Ten ways for think tanks to become incubators for policy innovation

by Roderick Kefferpütz

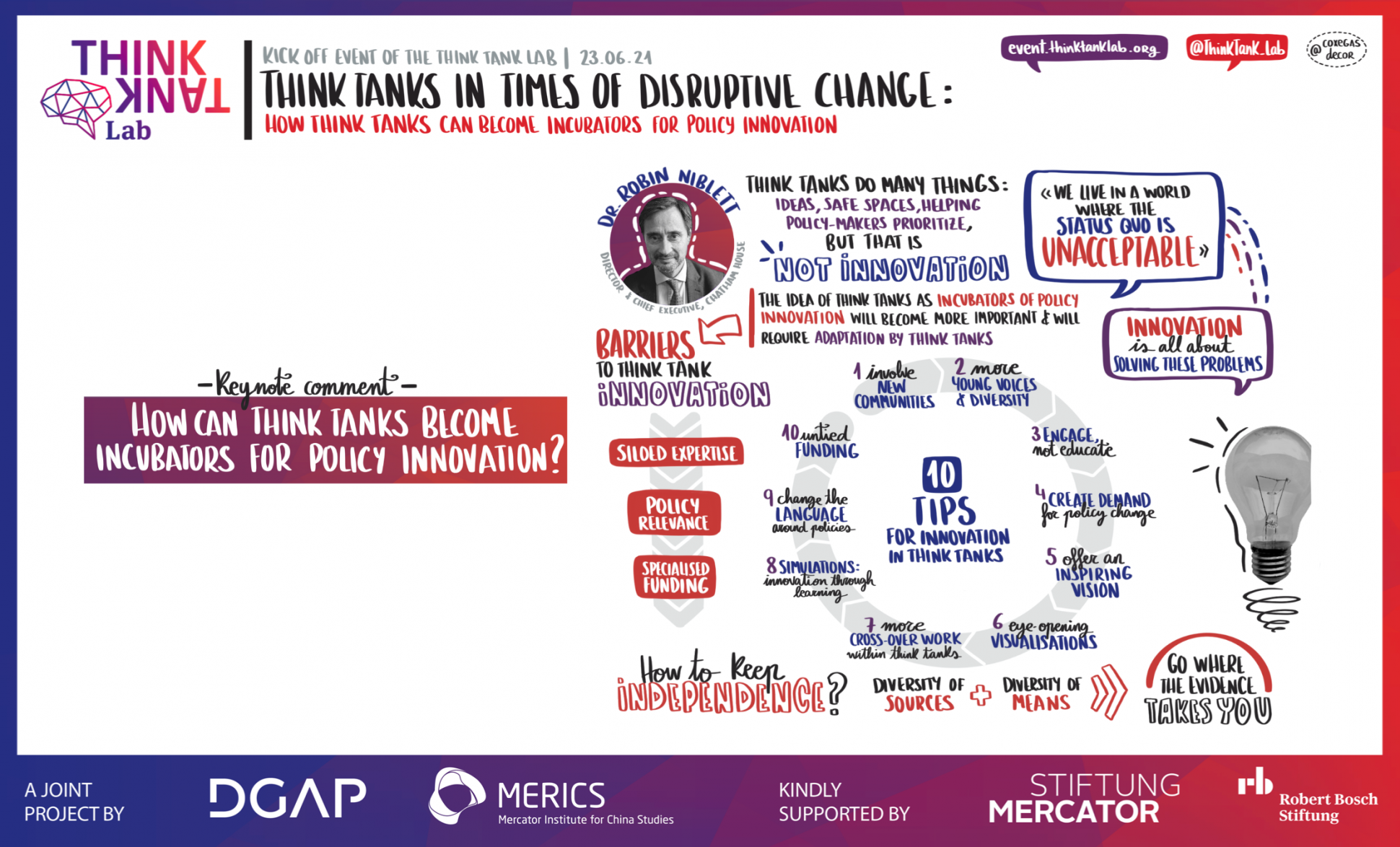

Think tanks have always been sources of information and analysis. But faced with today’s challenges, this role alone is insufficient. Think tanks need to evolve and become incubators for policy innovation. What stands in the way of policy innovation? And how can think tanks overcome these obstacles? These were some of the questions we asked Dr. Robin Niblett, Director of Chatham House. In this article, we set out his 10-point plan on how think tanks can become policy incubators.

Please note: This article is a summary of the keynote speech given by Dr. Robin Niblett at the Think Tank Lab’s kick-off event on June 23, 2021. You can find more information about this event and watch a video of the speech being given here.

From policy prioritization to policy innovation

Traditionally, think tanks are organizations which convene, provide room for semi-confidential debates, and offer political analysis. They inform policymakers and help them to make choices. A lot of the time, policymakers don’t need to be told what to do, but rather what to focus on. But this is policy prioritization, not policy innovation.

Shifting from one to the other will become increasingly important and will require think tanks to change their ways of working.

After all, innovation isn’t just coming up with a novel idea – it is not the same as invention. Think tanks are certainly used to coming up with new ideas for policymakers that compete with other ideas. But innovation is about coming up with new ideas which are implemented. Innovation is all about getting things done and solving the problem at hand.

Innovative ideas tend to be drawn from new connections. Increasingly, therefore, think tanks will have to provide a space for a wide range of stakeholders to come together and come up with new ways of policymaking. Achieving that change will require ten steps.

Why think tanks have difficulties innovating

Think tanks will have to overcome three obstacles if they are to innovate:

- Siloed expertise: Think tanks are homes for experts. We have people with PhDs who specialize and look into the nitty-gritty details of every issue. But the problem is that expertise tends to be rather specialist. And this creates barriers and issue bubbles, which think tank structures often mirror. This is the exact opposite of what enables innovation. Big, comprehensive challenges like climate change and inequality require comprehensive answers beyond the silos.

- Policy relevance: It sounds contradictory but being policy-relevant can be an obstacle to innovation. Many think tanks in the US, for example, are so well-connected with the policy world and know policy so well, that they formulate their ideas within the existing policy frameworks. It makes them unable to come up with original ideas when it comes to policies or new ways to implement them.

- Inflexible funding: Innovation needs flexible funding. However, funding has become increasingly specialized. It is tied to specific projects and particular deliverables. This makes it difficult for think tanks to innovate, because they are forced to continuously pursue the demands of funders. Therefore, for think tanks to innovate, funders will have to adjust their work as well, focusing not only on short-term output but also providing space for the long term that allows for the adjustment of research agendas to new developments.

Ten ways for think tanks to become policy innovators

So how can think tanks overcome these challenges? There isn’t a silver bullet, but the following ten points can be waymarkers towards greater policy innovation by think tanks.

- Involve wider communities. It is no longer enough to only engage with government, business, and organized civil society. Think tanks need to expand their reach and involve artists, design companies, technologists, and psychologists; people that are rethinking how to do things.

- Include more young voices. Every think tank has its panel of senior advisors – but senior advisers give views and perspectives based on their experience, which is important and useful but might not reflect the thinking of younger generations. To deal with this, Chatham House set up a panel of young advisers, that is diverse and has a good gender balance. Bringing both panels together brings a multitude of views and perspectives. Inclusivity is incredibly important to advance innovation.

- Engage new communities. A lot of communities that are currently not part of the policy debate deserve a seat at the table. Think tanks can be allies in the struggle for a more inclusive political debate. Instead of telling others what should be done, think tanks – as convenors – can make sure that underrepresented communities are included in debates that affect their future.

- Create demand for policy change. Influencing policy isn’t just about getting analyses to important decisionmakers, it is about advancing implementation and political change. Decisionmakers won’t take decisions if they don’t have the sense that the idea already has some public resonance. So, think tanks also have to be involved in creating resonance.

- Offer an inspiring vision. It’s not just about knowing how policy works, it is also about engaging people around a vision. Chatham House has done a project looking at how Piccadilly Circus – one of London’s major road junctions and public squares – could look like in 30 to 50 years’ time. They gathered people of diverse backgrounds, who came up with a vision for Piccadilly Circus. Visions are part of innovation: They show us where we could go and then it’s up to us to develop the necessary measures to get there.

- Eye-opening visuals. Visuals can certainly be over-used and do not always create sufficient impact, but visualizations can have an incredible impact by capturing a dimension of a policy problem in shocking clarity and galvanizing policy action.

- Less programmatic expertise, more cross-over work. Think tanks need to break open their own silos and look at policy issues from a variety of perspectives, bringing different policy areas together. The New America Foundation, for example, was founded in this spirit. They saw themselves as an “anti-think tank.” They didn’t want to have any specialists, but people who could think across the board.

- Simulate it. Learning is an incredible tool for innovation. And in this context, tabletop exercises and simulations are an amazing way for people to come up with breakthrough ideas and innovate.

- Watch the language. It isn’t always about changing the policy. Sometimes changing the terms and language around which a policy is designed can have an incredible impact. Coming up with definitions is basic policymaking, but using language that is inclusive and brings together different actors can also lead to progress.

- Last but not least: Funding. It is very difficult to innovate if your funding is tied to particular projects and specific deliverables. Innovation needs flexible funding.

This isn’t an exhaustive list and some of these points are already well-known, but these are elements, highlighted by Dr. Niblett, that can help think tanks in further developing their work and increasing the potential for policy innovation.

Roderick Kefferpütz

Senior Analyst at MERICS

Roderick Kefferpütz is a Senior Analyst at MERICS focusing on Germany’s China policy, Sino-Russian relations and China’s role in a changing global order. He heads the MERICS Lab, which generates new ideas for innovative think-tank work through exchanges with MERICS experts and external partners. Before joining MERICS, Kefferpütz was Deputy Head of Unit for Strategy at the State Ministry of Baden-Württemberg. Prior to that he worked ten years in Brussels, amongst others as chief of staff to MEP Reinhard Bütikofer, Chair of the European Parliament’s Delegation to China. Kefferpütz began his professional career with research positions at the Heinrich Böll Foundation offices in Moscow, Warsaw, and Brussels.