3. The party state’s emerging toolkit gets companies in line

You are reading chapter 3 of the report "The party knows best: Aligning economic actors with China's strategic goals". Click here to go back to the table of contents.

Key findings

-

Xi isn’t unwinding earlier reforms, but is giving the party-state a stronger role in shaping the ecosystem that economic actors must navigate.

-

Breaking from the old model where SOEs advance national goals while POEs drive growth, Xi seems ambivalent about ownership and instead has varied goals for firms based on their relevance to his strategic goals.

-

Beijing is using a toolkit of policies, regulations and informal instruments to reshape economic actors that do not align with strategic goals, or to direct support to firms that are on board. Ownership/governance, carrots, and sticks are the key tools.

-

The government understands that private firms often have the dynamism and creativity SOEs lack to innovate and commercialize emerging technologies - key ingredients for China’s new development agenda – but that they sometimes need steering to develop the ‘right’ technology.

On the surface, it might seem the market reform process is advancing, if not even accelerating. Xi Jinping rhetorically supports the “decisive role of the market” and he and his cadres often repeat the line that private firms provide “50 percent of tax revenue, 60 percent of GDP, 70 percent of innovation, and 80 percent of urban employment.”15 The share of private companies in key sectors and their presence in the top 100 companies has steadily increased.16

China’s financial markets have also become more sophisticated. Private companies are omnipresent and financial markets have adjusted to serve the needs of these innovation drivers. Over the past 15 years, stock exchanges like ChiNext (2009), STAR Market (2019) and the Beijing Stock Market (2021) were launched to provide funding for the country’s fast-growing companies that were not adequately served by the state-owned banking system. Venture capital also grew alongside new investment channels for foreigners, such as the stock connect mechanism, which allows participation in Chinese capital markets like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. 17

Today, such market reforms are not being rolled back but the function and scope of prices determining economic activities has become far more restrictive. Prices as a coordinating mechanism fluctuate within a lower and upper band in which the government is comfortable, similar to the managed exchange rate of the renminbi (RMB). Sudden and rapid changes increasingly trigger a policy response to “correct” the market. Faced with increasing capital outflow pressure from a depreciating exchange rate, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) introduced an opaque “counter cyclical factor” – an adjustment to daily yuan quotes by the central bank – to “help” guide the market.18 Another prominent example was the heavy-handed government intervention during the stock market crash in 2015 or interventions to manage commodity prices in 2021.19 With increasing levels of intervention, prices are losing their significance as a regulator in the economy. Increasingly, the CCP is the deciding factor determining levels of supply, production, and investment.

3.1 Xi isn’t unwinding earlier reforms, but is giving the CCP a stronger role

As private companies have gained a foothold in strategically relevant sectors, the CCP has had to develop a new disciplinary system and incentive structure to compel rent-seeking entrepreneurs to serve the party’s interests. This was done in part by regulatory intervention in previously largely unregulated sectors. To increase political and operational control over private companies, regulatory measures have been complemented by stronger party affiliation of the management and traditional economic guidance tools via the state-controlled financial system. As the structure of the economy has changed, the party-state has supplemented its toolkit, turning increasingly to the private sector to achieve ambitious national priorities.

As demonstrated with Alibaba, Beijing is using this growing set of policies, regulations, and informal instruments to reshape economic actors that do not align with strategic goals, or to direct support and guidance to firms that are generally on board. These new tools fall broadly into three categories: Ownership/governance, sticks, and carrots. These are discussed briefly here but are illustrated in detailed case studies at the end of this report.

Ownership/governance

- Direct ownership

- Mixed-ownership/reverse-mixed-ownership

- Golden shares

- Party roles in decision making

- Market access restrictions

- Vertically integrated value chains

- Facilitated investment/divestment

Ownership/governance tools give Beijing direct influence in the decision-making processes of economic actors. Some of this happens through traditional means like direct ownership of SOEs at the central or even local level of the government, or through market access restrictions that have historically forced foreign private companies into joint ventures (JVs) with (often state-owned) local partners, thus creating channels for the party-state to guide decisions.

Others are the result of more recent efforts like mixed ownership reform efforts that in many ways tied SOEs and private companies together, or the application of golden shares in certain companies to ensure the party-state has certain veto powers. Finally, the party-state has other unique means to intervene, such as through party roles of board members, the ability to facilitate investment or divestment (to offload toxic assets from firms like the troubled real estate behemoth Evergrande or to raise funds through rapid sales like tech giant Huawei did with its Honor smartphone brand), or the ability of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) to use its ownership of multiple SOEs in a given value chain to coordinate action.

Sticks

- Regulatory direction

- “Crackdowns” and “rectifications”

- IPO blocks

- Common Prosperity demands

- Assignment to “national teams”

Sticks in Beijing’s arsenal give it the means to drive unruly actors away from the things Beijing doesn’t include in its objectives. This can happen through traditional regulatory direction, both to drive legitimate compliance (like with the new cyber and data legal regime) or as means of political signaling through “crackdowns” and “rectification campaigns” (like choosing the internet platform sector for its first round of cyber and data rules enforcement to send a message to other industries). This can also include steps like scuttling planned IPOs at the political direction of Xi himself. Some sticks don’t look so offensive or damaging, but instead are means of atonement, like embracing Common Prosperity by putting billions into common prosperity funds or joining “national teams” to help close strategic technology gaps.

Carrots

- Direct subsidies/tax relief

- Policy banks

- Cheap loans

- Advantageous stock listings

- Implicit guarantees

- State guidance funds

- Little Giants status

- HNTE status

- Ensured customer base

- R&D support

- Protected home market

Carrots are a way for Beijing to direct support to economic actors already aligned with national goals to help facilitate their success. They include many traditional means of state aid like subsidies, tax relief, cheap loans from state-run commercial and policy banks, implicit guarantees for SOEs, and protection from foreign competition. However, new support mechanisms have emerged in recent years to help achieve strategic goals, especially those related to closing the tech gap: advantageous stock listings in tech- and SME-specific markets, state guidance funds, status as a Little Giant (small firms in important areas of development) or as a High and New Technology Enterprise, ensured customer bases through public procurement or support from SOE customers, and extensive support in R&D through China’s innovation chain strategy.

3.2 The growing cast of roles for POEs

Economic policies increasingly focus on private enterprises, particularly high-tech small and mid-size enterprises (SMEs), as key actors to solve core issues like technological bottlenecks and economic self-reliance (see Exhibit 7).

The tech sector has benefited from “walled gardens” protecting them against foreign competition. Now that they have blossomed into strategically relevant companies, the CCP is beginning to tighten its grip. Private firms’ increasing prominence in policies also entails greater party-state guidance to focus on core objectives (see Exhibit 8). Prominent cadres call on private enterprises to “continuously increase S&T innovation efforts […] and to strive to become the force to solve the bottleneck technology problem.”20 The government understands that private firms often have the dynamism and creativity that SOEs lack to innovate and commercialize emerging technologies, which are key ingredients for China’s new development agenda.

The greater guidance of private enterprises is accompanied by new carrots and sticks. If private companies follow party-state guidance, they stand to benefit from direct and indirect policy support and improved financing options. A top-level policy published in 2019 by the CCPCC and the State Council is directed at improving the business environment and financing options for private firms to harness their innovation for national goals.21 Furthermore, the party has greater expectations of the private sector to fulfill national priorities and “unswervingly listen to and follow the party at all times.”22

This does not mean that all companies are tightly controlled by the party-state – far from it. The bulk of private firms fall outside of the areas deemed strategically relevant by Beijing. Even in some important industries like the new energy vehicle (NEV) sector, which is critical for China’s green transition and is also an important growth sector where Chinese firms are on the cutting edge, the party-state has given considerable space to private actors.

It has adopted a surprisingly lax approach to directing NEV makers while also throwing mountains of state aid into the sector to drive up demand – effectively dedicating a large field where contenders could take root with ample fertilizer for all. Only after some NEV makers emerged as commercially viable did Beijing begin to tighten standards and cut off state-aid – eventually leading the weakest players to exit the field and leave the remaining space to China’s most promising NEV brands.

Since at least the 2013 Third Plenum, the leadership has been optimizing economic policies in order to establish a more efficient economic system (driven in part by market forces) that also responds to the guidance of the party. Xi recognizes the superiority of a competitive environment in allocating economic resources in terms of market efficiency for the purposes of growth and general development. However, in areas where investment would not be efficient from a market perspective, but where the leadership urgently needs China to be technologically competitive on a global scale, party-state intervention is essential. From the perspective of the CCP, this is not seen as a contradiction.

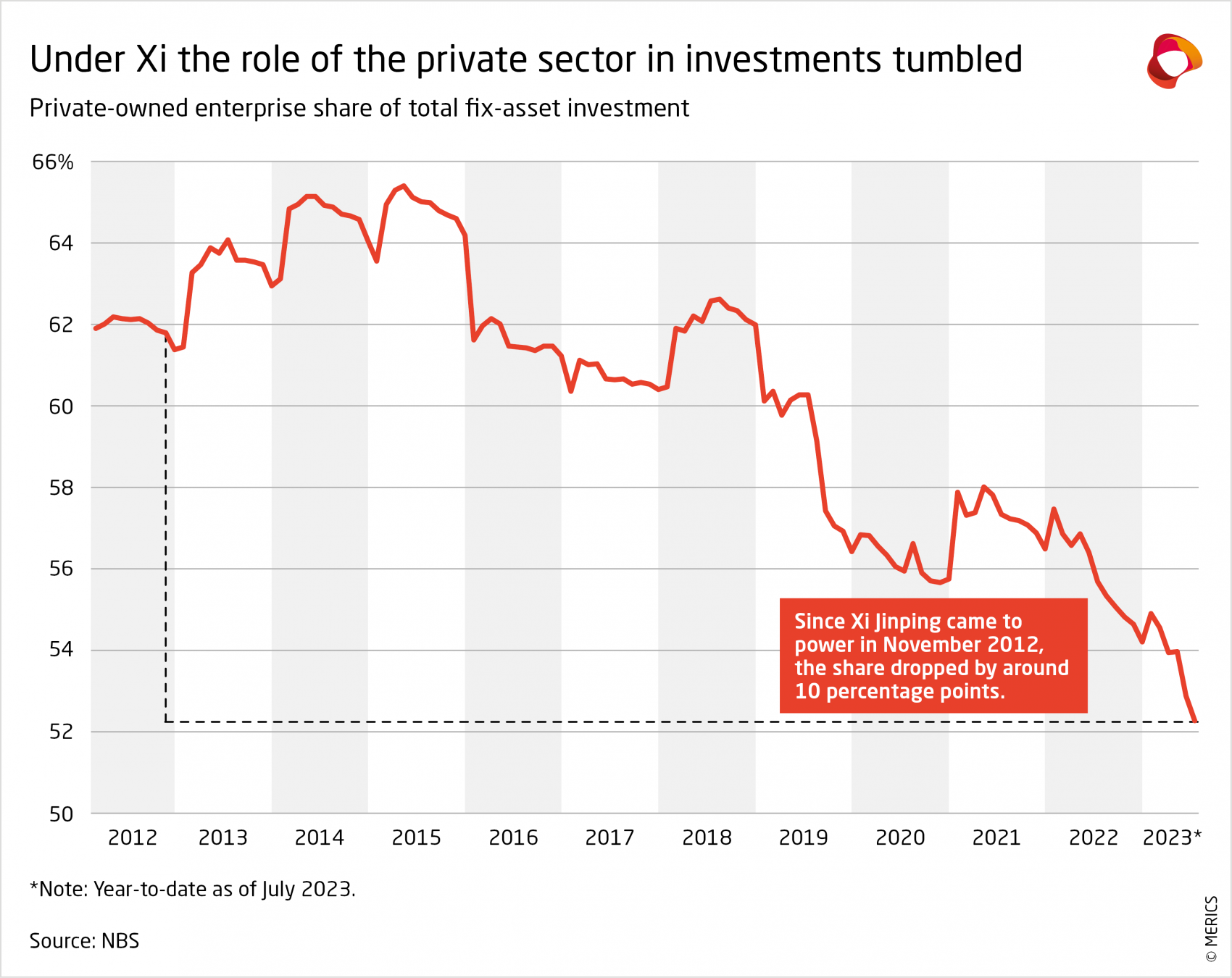

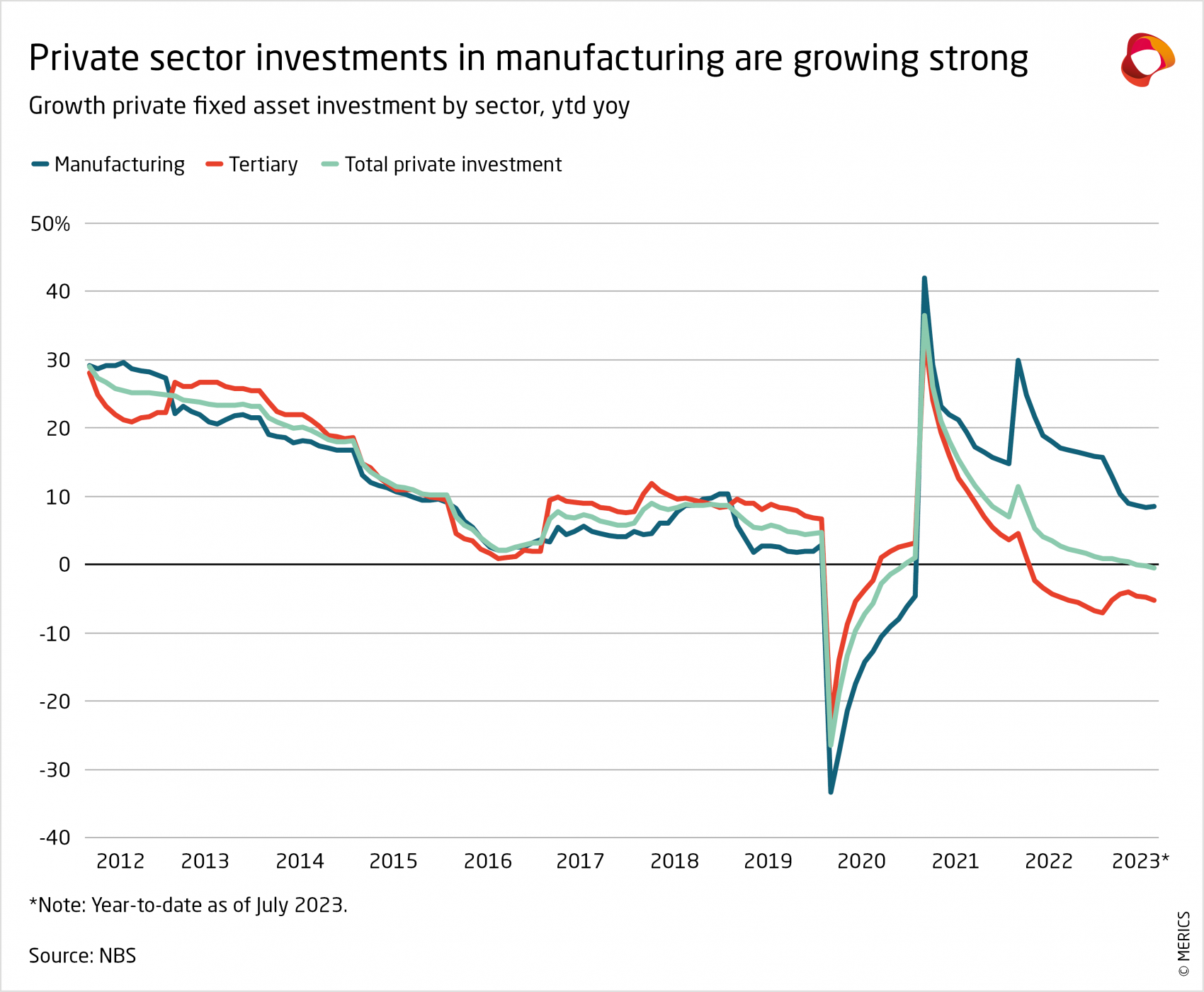

In Xi Jinping’s era the share of POE in China’s fixed asset investment has deteriorated by nearly 10 percentage points. Despite these notable shifts, China is not a command economy in which all companies follow the party overlord by investing in the “real economy.” The deterioration of POE investment is mainly due to a slowdown in services and real estate, while investment in manufacturing has been growing in the double digits.

But the private sector remains fairly reluctant to follow the CCP’s growing influence, requiring the CCP to develop new tools for control and guidance. Private companies continue to have similar opportunities as in far more capitalistic systems. But market mechanisms, including how private companies and financial markets operate, are increasingly guided, if not dominated, by the CCP. All in all, the CCP is trying to come up with a system of economic rules that forcefully merges party control with market mechanisms.