China relies on “little giants” and foreign partners to plug stubborn technology gaps

Efforts to upgrade the manufacturing sector have produced patchy results, says Alexander Brown. Beijing hopes drawing on Germany’s Mittelstand model will deliver more success.

Struggling to develop indigenous high-tech suppliers, China is taking a leaf out of Germany’s economic handbook. So-called little giants – highly specialized companies that dominate niche markets – are meant to emulate Germany’s “hidden champions” and develop the core technologies China is lacking. But whether the country can actually engineer such specialized firms remains uncertain. China could find cooperating with foreign companies and institutions on research and development (R&D) more effective – as long as it can attract willing partners.

Patchy results

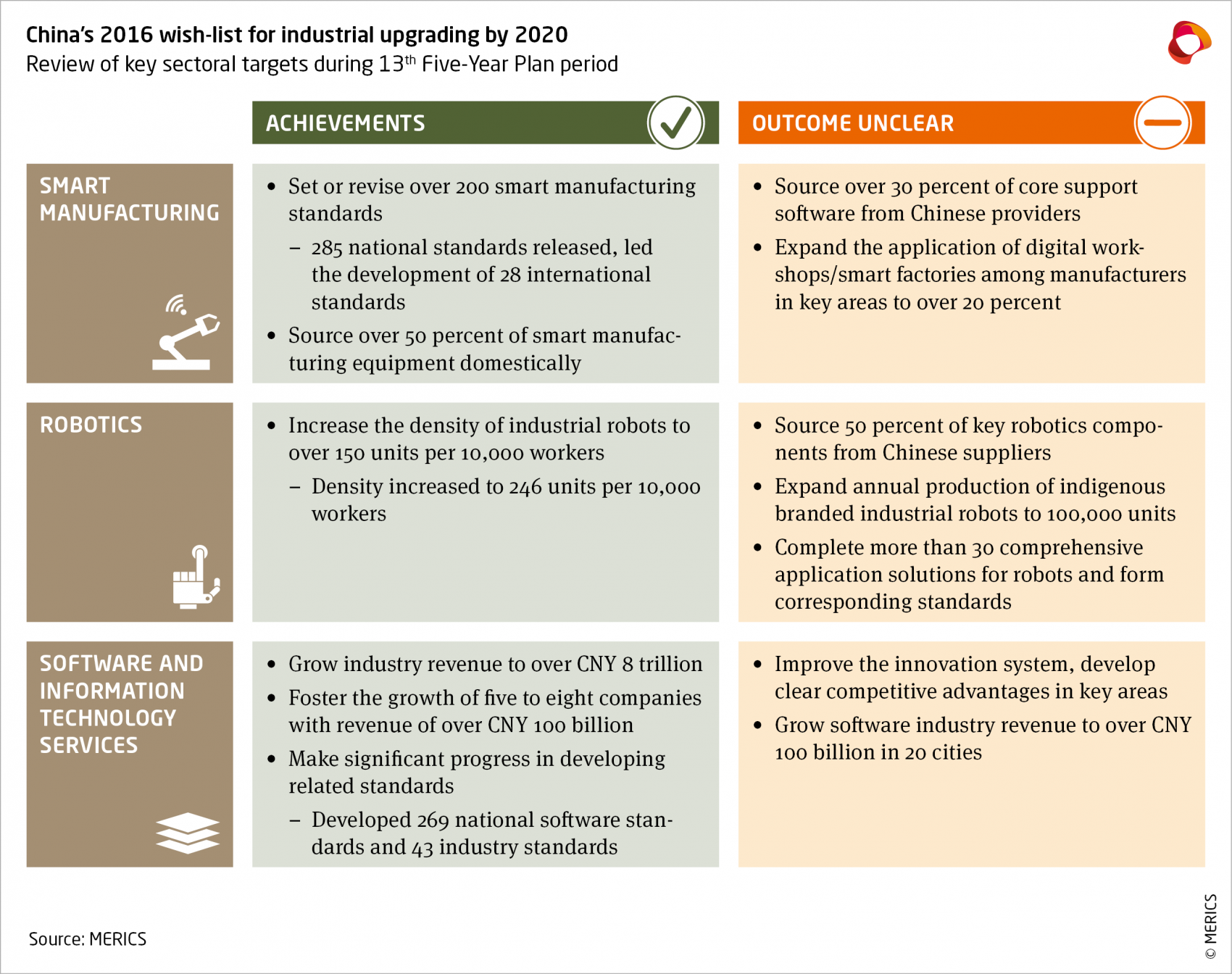

The country’s efforts to upgrade its manufacturing sector have so far produced patchy results (see table). Recent plans focusing on the development of smart manufacturing, robotics and software until 2025 show that these industries are growing rapidly. But they also show that Chinese firms are making little headway with core components and high-end technology, areas in which foreign firms still dominate. The industries covered in the plans are central to the Made in China 2025 strategy and are meant to drive industrial upgrading. But judging by the goals it set itself, China scores no better than a C on its interim report card.

China has performed well in areas like standard setting and increasing domestic production capacity. It now sources 50 percent of smart-manufacturing equipment domestically, for example, and its robot density had by 2020 risen to 246 units per 10,000 workers, pushing its global ranking up from 25th to ninth place in the space of five years. But officials have conspicuously refrained from clarifying China’s progress in other areas by withholding data about things like the share of smart-manufacturing software sourced domestically, the output of Chinese branded robots and domestic capabilities in core robotics components.

Industry data suggests that China’s rapid rollout of smart-manufacturing technology has not made local suppliers more competitive. The production of industrial robots in China has skyrocketed, but the domestic market share of indigenous brands has been steady at about one quarter for the past eight years. This is because most foundational technologies and core components are still beyond China’s reach. Local companies have developed alternatives to less advanced products, but lag behind foreign rivals when it comes to the most advanced offerings in smart manufacturing equipment, industrial software and operating systems.

This challenge to China’s industrial upgrading effort seems to have led policymakers to partly reset their expectations for 2025. In contrast to their 2016 wish-list for 2020, they set no concrete targets for the number of industrial robots produced by indigenous brands, or for the share of key components sourced from indigenous brands. But such adjustments do not mean an end to China’s broader goals. Beijing’s efforts to develop homegrown alternatives will continue, with the added help of little giants and international cooperation.

Little giants

Nurturing German-style Mittelstand champions is meant to fast-track the growth of promising small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to develop core technologies. The government selects little giants based on their financial performance, R&D investment, intellectual property and strategic fit. Apart from prestige, the companies gain access to subsidies, tax cuts, grants and talent. Crucially, the designation signals that the firm has government backing, which should spur investor interest. This is an important factor given the government crackdown which has hit some of China’s major tech companies like Alibaba and Tencent.

The central government has committed CNY 10 billion to foster the growth of 10,000 little giants by 2025. Already 4762 companies have earned the designation and they appear to be the right kind of SMEs. More than half invest over CNY 10 million in R&D annually and over 60 percent are focused on core industrial components, materials, processes or technologies. But that is still no guarantee that they will be able to catch up to existing firms with cutting-edge technology. Most will lack the scale, experience and customer relationships to compete. Moreover, as the ranks of the little giants grow, the share of bad investments will rise.

International cooperation

This suggests China’s most effective pathway to acquiring technology will be cooperating with foreign partners. The country’s recent plans stress the need to attract more foreign firms to invest in R&D and training centers in China, and to deepen international cooperation on standards development. Direct acquisitions of high-tech firms are now more difficult given the tightening of investment screening regimes in Europe and the US. But China could still realize major technology gains by convincing foreign companies to continue R&D partnerships with local firms. Ideally, it would like to see its own little giants teaming up with those abroad.

This makes Germany a valued partner. China is eager to emulate its strengths in advanced manufacturing. Recent examples of cooperation in the machinery and software fields include heavyweights like SAP, Bosch and the Fraunhofer applied research organization, but also Festo Didactic, SICK and other hidden champions. Foreign companies can leverage China’s need for technology to benefit from its innovation system, preferential policies and the chance to realize other projects. This can drive innovation, but in some cases may also help China to replace foreign firms. Finding the right balance between engagement and separation is key.