6. China contends for the central position in the global economy

You are reading chapter 6 of the report "The party knows best: Aligning economic actors with China's strategic goals". Click here to go back to the table of contents.

Key findings

- China is reinforcing and strengthening controls over international trade and finance, in- and outbound investment and the flow of data and people that make up “fortress” China.

- Xi sees that China must remain connected to the global economy to advance its development and expand its global power – but is wary of unfettered, Western-style globalization.

- It is not in China’s interest to completely disconnect with liberal market economies, as it still needs their markets for exports and capital and technology to overcome tech dependencies.

- Similarly, Beijing aims to build up ties with global south countries as raw material sources, growing export and investment markets, and destinations for China’s tech and capital.

- Key features of China’s global engagement: challenging the existing economic order, mitigating risks with liberal market economies and engaging with emerging and developing countries.

Throughout the reform process initiated under Deng Xiaoping, China’s foreign economic policies remained highly restrictive and controlled – most notably, its strict capital controls and restrictions on foreign investments. The general mantra of hedged integration with the global economy has not changed under Xi Jinping. But the parameters for China’s future opening are increasingly happening on its own terms. In the process, China is reinforcing and strengthening controls over international trade and finance, in- and outbound investment and the flow of data and people that make up “fortress” China. It is also a reminder that the relative trade openness that has been a key driver for China’s integration over the past decades is more the exception than the norm for China.

Global economic integration should now be on China’s terms to safeguard its national interests and long-term economic development. The objective is to create economic and technological dependencies by developing new markets, controlling value chains and securing access to key resources for China’s industry, energy, and food needs. Instead of pursuing Western-style globalization driven by capitalism, China is seeking its own path consistent with greater party control and guidance. A world in which companies act independently from national strategic goals in pursuit of profitability conflicts with Xi’s economic principles. National interest should take precedence over profit-driven motivations. Beijing recognizes the need for China to remain connected to the global economy to advance its development and expand global power – but is wary of unfettered, Western-style globalization.

However, China is not on a path towards isolation. It is not in China’s interest to completely disconnect with liberal market economies, as it still needs their markets for exports and needs its capital and technology to overcome existing tech dependencies. Providing economic incentives is also an effective tool to keep countries in line with China’s interests and positions. To facilitate this, China is highly active in deepening ties with the Global South as it seeks to develop new alternatives.

Three key features of China’s engagement with the world are: challenging the existing global economic order, mitigating risks with liberal market economies and engaging with emerging and developing countries.

- Challenging the global order: The leadership’s efforts to strengthen China’s position as a global economic power lacks neither vision nor ambition. China is doubling down in its effort to pull more and more countries and companies into its sphere of economic influence. The BRI has helped China expand its trade faster and served as a new source of external demand. Investment-driven engagement has focused on building hardware, complemented by agreements to provide the software to run it. US economic sanctions and concerns that American global hegemony is waning have provided China additional inroads and growing economic clout. In response to geopolitical shifts, China has accelerated its efforts by rolling out numerous new initiatives. In 2022, it launched the trinity of the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Instigative (GSI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). Older formats such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization formed in 2001 seem to have gained new momentum.

- Shifting the economic center of gravity: Ideally, China should provide an alternative if not replace the dominance of liberal market economies as a global provider of technology and capital. While expanding economic ties with liberal market economies was a catalyst for China’s development in the past, China is now seeking greater engagement with the Global South, promoting development in these new markets to cultivate new customers for its exports. It portrays itself as the champion of the Global South, which frustrated with the American-led world order that leverages the gravitational pull of its economy. In a shifting global context, China’s multifaceted set of policies are finding welcome takers around the world.

- Develop China’s own de-risking strategy: Just as voices in advanced economies say there is no second China as a market, the reality is that there is no second set of liberal market economies for China when it comes to technology, capital, and demand for Chinese exports. While it aims for autarky, China is not in a position to cut all foreign dependencies without massive implications for its own development. One way is by absorbing global value chains though greater localization of foreign companies. China has opened up many sectors to foreign investment to onshore key technology providers – ironically, opening up in such areas advances technological self-reliance by bringing foreign technology under Beijing’s jurisdiction.

Tracking integration: The shifting dynamics of China’s careful opening up

François Chimits

The globalization that has driven China’s engagement with the world is undergoing a structural break, with new risks and opportunities for China to shape its own position. To understand the direction China is taking in its relationship with the rest of the world, it is critical to examine its changing patterns of trade, investment, technology and finance. Two case studies at the end of this chapter cover how an emerging global tech leader in the EV space, BYD, as well as the old state-owned national shipping champion, COSCO, contribute to the strategic goals of Beijing at home, but especially overseas.

6.1 Trade: China wants to develop new export markets and increase dependencies on the Chinese market

Growing trade ties have long been the key driver for China’s global integration. China overtook the US as the biggest trade partner of 71 percent of the world in 2021.87 Gaining access to the large Chinese market is an irresistible lure to deepen ties with China, including through new bilateral or regional trade agreements. After years of booming trade with advanced economies, export volumes are nearing saturation, but with 40 percent of China’s exports going to the EU, US, and Japan in 2022, developing new export markets is still an uphill battle. Regional trade deals like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RECEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) are useful for Beijing to build regional supply chains and markets, especially in Southeast Asia where more geopolitically neutral countries in its immediate neighborhood are less likely to sign on to what China perceives as US containment efforts.

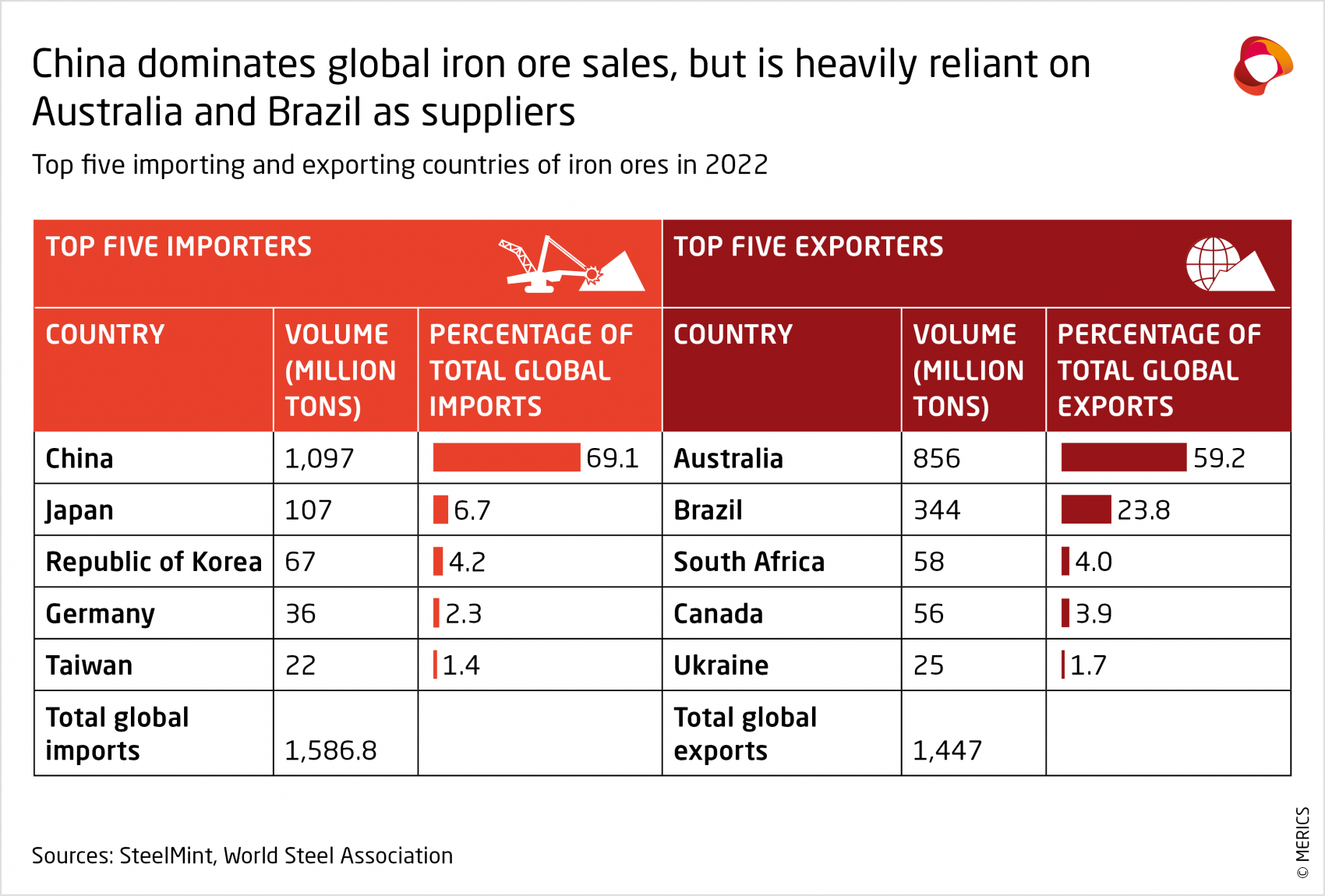

China is still heavily dependent on a few Western countries for high tech but also for key commodities (e.g., US for soy or Australian iron ore and coal). While self-sufficiency is a feasible solution for reducing tech dependencies, diversification efforts facilitated by the BRI are a key for commodities that China lacks (e.g, Brazil for soy and iron ore) – after all, no effort from Beijing will make iron ore spontaneously materialize within China’s borders (see Exhibit 17).

China is now focused on deepening ties with the Global South. China’s strategic engagement with emerging countries expanded its global economic footprint and helped to improve food security and access to raw materials including ones critical for the energy transition. Starting December 1, 2022, China reduced trade restrictions on nine African countries for over 8,000 items and the pursuit of trade deals in Latin America for market access and securing commodities.89

China has much to gain from providing better market access, especially for exports of commodities and lower value products, while competition in higher value goods with advanced economies will likely impact the trade structure. However, during a meeting of the Central Finance Committee (中央财经委员会) in May 2023, it was stressed that China should not give up on low end industry and instead transform it, as it provides an important foundation for manufacturing.90

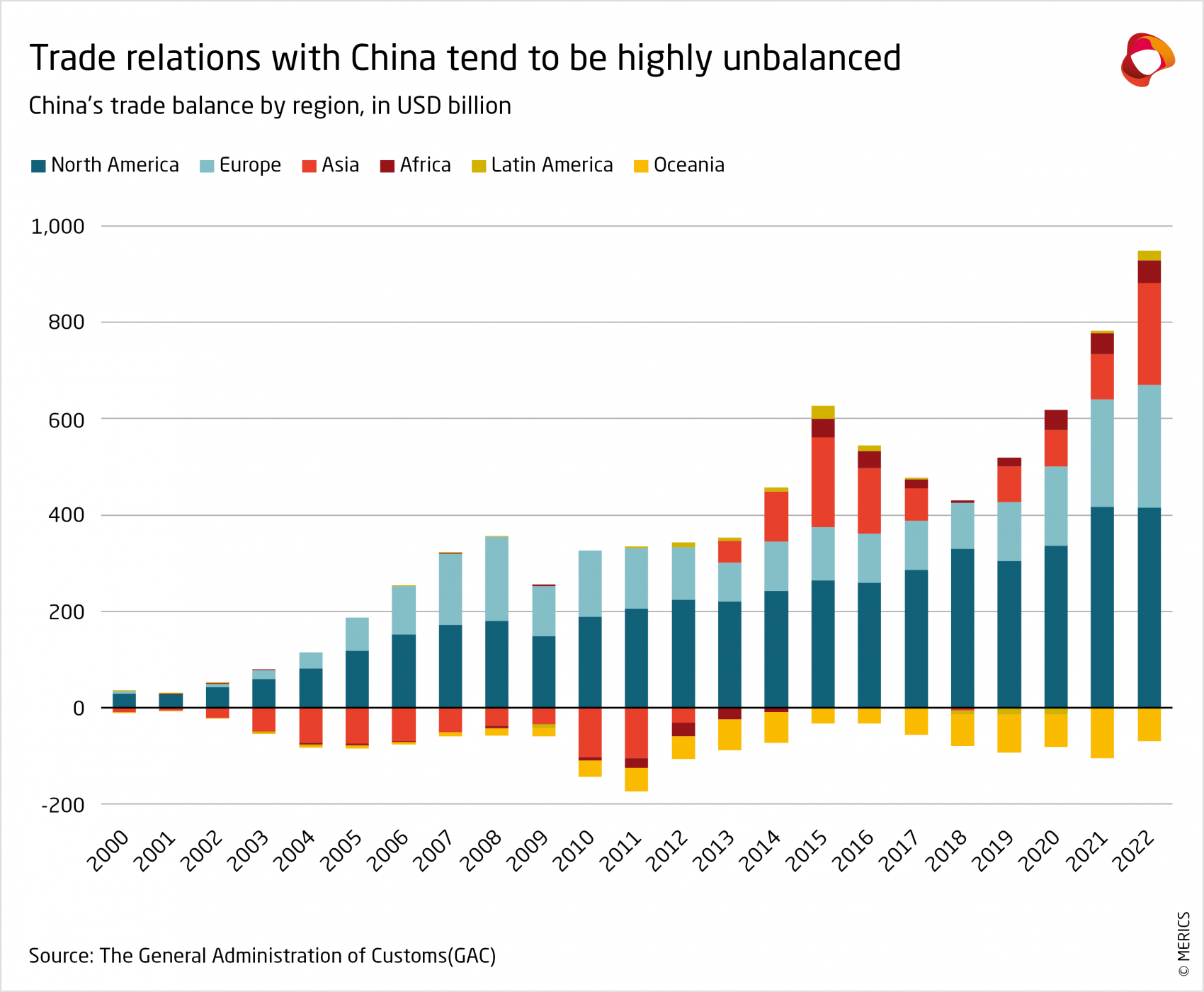

China’s trade structure will need to considerably change, becoming less export driven and relying on more diversified import structures beyond commodities and high tech. Growing trade is often accompanied with a growing trade deficit due to China’s dominance in manufacturing. China has a trade deficit with only around 20 countries – all commodity exporters with the exception of South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Switzerland. But the sheer size of the Chinese market remains the government’s biggest driver for deepening economic ties. For emerging economies, it provides a welcome alternative to Western markets, while for advanced economies deeper trade should act as a bridge over the growing political divide (see Exhibit 18).

6.2 Investment: China wants to become a key investor in emerging economies and attract high-tech investment

China has been a long-term recipient and beneficiary of foreign investment and continues to open access by trimming its negative list that restricts foreign investment in certain sectors and revising the catalogue for sectors that encourage foreign investment. Slower growth prospects, geopolitical risks and a more restrictive political environment has tarnished China’s appeal for many foreign companies. Coupled with a weaker global economic outlook, foreign direct investment (FDI) in china fell to a 25-year low in the first half of 2023.91 FDI now more than ever is focused on helping close technological gaps and improve supply chain resilience. This means companies in high-tech sectors can expect red carpet treatment to onshore high value-added production and R&D. The importance and concern of dwindling FDI has let the State Council released a new set of measure aimed at attracting high quality investment in August 2023.92

During the last decade, China has started to establish itself as a major investor overseas. Initially, Chinese investments were focused on developing countries. The BRI, launched in 2013, and the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2015 were prominent efforts in Xi’s ambition to strengthen China’s position in the world. China does provide an attractive alternative for many developing countries – and one that does not tie investments to issues of human rights or environmental protection. Central elements of the BRI and the AIIB have been their emphasis on financing and infrastructure projects to meet their transportation, communication and energy infrastructure demands in foreign countries. But there are also examples of dedicated development zones such as the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone in Cambodia.

Despite criticism of being a potential debt trap and pushback in some regions amid disappointment about delivering on pledged investments, the initiatives have yielded tangible results. China is seen as a partner for economic development for a wide range of projects from infrastructure to dealing with climate change.

In developed countries, Chinese companies have also started to gain traction as an investor. In 2016, Chinese firms invested a record EUR 47.5 billion in EU27 and the UK.93 However, investment has steadily slowed. In 2022, Chinese investment in Europe was only EUR 7.9 billion, down 83 percent from the 2016 peak. The decline is caused by tightening capital restrictions in China – to prevent investments in non-strategic areas such as football clubs or real estate – and political and regulatory pushback in the US and Europe that has made it more difficult for Chinese firms to conduct merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions, especially in critical infrastructure and technology assets. As in 2022 M&A fell to its lowest levels since 2011 (EUR 3.4 billion), record greenfield (EUR 4.5 billion) has become new bright spot of Chinese investments in Europe, albeit fragile for now because this has targeted only a few sectors, primarily EV batteries.

Despite China’s surging outbound investment in the last decade, investment relations between liberal market economies (liberal market economies) and China remain heavily uneven. While companies from those countries continue to invest heavily in China, the same is not true in the reverse. By 2021, European firms have invested an aggregated EUR 233.6 billion in China which is more than three times the amount that Chinese firms have invested in Europe (EUR 69.9 billion).94

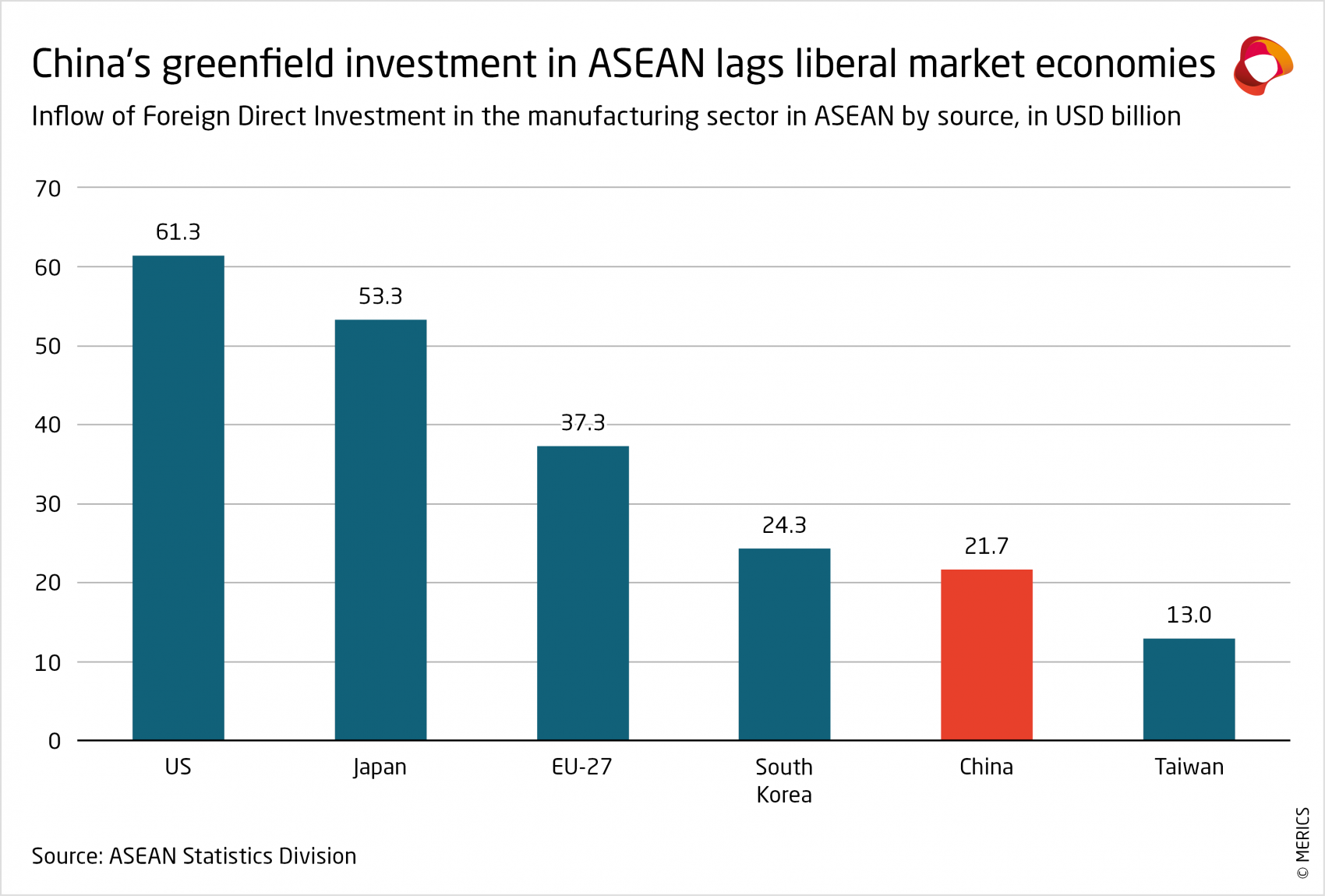

China’s role as a global investor is likely to increase but will be met with more competition as liberal market economies roll out new development projects in response to the BRI. The investment structure will need to shift more from infrastructure and M&A to greenfield investments, increasing the international exposure of Chinese companies. As of now China’s investment in manufacturing in ASEAN, for example, significantly lags those of the US, EU or Japan (see Exhibit 19).

6.3 Technology: China wants to expand its footprint to become a global provider

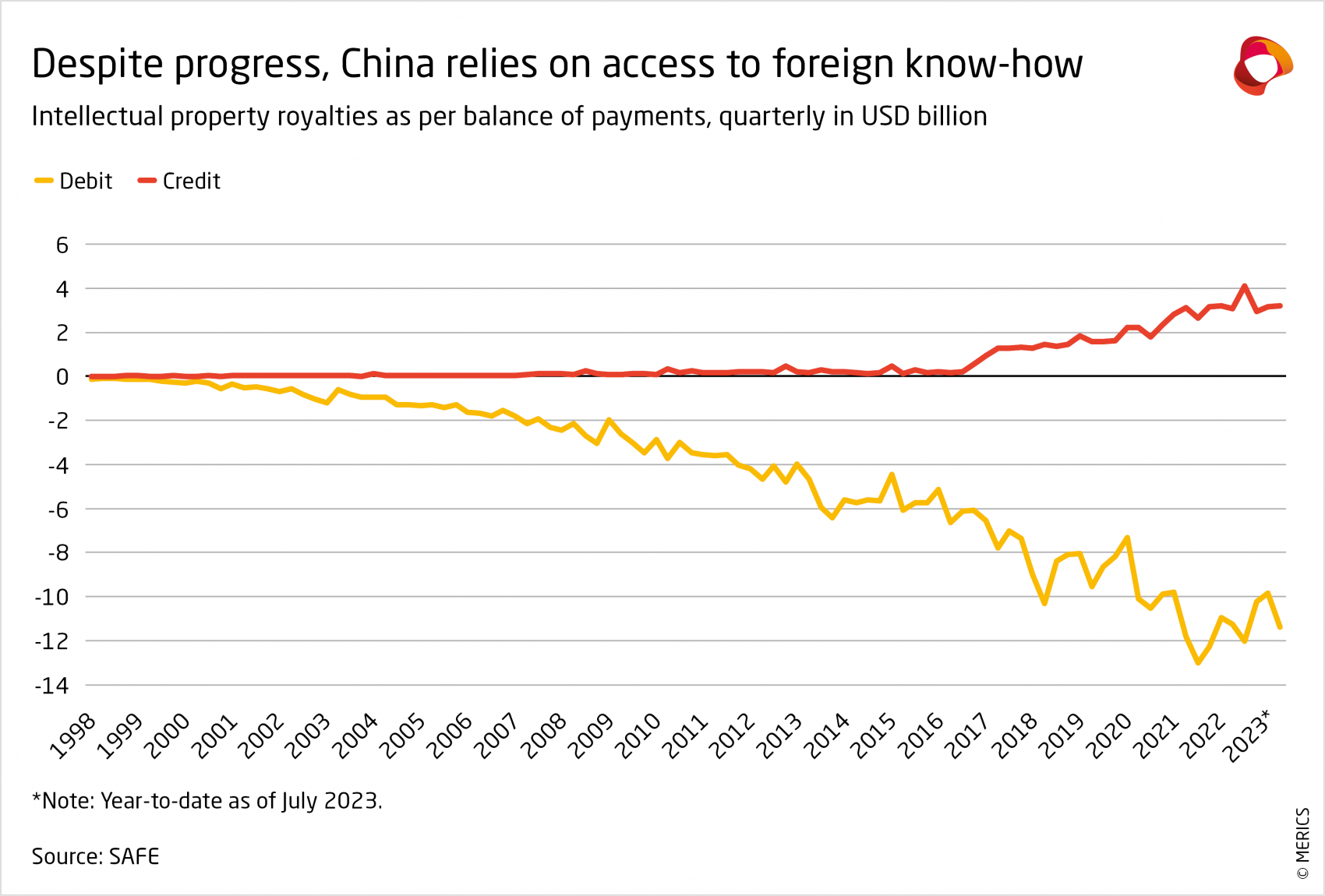

China can still tap into global knowhow via its overseas students or by acquiring crucial licenses. For example, the MCCI sub-index on intellectual property rights (IPR) imports reached 0.52 in 2020, indicating a high level of integration. Access to foreign IPR is essential for China to continue to expand its industrial capabilities. But China has already evolved into a viable provider for technology, issuing IPR of its own, with strong growth since 2017 (see Exhibit 20). Companies from Huawei to Xiaomi are household names in the area of consumer electronics. Chinese companies can provide a wide range of products from 5G networks to high-speed railway systems and energy solutions (including green tech).

Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December 2022 was a demonstration of China’s attractiveness as a development partner. The deal signed included commitments on developing hydrogen energy, data centers and EV factories in Saudi Arabia. Digital companies have expanded their footprint as technology providers from artificial intelligence, e-commerce and mobile payment applications to communication, smart cities and surveillance equipment. In November 2022 alone, China completed e-commerce agreements with Laos, Thailand, Singapore and Pakistan (see Exhibit 20).

China’s growing technological clout is a result of its improved innovation capacity. High-tech companies in liberal market economies now consider it essential to be part of the Chinese innovation ecosystem by expanding R&D capacity to safeguard their global competitiveness.95 It is an indispensable location for foreign companies, especially in dynamic sectors like digital applications, smart manufacturing and electric/autonomous vehicles. China will leverage its growth potential and improved position in the high-tech sector to make it an irresistible market for high-tech companies.

Maintaining access to technology remains vital for China’s future ability to innovate. China is successfully engaging abroad to help create demand for Chinese technology. While its engagement in emerging countries is more focused on government-to-government relations, China is increasingly building on ties to companies in liberal market economies. In an attempt to tie them into China’s innovation system, they hope to make international access to technology more resilient.

6.4 Finance: China wants to provide an alternative to the USD-dominated financial system

After years of promises and the opening of China’s financial markets in theory, real capital flows are now materializing. Strict capital controls remain in place, but China has expanded existing channels and introduced new ones to connect (e.g., Hong Kong Stock Connect or the Shanghai-London Stock Connect) its financial markets with the world.96 While in the past financial integration was mostly a one-way street with Chinese purchasing equities (including of Chinese companies listed abroad) and bonds (including US treasuries), the picture is now becoming more balanced. The sophistication and complexity of China’s financial system has greatly improved, creating an additional pull for foreign investors to participate. This includes issuing CNY-denominated bonds in China and expanding offshore financial markets.

Existing capital account restrictions and growing political risks are likely to keep liberal market economies’ investors underinvested in China relative to its share in the global economy. But gradual financial integration is likely to remain a key driver for China’s global economic ties as it provides alternatives for advanced and emerging economies alike.

China is also actively trying to break USD dominance in global trade settlement. New hope rests on the introduction of the e-CNY, the PBOC’s digital currency, as well as CHIPS, the alternative to the current global payment system SWIFT. For Russia, this has provided a helpful alternative, as the Chinese currency was used for 17.9 percent of settlements in 2021, up from 3.1 percent in 2014.97 In 2023, agreements with Saudi Arabia, Argentina, and Brazil aimed to increase use of the CNY for trade with China (e.g., via swap agreements between the central banks). The CNY’s internationalization will likely accelerate but with limitations, as this would require China to give up its strict capital account controls.

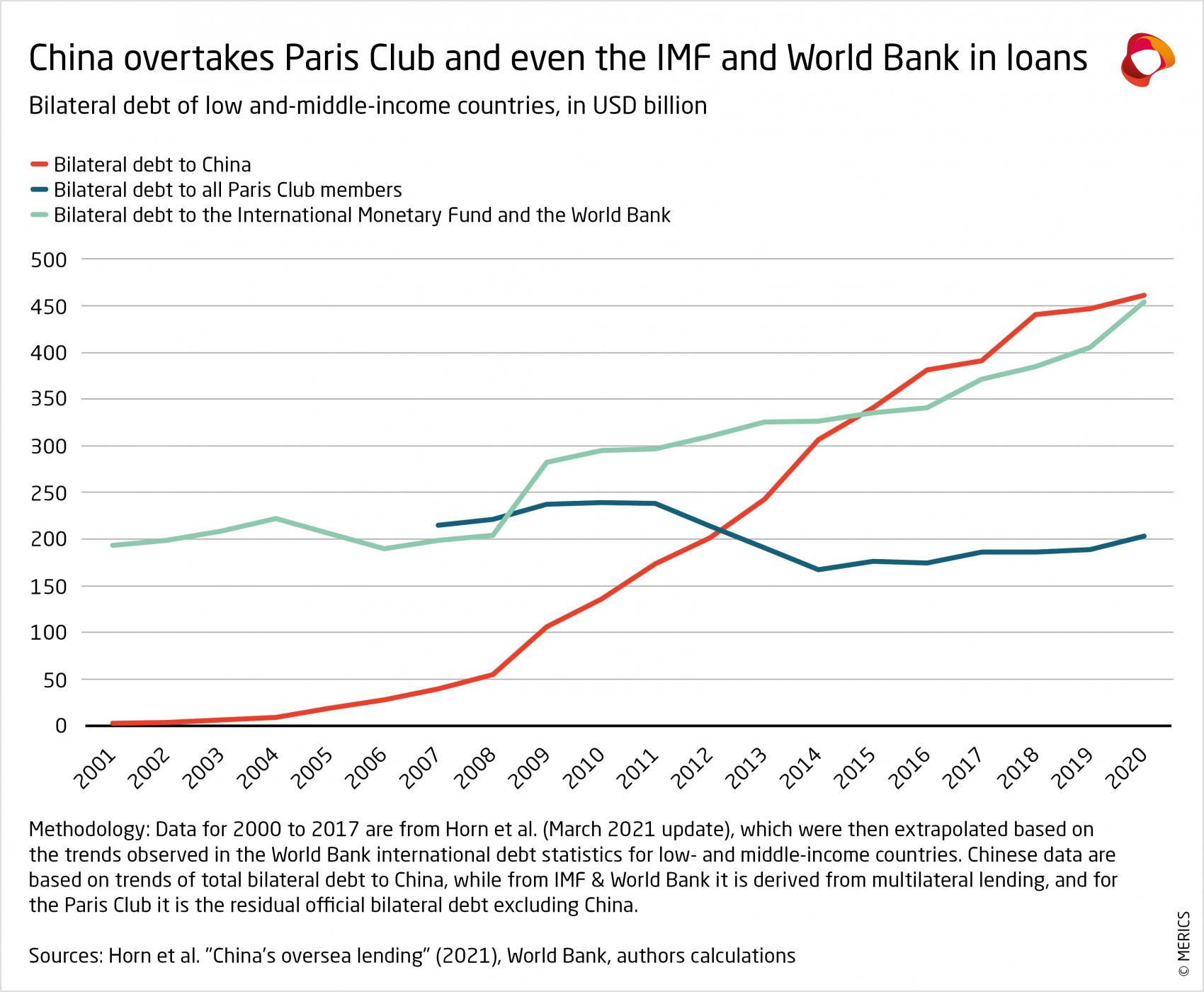

The emphasis on infrastructure-driven investment has also turned China into a major loan provider, providing USD 450 billion in net lending as of 2020 (see Exhibit 21).98 Consistent with its narrative of championing the Global South, most of the lending has gone to developing countries. As a major lender, China can project more financial might, but it is also not risk free. Debt defaults pose a substantial external risk to its financial system.

Case Study: COSCO the embodiment of China, Inc. going global

Jacob Gunter

As a shipping service provider and port operator, COSCO plays a key role in Xi’s international ambitions. The state-owned shipping giant has grown considerably in the last decade and has a truly global footprint.

COSCO is directly managed by the party state and enjoys considerable support in its strategic role

State-ownership: As one of the 97 central SOEs owned and managed by SASAC (which reports to the State Council in Beijing), COSCO is under the direct control of the party-state. While much of the company’s day to day business is done on normal market and commercial terms, it is critical to understand that COSCO does not operate with a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders, but rather with the strategic goals of Beijing in mind.

Protected home market advantage: China allows foreign shipping companies to perform only international shipping services in China, reserving its domestic shipping and transshipping services exclusively for Chinese-flagged vessels owned by Chinese companies. Meanwhile, COSCO can provide all shipping types in Europe, either directly or through local subsidiaries.

Cheap state financing: Research by the Washington, DC, think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) shows that China’s shipping industry benefitted from USD 127 billion in financing from state-run financial institutions in 2010-2018.

Subsidies: The same CSIS report identified at least USD 58 billion in direct subsidies to the shipping industry in 2010-2018.

BRI support: As one of the key players in BRI port projects, COSCO benefits from privileged access to BRI contracts in ports themselves during procurement and thus also cements itself as a partner for corresponding shipping services.

SASAC-directed equity injections: SASAC can coordinate and facilitate the sale of equity between SOEs to raise funds for specific projects – something that could be done in normal financial markets, but which benefits the seller because SASAC makes the political case to purchasers, rather than having to make a case to a market full of potential investors. This happened in 2017, for example, to raise funds for ship purchases (from the SASAC-owned shipbuilding monopoly), when COSCO sold equity to eight other SOEs. Importantly, this can happen the other direction – with COSCO having the burden of being commanded to invest in other SOEs.

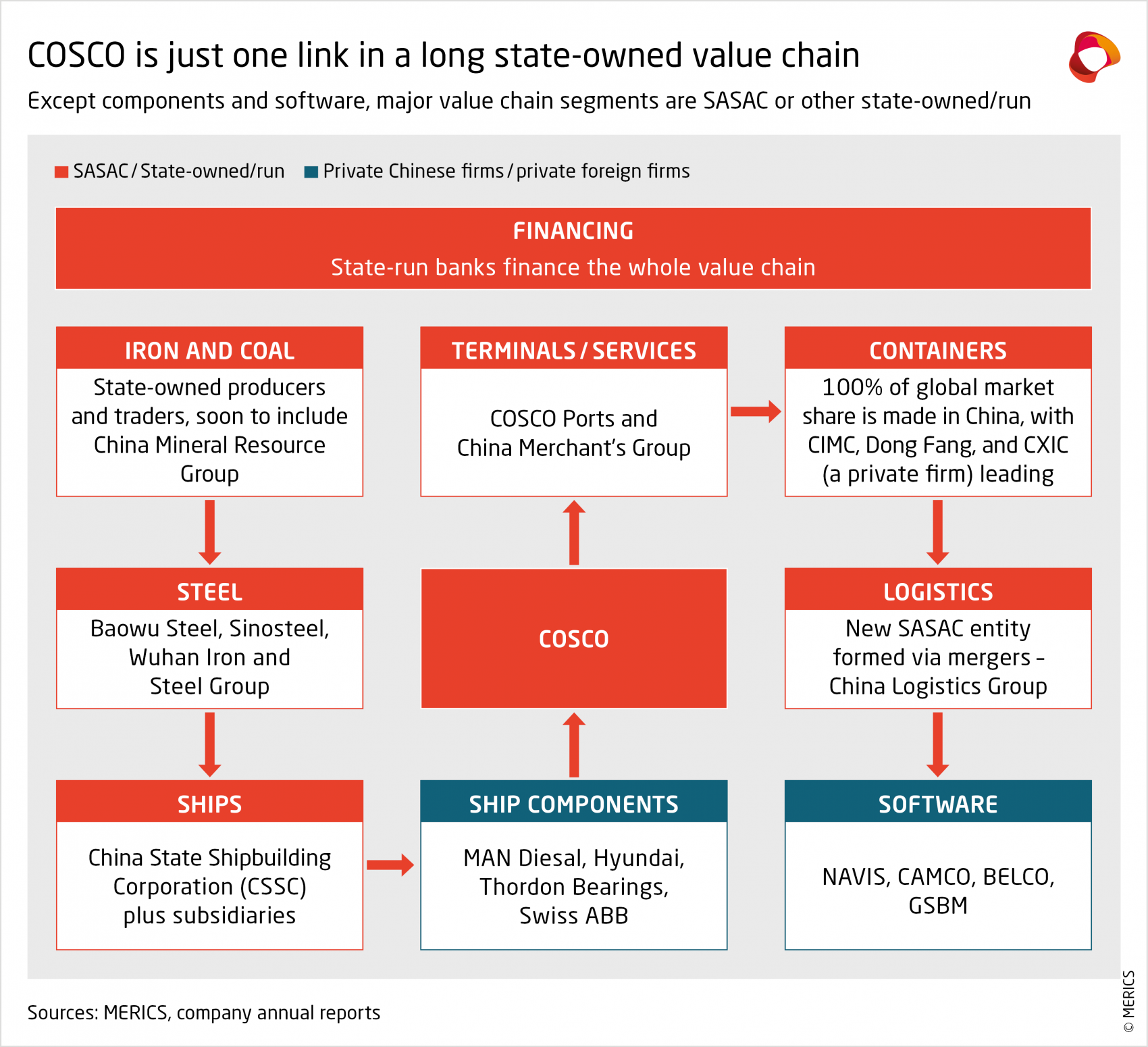

SASAC’s vertically integrated value chain: COSCO is one of the 97 centrally owned SOEs under SASAC – the holding company and manager of those firms. Both upstream and downstream, many of COSCO’s suppliers and customers are state-owned, many specifically SASAC-owned. This opens up possibilities for coordination to pass along subsidies through lower prices from suppliers or higher prices from customers to support COSCO. Importantly, support can be directed to COSCO, but it can also be demanded from it (see Exhibit 22).

Fully aligned with Beijing, COSCO can almost freely advance Xi’s strategic goals

COSCO is a critical player in Beijing’s overseas ambitions and has greatly expanded its fleet as well as its investment footprint in ports all over the world. The company enjoys extensive support in its protected and heavily subsidized home market and has successfully projected the abroad. It can fiercely compete for market share without the same fiduciary responsibility for shareholder returns European shippers face. Importantly, some of COSCO’s port investments and its large footprint in some developing markets are potential avenues for Beijing’s economic coercion toward others, as the sudden divestment or suspension of shipping operations could seriously impact trade. So far, COSCO has advanced Beijing’s interests overseas with little pushback. But the shift in attitudes in the EU from COSCO’s earlier investments in European ports (which were met with little scrutiny) to stronger pushback, for example over a deal in the port of Hamburg, suggests this may be changing.

Case Study: BYD is taking China’s EV revolution overseas

Gregor Sebastian

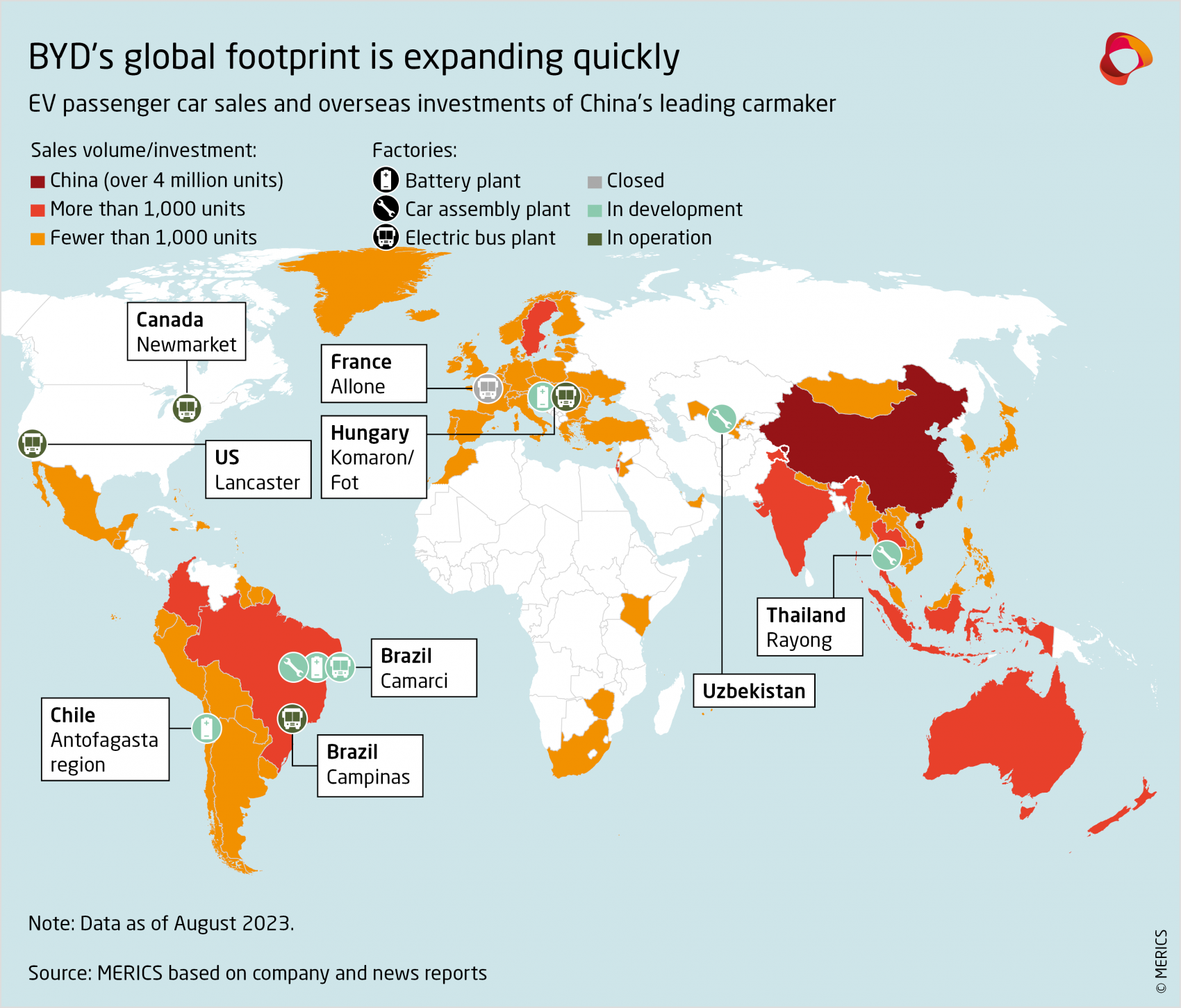

With Beijing’s support, electric vehicle-maker BYD is on a path to become the global industry leader, helping Beijing achieve its long-standing goal of being a manufacturing powerhouse with some of the world’s biggest automotive brands. BYD is deeply integrated in automotive supply chains and is not only assembling components made by suppliers but actually producing high-value components like batteries, IGBT chips and engines. BYD is thus integral to Beijing’s campaign to achieve technological self-reliance and move up global value chains. It also plays a key role in Beijing’s internationalization efforts, going global (along with the whole EV ecosystem), and becoming a high-value export, an investment vehicle in overseas markets, and a technology provider to both developed and developing markets.

BYD benefitted from ample support

Local government protection: Wang Chuanfu has remarked, “without Shenzhen, of course there would be no BYD.”99 Indeed, the local government has not only promoted the rise of BYD through preferential policies such as encouraging research institutes to partner with the firm, but it has also established joint ventures with BYD and designed tailormade subsidies that excluded other carmakers.100 101 102

Protected home market advantage: China shielded Chinese battery makers, including BYD, from overseas competition by making EV purchasing subsidies contingent on the use of battery makers on a whitelist.103 Only Chinese battery makers were on the list before it was discontinued.

Cheap state financing: BYD has repeatedly benefited from credit from state-owned policy banks that often hand out capital to such strategic firms. In 2008, the China Development Bank gave BYD a loan and a year later the Bank of China handed it USD 2.2 billion.104 105

Subsidies: The central government’s purchasing subsidies have enabled BYD’s EV business model – the firm received CNY 32.9 billion in purchasing subsidies in addition to the CNY 5 billion in direct (and publicly known) subsidies to the firm.106 107

Upstream support and state-owned partners: BYD has also benefited from close collaboration with and support from state-owned or state-supported suppliers. Since 2020, the firm has had an R&D collaboration with state-owned steelmaker AnSteel.108 BYD and its subsidiaries such as FAW Fudi New Energy Technology also have several joint ventures with state owned enterprises, potentially further ramping up the firm’s production capacity and R&D capabilities. BYD also benefited indirectly from cheap financing for firms involved in mining and raw material refining necessary for battery production.

BYD’S global footprint suggests success in Beijing’s EV ambitions

Beijing has been very effective in supporting BYD’s rise, which is directly linked to government support. Without Beijing’s protection and nurture, it is unlikely that Chinese car and battery makers like BYD would have thrived as much.

In turn, BYD is also helping Beijing achieve its industrial policy goals. The company is helping China move up global value chains and reduce the country’s reliance on foreign technology, like internal combustion engines, as well as oil imports. What’s more, BYD is helping Beijing gain overseas economic and political influence. The firm is dominating important overseas electric bus markets, for instance in South America, and is now supporting China’s rise as an EV exporter (see Exhibit 23).