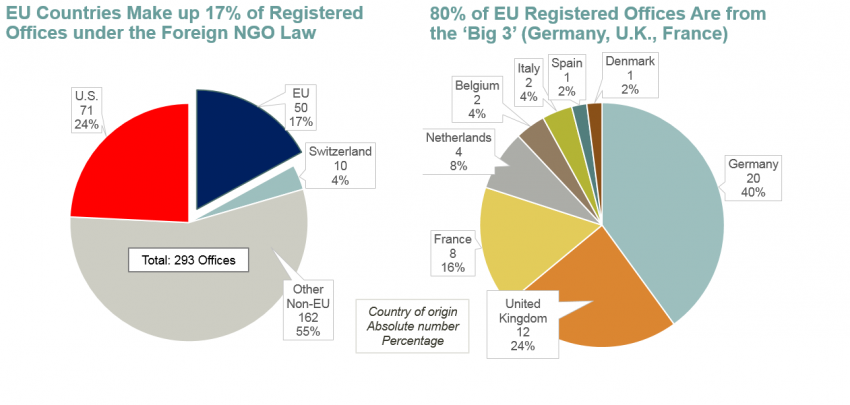

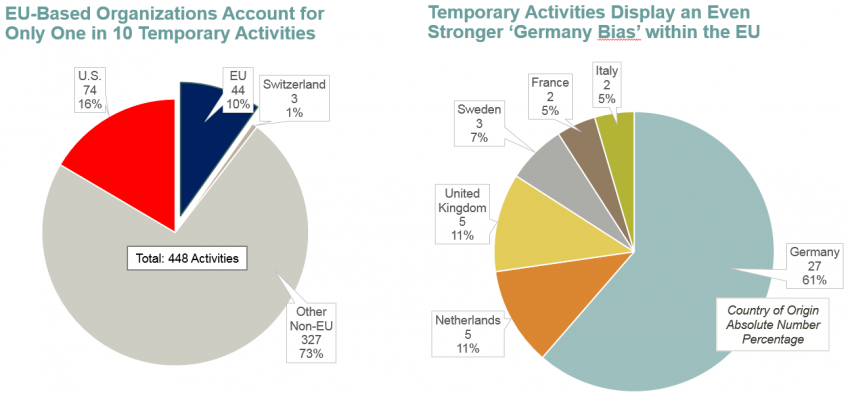

It is worth taking a closer look at the nature of European “non-governmental organizations” (非政府组织) working in and with China to see why it is hard to conceive of the law as a common European problem. Contrary to what descriptions of “Western NGOs”—particularly in Chinese debates—might suggest, the characteristics of these organizations are fundamentally diverse. To start with, only a small minority of EU member states have organizations that have been formally registered so far under the new law, with four out of five coming from the EU’s “Big 3” countries: Germany, the U.K., and France.

The picture hardly changes when looking at “Temporary Activities” filed under the new law throughout the first year—only that German organizations are even more strongly overrepresented.

These numbers give a first indication of why worries about the new law were most pronounced in Germany. Within the EU, German diplomacy was clearly the most actively committed to mitigating the effects of the law for German organizations, albeit with a strong focus on “party-affiliated foundations” (parteinahe Stiftungen). It is worth noting that these inherently political, tax-funded organizations faced massive legal problems in China at the beginning of this year, but were then suddenly registered following intense political pressure from German diplomats and politicians at all levels. This special treatment, just before Li Keqiang’s Berlin visit in late May, demonstrated the effectiveness of diplomatic pressure, but apparently also resolved Germany’s main objections with the law, potentially at the expense of other, less visible NGOs and foundations.

Due to its strong tradition of internationally active NGOs and its long-established bilateral relations with China, the United Kingdom can certainly count as the second EU country most impacted by the Foreign NGO law. Yet, the law hasn’t visibly shaken up U.K.-China relations for several reasons. First, in contrast with U.S.-Chinese strategic competition, the overall U.K.-China relationship is dominated by trade interests. Consequently, the main British concern apparently was with the future of business and trade associations falling under the law’s purview. While registration mostly went smoothly for these trade-related organizations, the new supervision and transparency requirements could cause more headaches in the future.

Second, the Brexit conundrum further pushes the U.K. government to pursue harmonious relations with China. This also means privileging uncontentious “people-to-people dialogues” over open support for more critical voices from society. Finally, British diplomacy didn’t have to handle a complicated issue like Germany’s party-affiliated foundations. While several large and long-established British NGOs such as Save the Children, ClientEarth, and Health Poverty Action managed to get registered early on, other more contentious U.K.-based NGOs—Amnesty International in particular—have long preferred to operate from Hong Kong to avoid pressure from Chinese authorities.

The strong bias towards Germany and Britain in official statistics does not mean that other European countries have no non-governmental entities working in and with China. But unlike their Northern European counterparts, those from France, Italy, and Spain are apparently opting for a more informal, continuity-based approach, which rests on avoiding the bureaucratic burdens of formal registration while relying on well-established personal contacts and the mutually perceived need for informal exchanges. In France, for instance, those non-trade organizations registered so far focus on culture, sports, and education, while many other foundations engaged in Sino-French societal exchanges enjoy the backing of high-level diplomats or former politicians. One prominent example, among others, is former Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin, who is engaged in several organizations operating in and with China without formal registration to date. Whether such an informal approach will continue to work once the unofficial one-year “grace period” for registration has ended remains to be seen. As of late 2017, however, the view that “nothing has fundamentally changed” and that “it has always been difficult to work in China” seems to prevail in France, Italy, and Spain among civil society representatives and diplomats.

The situation in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries is yet again entirely different. When it comes to state-society relations, and particularly the history and status of NGOs in the political system, many of them tend to share more common experiences with China than they do with their Western European neighbors. With domestic civil society largely oppressed during the communist past, there is no denial that the rapid growth of an active third sector since the 1990s has been supported by U.S. and EU funding in both “communist” China and post-communist Europe. Consequently, scapegoating of civil society is an easy means of rallying nationalist support in both contexts.

Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán’s infamous denunciation of NGOs as “paid political activists who are attempting to enforce foreign interests” is certainly an extreme example, which should not be allowed to overshadow the seminal role played by homegrown, bottom-up social movements in communist Europe (as well as China) in the 1980s. But the shared depiction of civil society as a “Western” concept helps understand why most Eastern EU member states have no issue with China’s stricter regulation of civil society organizations. For one, they are home to few or no internationally active NGOs whose activities could be directly affected by Chinese laws. For another, most CEE countries’ bilateral relations with China have evolved in a purely intergovernmental manner which is fully in accordance with Beijing’s understanding of “people-to-people exchanges,” i.e. top-down-initiated, government-controlled bilateral exchanges mainly dealing with “soft” topics like culture, education, or tourism. Furthermore, from a Chinese domestic perspective, the Foreign NGO Law’s primary purpose was to regulate “Western” NGOs, whereas CEE countries fall under the framework of “South-South Cooperation,” supposedly excluded from strategic competition.

With many of the EU’s central and eastern member states additionally enchanted by the lofty investment promises of China’s Belt and Road initiative and keen on further developing the Beijing-initiated “16+1” cooperation format, the EU’s shrinking capacity to act on potentially controversial issues seems hard to negate. But even without such deft Chinese diplomatic exploitation of Europe’s internal divisions, the sheer diversity of country-specific situations regarding relations with China requires far more internal EU coordination and mutual trust-building between Europeans before they will be able to speak with one voice on issues such as the Foreign NGO Law.

This article was first published on January 3, 2018 by the China NGO Project, an initiative by our partner organization ChinaFile.