The EU sees early successes in using foreign subsidy regulation against Chinese companies

Beijing’s concerns about the EU’s Foreign Subsidies Regulation show that the block is addressing distortions caused by Chinese state subsidies. However, Andreas Mischer says that further steps may still be necessary.

China is keen to present itself as a responsible global actor in the trade war with the United States, ignoring the fact that it has in recent years strained its relationship with the EU by prioritizing its own interests over those of its partner. The EU in 2016 worried about the loss of strategic technologies when China’s Midea took over German robotics company Kuka, was incensed in 2021 when China implemented a de-facto trade embargo against Lithuania after perceived transgressions against its “One China” policy in 2021, and it now fears that the export of cheap and heavily subsidized overcapacity from China will threaten European industry.

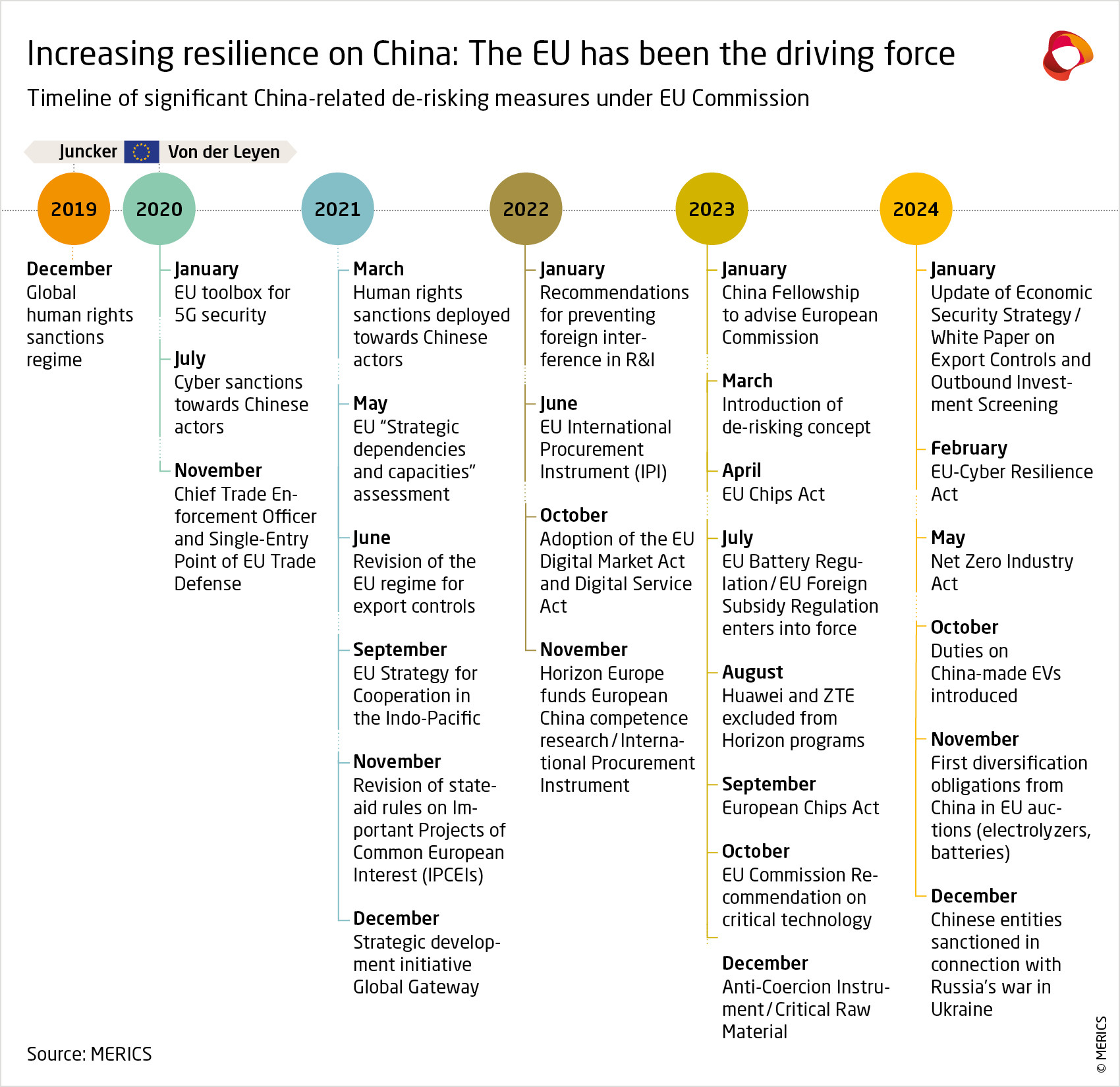

In response, the European Union has adapted and expanded its policies for responding to economic threats caused by geopolitical uncertainties in general and the challenges posed by China in particular. In 2023, the European Commission announced a European economic security strategy. That same year, the EU’s new anti-coercion Instrument, aimed at countering economic pressure from other countries, and its Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), designed to address market distortions, came into force. A year later, the Commission proposed a revision of the FDI screening regulation to enhance scrutiny of foreign direct investments.

Brussels now has unprecedented power to address market-distorting foreign subsidies

Among these measures, the FSR deserves more attention, as it gave the EU unprecedented powers to address market distortions caused by subsidized foreign companies operating within the single market – where previously only subsidies from EU governments had been subject to scrutiny. Under the new rules, companies have to notify the Commission of foreign financial contributions relating to planned mergers, acquisitions or bids for public contracts. In addition, Brussels can launch investigations of its own accord and has far-reaching powers to impose fines, order the divestment of assets or even block transactions.

Since 2024, the Commission has applied the FSR in several cases involving Chinese companies:

- Railways: Brussels launched its first investigation after being notified by CRRC Qingdao Sifang Locomotive Co. of its intention to bid in a public procurement tender issued by Bulgaria’s Ministry of Transport and Communications. CRRC then scrapped its plans.

- Wind turbines: The Commission is conducting a so-called ex officio investigation into Chinese wind turbine suppliers after reports that they had won orders related to the expansion of wind farms in member states including Bulgaria, France and Greece.

- Security inspection equipment: An unannounced inspection targeted offices of Nuctech, a Chinese state-owned company supplying security equipment, in Poland and the Netherlands. The European Court of Justice rejected legal appeals by Nuctech.

- Electric vehicles: In March 2025, Brussels launched an inquiry into BYD, a Chinese electric vehicle maker, to investigate whether subsidies from the Chinese government for the construction of a production plant would distort competition.

China has complained about the FSR, without moderating its approach

By that point, Beijing had already expressed concerns about the FSR. China’s Ministry of Commerce in January 2025 concluded a six-month investigation into the regulation by accusing the EU of selectively targeting Chinese companies, using an ambiguous definition of foreign subsidies, and creating unnecessary uncertainty and onerous reporting requirements for companies. The Chinese government’s misgivings indicate that the FSR is having some initial success in countering the distorting effect of Chinese state subsidies on the EU single market.

By applying the FSR, the EU has demonstrated its increasing determination to protect its internal market and economic security against foreign interference. However, its trade and competition policy instruments, including the FSR, have been based on market principles and have mainly been used to defend against market distorting behavior by foreign actors. In the long run, these reactive measures may not provide the same level of protection bestowed by China’s more aggressive approach – one the US seems increasingly keen to adopt, too.

The EU may need to reach beyond the instruments of trade and competition policy to adopt a more forceful industrial policy that centralizes decision-making in Brussels. Member states currently control many more subsidies to steer national industrial policy goals than the EU controls to steer European ones. This creates the risk of bidding wars between member states to attract foreign investment – and of China focusing on bilateral relations at the expense of the EU as a whole. Ultimately, the EU may have to move towards China’s more protectionist, industrial policy-focused model to protect its economy and economic sovereignty.