Party-state capitalism under Xi: integrating political control and economic efficiency

by Nis Grünberg

You are reading chapter 1 of the MERICS Paper on China "The CCP's next century: expanding economic control, digital governance and national security". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 1 of the MERICS Paper on China "The CCP's next century: expanding economic control, digital governance and national security". Click here to go to the table of contents.

Key findings

- For China’s leaders, the CCP’s centenary serves not only to highlight the party’s own rags-to-riches story, but more broadly China’s economic and geopolitical rise.

- Under Xi, the idea of China converging towards liberal economic systems is thoroughly dismantled. China wants to present the world with a better governance model able to control and resolve the dangerous imbalances caused by laissez faire capitalism and poorly regulated finance.

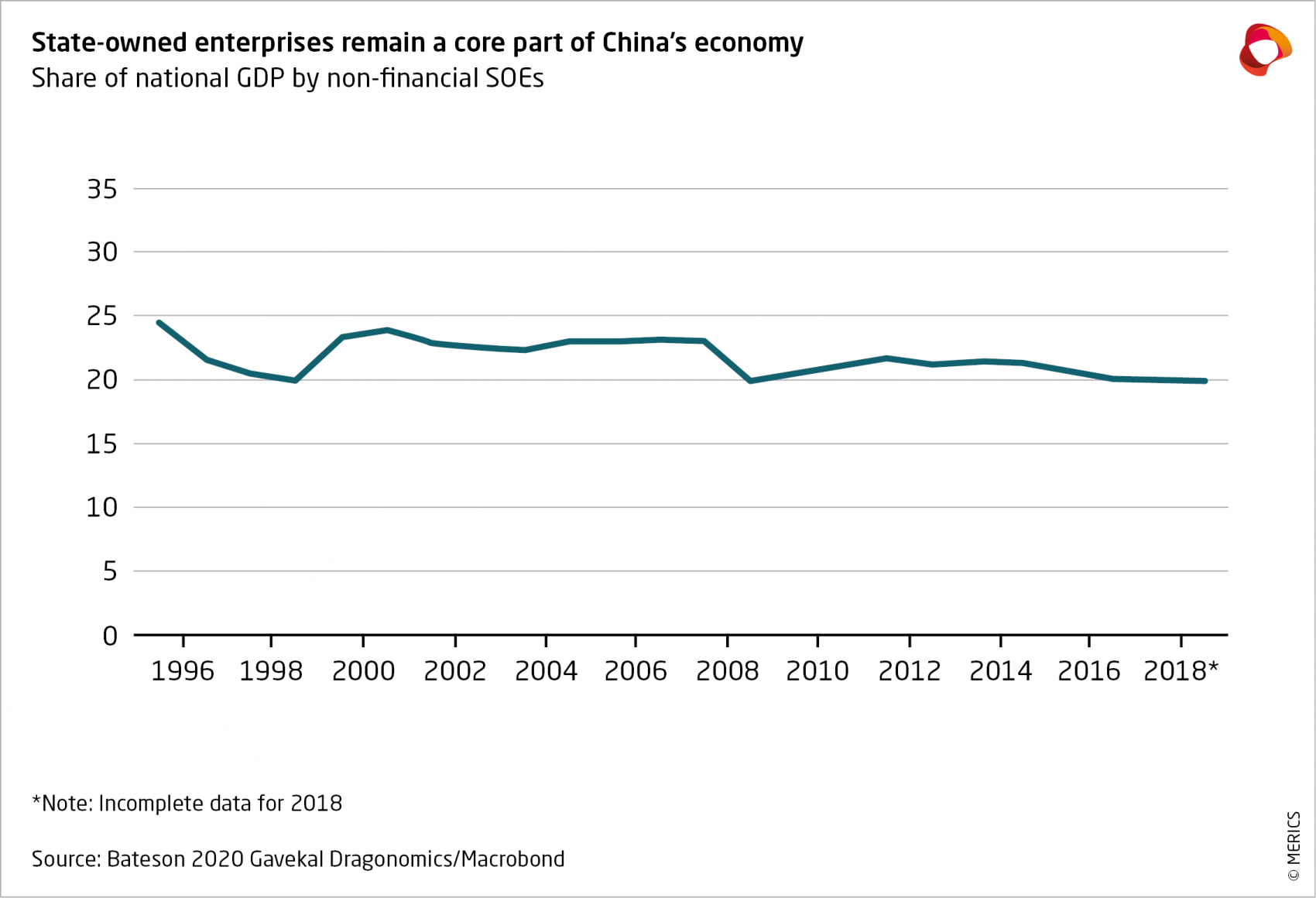

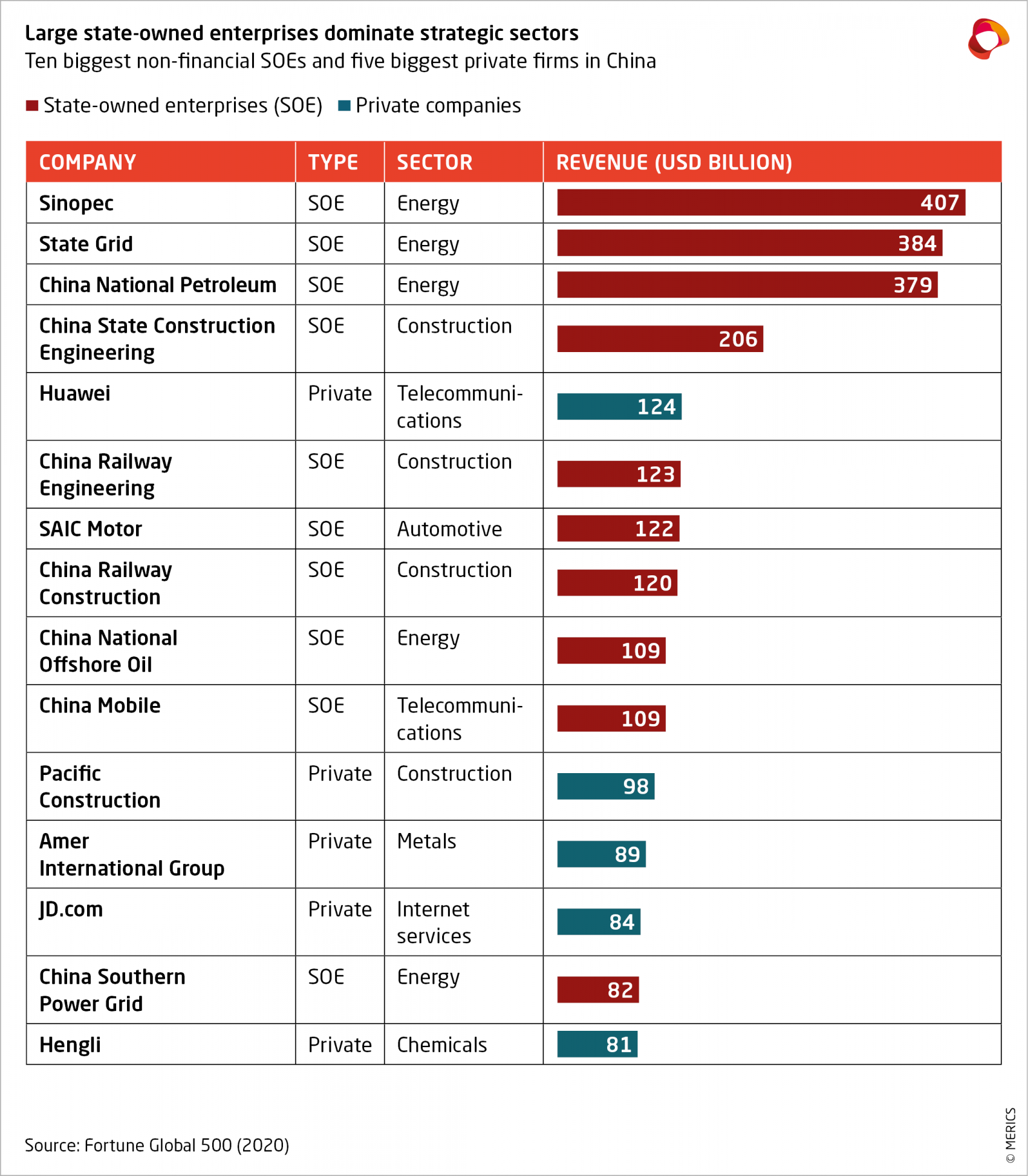

- The public economy, led by state-owned enterprises, remains crucial to China’s socio-economic fabric. The private economy is much larger, but SOEs dominate strategic sectors and are considered vital for the national interest.

- China will unlikely nationalize private players like Alibaba, Tencent, or Huawei. But Beijing has signaled that tolerance of their dominant market positions is dependent on their active alignment with party politics.

- China’s current direction of travel is clearly towards a business environment in which CCP leadership and objectives point the way.

- In its systemic competition with liberal capitalism, Beijing is convinced that its political control, flexible economic governance and technological breakthroughs will eventually lead it to superpower status.

1. Turning 100, the CCP can celebrate its economic power

As it celebrates its 100th anniversary, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is stronger than ever before. It is firmly in charge of the world’s second largest economy – one set to overtake the United States in only a few years’ time. For China’s leaders, the CCP’s centenary serves not only to highlight the party’s own rags-to-riches story, but more broadly China’s economic and geopolitical rise. In this official narrative, economic growth and development come hand in hand with party leadership. “Without the CCP, there is no new China” (没有共产党,没有新中国), as the saying goes.

The CCP’s guiding principles of party hegemony and the primacy of politics over economics are long familiar, indeed today’s “Xi Jinping thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era” has many things in common with the party discourse of the last decades.1 But the enormous authority of the General Secretary of the CCP (and President of the People’s Republic of China) and the means available to him through a modernized party-state apparatus mean that Xi has more power than any Chinese leader before him to put many of the party’s ideas into practice.

In a speech delivered in early 2021, Xi pointed out that China has entered a “new development stage.”2 The way Xi’s administration now governs the economy has become so distinctive that scholars have shifted from talking about the familiar state capitalism to a more recent “party-state capitalism,”3 or from thinking in terms of “China Inc.” to “CCP Inc.”4 Xi’s unprecedentedly powerful, ideology-infused political steering of the economy is establishing a new economic order.5 This party-state capitalism is characterized by centralized leadership, a hybrid economy that blends market capitalism with macro-economic development plans based on objectives outlined by the center, and private and public economic actors working with or alongside each other in various constellations.

Xi and the leadership he has gathered around him consider the system they have forged to have withstood major economic and social shocks – the result of financial crises or the Covid-19 pandemic – better than many so-called developed economies. Beijing sees the party state as the better governance system and party-state capitalism as the better economic model. Modernization and economic growth seen as the success story of party-state capitalism have lent Xi’s regime significant financial means and legitimacy. The material development success, growing technological capabilities, and faith in China’s ability to withstand major shocks comparatively well (such as the global financial crisis and Covid-19), are fueling the conviction of the party state’s systemic advantage.

Under Xi, the idea of China converging towards the liberal economic systems is thoroughly dismantled, and Beijing is entrenching its party-led and state-driven economy. In his succinct analysis of the global financial crisis, Liu He (currently China’s most senior economic policy planner) diagnosed that “the world is expecting the arrival of a new theory” for economic governance. He also channeled Henry Kissinger, predicting a new world power every century.6 This is what China wants to present the world with, at the CCP’s 100th anniversary: a better governance model able to control and resolve the dangerous imbalances caused by laissez faire capitalism and poorly regulated finance, and economic governance disconnected from political and social priorities.

In its purest, ideal type form the vision is one of China governed as one social unit in an organic relationship (under hierarchy) between the party state and the economy. This new governance model is seen as more resilient and adaptive than the fragile liberal economies of the West.

Party-state capitalism is geared towards stability and control over the domestic arena, rather than solely market efficiency. China’s leaders are willing to grapple with this continual trade off because they see this systemic feature as an advantage in a time in which the international order is beginning to shift. A more organic integration of economic governance under political leadership is not only for more control, but it gives China more adaptiveness in the face of “black swan events:” sudden critical and unforeseen shocks to the system. It enables the leadership to mobilize economic resources towards political ends much more directed than most other systems. Looking at major Western economies struggling to deal with Covid-19, Beijing is ever more confident it will come out top in what it deems deep systemic competition with liberal democracies.

Finally, the “new era” also comes with a “new pattern” of global integration. The Dual Circulation concept again takes national economic priorities – “the great internal cycle” – as the foundation for policy making. China is and remains highly integrated in the global economy, but in the new era its ascent as world power will mean the economic center of gravity will shift to China. This entails more bargaining and norm-setting power in supply chains, technology, finance and economic governance in ways that aid, or at least don’t harm Chinese domestic interests.

Of course, there are limits to the CCP’s control and its all-of-society governance capabilities, especially in the economy. But the direction of travel of the past years show it is unwise to disregard Beijing’s willingness and ability to implement political plans more forcefully than before. In the economy we see these shifts unfolding in important ways, as will be discussed in this chapter.

2. Building an economic order around party leadership

The party leads, the market allocates resources, is the often-recited logic of China’s so-called “socialist market economy”. It insists on the “public economy as the backbone of the economy,” and dominant State-owned enterprises (SOEs), but allows for market capitalism to exist at the same time. For most parts, China’s economy is a highly competitive market economy, but the party state reserves its rights to control strategic sectors, support priority industries, and use its ownership and control rights in the public economy, as well as regulatory and financial incentives to steer development towards key political objectives.

2.1. The CCP cements state-owned enterprises as the economic foundation

Direct control and natural monopolies in strategic sectors have long been a feature of China’s economy. Controlling energy, information networks and other types of infrastructure ensures Beijing’s ability to govern China as a whole. The country’s leaders value the role of SOEs as macro-economic levers, and developments over recent years show that SOEs remain the backbone of Xi’s party-state economy. When the job market slumped in early 2020 due to the Covid crisis, the “national team” of central SOEs were told to jump in to boost employment and aid pandemic fighting efforts.7

The public economy, lead by state-owned enterprises, is crucial to China’s socio-economic fabric. Employing at least 60 million people, SOEs are a corner stone of the job market. They contribute 20-25 percent to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), a figure that has remained constant for many years as the Chinese economy and SOEs grew in co-step to become significant global players today.11 The private economy is much larger, but SOEs dominate energy, transportation, public utilities and other strategic sectors where they hold “natural monopolies”12 considered vital for the national interest. In these sectors 96 “national champions” are overseen by the central state, while leaders are vetted by the central party apparatus.

SOEs are still less efficient and less profitable than private companies. SOE reforms have long been on the agenda, but efforts to establish modern corporate governance and increase efficiency are moderated by more important political considerations. The Third Plenum of the CCP’s 18th Congress in 2013 declared a “decisive role of the market in resource allocation.” Two years later, new guidelines outlined a modern corporate governance with Chinese characteristics and stated that party leadership should be “the core of the corporate governance system.”13 This latter move gave each SOE’s party group, in effect its highest leadership body, formal power of decision over strategy, major investments, leadership personnel, and issues relating to national security.

In 2020, a new regulation again stressed the requirement that SOEs must establish party groups.14 China’s SOE reform does not entail privatization, equal treatment, or independent corporate governance. SOEs are seen as important state asset meant to protect and increase state-owned capital. While commercialization and profit-driven strategies are part of the reforms, differential treatment, political involvement and beneficial policies will remain in place.

Party leaders are meant to serve as directors on company boards, further integrating party leadership and corporate governance in SOEs. For them, the political utility of SOEs as owners, operators and investors in infrastructure and strategic sectors is often more important than mere profit.

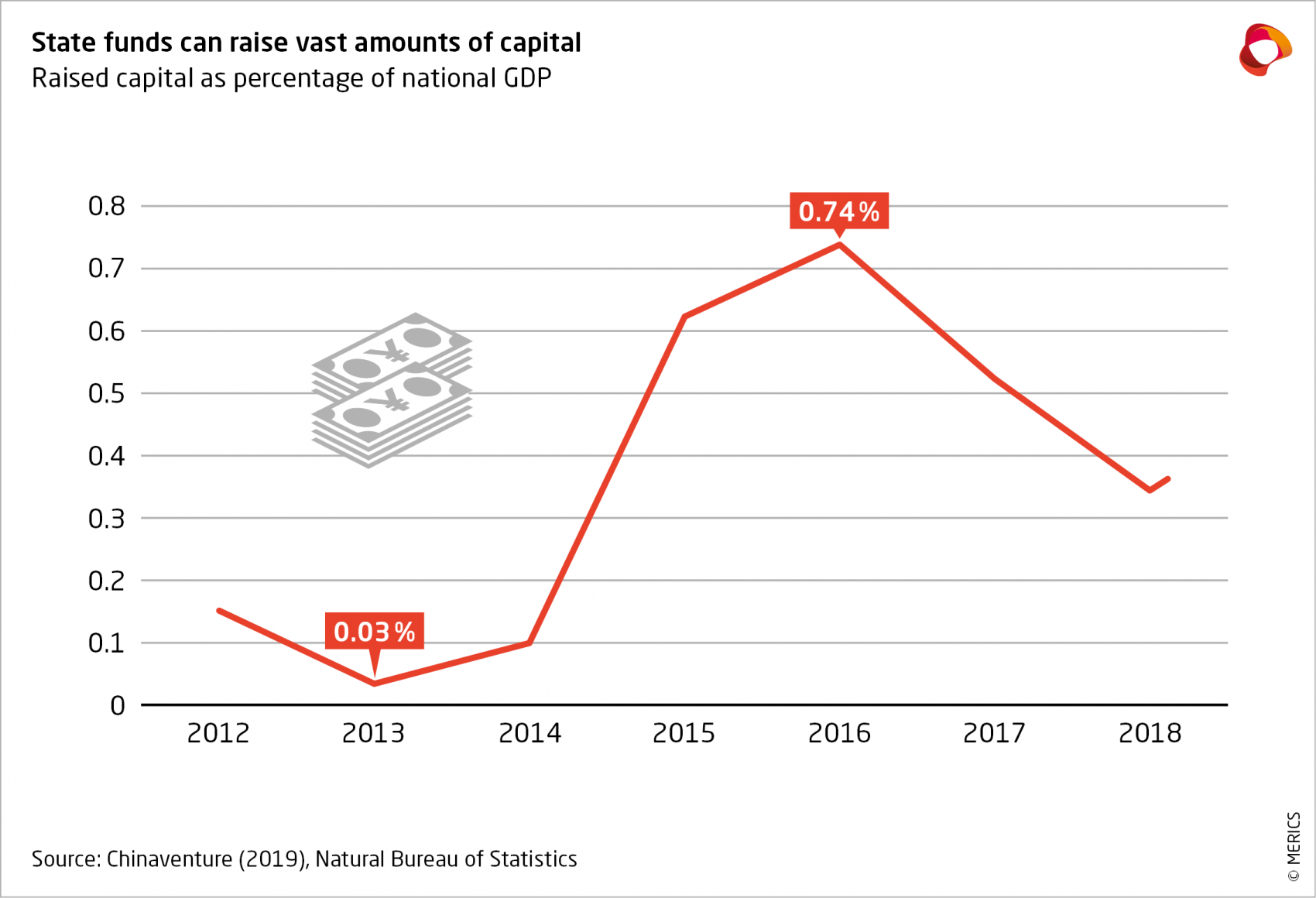

Party-state control over SOE’s capital allows targeted investments in an increasing number of ways. While China continues to support state-owned enterprises and their strategic industries, large state-owned investment funds are playing an ever-bigger role in advancing industrial policy and development targets beyond the scope of SOEs. Capital earmarked to support industrial-policy targets (including those of the Five-Year Plans) is channeled through specialized 'state guidance funds' (政府引导基金), set up to raise funds for investment into priority industries. There are over 1700 of such funds controlling around 700 billion USD (see exhibit 3).15

The perhaps most prominent example is the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund that was created in 2014 and charged with developing a domestic semiconductor industry.16 In two fundraising calls it has raised over 50 billion USD, investing in both private and publicly owned companies. The second round was also followed by an incorporation of the fund.17 Fund managers are evaluated by return on investment, but the fund is a hedging mechanism as much as generator of returns.

As an investor, the party state wants to back multiple players in the sector and work towards a clear political objective – developing a homegrown semiconductor industry. Compared to direct subsidies and cash-gifts to SOEs of the earlier days, the evolving state guidance funds also show how Beijing is learning and trying to tweak its development steering mechanisms.

The rise of state-owned investment funds is meant to bring more market discipline to allocating resources to high-impact projects, but they have not been a silver bullet against poor investment returns. Their ultimate goal is not profit maximization, but technological development and breakthroughs in priority industries – as defined by the party-state leadership, e.g., via Five-Year Plans.

There are many reports about bankruptcies, illicit uses of funds, and failed investments due to poor due diligence.18 Tens of thousands of companies in the semiconductor industry have been established in the last few years alone, encouraged by the vast amounts of capital that sprung out of government support for the sector.19 Beijing bets on the potential of a few players achieving technological breakthroughs in strategic emerging industries, a feat that will outweigh the economic cost of poor investments with no or little returns.20

Party-state capital is also being used strategically to absorb the risks of downward swings in markets. Economic shocks such as the global financial crisis and the collapse of large conglomerates like Anbang and HNA Group have shaken China’s financial system and rattled the leadership, which has made financial risks a top priority for regulators.

When an equity crisis sent stock prices tumbling in 2015-16, Beijing realized it could not control China’s increasingly complex financial markets. SOEs and state investment funds were ordered to step in to stabilize collapsing stock prices that were endangering dozens of listed companies and millions of private investors. Initially seen as providing a quick fix for market turmoil, state entities have since not retreated from the stock market and continue to invest in public and private companies.21

2.2. The CCP has an eye on strategic emerging industries

Alibaba, Huawei, Tencent, Bytedance and other private companies in China have emerged as industry leaders in sectors like information communication technology (ICT), artificial intelligence (AI), media and fintech. They are driving innovation in technology that also powers official information service platforms and have developed into system-relevant players through their economic size alone. They are also central to China’s digital infrastructure – infrastructure that provides the party state with the means to build up its own surveillance and governance capacities (see chapter by Drinhausen and Lee) – and allows political elites to benefit from the huge profits of these new industry leaders.22

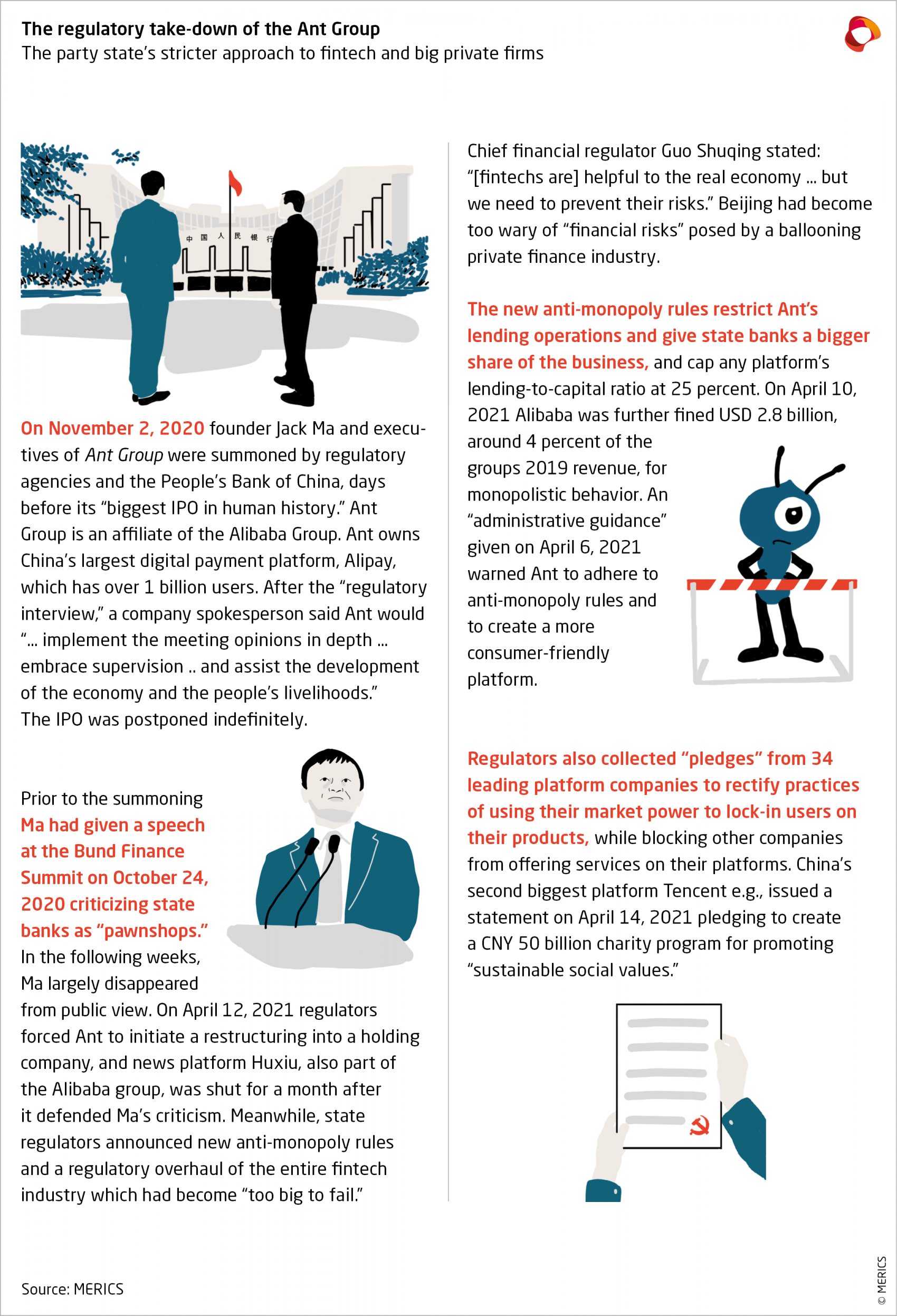

China will unlikely nationalize useful private players like Alibaba, Tencent, or Huawei. But Beijing has signaled that its tolerance of their dominant market positions in strategically crucial sectors like fintech, media, and ICT is dependent on their active alignment with political priorities, including preventing financial risks. For example, the consumer loans market is worth over CNY 14 trillion, and popular microlender Ant Group alone has around CNY 1.7 trillion worth of consumer loans, enough to make regulators nervous about financial risks and potential black swan events in the fintech sector.23 Their answer has been a mix of more political oversight, stronger regulation, and intense anti-corruption efforts in the state-dominated banking and finance sector.

The implicit deal – letting China’s private national champions do what they do best as long as they comply with party state rules and norms – seems to be approaching its limits. Companies such as Alibaba have become so large that they are considered by regulators to be “too big to fail” and so have potential to become systemic risks.24

At the same time, industry leaders and innovators in the private sector are enlisted to achieve the technological breakthroughs and research in frontier technologies and strategic emerging industries, outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan for 2021-25.25 Companies such as Huawei and Baidu are vital parts of the technology development clusters evolving around state plans.

As a result, the party state finds new strategies to better monitor and control them. As discussed above, state-owned funds have increased their investments in and cooperation with private companies, especially the larger ones. It is also using equity stakes to deepen its ties with – and information disclosure from – corporations in the private sector. This gives the party state deeper insights into new markets and the private sector, while the entrepreneurs it has co-opted gain access and secure special deals like tax breaks.2

2.3. The CCP wants a seat in corporate board rooms

The party state is pursuing the integration of party organizations also with private enterprises. Party leadership is being written into corporate charters and governance systems, and regulation has become tougher and more ideologically informed.

China’s Company Law requires any company with three or more party members to establish a party group. Smaller private companies long viewed this as a meaningless formality, but under Xi the institutionalization and use of party groups for political mobilization is rising. More than 70 percent of all private companies have established party groups, according to the CCP.27

Although they do not have formal decision-making powers in private companies, party groups are meant to play a consultative role in the “modern enterprise system with Chinese characteristics.”28 Regulations encourage the groups to recruit their leaders from company management or people representing the “business’ backbone” (业务骨干) to integrate corporate officers and the company’s CCP leadership.29

New forms of party-state interaction with private firms are also being developed. The city of Hangzhou in 2019 started a pilot program that dispatched 100 CCP cadres as “government affairs representatives” to 100 private firms, industry leaders such as Alibaba and Geely among them.30 The program’s stated aim was to smoothen these companies’ relations with local authorities. But it also institutionalized and deepened the formal links and information channels between the party state and the private sector. Other localities have since established similar programs.31

Party groups in the private sector recently have been urged to take a proactive role in shaping a sense of mission and political awareness within their companies. In September, the CCP issued a new policy calling upon its United Front Department, which is charged with integrating and aligning non-party organizations and groups with the “party line,” to increase its ideological engagement with the private sector.32

In a speech published two days after the document was released, the vice chairman of the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, Ye Qing, laid out the intentions behind:

“Private enterprises can establish a monitoring and auditing department under the leadership of the party organization. This department will be responsible for supervising the implementation of the enterprise’s compliance with laws and regulations as well as company management structure, alerting and educating management and employees [about problems with the former], supervising unusual behavior on the part of employees, investigating and handling disciplinary violations and rule-breaking, and to conducting risk assessments in key business fields and other related work.”33

But the motivations for more oversight are also about stability. Chen Yixin, chairman of the Central Political and Legal Commission, the party organization overseeing legal issues, underlined the need to better regulate and control online platforms and financial services companies, in particular also in order to “prevent financial risks from spilling over into areas of social stability or even political security.”34 Fine-tuning the regulatory framework to reflect changing economic risks and social imbalances is an important move in poorly regulated and fast-growing industries.

The evolving approach to the burgeoning private sector follows a control-performance logic, in which the former is being reinforced after years of relatively loose regulation, especially of China’s ballooning financial industry. As private fintech companies have forged a valuable business sector of significant economic scope and growing strategic importance for the economy, Beijing is pushing for better regulation, more effective monitoring and stronger risk control – both political and economic.

2.4 The CCP calls for corporate allegiance

The integration of the party state and private companies through equity links and closer supervision through regulatory changes have been flanked by an ideological push from Beijing that invokes the patriotic role of entrepreneurship. Xi Jinping in July 2020 reminded business leaders of their need for “patriotic sentiments” and pointed out that “great entrepreneurs have a high sense of mission and a strong sense of responsibility for the country […] linking business development with national prosperity.”35

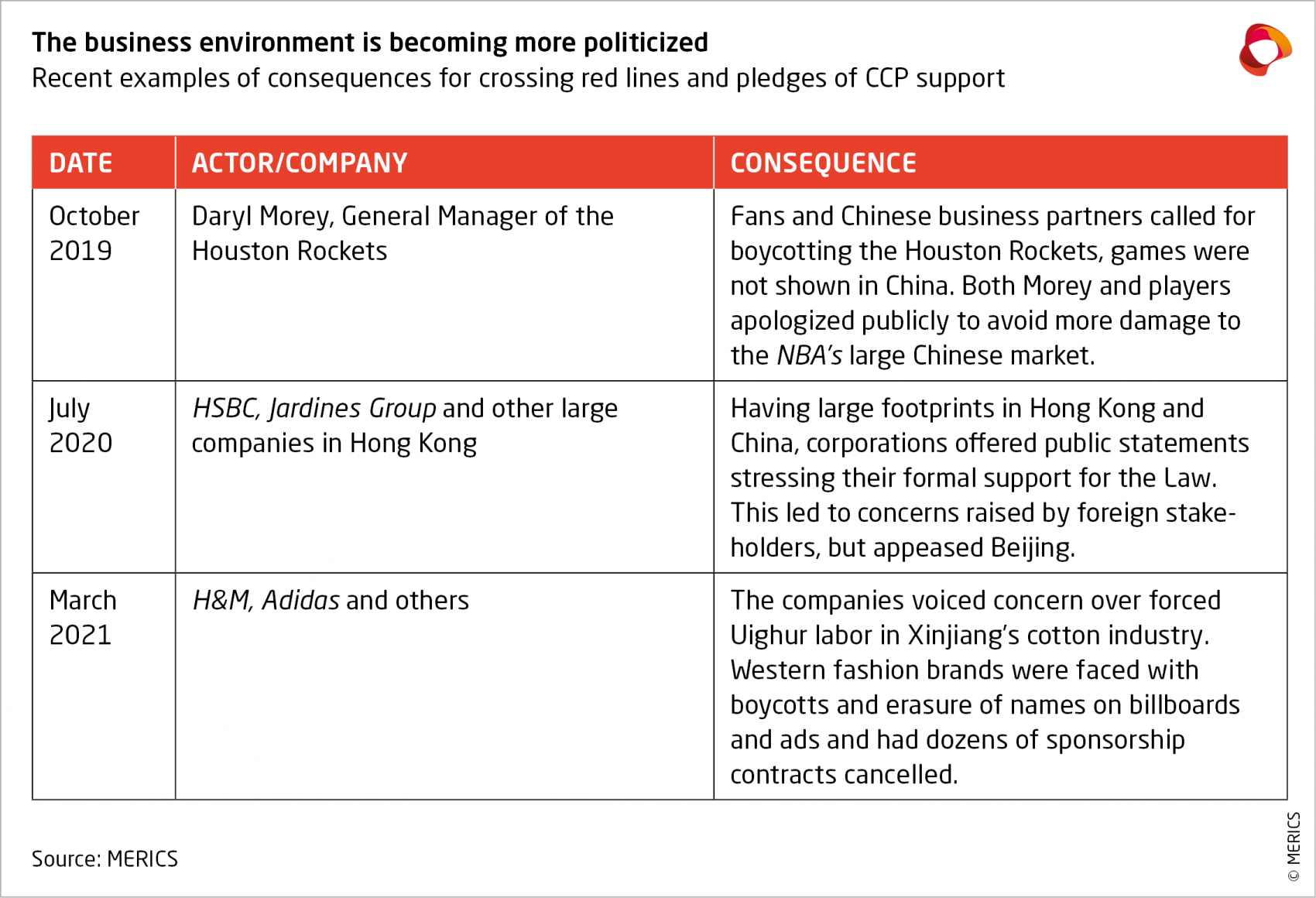

Research shows that the use of ideological mobilization to engender support for the party state in social issues can be as effective as coercive methods.36 Stirring nationalism and patriotism to stimulate political support is a common strategy in China. Foreign companies, for one, now need to be increasingly careful about Beijing’s patriotic sensitivities and dozens of them – from Audi to the NBA – have been forced to apologize for “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” in some way or another.37

The Chinese leadership’s attitude towards private companies is based on the idea of an organic relationship between party, state, and society. Companies should see themselves as “corporate citizens” and with this “citizenship” come benefits – and duties: Don’t only ask how to get rich, ask how to contribute to the national project of development. For most companies this means little more than ideological window dressing, but for strategically important ones, and for those popping up on government radars because of political reasons, it is an increasingly big issue.

Industry-leading companies and private firms seen as important have felt how recent efforts to improve China’s regulatory regimes – in areas like anti-monopoly rules and fintech – also had a political dimension. The party state’s treatment of Ant Group was driven by important and arguably much-needed improvements in industry regulation but came coupled with the demand for a pledge of allegiance. This highlights how industry regulation and political control are two sides of one coin: trimming Ant to prevent it from becoming a black swan by increasing political oversight, and by introducing better fintech industry and anti-monopoly regulation that serve social and economic purposes (see exhibit 4).

The CCP is deepening its organizational integration with businesses through party cells, is co-opting business elites and strengthening its regulatory capacity. The biggest efforts to influence corporate control yet remain limited to firms of certain size or impact. But the balance between control and performance has clearly shifted, and under Xi Jinping mobilizing the CCP apparatus is used increasingly as “organizational weapon” for asserting more control over social organization at large.38 Technological innovation and entrepreneurs willing to take risks are hampered by an outdated and cumbersome bureaucracy – as a disgruntled Jack Ma pointed out in his 2020 speech that angered regulators.39

China’s current direction of travel is clearly towards a business environment in which CCP leadership and norms point the way, powerful state agencies apply tougher regulation and leading private enterprises are expected to pledge their support for political objectives – or at the very least don’t openly resist the party line.

3. Beijing sees the party state ascendant over the liberal state

China’s leadership sees the ability of party-state capitalism to steer economic development and technological modernization as a distinct systemic advantage over free market capitalism. Decades of economic growth, broad provision of public goods and stability have cemented China’s belief in its governance model. Recent months and years have proven its ability to withstand systemic shocks.

Beijing believes in its mix of risk-preventing regulation, state-guided development planning, and an all-of society mobilization towards the CCP-led national project of China’s revival as global power. The 20th CCP Congress in 2022 will most likely see the ascent of Xi to even more power, and with that deepen the organic integration of the economy under politics.

Politically determined targets for development, state-led investment, state-owned equity ties into the private sector, industrial policy and guidance funds will not go away. On the contrary, leaders are calling for an all-of economy effort to “break the US tech blockade”.40 State support will remain an important part of this effort, as highlighted again in the 14th Five-Year Plan. With improved investment screenings and policy learning from the numerous experiences with finds, this way of economic mobilization will generate competitive Chinese players in emerging industries in the coming decade.

Institutionalizing party organizations in corporate governance structures is intended to establish a guiding mechanism to make sure private companies stay in line with national interests. Private companies are currently under no legal obligation to comply with party rules, but recent CCP regulation shows the party is keen to increase its political leverage over all economic actors. On top of formal rules, ideologically-driven messaging is creating a deeply politicized business environment.

The complex relationships between China’s private companies and state enterprises means foreign governments and non-Chinese companies will increasingly be confronted with tensions over security, technology and market access when interacting with Chinese partners. With more party state involvement in the economy, potential interfaces with public actors and political sensitivities will increase also in commercial dealings. Foreign enterprises operating in China will also have to make sure they are not seen as harming party-state interests – and make sure they are seen as contributing to China’s economic and social development (see exhibit 5).

These developments strongly suggest that the “level playing-field” that foreign companies want for doing business in China is not in sight. On the contrary, systemic differences will become an ever-greater challenge. Beijing’s vision for China’s political economic order is blurring the lines between public and private ownership and drawing new priorities for global integration. The dual circulation concept is not about decoupling China or severing cooperation and trade, but about upgrading China’s place in the value chain, being more self-reliant in essential resources and core technologies.

There are, of course, also limitations to the degree the leadership can push ideology into the daily management concerns of companies. The CCP is still no monolithic all-encompassing power, and Beijing’s political strategies have always been met with local tactics to shirk policy viewed as unreasonable or overreaching. Most companies operate freely by following the law without proactively engaging in political activities.

However, the trends discussed in this paper should be seen as coordinated effort to improve alignment with and compliance to central policy. Codifying party rules as state laws and pushing party organizations in firms is advancing the party-state model of combining regulation with supervision, to enable both better regulatory and political-disciplinary line-of sight into the economy. Often this is not about daily management, but about the potential to steer strategic decisions.

How deep political entrenchment in the economy will go is unclear, but few things look likely to alter the current trajectory. Party-state capitalism strives for political stability and control over macro-economic developments – and has so far done so with a sufficient level of economic performance. It accepts inefficiency as the price for control. Unanswered questions about its sustainability are many. But the reality is that China’s leaders believe in the resilience and advantages of their model, and the new development concept is meant to double down on its strengths and increase China’s political-economic resilience and adaptiveness.

Xi and his colleagues have been humble – and realistic – enough to publicly acknowledge “challenges unseen in a century” ahead – like inequality, to mention but one. But they look back at China’s last four decades and see an economic model that is constantly adapting and getting better at overcoming shocks and crises.

However, the challenges China faces today are new and complex in nature, and Beijing’s recipe to tackle them puts preventing economic risks, safeguarding political stability, and national security first. In its systemic competition with liberal capitalism, Beijing sees China’s party-led state capitalist system winning. It is convinced that its political control, flexible economic governance, readiness to incur economic losses for the sake of social and political stability, and technological breakthroughs will eventually lead it to superpower status.

- Endnotes

-

1 | New York Times (2018). "Xi Jinping Thought Explained: A New Ideology for a New Era." February 26. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/26/world/asia/xi-jinping-thought-explained-a-new-ideology-for-a-new-era.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

2 | Xi, Jinping (2021). 把握新发展阶段,贯彻新发展理念,构建新发展格局 (Grasp the new development stage, implement a new development concept, construct a new development pattern). Qiushi, April 29. http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2021-04/30/c_1127390013.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

3 | Pearson, Rithmire, and Tsai (2020). “Party-State Capitalism in China”. HBS Working Paper 21-065.

4 | Blanchette, Jude (2020). “From “China Inc.” to “CCP Inc.”: A New Paradigm for Chinese State Capitalism”. China Leadership Monitor.

5 | Naughton, Barry (2019). “Grand Steerage: The Temptation of the Plan”. in: Thomas Fingar and Jean Oi, eds. China: Choices and Challenges. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

6 | Liu, He (2014). „Overcoming the Great Recession: Lessons from China”. M-RCGB Associate Working Paper Series No. 33.

7 | Crossley, Gabriel (2020). “China expands state jobs for graduates as coronavirus hits private sector.” Reuters. July 27. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-jobs-graduates-idUSKCN24R0UQ. Accessed: May 21, 2021.; Renmin Ribao (2020) “企业“国家队” 抗疫勇担当” (“The corporate “national team” bravely takes upon the fight against the epidemic”). February 19. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/19/content_5480728.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

8 | CCP-Net (2020). ”习近平主持召开中央全面深化改革委员会第十六次会议强调 全面贯彻党的十九届五中全会精神 推动改革和发展深度融合高效联动 李克强王沪宁韩正出席” (”Xi Jinping presides over the 16th meeting of the Central Committee for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, stressing the comprehensive implementation of the spirit of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th CPC Central Committee to promote the deep integration and efficient linkage of reform and development. Li Keqiang, Wang Huning and Han Zheng attended”). November 2. http://www.12371.cn/2020/11/02/ARTI1604319222417265.shtml. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

9 | Xi, Jinping (2016). “习近平:理直气壮做强做优做大国有企业” (“Xi Jinping: self-confidently make SOEs better and larger”). Xinhua. July 4. http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2016-07/04/c_1119162333.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

10 | SASAC (2020). “郝鹏接受中央主流媒体采访 谈当前中央企业发展态势” (“Central media interview of Hao Peng on the current development and situation of central enterprises”). August 11. http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n2588020/n2877938/n2879597/n2879599/c15343606/content.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

11 | Bateson, Andrew (2020). “The State Never Retreats”. Gavekal Dragonomics.

12 | Rosen, Leutert, and Guo (2018). “Missing Link: Corporate Governance in China’s State Sector”. Asia Society.

13 | Central CCP Committee General Office (2015). 中共中央办公厅印发《关于在深化国有企业改革中坚持党的领导加强党的建设的若干意见》 (The General Office of the CPC Central Committee issues 《Several Opinions on Deepening Reform, Adhering to Party Leadership and Strengthening Party Construction in State-owned Enterprises》). August 20. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-09/20/content_2935714.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

14 | Central CCP Committee (2020). 中共中央印发《中国共产党国有企业基层组织工作条例(试行)》 (Central CCP Committee issues 《Regulations for the work of CCP grassroots organizations in SOEs (trial)》). January 5. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-01/05/content_5466687.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

15 | Luong et al. (2021). “Understanding Chinese Government Guidance Funds”, Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

16 | Lardy, Nicholas (2019) The State Strikes Back – The End of Economic Reform in China?. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

17 | Dai, Sarah (2019). “China completes second round of US$29 billion Big Fund aimed at investing in domestic chip industry”. South China Morning Post, July 26. https://www.scmp.com/tech/science-research/article/3020172/china-said-complete-second-round-us29-billion-fund-will. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

18 | Luong et al. (2021).

19 | Feng, Emily (2021). “A Cautionary Tale For China's Ambitious Chipmakers”. NPR, March 25. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/25/980305760/a-cautionary-tale-for-chinas-ambitious-chipmakers. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

20 | Naughton (2020). The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy 1978 – 2020. available on: https://dusselpeters.com/CECHIMEX/Naughton2021_Industrial_Policy_in_China_CECHIMEX.pdf.

21 | Chen and Rithmire (2020). „The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy”. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-020-09308-3.

22 | Wei, Lingling (2021) “China blocked Jack Ma’s Ant IPO after investigation revealed likely beneficiaries”. Wall Street Journal, February 16. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-blocked-jack-mas-ant-ipo-after-an-investigation-revealed-who-stood-to-gain-11613491292. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

23 | Reuters (2021). “Analysis: Chinese retail banks gain customer lending clout as fintechs fall out of favor”. January 28. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-finance-loans-internet-analysis-idUSKBN29W2ZT. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

24 | Guo, Yingzhe (2020). “Fintech Giants Could Pose ‘New Systemic Risks,’ Warns Banking Watchdog Chief”. Caixin, December 8. https://www.caixinglobal.com/2020-12-08/fintech-giants-could-pose-new-systemic-risks-warns-banking-watchdog-chief-101637128.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

25 | Grünberg, Nis and Brussee, Vincent (2021). China’s 14th Five-Year Plan – strengthening the domestic base to become a superpower. Available on:

https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/chinas-14th-five-year-plan-strengthening-domestic-base-become-superpower. Accessed: May 21, 2021.26 | Bai, Chon-En et al. (2020) Special deals for Special investors: The Rise of State-Connected Private Owners in China, available on: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28170. Accessed 14.4.2021.

27 | Grünberg, Nis (2021) Who is the CCP? China’s Communist Party in infographics. Available on: https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/who-ccp-chinas-communist-party-infographics. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

28 | Livingston, Scott (2021). “The New Challenge of Communist Corporate Governance”. Available on: https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-challenge-communist-corporate-governance. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

29 | People’s Net (2018). 《中国共产党支部工作条例(试行)》 (Regulations for the work of CCP branches). November 26.

http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2018/1126/c1001-30420219.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.30 | Horwitz, Josh (2019). „China to send state officials to 100 private firms including Alibaba”. Reuters, September 23. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-alibaba-china-party-idUSKBN1W80DO. Accessed: May 21, 2021.; Sina (2019). “杭州抽调干部进驻阿里等民企 浙江媒体回应争议” (“Hangzhou transfers cadres to Alibaba and other private firms, Zhejiang media react with controverse debate”). Beijing Youth, August 22. https://finance.sina.com.cn/china/gncj/2019-09-22/doc-iicezzrq7690983.shtml. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

31 | Xinhuanet (2020). “干部进驻企业 解决发展难题” (“Cadres dispatched to enterprises solve development difficulties”). Chongqing Daily, November 2020. http://www.cq.xinhuanet.com/2020-11/09/c_1126715210.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

32 | Xinhua (2020). 中共中央办公厅印发《关于加强新时代民营经济统战工作的意见》 (Central CCP Committee General Office issues 《Opinions on Strengthening United Front Work in the Private Economy in the New Era》). August 15. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-09/15/content_5543685.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

33 | Ye, Qing (2020). “叶青:推动党的领导制度体系与民企治理体系有机融合” (“Ye Qing: Promoting an organic integration of the Party's leadership system and the governance system of private enterprises”). ACFIC, September 17. http://www.acfic.org.cn/ldzc_311/jzhld/yq/yqgzhd/202009/t20200917_245057.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

34 | Chen, Yixin (2021). “陈一新:推动政法工作高质量发展,今年“十大重点”是主攻方向“ (“Chen Yixin: Promote a high quality development of political work”, This year the „10 key points“ define the direction of attack“). China Peace, February 2. http://www.chinapeace.gov.cn/chinapeace/c100007/2021-02/02/content_12446483.shtml. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

35 | Xi, Jinping (2020). “(受权发布)习近平:在企业家座谈会上的讲话” (“Authorized release: Xi Jinping’s speech at the Entrepreneur Symposium”). Xinhua, July 21. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-07/21/c_1126267575.htm. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

36 | Mattingly, Daniel (2020). The Art of Political Control in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

37| Chen and Rithmire (2020)

38 | Li, Ling. (2020). “The "Organisational Weapon" of the Chinese Communist Party China's - disciplinary regime from Mao to Xi Jinping”. In: Law and the Party in China: Ideology and Organisation. R. Creemers and S. Trevaskes, Cambridge University Press.

39 | Xu, Kevin (2020). ”Jack Ma’s Bund Finance Summit Speech”. Interconnected, November 9. https://interconnected.blog/jack-ma-bund-finance-summit-speech/. Accessed: May 21, 2021.

40 | Lu, Zhenhua (2021). „Party calls on provate sector to break U.S. tech blockade“. Caixin, January 25. https://www.caixinglobal.com/2021-01-25/party-calls-on-private-sector-to-break-us-tech-blockade-101655472.html. Accessed: May 21, 2021.