Introduction

You are reading the Introduction of the report "Shaky China - Five scenarios for Xi Jinping's third term". Click here to go back to the table of contents.

In March 2023, Xi Jinping sealed a third term in power heading both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese state. His victory overturned more than 30 years of collective leadership and was enabled by constitutional amendments. Xi’s ambitious political agenda and handpicked leadership team will shape China’s path at a decisive juncture; the next five years could emerge as a tipping point in China’s rise or its stagnation. To manage this phase, Xi has established a system of party-state steering that restores centralized power and control and is continuing to centralize political and economic life still further. Tight control is Xi’s preferred way to grapple with China’s unprecedented socio-economic challenges. It is far from clear if this path will be successful, but if it is Xi may well seek to extend his third five-year term into a fourth one.

The one forecast that can be made with confidence is that in “Xi III”, China is entering a phase of increasing uncertainty. It is one of the few matters on China’s leadership and mainstream foreign China analysts agree. Whatever path China takes will have serious implications for its own people and the rest of the world.

This study lays out five scenarios for China’s path over the next five years in order to help formulate strategic responses. As with all scenario exercises, these are not predictions of the future. They are a framework for mapping and tracking key dynamics that will shape China’s trajectory and a tool for policy makers and businesses to stress test strategies and action plans against different pathways.

Three trends shaping China’s next five years: Slower growth, external pressure and increased centralization of power

No one doubts that Xi has fundamentally changed China in his first ten years in power, regardless of how they view him. Xi has already put in motion dynamics that will continue to deliver significant change in the years ahead. China is already very different from when Xi took over in 2012/2013. In the immediate post-Mao era, the CCP established a peaceful transition of power based on two-term limits and age limits. Under this system, power passed from Deng Xiaoping to Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao to Xi. He broke with party tradition when he clinched a third term as the party’s General Secretary at the 20th Party Congress in October 2022, though the move was universally expected as Xi signaled his intentions in 2018 by abolishing the two-term limit for the party post of PRC Chairman - a title usually held by the state president. In 2022, Xi installed a new leadership team of (overwhelmingly male) cadres of proven personal loyalty and effectiveness at implementing his political agenda. The annual meeting of China’s largely ceremonial parliament in March 2023 approved Xi’s third term as president, clearing the way for his ambitious “New Era” agenda. As the “New Era” includes a fundamental reorganization of government institutions to further tighten the party’s control over all state organs, it is likely that China’s governance will look very different by the 21st Party congress in 2027.

Three trends that shaped China in Xi’s first and second term (Xi I and Xi II) will also be particularly relevant for China’s development in Xi III: Slower growth, external pressure and increased centralization of power.

Slower growth

China’s economic growth, the engine of its tremendous progress since the 1980s, is facing a long-expected slowdown as the easy gains of catch-up development fade. Growth from infrastructure construction and low-tech exports has run its course. But China has not yet made the shift to a more sustainable growth path built on better paid jobs, increased technological capabilities and less environmental damage. The challenges of this economic transition were anticipated long before Xi came to power. During his first term (Xi I), the effects became fully visible, but were relatively well controlled, as growth rates descended from the double-digit-era of the early 2000s to around 6 percent annually. In Xi’s second term (Xi II), growth volatility started to pose serious tests for stability. Although triggered by the Covid-19 crisis, they stemmed from many underlying factors – low productivity and high dependence on exports or government investment. In Xi’s third term, China’s socioeconomic challenges will carry the risk of significant crises, even by the party’s own assessments, which cite negative demographic trends, financial stress and external pressure.

External pressure

The changing international environment is the second main trend seriously impacting China’s trajectory, in particular the rivalry between China and the United States. In 2013, Xi inherited a Sino-US relationship that, though stressed and competitive, was fairly stable. Relations deteriorated during Xi’s first term and longstanding conflicts moved to the forefront, beginning with tensions over US president Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and the on-and-off volatile hostility during President Donald Trump’s tenure. Under the Biden presidency, the relationship has moved towards the more systemic competition and sustained confrontation. As Xi’s third term gets underway, both the United States and China are locking in their security, economic and technology policies with the determination to prevail in a long, fierce rivalry to be the world’s leading power.

The combination of slowing growth and a shifting, more volatile international environment is producing considerable socioeconomic stress.

Centralization of power

Xi has centralized power in a way not seen since – and in some ways exceeding – the era of Mao Zedong. The party frames its push towards centralization and control as a necessary and effective policy response to rising socioeconomic challenges. Strengthening the CCP with himself at the core, has also been a priority of Xi’s and one that he has fulfilled successfully. In effect, he put in place a system in which he wields so much authority that even China’s policy mistakes during the Covid 19 crisis were no serious challenge to his position, despite sparking rare public demonstrations of anger.

Although Xi and the CCP leadership have achieved their top priorities, even they concede that China has moved from a stressed, but rather stable country to one that is more unstable and less predictable in the ten years since 2013. The fact that “stability and control” are now key concepts of Xi’s agenda underscores what shaky ground the system is standing on. In an unstable environment, pathways can easily lead into other, more extreme scenarios.

Five scenarios for a shaky China

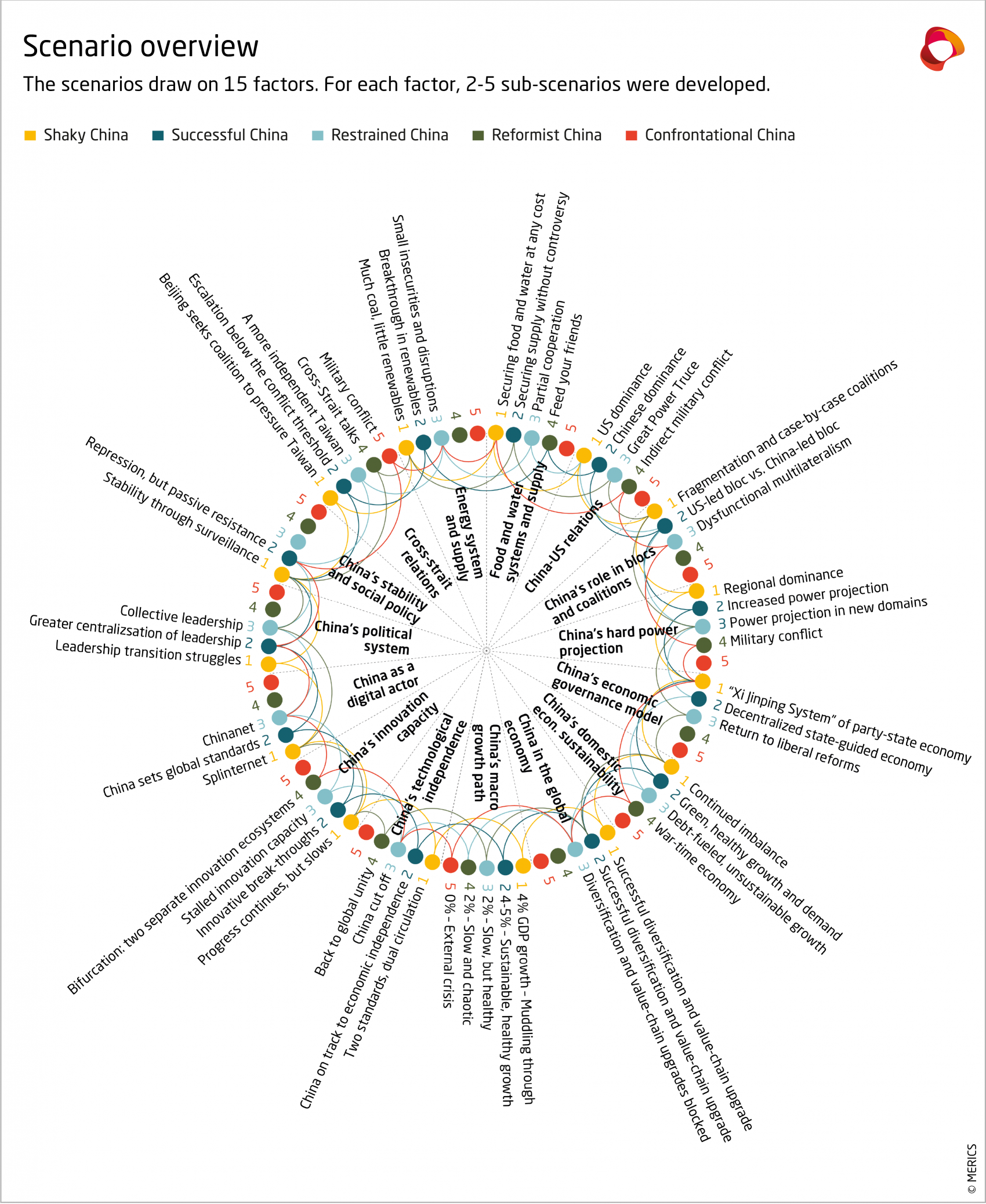

Whether this less stable and less predictable China becomes the “new normal”, or whether China experiences more radical shifts, will depend on developments in different arenas. This study therefore draws on 15 factors which are key for China’s future path. These include

Political and social factors

- China-US relations

- China’s role in blocs and coalitions

- China’s hard power projection

- China's political system

- China's stability and social policy

- Cross-strait relations

- Energy system and supply

- Food and water systems and supply

Economic and technological factors

- China’s economic governance model

- China’s domestic economic sustainability

- China in the global economy

- China’s macro growth path

- China’s technological independence

- China's innovation capacity

- China as a digital actor

For each factor, sub-scenarios were developed and tested for mutual influence and consistency (see methodology chapter). Since many factors influence one another, major developments in some areas could generate changes in other dimensions and potentially shift China’s trajectory into a totally different scenario.

Looking at potential developments within the different factors has led us to formulate five distinct scenarios.

The baseline scenario is a “Shaky China”, in which China’s economy, politics and engagement with the world follow the trends seen at the outset of Xi’s third term in office. It is a ‘muddling through’ scenario in which China neither makes impressive progress nor faces existential crisis.

“Shaky China” is an unstable ‘status quo’ scenario. However, significant changes in some of the underlying factors could create pathways to cross over into one of four more extreme scenarios:

- Confrontational China: In this scenario, tensions over Taiwan escalate to a point where the grey-zone conflict is heightened enough to make open military conflict feel increasingly likely. This generates extreme bifurcation and significant decoupling between China and the West.

- Successful China: In this scenario, China is perceived to achieve key goals in Xi’s agenda: all-encompassing party-state control, a shift to sustainable green growth, technological independence, and regime security and global influence rivalling the United States. China’s success is aided by the West’s huge homegrown problems.

- Restrained China: Here, China’s internal weaknesses, plus coalition-building by the United States and likeminded countries, hamper Beijing’s efforts to diversify the economy, maintain growth, achieve technological independence, build external coalitions or pursue an effective global power play.

- Reformist China: In this scenario, China's internal crises result in a political course correction. The confrontation between China and the West is reduced amid expectations of a return to "reform and opening up", if under new circumstances.

Likelihood of scenarios

All scenarios are possible. More extreme scenarios, which are theoretically possible (e.g. democratic reforms, a revolution, a collapse of the system) were considered during the process, but not included.

Possibility does not mean that a scenario will be realized in full. Trajectories and perceptions of them also matter. For instance, even if China does not become a global leader in future technologies, a breakthrough in a single technology could lead to a perception that China is on track to achieving this goal. A general reassessment of investment patterns might follow. Likewise, a continued perception of escalation also creates facts in the form of military spending or new alliances.

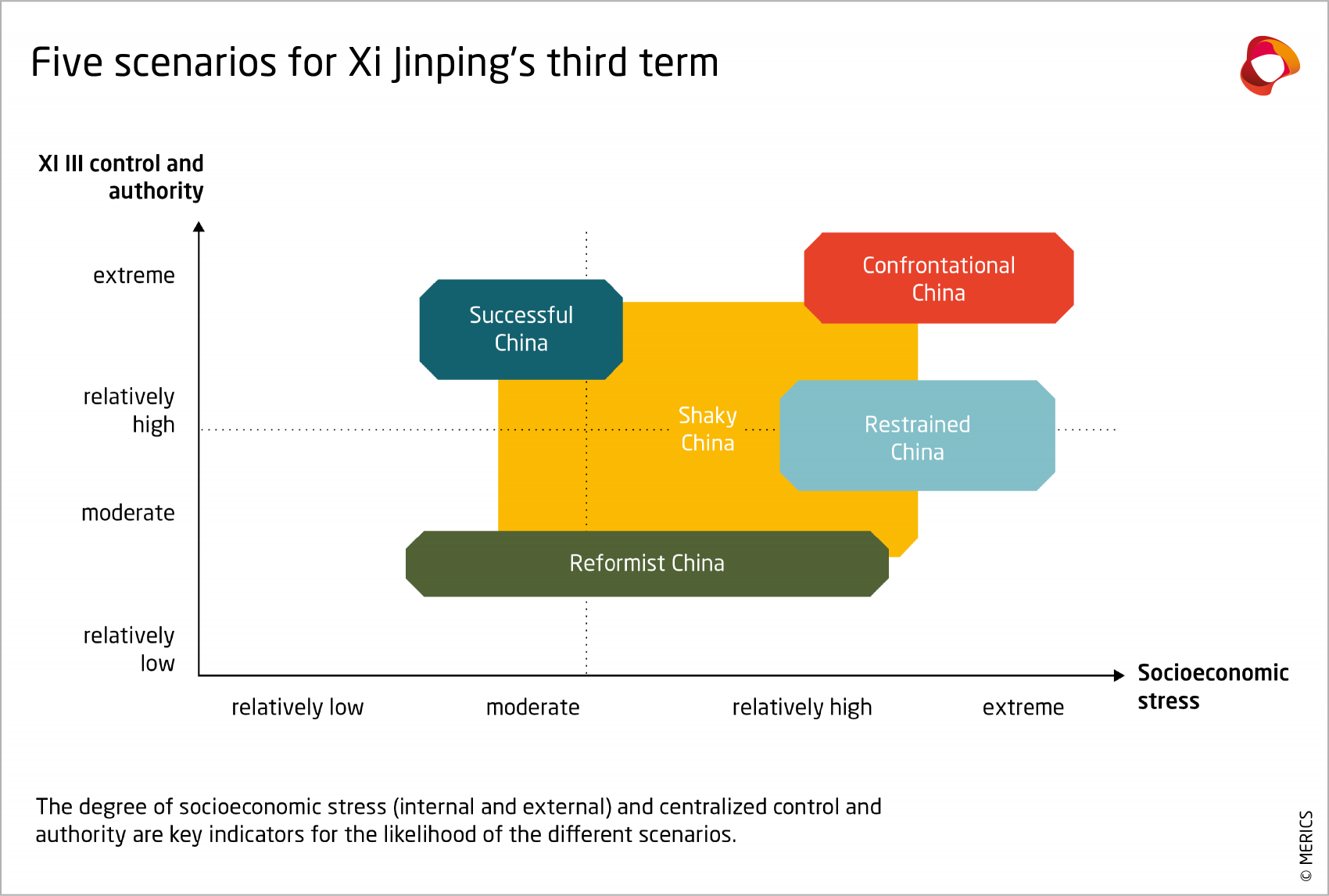

Exhibit 1 takes the degree of socioeconomic stress (internal and external) and centralized control and authority as the key indicators of the likelihood of different scenarios. The top right quadrant indicates current levels. “Shaky China” covers the broadest range of different levels of stress and centralization. Should socioeconomic stress rise even further, both a “Confrontational China” or a “Restrained China” become more likely, depending on external developments. A “Successful China” becomes more realistic if the CCP were to prove extremely successful at mitigating socioeconomic stress and achieving industrial policy breakthroughs (especially if boosted by an external crisis facing the West). A “Reformist China” would imply significant decentralization of power and currently seems almost impossible.

Dealing with a shaky China

Xi has done away with many of our assumptions about China during the last ten years. Many strategies that governments and businesses developed in the 1990s and early 2000s were built on the conviction that China would continue to open up – perhaps not in a linear fashion, but along an overall trajectory of greater integration with the world economy and global political frameworks. At the beginning of Xi’s third term, it is clear that this was wishful thinking. Many now see China not as the market of the future but as the cluster risk of the future.

European policy makers and private businesses alike need to understand the realities of a more “Shaky China” and the possibility of a shift into more extreme scenarios. The risk exposure of individual actors and opportunities associated with different scenarios, vary greatly. Whatever their situation, three steps are needed: an analysis of risks and opportunities; a reassessment of preparedness and mitigation measures; and tracking the potential triggers that could bring a change in China’s trajectory.

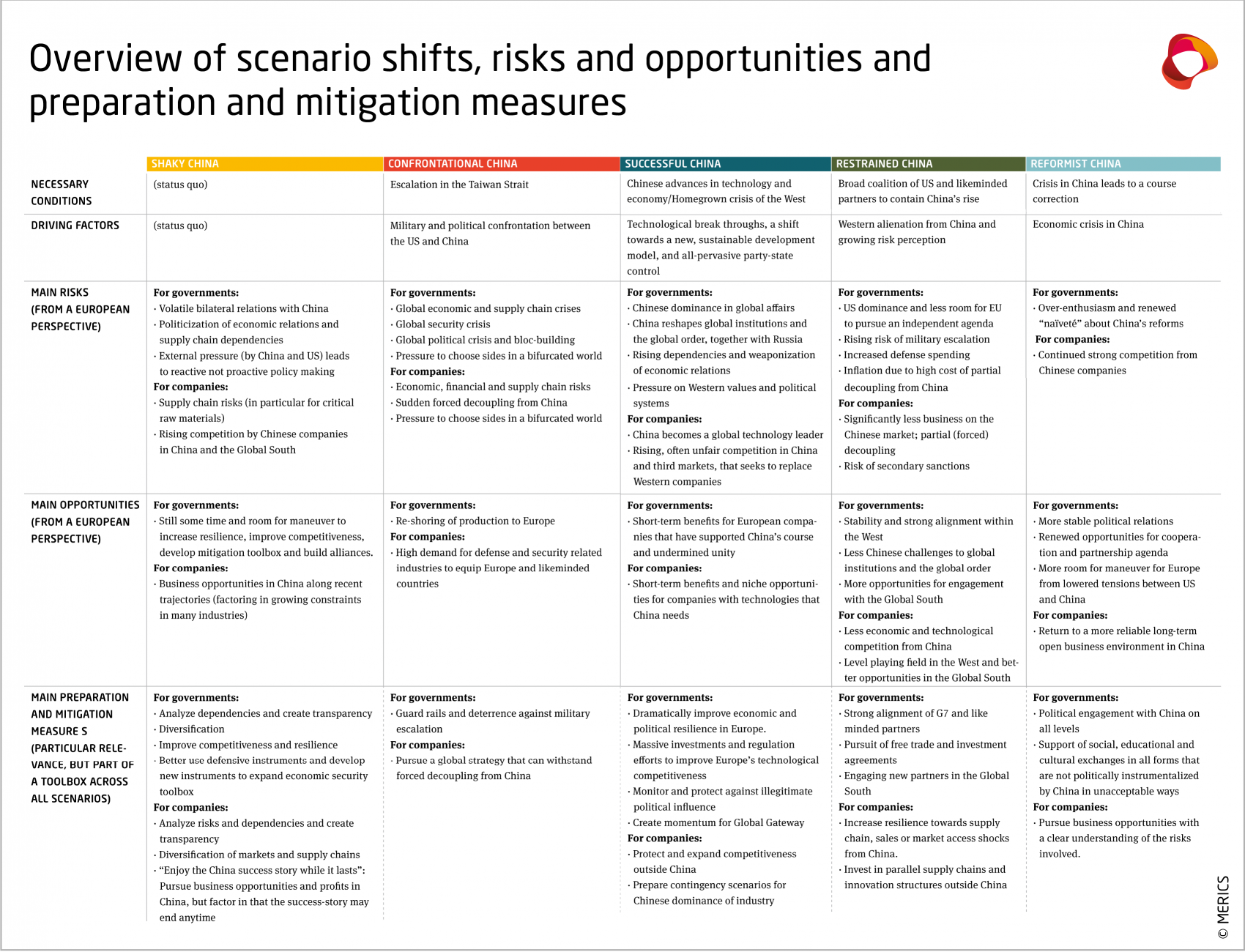

Analyzing opportunities and risks

In Europe, policy makers and private businesses alike need to find a new balance between China-related risks and opportunities. Every scenario comes with its own specific opportunities and risks. Also, every individual actor – a national or a subnational government, a business or a university - has different risk exposure, or may perceive specific opportunities. Understanding these risks and opportunities and their strategic implications needs an individual analysis. What we provide here is a broad overview from the perspective of European policy makers and corporates.

Shaky China: As this is the “dynamic status quo” scenario, European governments face risks from volatile bilateral relations with China. Concerns include the politicization of economic relationships and supply chain dependencies. With the United States and China exerting substantial pressure, European states risk pursuing reactive policies rather than proactive policy making. This could lead them to overlook the opportunity that the “Shaky China” scenario presents; namely that there is still time, and room, for maneuvers to increase resilience, improve competitiveness, expand the mitigation toolbox and build alliances. European companies can pursue their China business strategies along recent trajectories (with signals about an increasingly constrained business environment already factored in). But they need to be aware of risks arising from more intense competition from Chinese companies, both in China’s market and third countries.

Confrontational China: This scenario entails the most detrimental disruption of the status quo. European governments and global institutions would face the need to react to global economic and supply chain crises; a global security crisis; and a global political crisis – all at the same time. Countries around the world would be under intense pressure to “choose sides” between the United States and China. For Europe, this would mean an obvious, though not pain-free, choice in favor of the transatlantic partnership. A very thin silver lining might lie in the opportunity to reshore some business operations to Europe. European companies would be confronted with the massive effects of a global economic and financial crisis. Sanctions and political pressure could force corporates into sudden decoupling from China, similar to their exit from the Russian market in 2022. The very few beneficiaries would be defense and security-related industries because defense expenditures would rise in European, and likeminded, countries.

Successful China: This scenario, in which China is perceived to be relatively more stable, resilient and future-oriented than the West, comes with the risk of a gradual erosion of the existing world order. European governments would be confronted with an increasingly assertive China that – together with Russia – moves to reshape global institutions according to its own interests. Economic dependencies on China would rise and would be increasingly weaponized. Also, China would exert increasing pressure on Western values and political systems. European governments that previously supported China’s course (at the cost of European and Western unity), stand to gain short-term benefits from privileged ties with Beijing, but would also lose their longer-term room to maneuver. European companies would need to operate in a world market where, increasingly, China is the technology leader that sets standards, dominates supply chains and aims to replace Western companies with Chinese ones. Businesses would face rising, often unfair competition in China and third markets, except for some short-term benefits and niche opportunities in industries where China urgently needs foreign technology.

Restrained China: This scenario is implicitly or even explicitly pursued by mainstream US China policy; it could create high political and economic costs on the European side of the Atlantic. European governments might find it harder to pursue an independent agenda vis-à-vis an emboldened United States. The risk of military escalation in the Pacific region may require increased defense spending. Partial decoupling from China would bring high costs and rising inflation. Nevertheless, a “Restrained China” scenario would also come with significant political opportunities: stability due to a strong alignment between likeminded countries; diminishing Chinese challenges to the global order and institutions; and more room for engagement with the Global South. European companies would suffer from their China business shrinking; partial (forced) decoupling; and the risk of secondary sanctions. The benefits include less economic and technological competition from China, a more level playing field in the West and better opportunities in the Global South.

Reformist China: Here, confrontation between China and the West would ease. European governments and companies would have far more opportunities than risks. These include more stable political relations with China; renewed opportunities for pursuing cooperation and a partnership agenda. Lower tensions between China and the United States could yield greater political leeway for Europe. The risks would lie in over-enthusiasm and renewed naïveté towards China’s reforms and ambitions. A more pragmatic “Reformist China” is not necessarily a weaker or more Western oriented China. European companies would still experience strong competition from Chinese companies, but could compete in a more reliable, open business environment, which is more encouraging for long-term engagement.

Planning preparation and mitigation measures

To prepare for the risks we have outlined, policy makers and private enterprises alike need a full-fledged portfolio of mitigation measures. In the EU, measures are currently being discussed and developed around the concept of “de-risking”, endorsed and mainstreamed by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in her March 2023 speech on China.

To build robust strategies for a “Shaky China” that could move into various more extreme scenarios, actors need to consider various pathways rather than preparing for a single scenario. Preparation and mitigation measures should therefore be discussed and implemented as a package, even if some are more relevant to some scenarios than others.

Preparation and mitigation measures for European governments include

- Analyzing and creating transparency about supply chain dependencies (in particular, for critical raw materials)

- Taking measures to bolster supply chain resilience (e.g. through diversification, reshoring)

- Pursuing measures to radically improve Europe’s economic and technological competitiveness

- Providing political support for diversification of markets for European businesses

- Making better use of existing defensive instruments in the European economic security toolbox (e.g. investment screening, economic coercion instrument)

- Developing new instruments to expand Europe’s economic security toolbox (e.g. through outbound investment screening)

- Creating momentum for Global Gateway and other initiatives to engage more with the Global South

- Pursuing free trade and investment agreements with likeminded partners and the Global South

- Aligning better with the G7 and other likeminded partners

- Pursuing a proactive Asia Pacific strategy, including developing and supporting guard rails and deterrence measures against military escalation in the region

- Monitoring and protecting against illegitimate Chinese political influence operations

- Engaging with China politically on all levels

- Supporting social, educational and cultural exchanges in all forms that are not politically instrumentalized by China in unacceptable ways

Preparation and mitigation measures for European companies

- Analyzing risks and dependencies and creating transparency about them

- Pursuing a global business strategy that can “survive” forced decoupling from China

- Protecting and expanding competitiveness outside China

- Diversifying markets and supply chains (e.g. by investing in parallel supply chain and innovation structures outside China)

- “Enjoying the China success story while it lasts”: Pursuing business opportunities and profits in China, with a clear understanding of the risks involved and factoring in that the success story can end anytime

- Preparing contingency scenarios for Chinese dominance of industry

Tracking triggers

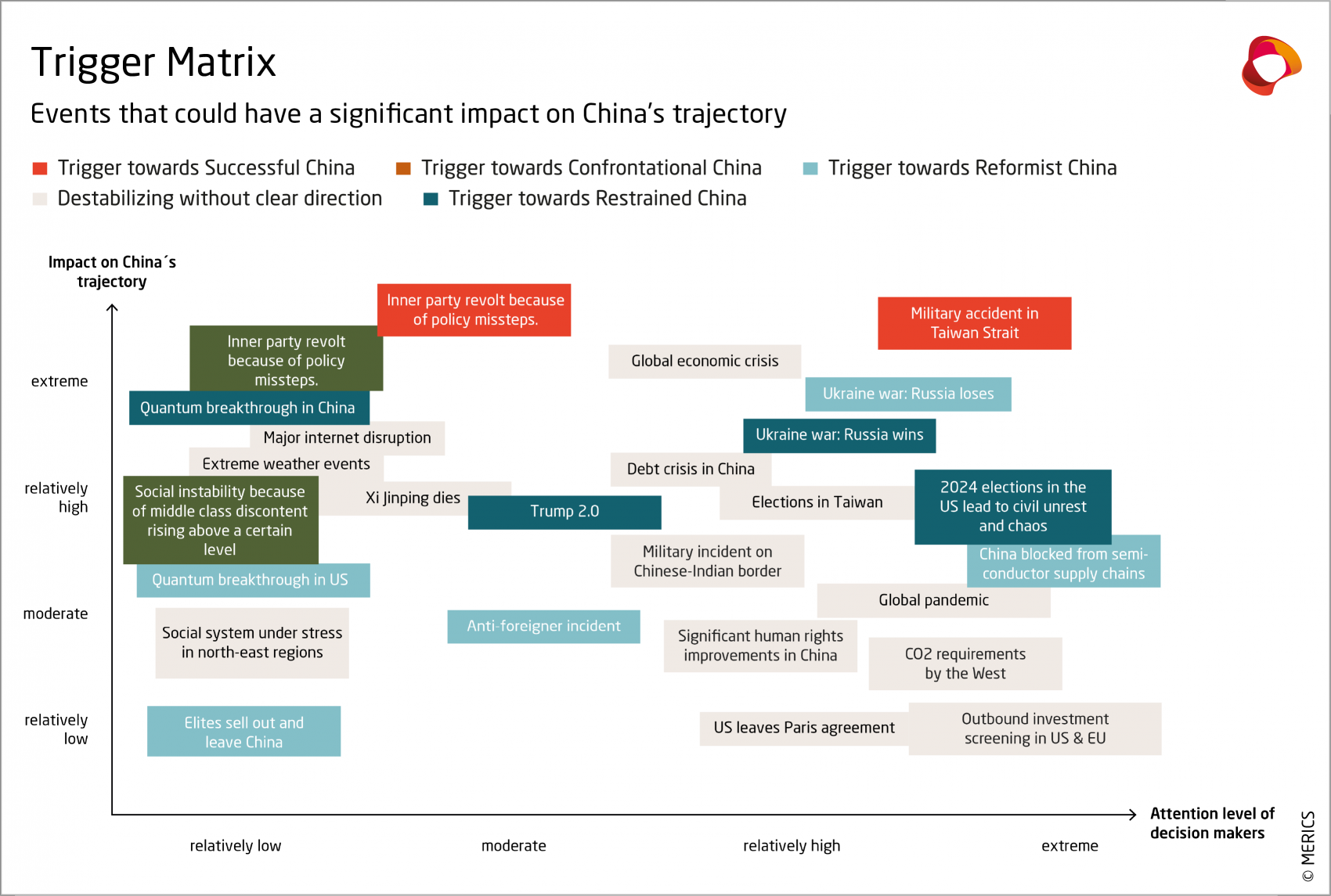

The third step in dealing with a “Shaky China” – besides analyzing risks and opportunities and implementing mitigation and preparation measures - lies in tracking change and potential shifts from the baseline scenario to other, more extreme scenarios. Many developments happen gradually, and major movements only become visible in hindsight. Nevertheless, a China that is under considerable socioeconomic stress and where major decisions are increasingly centralized, might be more likely to experience sudden developments. At the same time, internal or external shocks could push China further into new directions. The same can be said for major Chinese successes.

Policy makers and businesses should develop forecasting and monitoring exercises to identify triggers that could have significant impact. Again, relevant triggers vary for different actors. The following chart gives an overview of triggers that could turn out to be significant and deserve the attention of decision makers:

You were reading the Introduction of the report "Shaky China - Five scenarios for Xi Jinping's third term". Click here to go back to the table of contents.