The Party does not yet rule over everything

Assessing the state of online plurality in Xi Jinping’s “new era”

Main findings and conclusions

- The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) increased control over Chinese society has resulted in a more limited spectrum of opinions expressed online. Since 2017, the Chinese government has introduced new stipulations to enforce user and content control also in semi-closed discussion forums and private chat groups.

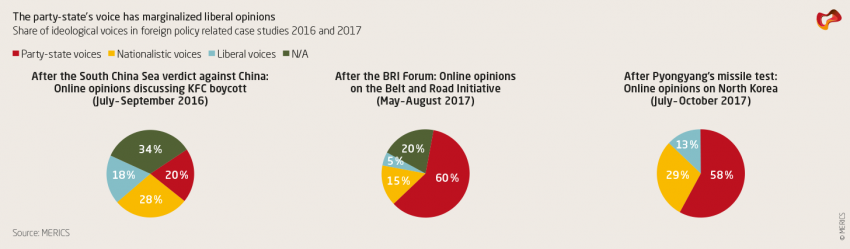

- The CCP has successfully shaped online discussions in two foreign policy areas key to President Xi Jinping’s national as well as international legitimacy, the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) and the North Korea issue.

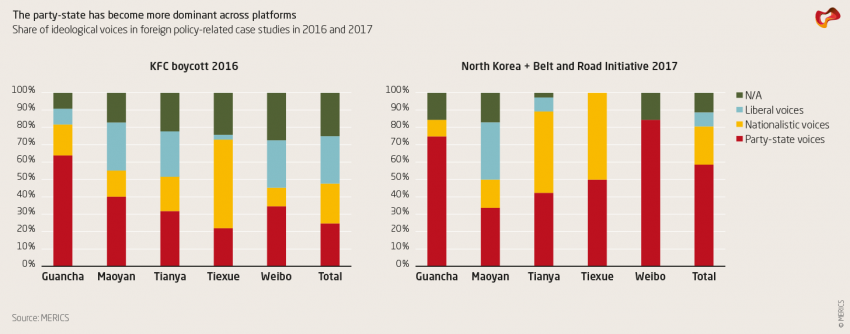

- While official party-state narratives seem to dominate the debate, the picture is more mixed across different social media platforms. On the nationalistic platform Guanchazhe (观察者) and the popular Weibo (微博), close to 80 percent of the posts represent the party-state position. Interestingly, not only on the more liberal forums like Maoyankanren (猫眼看人) or Tianya (天涯), but also on the nationalistic forum Tiexue (铁血), the share of party-state ideology (re-posts by private accounts excluded) does not exceed 30 percent.

- The party-state media narrative of a “China approach” (中国方案), which is portrayed as superior to inefficient and weak “Western” concepts, has penetrated debates on BRI and North Korea in social media.

- Divergent opinions on BRI and North Korea, however, continue to be visible. Participants mostly debate the question of whether or not the CCP is acting in the nation’s best interest.

- In comparison to our study on online opinions from 2016, liberal voices have been further marginalized across all social media platforms. The most visible change has been on Weibo: The share of liberal voices decreased from around 30 percent in 2016 to zero in 2017.

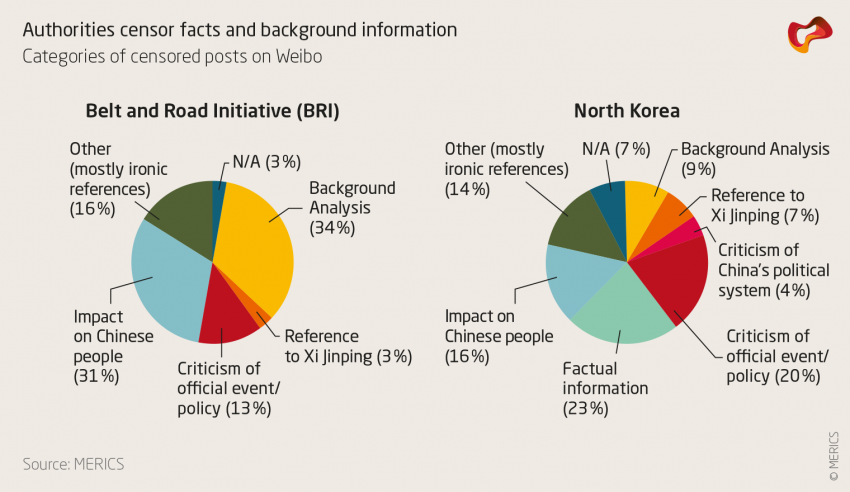

- Censorship mainly targets social media posts that contain information on potential risks to the Chinese public. Only a few topics seem to clearly cross red lines, namely any critical reference to Xi Jinping or to the Chinese political system or to the impact on Chinese people’s lives.

- Our findings indicate that the Chinese government allows a certain spectrum of dissenting opinions online. This suggests that the CCP feels confident enough to allow criticism in online debates in order to monitor and manipulate opinions online.

1. Introduction: assessing the state of online plurality in Xi Jinping’s “new era”

In August 2018, at the annual Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work, Xi Jinping declared that the CCP needs to ensure that “the party’s innovative theories fly into the homes of ordinary people.”2 Compared to the administration under Hu Jintao und Wen Jiabao, the CCP under Xi has shown a much greater concern with ensuring that everyone from high-ranking cadres to ordinary citizens fully support the CCP’s ideology.

In 2016, in order to understand whether and to what extent this is reflected in the actual spectrum of opinions, MERICS conducted a study of competing ideas and ideologies in China. The authors found a surprising plurality of opinions in Chinese online debates.3 This finding stands in stark contrast with the ambitions of the CCP to create a national ideology to unify China’s population and to legitimize its continued rule.

Since the publication of the study in early 2017, the CCP has tightened its grip on power even further, with Xi Jinping famously declaring at the 19th Party Congress that “the party rules over everything.”4 At the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March 2018, the party made it clear that it demands absolute loyalty towards the party and Xi.

Just like the 19th Party Congress in the fall of 2017, the NPC was first and foremost a show of party and government standing united behind the General Secretary. The Congress removed the presidential term limits and enshrined Xi Jinping’s contributions to party ideology in the Party Constitution and the Chinese Constitution under the long and unwieldy label of “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era.”

Even though Xi’s diminished presence in party-state media starting in July 2018 prompted brief speculation that his position inside the CCP may have weakened, other signs point towards reinforced attempts to present Xi as a leader of “historical importance.” Just in time for the 40th anniversary of the Reform and Opening Period, the Shekou Museum of Reform and Opening in Shenzhen replaced a relief depicting Deng Xiaoping on his famous 1992 Southern Tour with a quote by Xi Jinping.5

Regardless of Xi’s precise status inside the top leadership, the party’s demands for loyalty from all Chinese citizens continue. Arguing that strong party leadership is a pre-requisite for China to succeed, the CCP has begun strengthening its control over all areas of life.

A thorough restructuring of the State Council unveiled at the NPC has boosted the party’s control over areas previously managed by the state. The CCP has also reinforced its efforts to combat cynicism towards official ideology within the party and key groups within the population.

It is reasonable to assume that the claim to control everything has had consequences for what can and cannot be said online.

Legislative changes certainly suggest tighter control. Earlier cyberspace legislation primarily focused on the enforcement of real-name registration and banning “illegal content.”6 In 2017, the Chinese government started to reach into more channels of communication, closing in on more hidden spaces for pluralistic exchange of information and opinion.7 Targeting public discussion forums, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) issued stipulations in August and September requiring forum operators to establish mechanisms linking accounts to proper identification as well as a system to review all posts before publication. Also, chat group providers as well as administrators of private groups will be held liable for the content of discussions and required to store user data for six months and to apply a credit scoring system.8

Our goal for this publication was to understand what is left of pluralistic debates on Chinese social media in the “new era.” We analyzed two recent debates on issues of key importance to the Xi administration’s effort to establish China as a responsible, influential global power. The first debate revolved around an international crisis triggered by a series of North Korean missile tests in the summer of 2017. The second reacted to the first international summit of the “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)” hosted by China in Beijing in May 2017. We started by identifying the party-state line on those two topics by crawling articles from party-state media during the same time frame. We then used the official positions as a benchmark to identify the degree of divergence in online debates.9

We analyzed the data with regard to three questions:

- Overall, how much plurality still exists (compared to our previous study)?

- How much are official ideology and CCP talking points represented on the platforms that we crawled for the two debates in question?

- What are “red lines” for expressing and publishing diverging opinions?

2. Telling the CCP’s story well: the “China approach” as a framework for a better international order

The CCP wants to promote the “China approach” (中国方案), a term now used to set China’s “unique” political system and its party-state capitalism apart from alternatives in liberal democracies.

The CCP and party-state media frequently argue in favor of promoting the China solution as a model for other countries. The advocacy for stronger international involvement is couched in terms that are reminiscent of the party’s revolutionary past, stressing China’s international role and its obligation to “contribute to the progress of mankind.”10 This explicitly includes its political system and various other concepts, such as the “community of a shared future for mankind.”

In order to understand to what extent official ideology permeates social media, we have searched the two debates for references to the “China approach,” “Xi Jinping Thought,” as well as official CCP concepts and talking points related to the (supposed) superiority of a Chinese rather than a “Western” model. We wanted to know both what kinds of official talking points are commonly repeated on social media, and how much space they take up in the debate.

In our two case studies on North Korea and the BRI, official ideology has strongly penetrated social media. What is more, when comparing party-state media and social media narratives, a strong alignment in overall perspectives can be found.

In both debates, official positions posted by official accounts or reposted by private users (referred to as “Party Warriors”), dominated the online conversation (58 percent for North Korea and 60 percent for BRI). By contrast, in a similar foreign policy-related case study from 2016 (calls to boycott KFC in response to a UN court’s ruling against Chinese claims in the South China Sea11) only 20 percent of the posts represented the CCP’s “voice.”

One major theme in the debates on North Korea and the BRI can be found both within party-state media and on social media platforms: Although China has not caused the current crisis and dysfunctionality of the international system, it acts as a responsible player and provides alternative – and often better – solutions to the ones offered by Western countries.

On the BRI, social media posts take up terms and arguments from party-state media, but often go beyond the official framing of BRI as an open invitation and a “win-win concept” in which the CCP has no special stake. Social media authors comment on BRI as the most powerful tool with which China will be able to “overthrow Western powerful nation’s worldview” (“一带一路”经验正在颠覆西方大国观).

“What will the future look like in a world that is afflicted with so many ills? In this critical historical moment, a ’China prescription’ (中国药方, a ’China approach’ (中国方案) or a ’China model’ (中国模式), give the world hope. What is the BRI? It can be summarized in one sentence – it is an upgraded version of the WTO. It is a fundamental overthrow, not a correction of the old system of global order.”

User Lao Mei 00007 (老梅00007), Tianyaluntan, May 16, 2017

As the United States is described as “retreating from global leadership,” authors on social media platforms deem European countries as passive followers who are unable to shape their own paths.

“Why does Europe situate itself within the US American trade system? Why can’t they start their own network? The financial crisis in 2008 started in the United States, why did Europe lose more than America? As early as 2000, Europe could have had the capability to start a project like the BRI. I wonder how Europe feels about this?”

User Jixing Yihao (吉星一号), Tianyaluntan, May 17, 2017

On North Korea, both party-state media articles and social media posts state that the United States and North Korea are equally responsible for the escalation of events over the summer of 2017. Interestingly, some party-state media stress that China is not responsible – hinting at some existing critique concerning Beijing’s North Korea policy among Chinese scholars, which is also voiced within social media posts (see Chapter 3.2).

“China is affected the most by the current security situation on the peninsula. It is obvious that China makes a huge effort to solve the problem on the North Korean peninsula. The United States should understand that China is not causing the problem and also doesn’t hold a magic stick in its hand to solve it. The key to solving the issue is with the United States and North Korea.” (Xinhua Commentary, July 31, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/asia/2017-07/31/c_1121410324.htm)

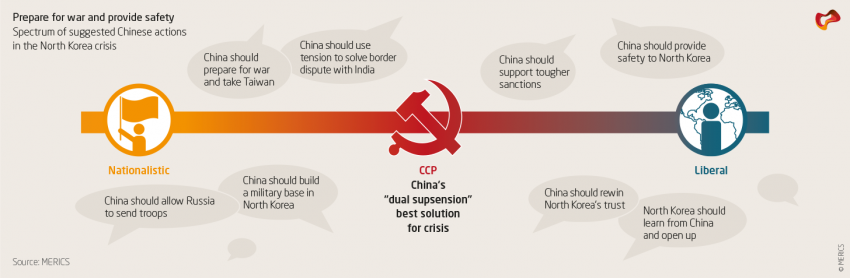

Still, both party-state media and social media promote the “dual suspension” (双停; North Korea stops launching and testing rockets/nuclear capacities while the United States stops military drills in the region) proposed by the Chinese administration as the best solution to ease tensions:

“(…)The best solution is still what China has advocated: to de-nuclearize the Korean peninsula and to set up a ‘dual track’ peace mechanism: Within a so called ‘double suspension’ framework, North Korea temporarily stops its nuclear activities while the United States and South Korea stop their joint military drills. On this foundation, the six-party talks should be reopened.”

User Qi yige meiren yong de mingzi (起一个没人用的名), Tianyaluntan, August 8, 2017

3. Plurality of opinion has decreased but not disappeared

While official party-state narratives seem to dominate the debate, the picture is more mixed when we compare forums. On Guanchazhe 观察者 and Weibo, close to 80 percent of the posts represent the party-state position. Interestingly, not only on the more liberal forums like Maoyankanren 猫眼看人 or Tianya 天涯, but also on the nationalistic forum Tiexue 铁血, the share of party-state ideology (re-posts by private accounts excluded) does not exceed 30 percent. Overall, however, taking all the social media platforms together, liberal voices have been further marginalized in comparison with our case study from 2016.

3.1 BRI: Social media debates focus on benefits for China

Party-state media posts emphasize that although BRI is initiated by China, it belongs to the whole world and everybody is invited to participate. Social media posts place a much stronger focus on national interest, highlighting BRI’s benefits for the People’s Republic.

“[Concerning the BRI forum in May in Beijing], one doesn’t have to take a long historical view. But it is the first time in 100 years that the Chinese people have really risen (中国人第一次要真正地站起来了).”

User Wangyuan (汪元), Maoyankanren, May 19, 2017

“Countries that don’t accept China’s Belt and Road will suffer heavily! (…) To cling (to the leg) of the United States or to lean on a stronger protector, China, this is the question Singapore needs to think about.”

User Shi wumao a (是五毛啊), Tiexueluntan, June 15, 2017

Some users who subscribe neither to official rhetoric nor to populist nationalist sentiments came up with more sober, pragmatic assessments of the strategic motives underlying the BRI, arguing that the initiative mainly served China’s national interests:

“The real strategic goal of BRI is – in the short run – to tackle serious domestic overproduction and existing overcapacity, and, in the long run, (…) to shorten the process of the internationalization of the RMB (…) and letting countries in [China’s] circle of friends jointly deal with the inflation that results from overissuing [China’s] currency. (…).”

User Bulao de A Gan (不老的阿甘), Maoyankanren, May 23, 2017

In conclusion, published and visible opinions on BRI diverting from the party-state ideology stretch towards both ends of the ideological spectrum. Liberal critics use economic arguments to support their viewpoint that the BRI is harming China’s national interests, while nationalists appeal to sentiment and history.

3.2 North Korea: party-state media praise Chinese leadership, social media users express doubts

Party-state media articles portray China’s “double suspension” solution as the best step forward to de-escalate the tensions between North Korea and the United States. Moreover, Beijing’s official position contains a strong emphasis on negotiation and diplomacy. The UN sanctions, which China has to a large extent supported, are framed as a means towards the goal of bringing North Korea (and the United States) back to the negotiating table.13

The spectrum of divergence from this official position within the analyzed social media platforms is remarkable. Challenges to the official line of argument, although far from being a large part of the posts, are raised from both the liberal as well as nationalistic end of the ideological spectrum.

Posts on the liberal end of the spectrum appeal to a self-assessment of the Chinese government:

“The United States is mainly to blame for the deterioration of the North Korean issue, but China cannot be a bystander, is has been drawn deeply into the conflict. (…) We need to ask, why did North Korea decide to develop nuclear weapons and doesn’t want to stop, claiming to feel threatened by the South Korean and US army? Why wasn’t China able to communicate with North Korea on providing a security promise and a nuclear shield?”

User Hongguan tianxia 6985 (鴻觀天下6985), Tianyaluntan, September 7, 2017

On the other end of the spectrum, some users even go as far as to suggest that a war in the Korean peninsula could present an opportunity for China to attack Taiwan:

“So, this [the tension on the Korean peninsula] is adding to risk of conflict in Northeast Asia. China should really prepare for military conflict, and solve the Korean peninsula conflict and also the Taiwan problem. This means, if Northeast Asia is at the brink of a war, China should support North Korea in a ‘proxy war,’ and we should consider to take Taiwan without much fuss, to realize the unification of the motherland.”

User Tianjian 62 (田间62), Tiexueluntan, July 30, 2017

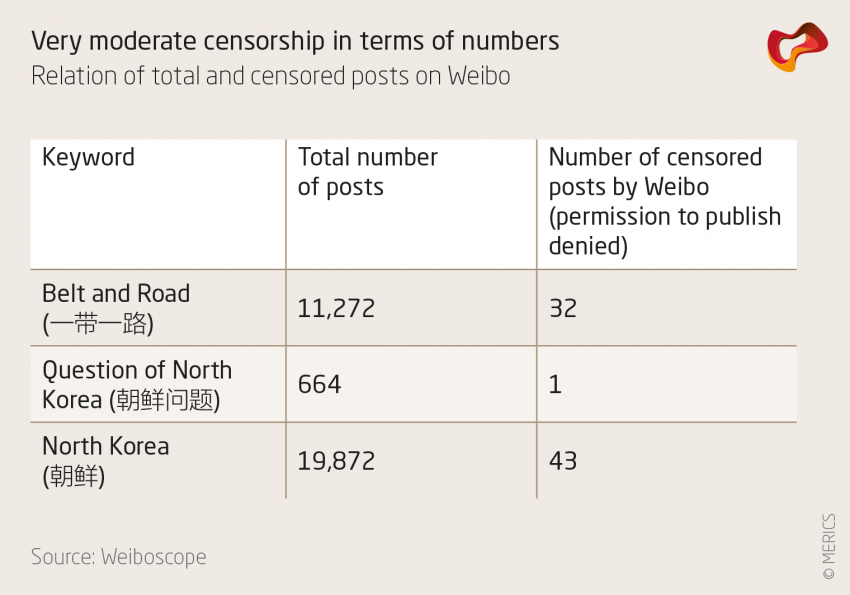

So far, we have only discussed uncensored opinions. To better understand whether online speech crosses a government red line, we have to take a closer look at the censored posts.

4. Censorship: Chinese authorities fear facts in online discussions

Judging from leaked censorship instructions that were published by the US-based independent media platform China Digital Times, reporting and discussions on North Korea were at least of some concern to the authorities. Within the time frame of our analysis, China Digital Times made public one such instruction on North Korea, related to the news of a hydrogen bomb test ordered by North Korean leader Kim Jongun. It called for the closure of the news comment function and for website editors not to “hype” it – meaning not to place this news among the top news.14 No similar instructions were leaked about the BRI (though they may have still been issued).

Due to the monitoring effort of Weiboscope, a Hong Kong-based social media data collection and visualization project initiated by Dr. King-wa Fu is Associate Professor at the Journalism and Media Studies Centre (JMSC), The University of Hong Kong, we were able to obtain and analyze a set of corresponding censored posts both on North Korea and BRI on Weibo.15

Three findings stand out:

Firstly, contributions containing (background) information are more likely to get censored than posts with nationalistic or any emotional content like slander or expressions of rage. In the case of the North Korea, the sole mentioning of anearthquake on Pyongyang’s soil [later confirmed to result from a nuclear missile rest] was censored, according to the censorship instructions obtained by China Digital Times. In the case of BRI, concerns that this project may stoke fears of hegemonic intent among China’s neighbors top the list of censored posts.

Secondly, only a few topics seem to clearly cross red lines, namely any critical reference to Xi Jinping or to the Chinese political system or to the impact on Chinese people’s lives. The latter aspect also covers a large part of the overall censored posts on both North Korea and BRI. In one BRI-related discussion, a seemingly common request about temporary traffic restrictions was censored:

“I am kindly asking people who are currently on the road to share how to get to from the Bejjing World Trade Center to Anzhen Bridge during the ‘Belt and Road summit’? I am asking about roads which the people can travel on?”

User Zhao Dabao (赵大宝), Weibo, May 15, 2017

One explanation could be that authorities sense a potential for offline protests at specifically named locations, as mentioned by other researchers on censorship in China. Adding to this observation is the fact that posts discussing real and potential dangers of the missile tests in North Korea are clear targets for censorship: the CCP seems to fear that eminent, collectively felt danger could mobilize people against the government. In the following example, the author blames the central government for failing to inform the population about potential health risk resulting from a North Korean nuclear test.

“The nuclear testing ground of North Korea is only some 400 miles away from Japan, and only 80 miles from the Chinese border, and only some 360 miles from Changchun and 450 miles from Harbin. Now, radioactively contaminated material has been discovered in South Korea, how about China? The Chinese environmental authorities haven’t issued any single statement on this, heaven only knows how things are. I would ask the Chinese authorities to clarify this. If we have an issue of pollution, people should move to Yunnan or Hainan...”

User Feiben de xiaolang (飞奔的笑狼), Weibo, September 15, 2017

Thirdly, many gray areas remain, since censorship is not consistent. While sometimes the very same critique on China’s North Korean policy can be found also among the Top 20 non-censored posts. Only nuances are considered too sensitive, e.g. arguments and/or evidence for strong undercover support for North Korea by Beijing and a critique that China’s fundamental assumptions about regime stability of North Korea being the top priority:

“Once the leader of this regime is replaced, North Korea will become a democracy (…) Today’s core interest of a state can then become tomorrow’s liabilities or even damage.”

User Xiangjunliao Zhenghua (湘军廖正华), Weibo, September 9, 2017

Concerning BRI, analysis of China’s underlying domestic economic problems as the main driver of the project can be found both among non-censored as well as censored posts. What the censored posts seem to have in common is that they mention specific phenomena like a real estate bubble, a distorted stock market and exported inflation.

Overall, judging from the content analysis, China’s censors target discussions that cast doubt on the party-state’s role as the only legitimate source of information and as the only authority capable of providing for the safety of the Chinese people.

5. Conclusion: opinion plurality – within limits

The ability of the party-state to dominate and “guide” public opinion on social media platforms has increased in comparison to our last study. Official narratives effectively penetrate social media, not only through posts authored by party-state actors, but also through an increased amount of reposted party-state media articles by seemingly private users.

Whereas private social media users often support official narratives, their opinions differ from party-state media in two ways: First, many display strong nationalistic sentiments or a feeling of superiority over other countries. Second, a minority of users (still) feels comfortable to criticize the government for either being too hesitant and weak (in the case of North Korea) or being too hegemonic, rude and unprepared (in the case of BRI). Still, quite a number of commentators on both the BRI and North Korea argue for the protection of China’s national interests.

Given the stricter control of social media, the degree of pluralism in these debates is remarkable. In the visible public sphere, the Chinese government still gets pressure from both ends of the spectrum: from the hot-blooded nationalists and from globally orientated, liberal voices.

One could argue that despite their sophisticated censorship system, the Chinese government will never be able to fully control the public online sphere – only if they decided to shut down all forums and/or heavily punish many authors.

However, for the following reasons, we find it more likely that the Chinese government pragmatically choses to ignore a certain spectrum of dissenting opinions.

First, as our analysis has shown, the party-state ideology, with the help of internal censors, algorithms and manipulated statistics, can control large parts of the discourse. Chinese authorities have managed to root out what they have perceived as threats from online public sphere endangering their own legitimacy and survival. They closed down pluralistic, highly professional online platforms like Gongshiwang (共识网) which could potentially align people from different backgrounds and interests, and they undermined efforts to organize bottom-up online (and potentially offline) protest by heavily punishing key political opinion leaders on Weibo, pressuring (and likewise punishing) IT companies if they don’t comply with control and censorship mechanisms even for private chat channels.

Therefore, going after too many different opinions is not necessary and might even prove counterproductive. Deleting every slightly dissenting post might mean larger numbers of angry, cynical social media users who would feel personally affected by the CCP’s censorship policies.

Second, by allowing a certain spectrum of debate, the Chinese government has the ability to monitor and test popular sentiment – always ready to censor if authorities feel debates are becoming too threatening.17 As earlier studies on censorship strategies have described, the CCP balances the so-called ”responsiveness benefit” (knowledge about popular sentiment in order to calibrate communication/propaganda on sensitive topics or crises) with potential image harm and risks for collective action deriving from non-censored opinions and debates.18

As our research has shown, in the case of North Korea there is evidence that the CCP chose to allow more space for critical debates to provide an outlet for frustration with the Kim regime, which had even built up within its own ranks.19

Third, as studies on media discourse in the context of central-local relations have shown, central government institutions can use publicly voiced critique to pressure other institutions or individual actors in the name of “the people,” diverting attention away from their weaknesses and/or boosting their own legitimacy.20

Looking at the results of our case studies, one might even ask to what extent the dissenting voices might have been planted or actively supported by parts of the political elites. For example, actors within the Chinese military might want to create popular support for a much tougher foreign policy vis-à-vis North Korea and/or the United States, potentially even pressuring the central government into military action. Or, taking the BRI case study, critical economists or private companies not profiting from this initiative might want to see a public discussion on wrong assumptions or underestimated risks.

One thing is certain: Despite the CCP’s efforts to establish ideological conformity, there is still a critical number of citizens who are not (yet) convinced or scared enough to offer alternative perspectives and moderately dissenting opinions.

- Endnotes

-

1 | The authors thank Bertram Lang, Yishu Mao and Felix Turbanisch who all contributed significant research and feedback to this study.

2 | 习近平出席全国宣传思想工作会议并发表重要讲话, August 22, 2018, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-08/22/content_5315723.htm, last accessed August 29, 2018.

3 | Shi-Kupfer, Kristin et al. (2017): Ideas and ideologies competing for China’s political future. MERICS Paper on China No. 5, October 2017, https://www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2018-01/171004_MPOC_05_Ideologies_0.pdf, last accessed September 30., 2018.

4 | http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/19cpcnc/2017-10/27/c_1121867529.htm

5 | Remaking History as Reform Anniversary Approaches. August 24, 2018, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2018/08/remaking-history-as-reform-anniversary-approaches/, last accessed August 28, 2018.

6 | Vanderklippe, Nathan (2018). Unpublished Chinese censorship document reveals sweeping effort to eradicate online political content. June 3. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-unpublished-chinese-censorship-document-reveals-sweeping-effort-to/, last accessed September 30, 2018.

7 | China tightens control of chat groups ahead of party congress. September 7, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-internet/china-tightens-control-of-chat-groupsahead-of-party-congress-idUSKCN1BI1PC, last accessed August 28, 2018.

8 | Sonnad, Nikhil (2017). In China you now have to provide your real identity if you want to comment online. August 27 https://qz.com/1063073/in-china-you-now-have-to-provideyour-real-identity-if-you-want-to-comment-online, last accessed September 30, 2018. In addition, draft regulations issued by the Ministry of Public Security in April 2018 include provisions about punishing internet service providers for not demanding real names of registered users.“ (http://www.mps.gov.cn/n2254536/n4904355/c6090144/content.html).

9 | According to pre-tested keywords and time frame (BRI: 一带一路, time period: May 14-August 14; North Korea: 朝鲜问题), time period July 4-October 4) data was crawled from five social media platforms (天涯论坛Tianyaluntan, 猫眼看人Maoyankanren, 观察者Guanchazhe, 铁血论坛Tiexueluntan and 微博Weibo, all of them appealing to different user groups) as well as as online website of party-state media (人民日报,光明日报,解放日报, 新华社,环球时报 and all 央视-related websites). All posts were then ranked according to their weighted reach (combining the number clicks, replies and forwards (the last two only for social media). Next, the Top20 post were coded according to sentiment (positive/neutral/negative) on “the West”, “multilateral perspective”, “national perspective”, “people perspective” and “party-state line”. Also, the Top20 posts of the social media articles have been attributed to the defined ideological clusters from our previous publication in 2016.

10 | As referenced, for example, in Xi’s Work Report to the 19th Party Congress. See http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping‘s_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf, last accessed August 29, 2018.

11 | Almond, Roncevert Ganan (2016). Interview: The South China Sea Ruling. The Diplomat, July 16, https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/interview-the-south-china-sea-ruling, last accessed on: September 30, 2018.

12 | For the sake of a clear-cut argument and better understanding, after the coding based on the ideological clusters defined in Shi-Kupfer et al 2017, individual clusters were combined into “party-state voices” (party-state ideology and Party Warriors), “liberal voices” (containing Humanists, US Lovers, Democratizers, and Equality Advocates) and “nationalistic voices” (including China Advocates, Flag Wavers, Mao Lovers, Industrialists and Traditionalists).

13 | Page, Jeremy et al (2018). China, Finally, Clamps Down on North Korea Trade – And the Impact Is Stinging. March 2. https://www.wsj.com/articles/north-korea-finally-feels-the-sting-of-international-sanctions-1519923280, last accessed September 30, 2018; Page, Jeremy (2018). China Widens Ban on Exports of Items Potentially Used in Weapons to North Korea. April 8. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-widens-ban-on-exports-of-items-potentially-used-inweapons-to-north-korea-1523238278?mod=mktw. last accessed September 30, 2018.

14 | Minitrue: No Hyping North Korea Nuclear Test, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2017/09/minitrue-no-hyping-north-korea-nuclear-test/, last accessed September 30, 2018.

15 | We thank Fu King-wa (https://www.researchgate.net/project/Weiboscope-and-Wechatscope) who shared data from his research.

16 | See e.g. King, Gary et al (2013). How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression. American Political Science Review, 107, 2 (May), pp. 1–18, http://j.mp/2nxNUhk, last accessed September 30, 2018.

17 | See Han, Rongbin (2018). Contesting Cyberspace in China: Online Expression and Authoritarian Resilience. New York: Columbia University Press.

18 | Plantan, Elizabeth / Cairns, Christopher (2017). Why Autocrats Sometimes Relax Censorship: Signaling Government Responsiveness on Chinese Social Media. July 12, http://www.chrismcairns.com/uploads/3/0/2/2/30226899/why_autocrats_sometimes_relax_censorship.pdf, last accessed September 30, 2018.

19 | Boc, Anny (2017). China‘s North Korea Debate: Redrawing the Red Line., The Diplomat, November 22, https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/chinas-north-korea-debateredrawing-the-red-line/, last accessed September 30, 2018.

20 | See Chen, Dan (2017). Supervision by Public Opinion or by Government Officials? Media Criticism and Central-Local Government Relations in China. In: Modern China, Vol. 43, No. 6. pp. 620–64.