Chinese FDI in Europe: 2021 Update

Investments remain on downward trajectory – Focus on venture capital

Key findings

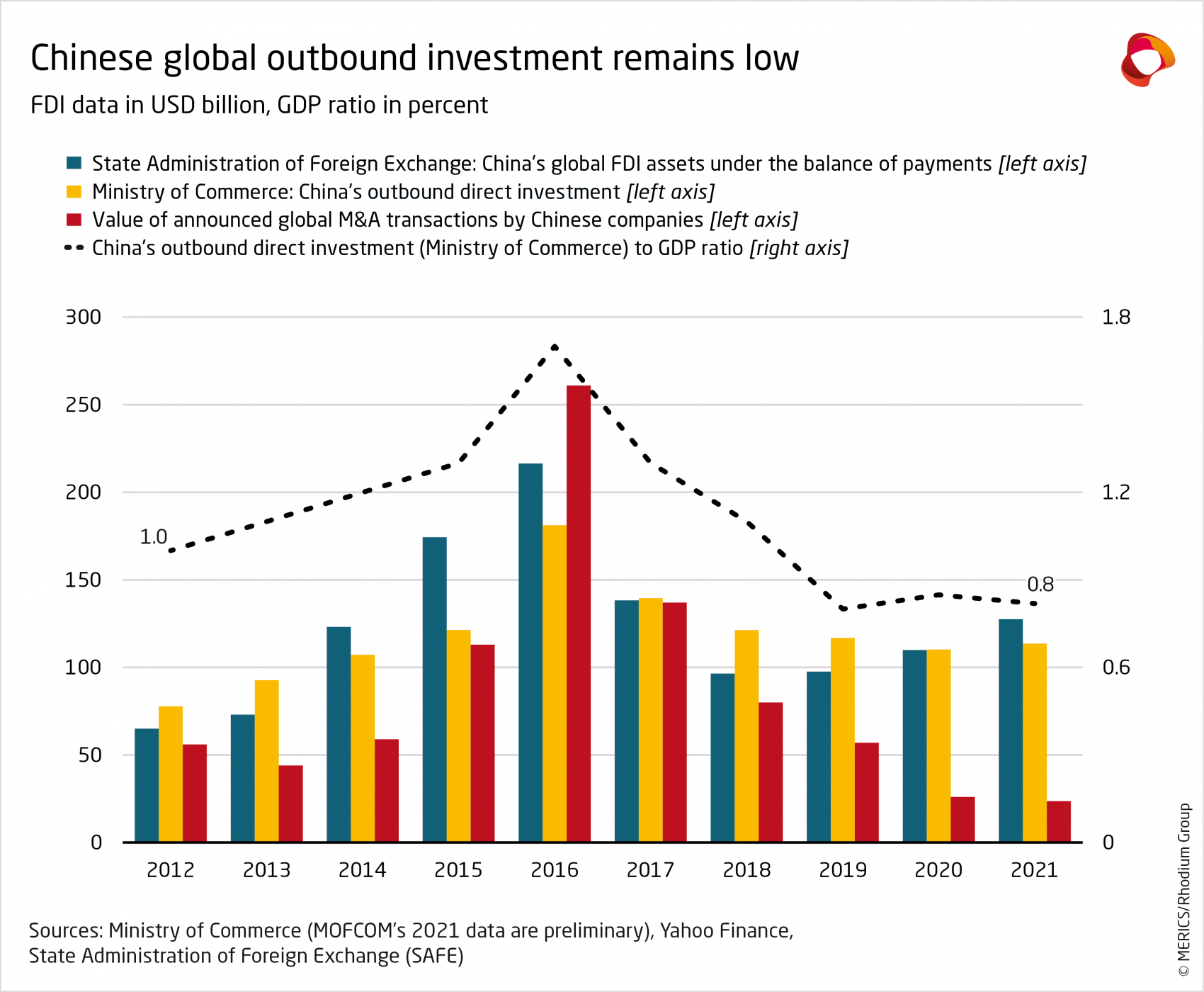

- Chinese outbound investment to the rest of the world stalled in 2021. While overall global FDI rebounded strongly, Chinese outbound FDI edged up by just 3 percent to USD 114 billion (EUR 96 billion). Meanwhile, China’s global outbound M&A activity slipped in 2021 to a 14-year low, with completed M&A transactions totaling just EUR 20 billion, down 22 percent from an already weak 2020.

- China’s FDI in Europe (EU-27 and the UK) increased but remained on its multi-year downward trajectory. Last year, completed Chinese FDI in Europe increased 33 percent to EUR 10.6 billion, from EUR 7.9 billion in 2020. The increase was driven by two factors: a EUR 3.7 billion acquisition of the Philips home appliance business by Hong Kong-based private equity firm Hillhouse Capital and record high greenfield investment of EUR 3.3 billion. Still, 2021 was the second lowest year (above only 2020) for China’s investment in Europe since 2013.

- The Netherlands received most Chinese investment, followed by Germany, France and the UK. Hillhouse Capital’s takeover of the Philips business made the Netherlands the biggest destination for Chinese investment in 2021. Germany, France and the UK accounted for another 39 percent of total Chinese investment.

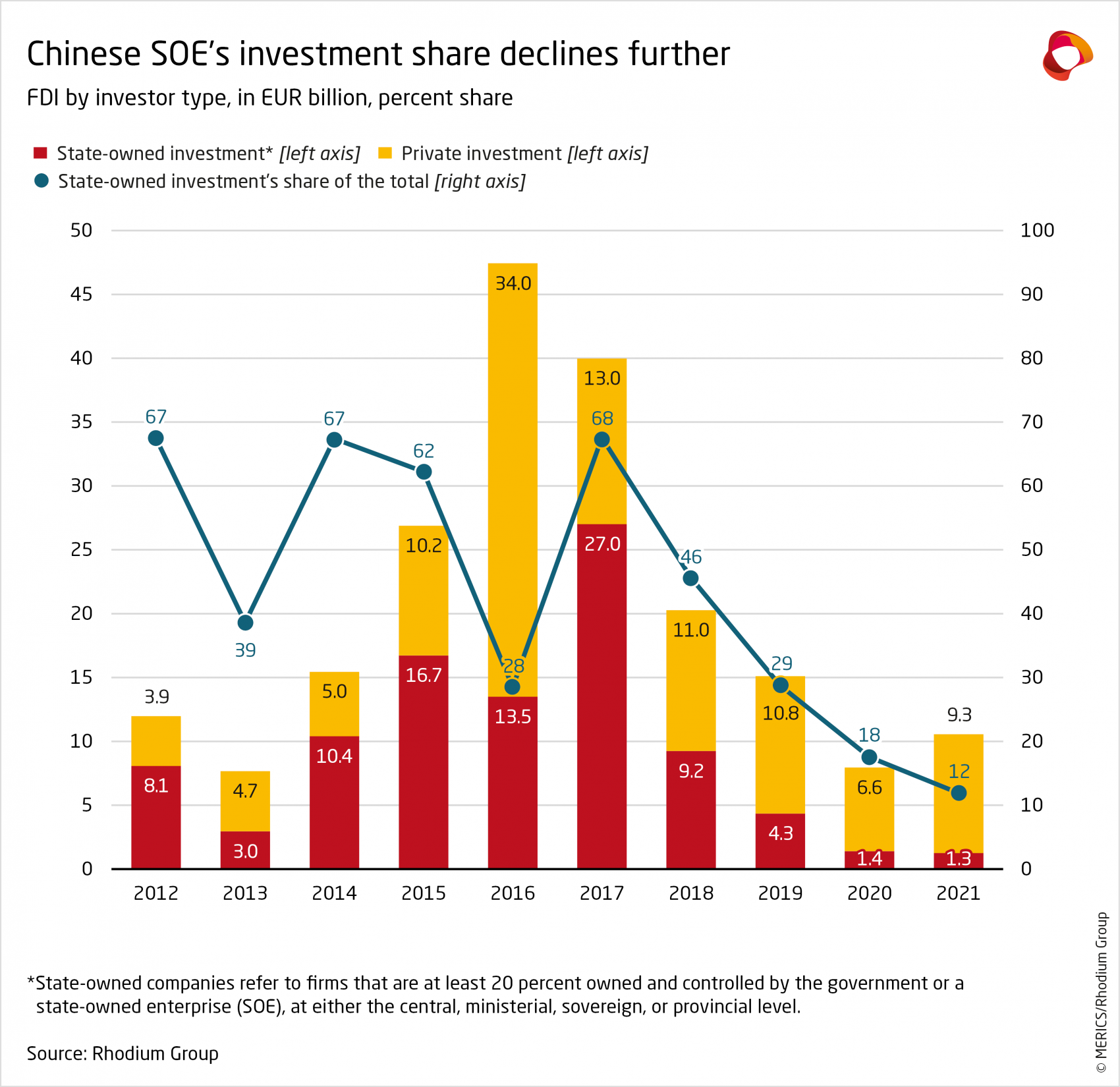

- The share of Chinese state-owned investors fell to a 20-year low in Europe. Compared with 2020, investment by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) decreased by 10 percent. Their share of total Chinese investment also reached its lowest point in 20 years, at 12 percent. SOE investment was concentrated in energy and infrastructure, particularly in southern Europe.

- Consumer products and automotive were the top sectors. Due to the Hillhouse Capital acquisition, investment in consumer products surged to EUR 3.8 billion. Activity in automotive was driven by Chinese greenfield investments in electric vehicle (EV) batteries. Together, the two sectors accounted for 59 percent of total investment value. The next three biggest sectors were health, pharma and biotech; information and communications technology (ICT); and energy.

- The nature of Chinese investment in Europe is changing. After years of being dominated by M&A, Chinese investment in Europe has become more focused on greenfield projects. In 2021, greenfield investment reached EUR 3.3 billion, the highest ever recorded value, making up almost a third of all Chinese FDI.

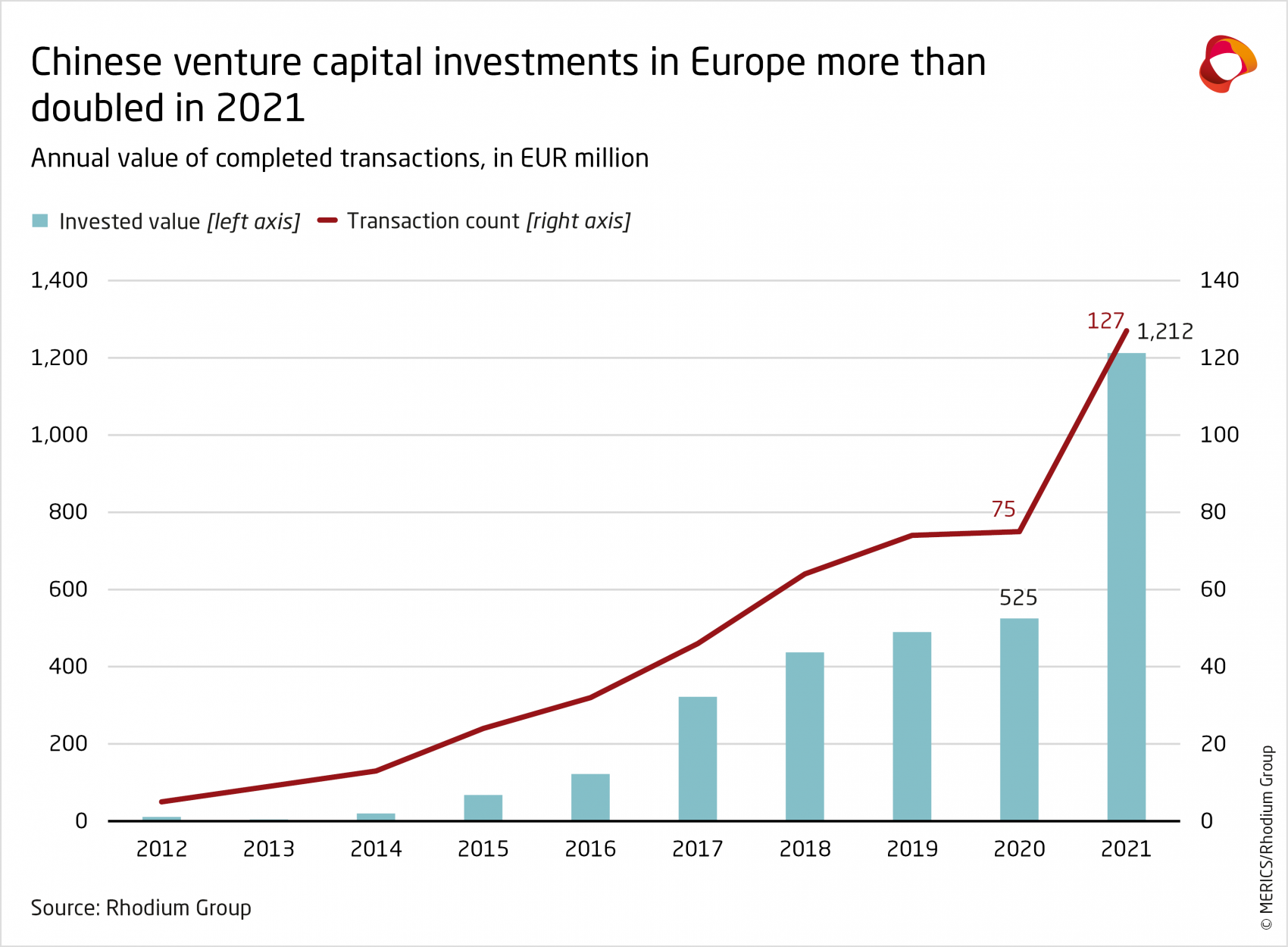

- Chinese venture capital (VC) investment is pouring into European tech start-ups. In 2021, Chinese VC investment in Europe more than doubled to the record level of EUR 1.2 billion. It was concentrated in the UK and Germany, and focused on a handful sectors including e-commerce, fintech, gaming, AI and robotics.

- Chinese investment in Europe is unlikely to rebound in 2022. The Chinese government is expected to stick to strict capital controls, financial deleveraging and Covid-19 restrictions. The war in Ukraine and expanding screening regimes and scrutiny of Chinese investment in the EU and the UK will create additional headwinds.

1. Introduction: China’s outbound investment stalled in 2021

2021 saw a strong global recovery in foreign direct investment flows from exceptionally low levels in 2020. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global direct investment flows rebounded by 77 percent to exceed pre-pandemic levels.

Chinese global investment was an exception to this trend and stalled in 2021. According to official Chinese statistics, China’s outbound non-financial investment increased by 3 percent only in 2021 to USD 114 billion (EUR 96 billion). China’s global outbound M&A activity slipped to a 14-year low in 2021, with completed mergers and acquisitions totaling just EUR 25 billion, down 9 percent from 2020 and 45 percent from 2019.

That China’s global outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) did not recover was due to several factors: China’s overseas investment activity had been declining since 2016, due to domestic constraints on outbound capital flows and tightening scrutiny of Chinese investments abroad.

The lack of a recovery is also likely linked to China’s adherence to a zero-Covid strategy, which hindered cross-border travel and thus deal-making activities. What’s more, sharp competition for global assets in a booming M&A context likely put Chinese buyers at a disadvantage due to their limited international experience and emerging regulatory concerns.

2. Chinese FDI in Europe: 2021 Trends

2.1 Chinese FDI in Europe remained at an 8-year low despite rebound

While China’s global outbound investment did not recover in 2021, Chinese FDI in Europe rebounded, increasing 33 percent from a Covid-induced low point of EUR 7.9 billion in 2020 to EUR 10.6 billion in 2021 (see exhibit 2). The rebound occurred despite continued outbound capital controls in China, pandemic-related travel restrictions, and a now fully operational EU FDI screening regime. However, Chinese investment in Europe remains at very low levels compared to the 2016 high of EUR 47 billion.

Much of the 2021 increase was related to one very large transaction: The Hong Kong-based private equity firm Hillhouse Capital purchased Philips’ home appliances unit. This EUR 3.7 billion acquisition accounted for roughly one third of total Chinese investment in Europe and was the sixth largest ever recorded Chinese investment in Europe. Single large deals like this in an environment of overall low investment volume make it difficult to identify clear, long-lasting trends.

Several other large acquisitions were announced in 2021 but did not go ahead. Gopher Investments shelved a multi-billion EUR bid for the British gambling software developer Playtech (although they still plan to acquire Playtech’s financial trading division in 2022). Tencent saw its planned acquisition of British video game developer Sumo Group stall due to investment screening in the United States (the transaction will go ahead in 2022).

While Chinese M&A grew by 26 percent, accounting for 69 percent of the total (EUR 7.3 billion), it remained below pre-pandemic levels. Greenfield investment was the real surprise, reaching a record high of EUR 3.3 billion (We discuss this development in chapter 3.1).

Exhibit 2

2.2 Hillhouse Capital mega-deal makes the Netherlands the top destination in Europe

The EUR 3.7 billion takeover of Philips’ home appliance business by Hillhouse Capital made the Netherlands (and, incidentally, the Benelux) the top destination for Chinese investment in 2021, accounting for 35 percent of the total. Chinese investment, particularly greenfield investment in the automotive and ICT sectors, was also strong in Germany, France and the United Kingdom. The “Big Three” economies jointly accounted for 39 percent of the total. This was driven by a recovery in Chinese investment in the UK, from a ten year low of EUR 1.4 billion in 2020 to EUR 2.1 billion in 2021. In contrast, investment in France and Germany dropped from EUR 872 million in 2020 to EUR 509 million, and from EUR 2 billion to EUR 1.5 billion (the lowest value since 2015) respectively.

Investment in Southern Europe (EUR 1 billion) increased by 36 percent, propelled by Chinese state-owned enterprise investments in Spain’s energy sector (EUR 600 million). Investment in Eastern Europe (EUR 385 million) decreased 74 percent, after a strong run in 2020 due to one large acquisition in Poland.

Investment in Northern Europe remained stable at EUR 1.2 billion, on the back of strong Chinese investment in Finland (at EUR 891 million). The biggest deal in the region was Shenzhen Mindray’s purchase of Hytest Invest OY, a Finnish medical device maker, for EUR 560 million. Albeit at a low level, Chinese investment in Ireland (EUR 238 million) reached its second highest value ever, primarily due to ByteDance’s (Tiktok) ongoing investments in a local data center.

Exhibit 3

Exhibit 4

2.3 Investment share of China’s state-owned companies drops to 20-year low

Solidifying a four-year trend, private companies continued to dominate Chinese investment in Europe in 2021. At EUR 9.3 billion, their investments accounted for 88 percent of the total, compared to an already high 83 percent share in 2020. Investments by state-owned companies decreased by 10 percent in volume, from EUR 1.4 billion in 2020 to EUR 1.3 billion in 2021. Their 12 percent share of total investment was the lowest since 2001.

State-owned enterprises remained focused on acquisitions. Their biggest deals were concentrated on energy and infrastructure sectors in Southern Europe. In Spain, the power company China Three Gorges purchased renewable energy assets for over EUR 500 million (and already announced plans to purchase a Spanish wind park portfolio for EUR 305 million in 2022).

In Greece, shipping conglomerate COSCO acquired additional shares in the port of Piraeus for EUR 128 million, bringing its ownership up to 67 percent overall. That acquisition came as part of an agreement that required COSCO to also invest EUR 294 million as greenfield investment to upgrade the port’s terminals. Even though COSCO has only invested about a third of that sum to date, the acquisition was allowed to go ahead.

In Portugal, China Communications Construction Company bought 23 percent of Mota-Engil Group – the country’s largest public works group with business in Latin America, Africa and Eastern Europe – for EUR 171 million.

2.4 Bulk of investment concentrated on consumer goods and automotive

In terms of sectors, the Hillhouse Capital deal pushed consumer products and services (EUR 3.8 billion) to the top, with 36 percent of the total. Automotive (EUR 2.4 billion) came in second, accounting for 23 percent of all Chinese investments.

While Automotive has long been a key sector for Chinese investment in Europe, this year was different in two ways: most of that investment took the form of greenfield projects, instead of acquisitions as in previous years; and most of that investment went to support the new energy vehicle industry, via battery factories (instead of investments in traditional internal combustion engine technologies). The trend could continue next year. According to news reports, CATL is scouting locations for a second European battery plant, worth EUR 2 billion, in Poland. CATL’s first one in Germany is to commence production in 2022.

Chinese companies also displayed strong interest in health, pharmaceutical and biotech, with EUR 961 million in investment in 2021, and ICT, with EUR 941 million. The two sectors accounted for 9 and 8 percent of total investment respectively. Major deals included Shenzhen Mindray’s acquisition of medical device maker Hytest Invest for EUR 560 million as well as Huawei’s and ByteDance’s continued investment in greenfield projects in Ireland and the UK.

Exhibit 6

3. More greenfield, more venture capital - more scrutiny

3.1 Greenfield becomes a major form of Chinese investment in Europe

M&A transactions have dominated Chinese investment in Europe over the past two decades, but over the last two years, greenfield investment has seen a rapid increase. In 2021, it reached EUR 3.3 billion, up 51 percent from 2020 levels and standing at more than 240 percent the average level of Chinese greenfield investment in the EU between 2015 and 2019 (see exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7

This increase was driven by a handful of large deals in automotive and ICT: SVOLT Energy’s and CATL’s EV battery plants in Germany, Envision AESC’s EV battery plants in France and the UK, ByteDance’s data center in Ireland and Huawei’s optoelectronics R&D center in the UK. As such, it does not yet constitute a solid, multi-year trend across many players or sectors. Yet, with now over a third of China’s FDI to Europe going to greenfield projects, China’s footprint in Europe is now looking quite different from the past.

This shift towards greenfield investment is likely shaped by several factors:

- Chinese firms exploring overseas opportunities: Companies such as CATL, which thanks to its dominant position in China now commands 32.6 percent of the global EV battery market, are looking to escape a crowded and increasingly mature home market and tap into attractive overseas opportunities and diversify their business. Firms like Tiktok have also built internationally successful brands and are investing to roll them out in high-growth destinations.

- A need to integrate into European supply chains: Chinese greenfield investments are also fueled by the need for a local presence in certain sectors. Batteries, for instance, are costly to ship, so OEMs have a high incentive to build local battery plants to serve growing European EV production capacity.

- Compliance with EU regulations: In the ICT sector, players like ByteDance are facing stringent local regulations (including GDPR) and hence need to invest in local capacity to ensure that such regulation is respected (e.g., that user data is stored in Europe).

- Tapping into Europe’s innovation system: Greenfield investments can become a new avenue for technology acquisition. Huawei’s research and development center (R&D) and CATL’s battery plant – which also includes R&D facilities – will be used as springboards to tap into Europe’s innovation system and skilled workforce. Both have announced plans to use their investments to enter into R&D collaborations with European research institutes, universities and local industry.

- Avoiding regulatory hurdles: Greenfield investment is typically subject to fewer screening measures by national governments and tends to be more welcome locally – for example, as a channel to create local jobs and contribute to local tax revenue.

The rise in Chinese greenfield investment in Europe is a reflection of global trends. China’s global footprint has shifted more towards greenfield projects over the past couple of years.

This may be most potent in the NEV sector: In Asia, Envision AESC is building a battery plant in Japan for EUR 387 million and a Chinese consortium that includes CATL plans to invest EUR 4.2 billion in an Indonesian lithium battery plant. In the US, Envision AESC has announced plans to build a battery plant to supply Mercedes-Benz. CATL is also scouting for a location for a battery plant in North America worth up to EUR 4.5 billion.

In short, Chinese firms are now investing heavily in global production sites, compared to their historical focus on asset and company acquisitions.

3.2 Chinese venture capital investment in Europe more than doubles

2021 also saw pronounced growth in Chinese venture capital investment in Europe, in line with Europe’s total VC investment growth, which increased by 120 percent to just over EUR 100 billion. Levels of Chinese VC investment more than doubled in 2021, to EUR 1.2 billion. These remain way below levels of China’s VC investment in the United States, which stood at EUR 2.9 billion in 2021, but marked a sharp uptick.

These investments were strongly concentrated on a handful of countries. Half went to Germany (EUR 597 million), followed by the UK (EUR 230 million) and then Sweden (EUR 121 million).

Quite predictably, investments focused on high-tech start-ups in rapidly growing sectors. Top transactions included Tencent’s participation in funding rounds for German B2B payment provider Billie (for an estimated EUR 166 million) and for German on-demand grocery deliverer Gorillas (for EUR 158 million).

The Chinese wealth fund CIC Capital also contributed EUR 99 million of a EUR 2.3 billion funding round for Swedish EV battery maker Northvolt. Chinese VC investment in the UK was characterized by a large number of small transactions. The biggest included Tencent’s EUR 50 million investment in medtech company CMR Surgical and Ping An Insurance’s EUR 38 million investment in 10x Future Technologies Services.

The uptick in China’s VC investment in Europe was likely also influenced China’s tech and industrial policies of 2021. Last year, Beijing cracked down heavily on edtech, crypto and gaming as well as big tech giants more generally, which curtailed domestic opportunities and likely pushed Chinese investors to pursue VC opportunities abroad (such as Hillhouse Capital’s investment in French gaming firm Sorare SAS for EUR 38 million).

At the same time, Beijing’s promotion of sectors like robotics and medtech might have encouraged related VC investment overseas. Several Chinese investors in fact poured capital into Sino-German start-up Agile Robotics.

The rise in China’s VC investment in Europe might finally be explained by comparatively low levels of scrutiny around VC flows in Europe (compared to M&A and greenfield FDI). In contrast to large acquisitions, small VC deals might fly under the radar due to the speed of deal making, level of technological complexity, and often limited shareholding taken (below 10 percent).

The United States started screening certain VC investments in 2018 and, in 2020, India restricted incoming Chinese investment, including venture capital. The EU’s investment screening regulation allows member states to screen below the 10 percent threshold, but many member states still need to implement such guidance into their own mechanism and screening practices.

3.3 European countries continue to tighten investment screening regimes

The EU investment screening regulation, in force since October 2020, has contributed to increased scrutiny of foreign investment and incentivized the creation of screening regimes across Europe. Of the 27 EU member states, 18 now have legislation in place that allows them to screen foreign investments (up from 11 in 2017), and all but three member states are planning to establish or amend screening regimes.

From October 2020 to June 2021, as part of their duties under the new EU FDI regulation, 11 member states notified 265 transactions as potentially problematic to the EU, of which eight percent concerned investors ultimately from China.

Most publicly known cases of reviewed Chinese investments focused on critical infrastructure and strategic dual-use technologies (see exhibit 9). Several screenings involved acquisitions of semiconductors producers, an area in which China wants to become independent from foreign suppliers. Italy blocked two acquisitions in the sector. At the time of writing, the acquisition of Elmos Semiconductors production lines by SAI MicroElectronics in Germany and the takeover of Newport Wafer Fab by Chinese-owned Nexperia in the UK were still under review.

Exhibit 9

Among highly publicized cases in 2021 was the review by the Italian government of the 2018 takeover of Italian drone maker Alpi Aviation. The case is a good illustration of the importance, yet also the limitations, of investment screening mechanisms. Alpi Aviation was acquired, through several intermediaries, by a consortium made up of CRRC and an investment group controlled by the Wuxi city government. At the time of the transactions, the buyers failed to notify the Italian authorities despite legal requirements to do so.

The case came under public scrutiny in September 2021, amidst news that the government was probing the deal over an alleged breach of the rules on sales of military materials. The sensitive nature of the transaction highlights the usefulness of screening mechanisms to avoid dual-use knowledge being transferred across borders. However, screening mechanisms might not always be effective in catching smaller deals like the Alpi one, which can end up escaping regulatory scrutiny.

4. Outlook: Era of massive Chinese investment seems over for now

In 2022, we expect China’s FDI flows into the EU to remain at the current low levels. Existing constraints on Chinese outbound investments remain in place, and new ones have emerged. This does not preclude the possibility of another investment uptick in 2022: current low investment volumes make it difficult to identify clear trends, and any single large deal could translate into sizeable changes in China’s investment level or structure (by country, sector, ownership or type). The era of massive Chinese investment in Europe seems over for now.

The most important factors that will shape Chinese investment flows to Europe in 2022 are:

In China:

- Tight capital controls: China’s capital controls, a key driver of the decline in Chinese global outbound FDI since 2016, are unlikely to be relaxed in 2022. Instead, China’s leadership will prioritize stability in the run-up to the 20th Party Congress (inclusive of economic and capital flow stability), especially at a time of slowing economic growth.

- Zero-Covid policies: Strict Covid-19 containment policies continue to complicate China’s economic engagement with the outside world. With the significant uptick in Covid-19 infections in China, international travel restrictions are likely to remain in place for much of 2022. This will keep the pace of deal-making down and hinder due diligence processes.

- Lower growth: Slowing growth in China could, however, make overseas investment more attractive in certain sectors. Companies in slowing sectors in China, facing strong domestic competition, might be encouraged to go abroad in search of new market opportunities.

- China’s tech policies: China will likely continue to crack down on certain parts of its tech sector, particularly consumer and other digital technologies. Combined with Europe’s openness to Chinese VC investments, this could lead to continued high VC interest in the region.

In the EU:

- Ramped up regulatory scrutiny of FDI: Eight EU member states are planning to develop or amend their investment screening regimes in 2022, and in January, the UK enacted the National Security and Investment Act. These moves could further increase scrutiny of inbound Chinese investment. The EU is also moving ahead with various new regulations – on procurement, foreign subsidies, supply chain due diligence and anti-coercion – that could impact market access for Chinese companies in Europe and diminish appetite for investment.

- EU-China tensions: Tensions in the EU-China relationship following tit-for-tat sanctions in March 2021 and Beijing’s imposition of a trade embargo on Lithuania in December 2021 are likely to continue to weigh on bilateral ties in 2022. With Chinese sanctions on EU lawmakers in place, the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) is likely to remain on ice through 2022.

- Geopolitical impact of the war in Ukraine: The exact impact of the war in Ukraine on China’s investment will depend on the development of the crisis and the stance the Chinese government ends up taking towards the conflict. However, the war has already triggered intense debates on critical infrastructure and resilience in Europe, which could in turn increase scrutiny of Chinese investment in a number of sectors including infrastructure, transport and energy.