How Europe is throwing the strategic communication game with China and how it could go all in

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

European capitals are giving Beijing too much leeway to shape public perceptions of bilateral diplomatic exchanges, says Grzegorz Stec. There are several steps European countries can take to make their messages clearer and more forceful.

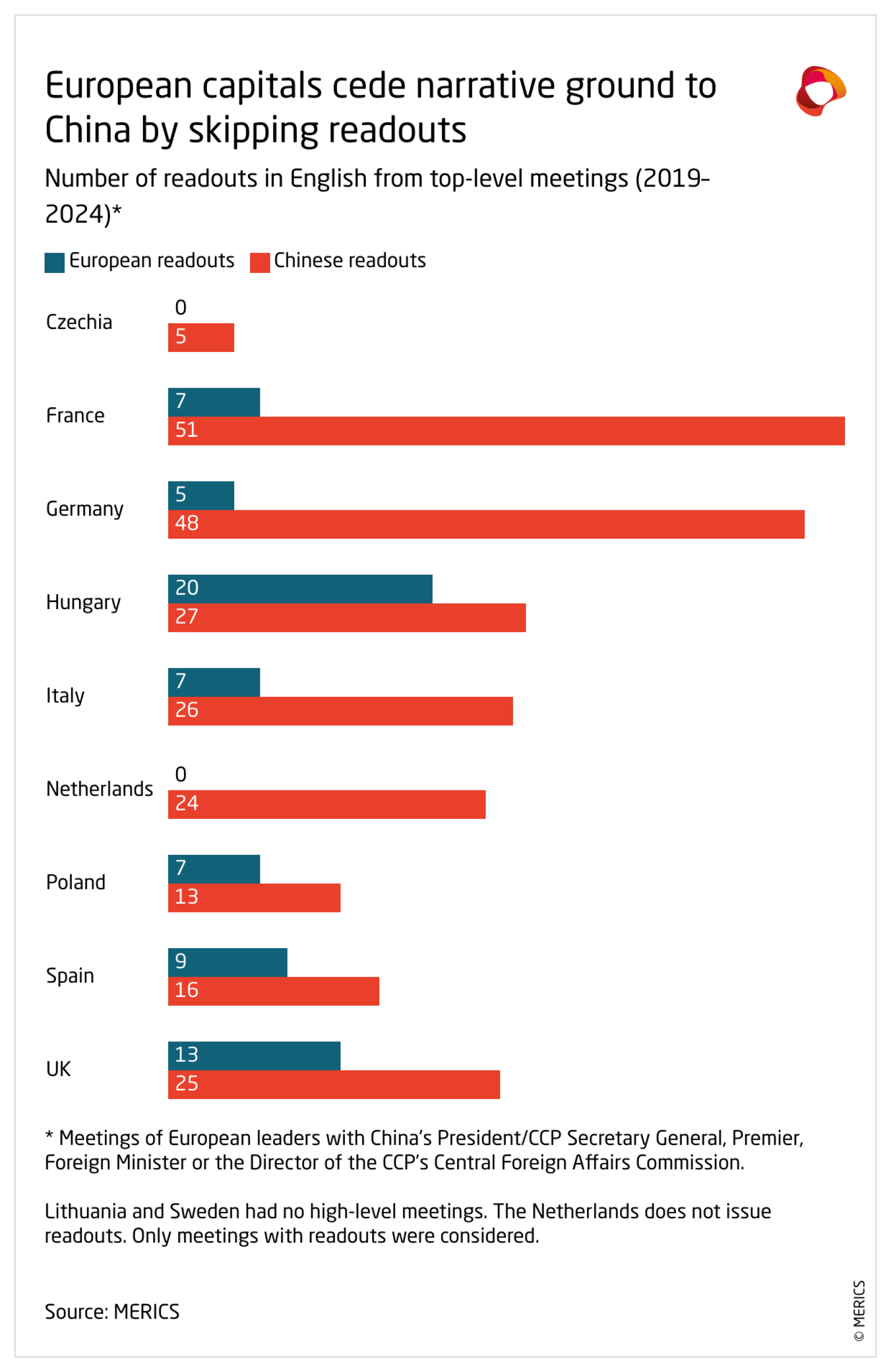

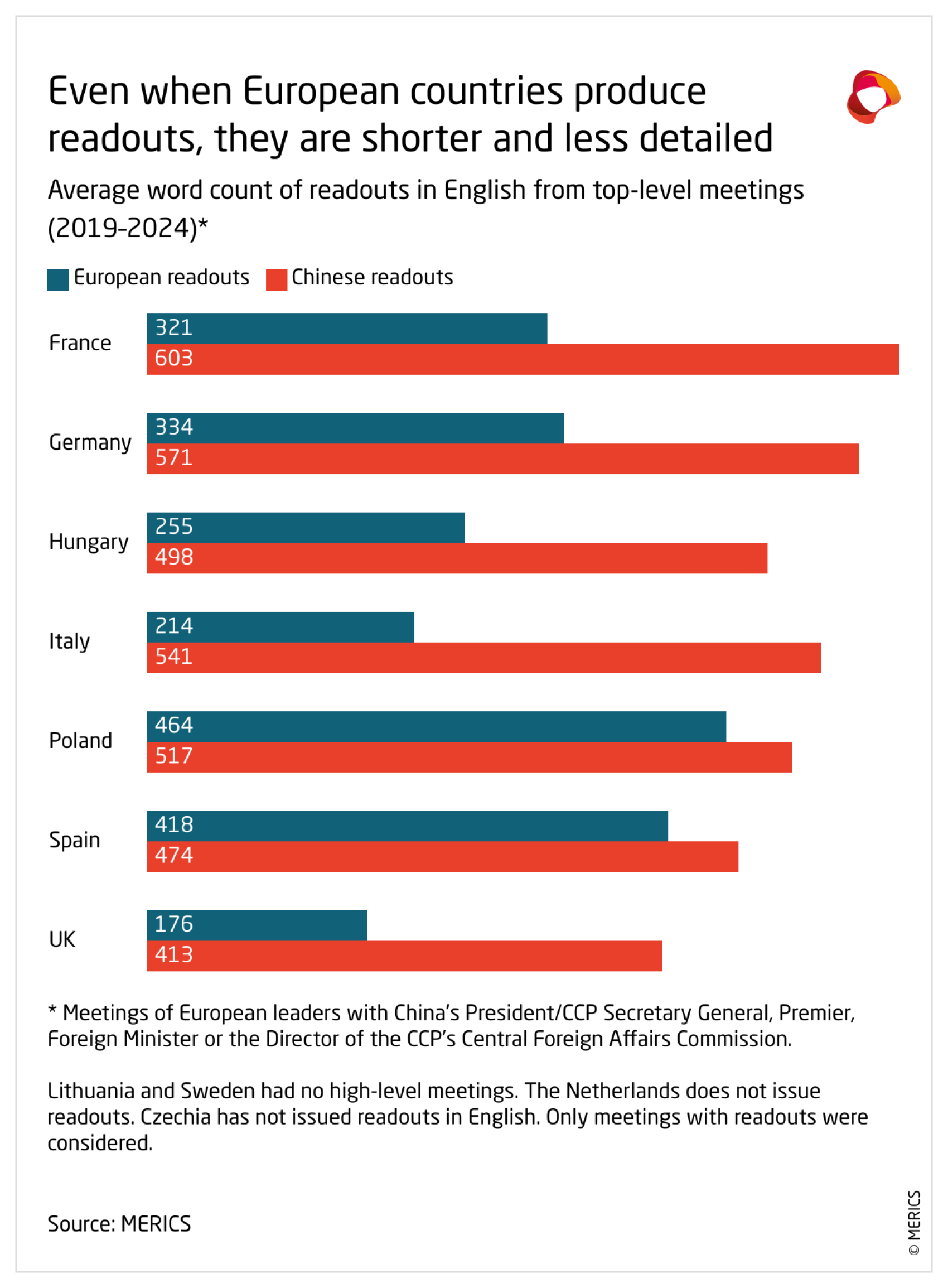

European capitals are giving Beijing too much leeway to shape public perceptions of bilateral diplomatic exchanges. MERICS has analyzed readouts issued by governments after their leaders engaged with Chinese counterparts between 2019 and 2024: less than 40 percent of China’s official summaries in English were matched by an English-language communication from the European side – and even when they were, European readouts were on average 40 percent shorter and much less detailed. This shows that European Union (EU) member states are not taking the competition to shape the narrative of EU-China relations seriously enough.

Beijing is extremely adept at and forthright about controlling its image, promoting Chinese concepts, and (re)framing European positions to suit its own purposes in order to enhance its “international discourse power“ (国际话语权) and “tell China’s story well“ (讲好中国故事). Donald Trump’s return to the White House and the ensuing geopolitical turmoil have heightened transatlantic tensions and have made it easier for Beijing to project a benevolent stance towards the EU and its members in contrast to a more aggressive Washington.

In an attempt to weaken the traditional transatlantic partnership and promote an EU-China rapprochement, China has for several years been trying to reframe the European concept of “strategic autonomy” as essentially anti-American.

In similar vein, Beijing is trying to leverage the tensions in transatlantic relations to contrast itself with Washington primarily through diplomatic messaging affecting the calculus in European capitals. At the Munich Security Conference in February, Foreign Minister Wang Yi praised the prospects for cooperation with Europe to stabilize the multilateral order and called for European involvement in any peace talks to conclude Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He met with EU High Representative Kaja Kallas, Germany’s former Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the foreign ministers of France, Germany and Spain. Yet only the EU and the French government released readouts to complement the many issued by Beijing.

Subsequent media coverage focused on a perceived EU-China rapprochement, ignoring the many thorny issues that still divide the two sides – most immediately, China’s support for Russia in its war against Ukraine. The fact that many European governments regularly forego the opportunity to use readouts to tell their story well is a stark illustration of how they leave China huge opportunities present its take on events as seemingly uncontested and therefore acceptable. They need to make use of readouts more rigorously to communicate their motivations and perspectives to the people, governments and other partners in and outside of Europe.

Why readouts matter – Information control at time of uncertainty

In the absence of timely or comprehensive European alternatives, the media often refer to Chinese readouts, presenting the European public with unchallenged Chinese narratives. This can create a disconnect, as Chinese-inspired upbeat coverage of high-level meetings clashed with the European media’s day-to-day reporting of policy debates about the strategic risks associated with China. This makes it harder for European leaders to explain the need for an assertive and not seldom costly China policy, as in the case of imposing additional import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles or blocking specific Chinese investments.

It also makes it more difficult for European leaders to talk to each other. As many member states do not regularly brief each other or the EU level on their exchanges with Chinese counterparts, other European governments use readouts as the first means of building a picture of another government’s bilateral exchanges. Moreover, unchallenged Chinese narratives leave room for Beijing to try to intensify competition among European countries for favorable relations. Ultimately, this supports China’s strategic efforts to weaken the European Union’s China policy by dividing member states in their approaches to dealing with Beijing.

Similar risks of miscommunication exist when it comes to Europe communicating with its partners, including the US and countries in the Global South – the latter in particular not having an easy access to official European versions of exchanges with China. Miscommunication can be diplomatically costly especially at time of heightened tensions and a more personalistic foreign policy in Washington. A stark recent example of Beijing’s agility is the Chinese readout from a China-Japan-Korea trade ministers' meeting – held three days before Trump’s “Liberation Day” speech – which sparked international headlines that “China, Japan, South Korea will jointly respond to US tariffs.” The statement got rebuffed by Seoul as exaggerated and by Tokyo as untrue.

Readouts stand for a broader strategic communication challenge

At a time of great geopolitical uncertainty, European governments must coordinate their positions better than ever before, speak with one strong, credible voice to keep foreign partners in line, and convince the European public of the need to pay a security premium they have not had to shoulder since the end of the Cold War. (Without public readiness, leaders are constrained, as MERICS’ Europe-China Resilience Audit made clear.) Effective communication is a prerequisite for this – and readouts are just the tip of the iceberg. Three things currently limit Europe’s ability to win the “strategic communication game” with China.

Limited EU alignment

Europe’s bargaining power, credibility and deterrence are undermined by inconsistent messages from European leaders – both in what they say and what they do not say. Time and again, European leaders make statements during visits to China that do not align with the EU’s positions as a bloc. For example, French President Emmanuel Macron said Europe should not be drawn into a great-power conflict over Taiwan as a “follower” pushed by “the American rhythm or a Chinese overreaction” while he was finishing his China visit in April 2023, Polish President Andrzej Duda was reluctant to clearly address in public statements Beijing’s support for Russia in June 2024, and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez called China a "defender of peace" a few months later.

No national clarity

Most EU member states still do not have a dedicated China strategy or guidelines for their bilateral approach. Of the 11 countries analyzed in MERICS’ EU-China Resilience Audit, only Germany has a declared strategy, published in July 2023, while the Netherlands released a policy paper in May 2019, and Sweden a government communication in September 2019. A few have followed the lead of the UK; a non-member, to assess their China strategies through parliamentary panels or the Netherlands with dedicated multiministerial parliamentary hearings on China policy. But most member states have shied away from such public determinations, hindering coordination and agreement within and between governments as well as with business and civil society.

This suggests that limited EU alignment is as much the result of unclear national positions towards China as it is of entrenched opposing views within Europe. Consistent EU messaging is most fundamentally based on clear national policy objectives – which is why the governments of all member states should set about formulating them. They would benefit from conducting internal exercises to develop a national assessment of their long-term objectives and priorities to guide policy towards China. This process should include government engagement with business and other key national stakeholders.

Deficient defenses

European governments also need to respond to the risk of information manipulation and interference by China. The EU has since 2018 been developing its capacity to respond to foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) operations, though their primary focus remains Russia. In addition, all EU member states participate in the Rapid Alert System to report instances of FIMI. However, national units responsible for tackling disinformation tend to be located within foreign ministries, but as MERICS’ Resilience Audit research showed, their responsibilities can also be spread across ministries and agencies, complicating coordination.

As a result, responding to China-related FIMI remains a challenge, as national FIMI response units continue to focus on Russia, and China-related capacity remains comparatively limited. None of the 11 countries analyzed in MERICS’ EU-China Resilience Audit require the labelling of news from foreign state-affiliated media outlets – and four out of the 11 countries' national news agencies maintain content sharing agreements with China’s official state news agency, Xinhua. In addition, by reaching almost a third of the population in the countries analyzed, TikTok also poses a potential risk that information consumed by many European could be manipulated as highlighted by EU’s investigation into TikTok’s role in Romanian elections controversies.

Recommendations for the way forward

Europe urgently needs to strengthen its strategic communication with and about China. With European capitals likely to combine any renewed push for engagement with continued de-risking and addressing structural economic tensions, the risk of mixed signals is high. Fortunately, improving communication is often more about adjusting existing practices than committing financial resources. It’s about making strategic communication on China part of the relation’s management process, not an afterthought or an add-on.

There are several steps European countries can take to make their messages clearer and more forceful. Each needs to:

- Define a long-term approach to China, with clear public messaging – in the form of fully-fledged government guidelines or major policy speeches, as demonstrated by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, James Cleverly when he was UK Foreign Secretary and Annalena Baerbock when she was German Foreign Minister.

- Inform national and international audiences about the objectives of upcoming high-level meetings with China – in the form of public statements or op-eds, as then-German Chancellor Olaf Scholz did ahead of a visit to China in 2022.

- Ensure timely and comprehensive readouts after meetings with Chinese officials to present national positions – ideally with reference to previously outlined objectives – and avoid Beijing’s version dominating public narratives about the exchange.

- Invest in China-related resources in government departments dealing with FIMI.

- Brief domestic experts and EU counterparts to share insights, communicate stances and coordinate responses.

- Stick to the language used in European Council statements on China – for example, the June 2023 conclusions covered issues of the highest strategic importance: China’s role in Russia’s war against Ukraine and stability in the Taiwan Strait.

The author would like to extend gratitude to Carla Zappen, a former intern at MERICS, who contributed to the research underpinning this analysis.

This analysis was made possible with support from the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.