Decoding Chinese concepts for the global order

How Chinese scholars rethink and shape foreign policy ideas

Main findings and conclusions

- Chinese leaders leave no doubt about their ambitions to shape the world order, but there is limited understanding of what this entails. Beijing’s vision for a new world order remains blurry. The vagueness of official jargon makes it difficult to grasp the implications of official terms such as the “community of shared destiny for mankind,” “a new type of international relations” or “win-win cooperation.”

- For international counterparts it is becoming an urgent exercise to grasp the sources, dynamics and implications of Chinese “world-making.” Chinese thinking on world order informs China’s current foreign policy practice and it offers a glimpse into a potential future world order in which China has assumed a greater leadership role. It also underpins strategic “concept export” efforts by Chinese party-state authorities.

- Trends in debates among Chinese academics offer a limited window into how the CCP leadership sees a (future) world order. First, Chinese scholars’ thinking has taken a “counter-universalistic” turn, questioning key Western assumptions and concepts. Second, by focusing on relationships, Chinese scholars develop a fundamentally different take on global integration that often conflicts with sovereignty or the concept of equal nation states. Finally, prominent Chinese scholars increasingly view China’s regional or global leadership as a given and discuss which ideals should guide China’s new role in international affairs.

- European policymakers and experts need to be better prepared for educated dialogue and confrontation in engaging with Chinese attempts at rethinking world order. European counterparts have to catch up to understand distinct Chinese elite world views and pierce through partially unique concepts they use to describe world affairs. European governments and research institutions need to devise proactive strategies to engage Chinese thinking and thinkers in the search for commonalities. And they have to defend European normative and intellectual foundations where necessary.

1. Chinese concepts for shaping the world order are insufficiently understood

“What does China think?”,1 “What does China want?”,2 and “How does Xi Jinping see the world?”,3 are questions that puzzle anyone interested in world politics or China’s global role. One thing has become obvious: Chinese leaders leave no doubt that they want to shape the future world order. At the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary and State President Xi Jinping, spelled out his vision to transform China into a global power “moving closer to center stage” in unprecedented clarity.4 Chinese leaders’ ambitions are also becoming more visible as CCP organs and government officials vigorously promote what they call Chinese visions, concepts and solutions internationally.

Chinese thinking on world order matters. Examining it helps uncover the motivations behind China’s foreign policy and provides clues on how and why Beijing seeks to shape world politics. While only some of the ideas currently under discussion might materialize, paying close attention to Chinese thinking is a necessary exercise to anticipate what a world order on Chinese terms might look like. Discussions among Chinese scholars also help uncover the roots and implications of the concepts Chinese authorities promote internationally.

But Beijing’s vision for a new world order remains blurry. The much promoted “community of shared destiny for mankind” (人类命运共同体) is a case in point: The concept has permeated China’s foreign policy rhetoric since 2013. State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in an attempt to clarify official foreign policy jargon, described the “community of shared destiny for mankind” as the “goal” (目标) of Chinese diplomacy without specifying what this might entail, or how Beijing intends to attain this goal.5 Interpretations offered by Chinese officials leave international observers guessing or even irritated by what often seems to be simply an international expansion of domestic propaganda.

2. Academic debates offer a window into CCP thinking

Piercing through the vagueness of official Chinese jargon remains difficult. Whereas the most important debates on China’s role in the world take place behind closed doors within party circles and the Chinese strategic community, a few high-profile public contributions have provided more substance.

These highly coordinated official statements on China’s global role, however, usually focus on what Beijing does not want. As chairwoman of the National People’s Congress Foreign Affairs Committee Fu Ying argued that China does not subscribe to a US-led world order. She described the current world order as based on US values and military alliances. According to her, this makes it an exclusive concept from which mainly Western countries benefit.6 Senior Colonel Zhou Bo, director of the Security Cooperation Center of China’s Central Military Commission (CMC)’s International Military Cooperation Office, made clear that Chinese leaders are highly discontent with this (US-) alliance-based global system and Asian regional order.7

While not completely aligned with official positions, a few publicly visible Chinese scholars can shed some light on how the Chinese leadership thinks about world order for three reasons:

- The party-state invests substantially in influencing research agendas. Under the control of the CCP, the National Planning Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences administers funding for all social science research including International Relations (IR). The office plays a key role in setting research agendas.8 Combined with the CCP censorship regime that sets clear boundaries for research and publications, at least parts of Chinese scholars’ debates are turned into sounding boards for official policy concepts.

- At times, scholars contribute to the formulation of Beijing’s programmatic visions. Channels for doing this include institutional linkages of think tanks and research institutes, media outreach and personal contacts to Chinese leaders.9 In some instances, (foreign) policy concepts have been directly attributed to scholars: Zheng Bijian, former executive vice president of the Central Committee’s Central Party School, is associated with the idea of China’s “Peaceful Rise” publicized first in 2002.10 Wang Huning, adviser to Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping presumably developed key official concepts associated with their respective reigns: “Three Represents,” “Scientific Outlook on Development” and “China Dream.”11

- Much more difficult to pin down, scholars and officials often share socialization and education experiences that shape their world views and perspective on world politics.

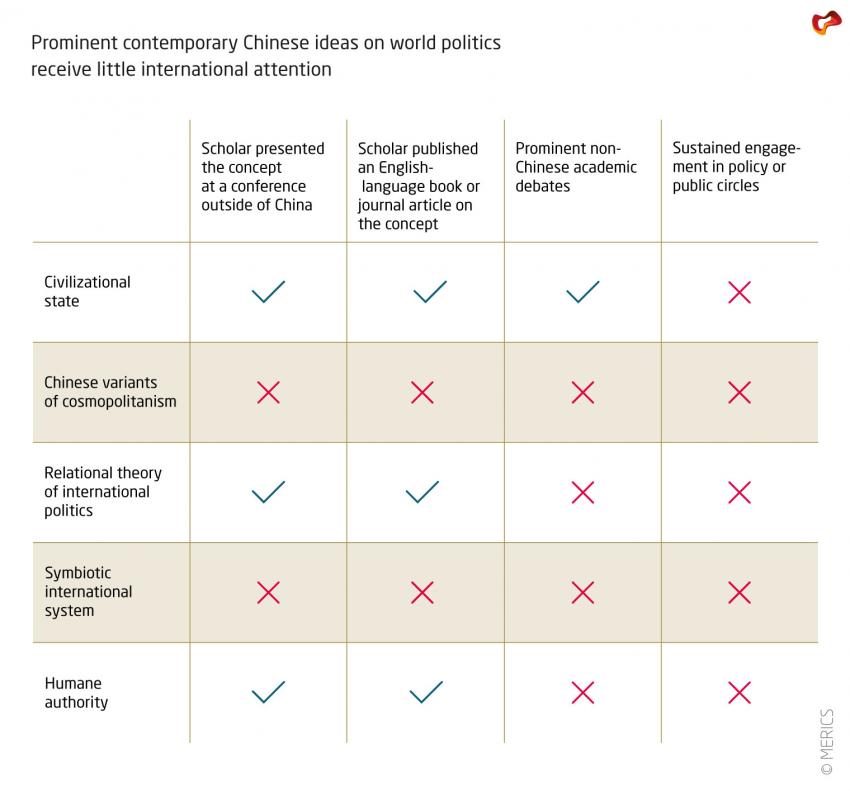

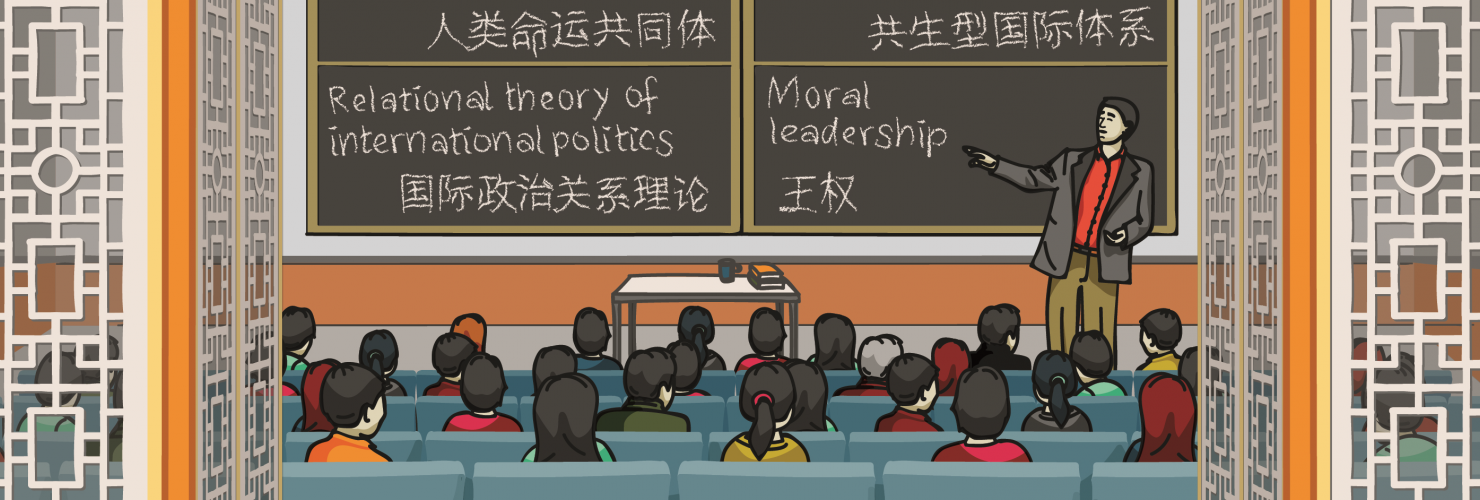

Scholarly debates in China about the features of a future world order have yet to receive broad international attention. Some more mainstream Chinese scholars, including Wang Jisi, Zha Daojiong, Chen Dingding to name only a few, received parts of their training in the West and continue to be engaged internationally.12 To some extent, Chinese international relations scholars will continue to think inside the framework of a global capitalist modernity and post-WW2 international order. More transformative intellectual work and far-reaching concepts such as the one of a “symbiotic international system” or Chinese variants of cosmopolitanism remain confined to Chinese-language debates. While scholars outside of China pay attention to these discussions at least to a limited extent, the wider public in Europe does not (yet) engage with transformative Chinese ideas on world politics (cf. Figure 2).

The following section summarizes key take-aways from an in-depth reading of selected current debates among Chinese scholars.

Selection of material for this analysis: In China’s almost 30 leading academic journals on International Relations (IR),13 scholars discuss alternative forms of world politics extensively. This makes identifying the most compelling ideas challenging. Two criteria have been used to select the articles introduced here: First, the author considered articles published in the ten most important Chinese-language IR journals between 2012 and the first half of 2018. From the tables of contents, she selected the articles with titles suggesting a conceptual discussion of international relations rather than an empirical assessment of China’s foreign policy.14 Second, the author considered recent publications of the ten most prominent theory-focused Chinese IR scholars as identified by their peers.15 The selection of ideas that challenge core tenets of mainstream IR thinking was deliberate. As much as this approach tries to be transparent on how contributions were selected, it is beyond the scope of this report to provide a full account of how Chinese scholars think about the future of the world order.

3. Three key takeaways from current debates among Chinese scholars

3.1. (Counter) universalistic concepts of world politics

The first takeaway concerns the remarkable scope of Chinese scholars’ thinking about world order. Prominent current debates focus on “mankind” and a “re-born cosmopolitanism” as key elements of a future world order. Chinese thinking on world politics is also often presented as a (superior) alternative to “Western” models, with frequent references to seemingly traditional or ancient conceptual underpinnings.

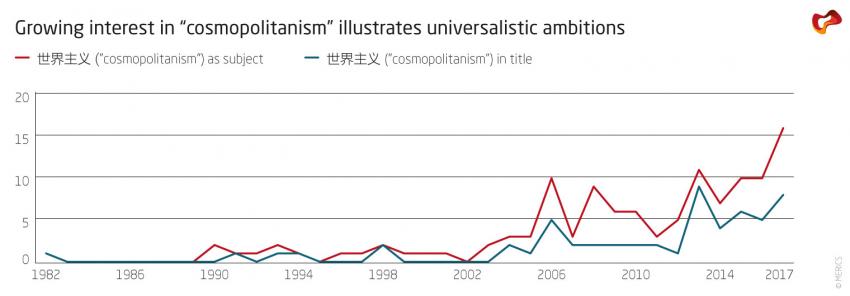

Many Chinese scholars center their thinking about world order on notions of “mankind” (人类) and “cosmopolitanism” (世界主义). Cai Tuo (蔡托), one of China’s most prolific scholars working on globalization and global governance, describes “mankind” as the only relevant actor in international relations.16 Within Chinese debates about world order, there is also a growing interest in “cosmopolitanism” with a very particular “communitarian spin”17 (cf. Figure 3). Chinese scholars working with this approach argue that (the Western idea of) cosmopolitanism needs to be “re-born” in the age of globalization. Most importantly, they call for eliminating the focus on the individual. Promoting a “global cosmopolitanism” based on an all-encompassing notion of “mankind,” they criticize the “old, mainstream” cosmopolitanism because it only focused on the individual’s rights and duties.18

Chinese scholars’ counter-universalistic ambitions also shine through when they present Chinese thinking on world politics as superior to what they label “Western” thinking. Many Chinese IR scholars portray Western scholarship on world politics as part of an outdated and dysfunctional “old world order.”19 They focus on dissecting “the West’s failures” using the 2008 financial crisis, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as US president to argue that the new ideas they propose can “reconstruct the world order” and “solve global governance crises.”20

Current debates often feature references to ancient or traditional notions of order, including “tianxia” (天下), to highlight or legitimize the distinctiveness of contemporary Chinese foreign policy thinking. “Tianxia,” often translated as “all under heaven,” describes a Confucian ideal of a borderless world with China at its center. In her recent MERICS China Monitor Didi Kirsten Tatlow argues that such ancient ideals and practices persist in today’s China and CCP-organized foreign relations.

According to her analysis, China’s imperial court focused on managing relations with those whom it saw as “barbarians,” a concept which included every non-Han ethnicity, in order to keep power safe at home. Today, the CCP is (re-) establishing an “outward expanding system of direct and indirect control aimed at making the world safe for China and, more importantly, the CCP itself.”21

3.2. A notion of global integration without sovereignty and equal nation states

With a strong focus on relationships, several Chinese scholars develop a fundamentally different take on how global integration works. Their understanding of the concept has major implications for China’s foreign policy practice.

Proponents of the “relational theory of international politics” (国际政治关系理论) claim that relations, not actors, determine international politics.22 For Qin Yaqing (秦亚青), one of China’s most prominent IR scholars, international politics are driven by interwoven, dynamic relationships. Two consequences emerge from this proposition: First, an acting entity cannot on its own decide how it conducts its external relations. Instead, the respective circle of relationships an actor is embedded in enables or constrains behavior. Second, since actors do not possess a fixed amount of power but become more powerful if they can use their relations to their advantage, they need to constantly manage their circles of asymmetric relationships to generate power.23

Despite China’s insistence that all states should be treated equally, asymmetric networks play a key role in its foreign policy practice. At first sight, many of the formats China sets up, such as the 16+1 summits with Central and Eastern European countries or the Forum for China-Africa Cooperation, resemble multilateral institutions. However, a closer look shows that these formats resemble China-centered networks. The agenda of their summits leaves ample room for bilateral meetings between Chinese representatives and representatives from other countries. Without a general secretariat, the formats are managed from within China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs with Chinese officials in the lead. This foreign policy approach puts into practice the idea of China-centered relationship management in line with Beijing’s evolving interests.

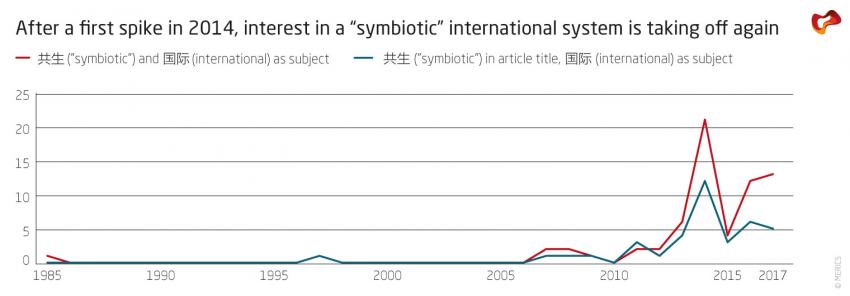

Closely related to this focus on relationships, some scholars assume that actors can only exist in relation to each other. They describe the international system as “symbiotic” (共生), a concept which they take from biology.24 These scholars dismiss the idea that actors can exist independently of each other, which they characterize as the “there is you without me and me without you” antagonism (“有你无我,有我无你” 的对抗式).25 A benign interpretation of this claim is that any state needs to support others in their development to guarantee its own stability,26 but it could also imply that most states other than the most powerful simply need to follow suit. The fact that Chinese scholars link “symbiosis” to China’s great power diplomacy27 and to China’s international responsibility28 suggests that they imagine China as leading this new form of global integration.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the prime example of how a Chinese approach to global integration can look like in practice: BRI’s geographical flexibility echoes the idea of a loosely integrated symbiotic international system without clear boundaries. Without institutionalized procedures, an alignment of interests on Beijing’s terms shall develop through networked bilateralism and China’s gravitational force and coordination mechanisms. In this manner, a series of Memoranda of Understanding on the BRI, for instance, extract commitments by international counterparts that are in line with the Chinese party state’s core interests.

3.3. Two ideals for China's international leadership

Many Chinese scholars today take it as a given that China should lead in world politics. They have moved on to discussing not if or why, but how China should lead. Two ideals for China’s regional and global leadership can be condensed from current academic debates: China as a benevolent leader and as an actor who leads by example.

As a benevolent leader, China is supposed to show concern for others, especially weaker states, and speak for them. The concept “humane authority” (王权) put forward by Yan Xuetong (阎学通), one of China’s most famous IR scholars, captures this ideal. He argues that the dominant state, that is the most powerful state in the international system, should be on good terms with all other countries and respect them. All the benevolent leader’s actions should be guided by morality. For definitions of morality he draws on ancient Chinese philosophers, mainly Xunzi.29

Presenting China as a benevolent and moral actor not only features prominently in China’s foreign policy rhetoric. In the international arena, China has a long tradition of stepping forward as an advocate for the interests of developing countries and as a bridge-builder in international fora such as the G20.

The idea of “leading by example” best captures a second ideal that can be extracted from Chinese scholars’ debates. Chinese experts increasingly argue that international models and solutions can be deduced from China’s development path (and success). Zhang Weiwei (张维为), for example, who claims to have studied China’s development path extensively uses the concept of “civilizational state” to describe China’s particularities and unique advantages.30 In his view, the virtuous combination of civilizational traditions with modern, authoritarian institutions should be a model for others.31

In foreign policy practice, Chinese officials have become much less shy about promoting Chinese concepts to international audiences. Since 2016 the promotion of a “China solution” (中国方案) as a remedy for numerous international problems ranging from “global economic blues”32 to conflicts in the Middle East33 emerged as a strong component of China’s foreign policy rhetoric. Chinese leaders also attempt to leave their mark on international documents through promoting Chinese foreign policy concepts. In March 2017, Chinese party-state media, for example, applauded the Chinese government for managing to insert the “community of shared destiny for mankind” in a UN Security Council Resolution.34 In June 2017, the UN Human Rights Council for the first time adopted a resolution initiated by China. Completely in line with CCP rhetoric, it framed economic development as a precondition for attaining human rights.35

4. Europe needs to prepare for educated dialogue and contestation

It should matter to European policymakers, academics and publics that Chinese elites tend to see the world differently and increasingly expect their voices to be heard. Europeans still have a long way to go in taking both mainstream and more transformative Chinese thinking on world order seriously. To engage with distinct Chinese elite world views, European actors will benefit from better baseline knowledge and sensitivity for nuances in Chinese debates. They also need to operate in an environment where intellectual and normative exchanges with Chinese counterparts are increasingly (perceived as) an element of “systemic competition” between different modes of domestic and global governance.

Initiatives such as the proposal by French President Macron to establish a “European Institute for Sinology” might provide important additional resources to engage with policy relevant intellectual developments in China, if they gather genuine European support. To prepare for educated dialogue and contestation, European government actors, research and exchange institutions need to devise more immediate measures, including the following:

- Cultivating focused exchanges on world politics with emerging Chinese intellectual voices:36 European exchange institutions and foundations active in this field need to devise new regular exchange formats to bring young, talented Chinese experts on international relations and related fields to Europe.

- Consolidating and expanding European efforts to monitor and analyze Chinese academic and think tank debates: Priority topics should include Chinese interpretations of global structural change, the provision of international public goods, multilateralism and international integration, as well as discussions on Chinese leadership. New tools for big data analysis should also be deployed to identify broader trends and patterns in Chinese public thinking on world affairs.

- Teaming up with selected Chinese counterparts who are not fully absorbed by the Chinese party state to make current intellectual efforts to understand global developments mutually accessible: Multilingual cross-publication beyond the world of academic journals could be facilitated by advances in automatized translation. In-depth analyses will depend on more institutionalized frameworks for cooperation including joint initiatives such as the planned Sino-German Merian Center for Advanced Studies.

- Expanding efforts to promote European thinking in China’s policy and elite circles. European foreign policy actors from member states and the EU should offer joint European training courses for Chinese diplomats on priority issues for European diplomacy. EU research funding should prioritize projects that facilitate access of European foreign policy experts to Chinese audiences. Where European actors promote specific principles in relations with China (such as “reciprocity” or “connectivity” on European terms), these conceptual advances demand more intensive intra-EU preparation and coordination.

- Leading targeted discussions with senior Chinese policy makers about core concepts that underpin Chinese visions of world order. Europeans should align efforts and talking points to request clarifications from Chinese counterparts regarding vague visions and terms for instance in consultations between European foreign policy planning units and the CCP International Department.

- Pushing back against attempts by Chinese authorities to insert concepts and interpretations that are not compatible with European interests and standards into international discourse and documents. Where Chinese concepts undermine European normative and intellectual standpoints, European officials and experts need to alert like-minded counterparts, seek alignment and devise timely counter-efforts.

It is high time to engage more proactively and systematically with Chinese intellectual and policy debates about world affairs. This should by no means only be a defensive undertaking geared towards mere understanding and acceptance. European experts and policy makers alike will have to identify diversity in Chinese debates, leverage commonalities and be better prepared to defend diverging normative and intellectual standpoints that underpin European interests.

- Endnotes

-

1 | Mark Leonard, What Does China Think? (Public Affairs, 2008).

2 | Kerry Brown, China’s World : What Does China Want? (I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2017).

3 | Kevin Rudd, “How Xi Jinping Views the World,” Foreign Affairs, May 10, 2018.

4 | Xi Jinping, “Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” Delivered at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China October 18, 2017, 2017.

5 | Wang Yi (王毅), “在习近平总书记外交思想指引下开拓前进 (A Few Explanations of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Thinking on Foreign Policy),” April 11, 2018.

6 | Fu Ying, “Under the Same Roof: China’s View of Global Order,” New Perspectives Quarterly 33, no. 1 (January 2016): 45–50.

7 | Zhou Bo, “The US Is Right That China Has No Allies – Because It Doesn’t Need Them,” South China Morning Post, June 2016.

8 | Heike Holbig, “Shifting Ideologics of Research Funding: The CPC’s National Planning Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43, no. 2 (2014): 13–32.

9 | Pascal Abb, “China’s Foreign Policy Think Tanks: Institutional Evolution and Changing Roles,” Journal of Contemporary China 24, no. 93 (2015): 531–53.

10 | Bonnie S Glaser and Evan S Medeiros, “The Changing Ecology of Foreign Policy Making in China: The Ascension and Demise of the Theory of ‘Peaceful Rise,’” The China Quarterly 190 (2007): 291–310.

11 | Haig Patapan and Yi Wang, “The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China,” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 109 (March 28, 2018).

12 | G. John Ikenberry, Jisi Wang, and Feng Zhu, America, China, and the Struggle for World Order : Ideas, Traditions, Historical Legacies, and Global Visions, n.d.; Jisi Wang, “Thoughts on the Grand Change of World Politics and China’s International Strategiy,” in China and the World: Balance, Imbalance and Rebalance, ed. SHAO Binhong (Brill, 2013), https://doi. org/10.1163/9789004255845; Dingding CHEN and Jianwei WANG, “Lying Low No More? China’s New Thinking on the Tao Guang Yang Hui Strategy,” China: An International Journal 09, no. 02 (September 20, 2011): 195–216, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219747211000136.

13 | In the “China Academic Journals Full-Text Database”, 27 publications are listed as International Relations (国际关系) journals. .

14 | The Beijing University Library regularly publishes a catalogue that lists the most important journals for each field. For International Relations these are 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics), 现代国际关系 (Contemporary International Relations), 国际政治研究 (The Journal of International Studies), 国际观察 (International Review), 外交评论 (Foreign Affairs Review), 当代世界与社会主义 (Contemporary World and Socialism), 国际问题研究 (International Studies), 国际论坛 (International Forum), 当代世界社会主义问题 (Issues of Contemporary World Socialism).

15 | Peter M Kristensen and Ras T Nielsen, “Constructing a Chinese International Relations Theory: A Sociological Approach to Intellectual Innovation,” International Poltical Sociology 7 (2013): 19-40.

16 | Cai Tuo (蔡托), “世界主义的新视角:从个体主义走向全球主义 (New Perspective on Cosmopolitanism: From Individualism to Globalism),” 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics) 09 (2017).

17 | Gao Qiqi (高奇琦), “社群世界主义:全球治理与国家治理互动的分析框架 (Communitarian Cosmopolitanism: An Analytical Framework for the Interaction Between Global Governance and National Governance),” 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics) 11 (2016).

18 | Cai Tuo (蔡托), “世界主义的新视角:从个体主义走向全球主义 (New Perspective on Cosmopolitanism: From Individualism to Globalism).”

19 | Qin Yaqing (秦亚青), “关于世界秩序与全球治理的几点阐释 (Explanations on the World Order and Global Governance),” 东北亚学刊 (Journal of Northeast Asia Studies) 02 (2018).

20 | Guo Shuyong (郭树勇), “新型国际关系:世界秩序重构的中国方案 (New Model of International Relations: The Chinese Path to Recontruct World Order),” 公关世界, 2018.

21 | Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “Cosmological Communism: The Global Chinese State,” MERICS China Monitor, 2018.

22 | Qin Yaqing (秦亚青), “国际政治关系理论的几个假定 (Assumptions for a Relational Theory of World Politics),” 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics) 10 (2016).

23 | Qin Yaqing, “A Relational Theory of World Politics.”

24 | Cai Liang (蔡亮), “共生视角下‘中国责任’的目标、实践及保证,” 国际观察 (International Review), no. 05 (December 20, 2015): 93–103.

25 | Su Changhe (苏长和), “从关系到共生—中国大国外交理论的文化和制度阐释 (From Guanxi Through Gongsheng: A Cultural and Institutional Interpretation of China’s Diplomatic Theory),” 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics) 01 (2016).

26 | Ping Huang, “变迁、结构和话语:从全球治理角度看‘国际社会共生论,’” 国际观察 (International Review), no. 01 (December 8, 2014).

27 | Sun Changhe (苏长和), “从关系到共生——中国大国外交理论的文化和制度阐释 (From Guanxi to Gongsheng: A cultural and systemic Interpretation of China’s Great Power Diplomatic Theory),” 世界经济与政治 (World Economics and Politics), no. 01 (December 8, 2016): 5–25+156.

28 | Cai Liang (蔡亮), “共生视角下‘中国责任’的目标、实践及保证 (The Goal, Practice and Guarantee of „China’s Responsibility“ from the Perspective of Gongsheng),” 国际观察 (International Review) 05, no. 93–103 (2015).

29 | Yan Xuetong (阎学通), “公平正义的价值观与合作共赢的外交原则,” 国际问题研究, December 6, 2013.

30 | Zhang Weiwei (张维为), “我的中国观 ——兼论一个‘文明型国家’ 的崛起,” 思想政治工作研究 02 (2015).

31 | Zhang Weiwei (张维为), “文明型国家”的概念 (Shanghai: 上海人民出版社, 2017).

32 | Xinhua, “Economic Watch: Key Forum to Rally Support for Belt and Road Initiative,” Xinhua Net, April 2017.

33 | Jianing Yao, “Xi’s Fruitful Middle East Tour Highlights China’s Commitment to Building New Type of Int’l Relations,” Xinhua, 2016.

34 | http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-03/20/c_136142216.htm. Accessed: 03/05/2018

35 | http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-06/23/c_136387460.htm. Accessed: 03/05/2018

36 | For a start see: https://thediplomat.com/2016/01/the-10-young-chinese-foreign-policy-scholars-you-should-know/ Accessed: 11/08/2018