CAI + Sanctions + EU Digital Compass

Story of the month: CAI – looking beyond market openings

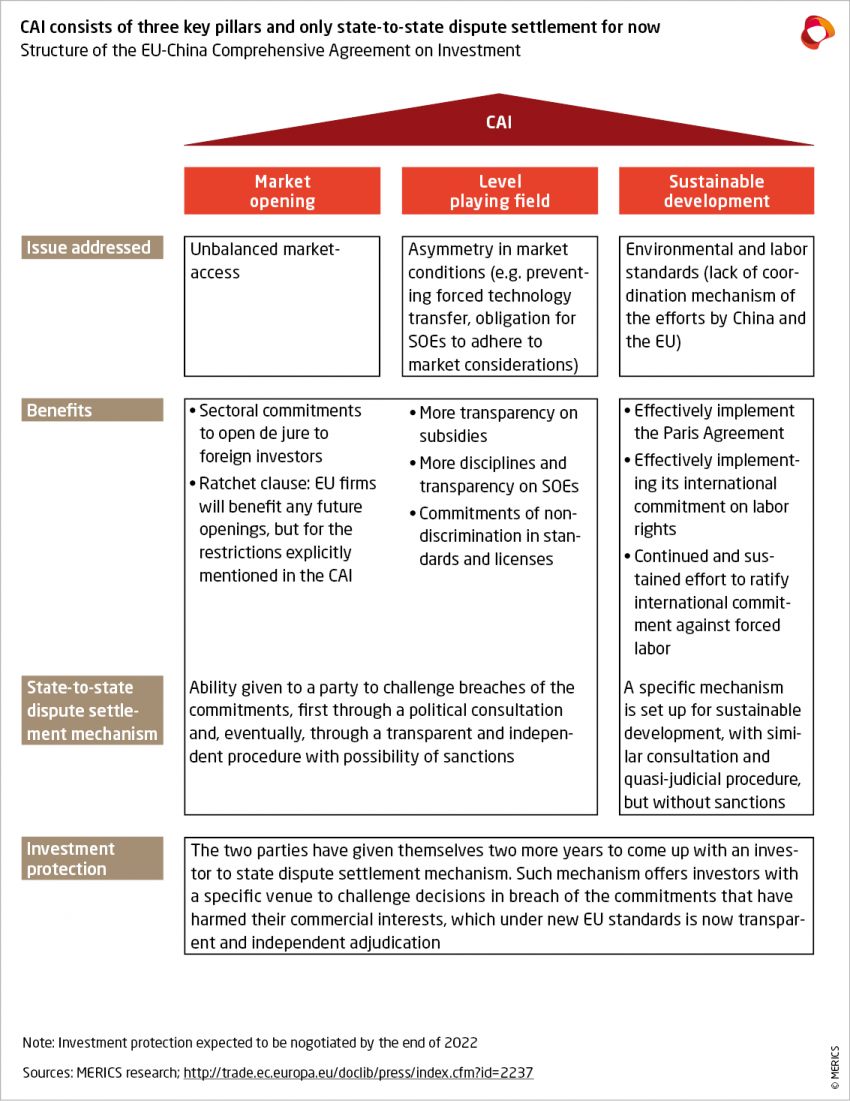

The Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), agreed in the final hours of 2020, is now fully out of the woods since the details of market opening were published in mid-March. However, the complexity of this document both reflects the murky business environment foreign firms navigate in China, and the limits of what is on offer in terms of market opening. In a long-term perspective, the agreement’s real advances may lie in the enforcement and the level-playing-field pillars if they are properly implemented.

Meaningful openings limited to new energy vehicles (NEV), renewable energies and some services

With the details of the market-opening pillar now out, it is possible to see a few improvements the agreement would bring to the current trend in China for targeted opening up. First, the CAI’s ratchet clause means that any further opening up China offers will be automatically extended to EU firms. And for new energy vehicles (NEV), investments are only restricted by the utilization rate of the sector in the province and the completion of previous projects, although both restrictions are removed for investments over USD 1 billion. The value of that last commitment seems limited, considering that Tesla and its giant factory in Shanghai received similar treatment back in 2019.

In wind and solar renewables, on the top of a non-discriminatory commitment, the EU has obtained a new strong form of reciprocity that gives the possibility of capping Chinese firms’ involvement in each EU member state at the level of the market share of EU firms in China. In services, hospitals (which were already opened in 2014, on paper at least) and clinics are now open for foreign investors in eight of the largest Chinese cities, plus Hainan province. Besides, the “technological neutrality” commitment enables companies to provide services online that they offer unconstrained offline.

Contrary to expectations, cloud services remain restricted to a 50 percent equity cap. China has also committed to remove joint-venture obligations in various business services activities, such as leasing services, management consulting and various environmental services (sanitation and solid waste disposal, among others). All the opening up in services applies to all firms wherever they are based, but only EU firms benefit from the fairly independent and transparent dispute mechanisms provided by the agreement to enforce the new provisions.

Additional value beyond opening up market access – enforcement and level-playing-field commitments

The agreement’s main value-added on market access is not so much in opening up but in providing an enforcement mechanism for most of the opening up China carried out over the past few years. This offers a opportunity for tackling the multiple, murky ways in which China hinders opening up even as it formally carries it out. The substantial provisions for a level playing field, including participation in Chinese standard-setting bodies and non-discrimination in purchases from SOEs, could also be considered as breakthroughs for EU firms to expand on the Chinese market.

All these technical points could be swept away by mounting geopolitical tensions

The current deterioration of Sino-European relations weighs significantly on the likelihood of the CAI being ratified. The Federation of German Industries acknowledged last week that “China's unyieldingly hardline stance in Hong Kong and Xinjiang clouds prospects for ratification of the CAI.”. On top of that, the ambitious schedule put forward by the Commission aims at ratification in the first six months of 2022, under a French presidency of the Council. France will then be in the run-up to a presidential election in which President Macron will likely be eager not to be depicted as pro-globalization, pro-business and unconcerned about human rights.

Read more:

- European Commission: Slide presentation of the CAI by the Commission

- European Commission: Commission publishes market access offers of the EU-China investment agreement

- European Parliament (EPRS): EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment Levelling the playing field with China

- Peterson Institute for International Economics: The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment: will it be a game changer?

- SME Europe: Impacts of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment

- SCMP: EU-China investment deal faces backlash in European Parliament

- Politico: China throws EU trade deal to the wolf warriors

Sanctions dispute between the EU and China – What comes next?

Quote: “The retaliation taken by China against the decision of sanctioning some officials for [human rights violations in] Xinjiang has created a new atmosphere." - Josep Borrell, High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the European Union

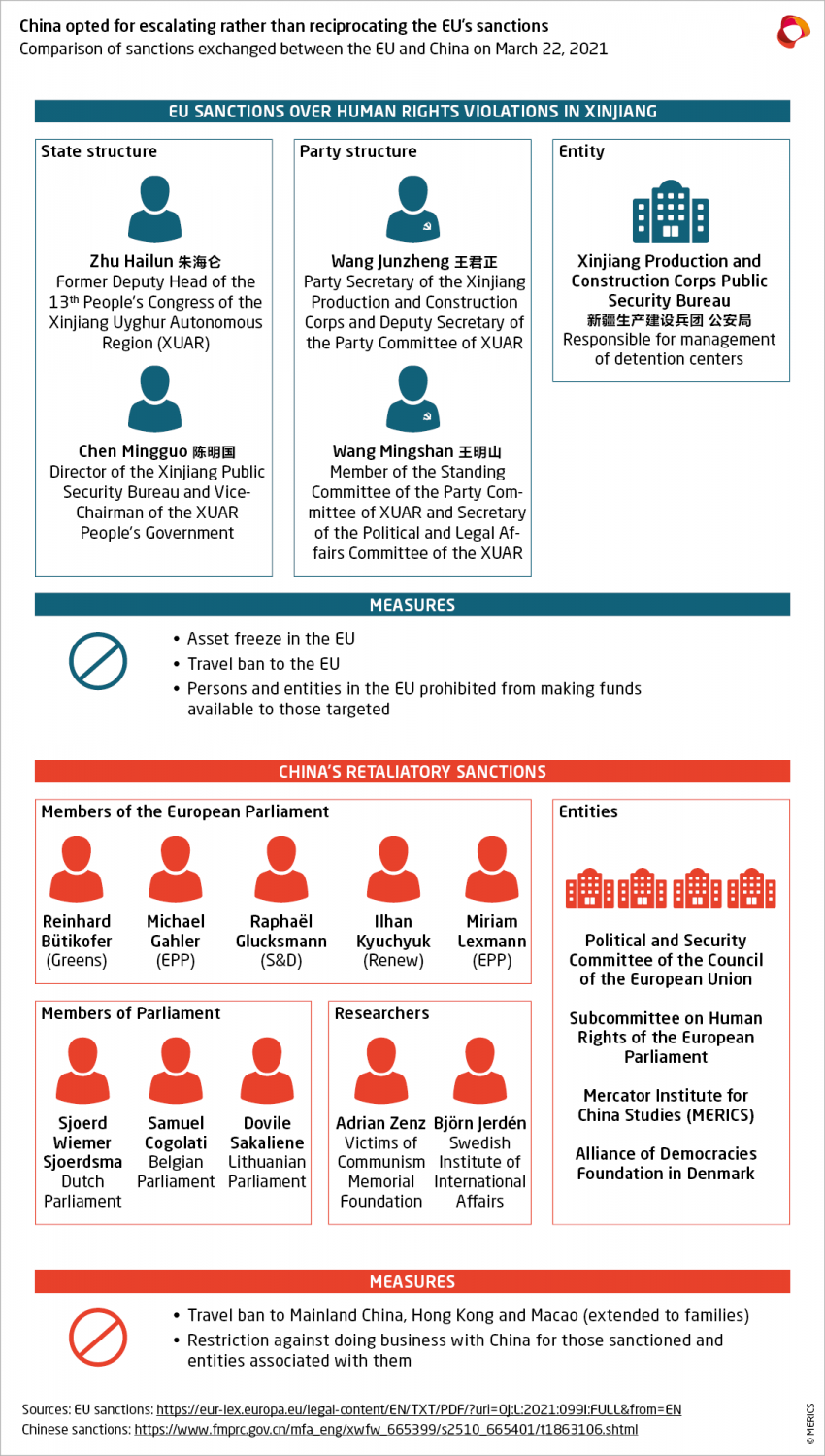

The EU’s human rights sanctions and China’s retaliation on March 22 (detailed account available here) created what the High Representative, Josep Borrell, called a “new situation” in EU-China relations. The move is indeed historic – it is the first time that the EU has imposed sanctions on China since 1989 and the first time that China has openly sanctioned European lawmakers, think tanks and researchers.

In the aftermath, most political groups in the European Parliament called for the suspension of discussions on the ratification of the CAI as long as Chinese retaliatory sanctions remain in place. The exception is the European People’s Party which would prefer to continue work on the CAI and to separate political and economic tracks.

In China, European companies that have in the past voiced concerns over the alleged forced labor practices in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China became a target of boycott campaigns. For instance, the Swedish clothing company H&M had its products removed from major e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba’s Tmall, JD.com or Pinduoduo after its one-year-old – and now deleted – statement. The statement claimed that it doesn’t use cotton produced in Xinjiang and resurfaced online in posts by influential groups such as the Communist Youth League.

MERICS take: The sanctions imposed by the Chinese side are ambiguous in terms of their practical impact. The lack of clarity is intentional – the aim is to create uncertainty so that researchers and politicians shy away from touching issues considered to be sensitive and increasingly self-censor.

The EU is not interested in escalating the tensions further, but the two sides also have no easy way to de-escalate. In fact, similar disputes are likely to become a feature of EU-China relations going forward and political clashes are likely to spill over to other aspects of the relationship. The cases of H&M and other clothing companies targeted over their Xinjiang-related statements show that Beijing is willing and able to deploy economic leverage over European companies in retaliation to political criticism.

What to watch: Stakeholder consultations on an EU “anti-coercion instrument” have just started. The instrument is expected to be unveiled by the end of this year and could address economic interference in EU policy choices. Already before that, political tensions might increase when the EU moves forward with the supply chain due diligence system – expected to be proposed by the Commission in June – and once European companies investigate labor conditions in their Chinese supply chains in greater detail. Lingering debates over a potential boycott of the upcoming Beijing 2022 Olympics could further complicate the diplomatic picture.

Read more:

- Reuters: EU, China impose tit-for-tat sanctions over Xinjiang abuses

- FT: Sanctions row threatens EU-China investment deal

- EEAS: Press conference of the High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell following the Foreign Affairs Council on March 22

- MFA of the People’s Republic of China: Regular Press Conference on March 23, 2021

- SCMP: As Xinjiang cotton row rages, European firms ‘caught between rock and hard place’

- New York Times: What Is Going On With China, Cotton and All of These Clothing Brands?

- European Commission: Strengthening the EU’s autonomy – Commission seeks input on a new anti-coercion instrument

Radosław Sikorski on EU’s sanctions row with China and the transatlantic partnership

In the latest MERICS podcast, Radosław Sikorsk, MEP (EPP) and Chair of the European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with the United States, discusses what the sanctions mean for the EU’s China policy, prospects of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy and what are the future of transatlantic relations. He argues that the EU will “collaborate with the US [...] on practically everything except the military field.”

Transatlantic partners make progress in finding a common language on China

Quote: "Authoritarian tendencies morphed into new models. […] More than ever, it is up to America and Europe, with our like-minded partners, to promote the democratic model and free market economy." Charles Michel, President of the European Council

The EU and the US have been struggling to find a common language on challenges posed by China. Throughout March the two sides made gestures of goodwill towards each other, for example, working to resolve the dispute between Airbus and Boeing, and intensified their discussions on the future of the transatlantic relationship – including in the context of China. Berlin and Paris were briefed by the Biden administration ahead of the US-China Alaska summit and top European officials exchanged their views with Secretary of State Antony Blinken during in-person meetings in Brussels between March 23 and 24.

Here are the key meetings and how China featured in them:

- March 23-24: In-person summit of NATO foreign ministers, during which the ministers discussed the challenge that China’s activity poses to multilateral rules-based order supported by the alliance.

- March 24: Relaunch of the transatlantic dialogue on China that was established last year. The framework is to feature dialogue at “senior official and expert levels” covering multiple issues ranging from economic affairs or human rights to engagement with China on climate change.

- March 25: European Council video summit included a discussion between EU27 and the President of the United States – the first meeting in such format in 11 years. During the meeting, the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, made remarks on how new authoritarian models pose a challenge to democratic free market economies.

MERICS take: The transatlantic partners made progress in establishing a common understanding of challenges associated with China. During his trip to Brussels, Blinken made it clear that the Biden administration recognizes the multifaceted nature of relations with China and “won’t force allies into an ‘us-or-them’ choice with China” – a choice the EU rejects to make. At the same time Brussels echoed, more strongly than in the past, Washington’s narrative of competition between democracies and authoritarian systems.

As to the substance, the issues high on the agenda that link to China include:

- Developing a digital economy rulebook and digital democratic standards

- Reforming the global trading framework including the WTO

- Boosting cybersecurity and anti-disinformation cooperation within NATO structures

- Upholding democratic values and the rules-based multilateral order

These points amount to ensuring that market liberal democracies continue to thrive in a more competitive global environment increasingly shaped by China.

What to watch: Brussels sent signals of support for transatlantic cooperation on China, but the extent to which these signals will be translated into actual foreign policy efforts depends chiefly on European capitals. The process may not be smooth with Germany being conscious of the economic importance of China and France eager to underscore independent European agency. There is also the matter of how the Biden team’s commitment is divided between transatlantic and transpacific partnerships.

Read more:

- Politico: China’s hardline turn lifts chances of deeper EU-US alliance

- Reuters: U.S. won't force NATO allies into 'us or them' choice on China

- European Council: Introductory remarks by President Charles Michel at the videoconference of EU leaders with US President Biden

- EEAS: Joint press release on the meeting between High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell and the U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken

- MERICS: Towards 'extreme competition': Mapping the contours of US-China relations under the Biden administration

- Atlantic Council: The China Plan: A Transatlantic Blueprint for Strategic Competition

EU’s Digital Compass raises prospects of a European alternative to China’s Digital Silk Road

Quote: “In a world marked by geopolitical competition for technological primacy, we must ensure that the EU’s vision of digitalization – based on open societies, the rule of law, and fundamental freedoms – proves its worth over that of authoritarian systems that use digital technologies as tools for surveillance and repression.” Margrethe Vestager, European Commission Executive VP and Commissioner for Competition, Josep Borrell, High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the European Union

On March 9, the European Commission presented the Digital Compass – its vision for translating into action the EU’s ambitions for digital transformation by 2030. The Digital Compass mainly outlines the bloc’s targets in the four areas of digital skills, infrastructure (5G, cutting edge-semiconductors, data and computing), and the digitalization of business and public services. However, the communication is inherently geopolitical in its outlook. In a section devoted to international cooperation, it stresses the linkage between digitalization and global influence and places strong emphasis on international partnerships, acknowledging that “digital policy is never value-neutral.” China is not named, but the emphasis on democratic and rights-based alternatives to Beijing’s vision for digital transformation is apparent.

Some noteworthy points:

- Promotion of EU norms and standards on issues ranging from data protection, privacy and ethical AI to cybersecurity, e-government and tackling disinformation online.

- A Digital Connectivity Fund to support developing and emerging economies bridge the digital divide.

- Joint research on issues such as 6G, quantum technologies and digital technology solutions to climate change.

- Progress towards a coalition of like-minded partners that share values and cooperate on issues such as innovation, standard setting in multilateral fora, digital trade and a secure cyberspace.

MERICS take: Digital connectivity is going to be increasingly central in the technological competition with China. Through its Digital Silk Road, China aims to be at the center of global networks to shape not just markets, but also digital infrastructure and the digital future of developing and emerging economies across the globe. Backed by policy and financial support, Chinese ICT firms have long established themselves as leading providers of telecommunications infrastructure, from network equipment and subsea cable systems to smart city platforms – including surveillance applications.

While the EU does integrate digital and development cooperation policies, it has often lacked ambition when it comes to delivering connectivity to underserved countries and regions. If the EU and its member states want to provide safe, sustainable and secure alternatives to China’s offerings, devoting more resources to external connectivity will be key.

What to watch: 2021 will be a litmus test for the bloc’s digital connectivity agenda, as the Commission is set to release a Global Digital Cooperation Strategy. The year started off well, with the completion of the EllaLink submarine cable system linking Europe and Latin America. This was followed by a ministerial declaration in which 25 member states, plus Island and Norway, called on the EU to map and strengthen connectivity in and with other parts of the world and committed to taking relevant initiatives, such as identifying international projects to be pursued through the new Digital4Development (D4D) Hub. Whether EU public and private actors can deliver targeted digital development projects based on real needs in partner countries remains to be seen. China has already proven its ability to do just that.

Read more:

- European Commission: Europe’s Digital Decade: Digital targets for 2030

- European Commission: Digital Day 2021: Europe to reinforce internet connectivity with global partners

- Project Syndicate: Why Europe’s Digital Decade Matters

- Center for Strategic and International Studies: Competing with China’s Digital Silk Road

- MERICS: The Digital Silk Road is a development issue

- Clingendael: Unpacking China’s Digital Silk Road

- German Marshall Fund (event recording): China's Digital Silk Road and Undersea Cables: Prospects and Threats Posed to the EU

The EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy may become a channel for competition with China

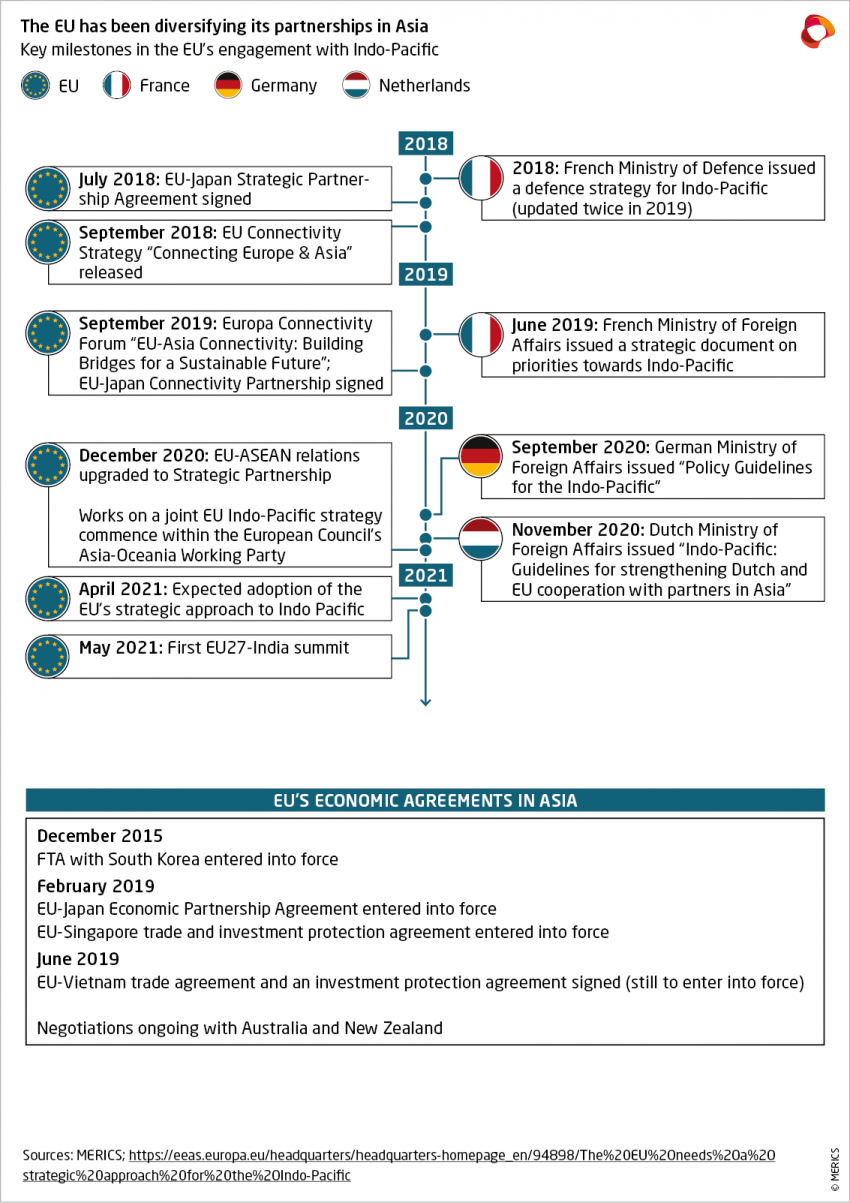

The EU is developing a joint Indo-Pacific strategy to strengthen and diversify its partnerships in Asia and to support regional efforts at expanding its openness and accessibility for trade. The stakes are high, as the Indo-Pacific is home to four out of ten of the EU’s largest trading partners.

A joint strategy was first discussed in December last year based on national Indo-Pacific papers put forward by France, Germany and the Netherlands. This month the matter picked up pace following a meeting on March 11 of the Asia-Oceania Working Group of the European Council, after which top European External Action Service diplomats signaled the expected content of the strategy.

The EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy is likely to:

- promote rules-based multilateralism pursued through cooperation with like-minded countries;

- focus on sustainable development and serve as an instrument for deployment of the EU’s connectivity policies including digital governance and climate change;

- support supply-chain diversification and efforts to ensure security of maritime routes under UNCLOS.

MERICS take: The EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy will have to navigate possible areas of competition and tensions with China. European efforts to deepen economic relations with the wider region and to cooperate with like-minded partners on the promotion of a sustainable and high-standards approach to trade and connectivity do not necessarily align with the interests of Beijing.

The EU’s move towards the Indo-Pacific and support for open maritime routes will also possibly raise tensions with China on a geopolitical basis. Freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea – like the ones currently being carried out by France and those planned by Germany – are likely to become more frequent. So far Beijing has not been particularly vocal about these, but this might change should member states decide to expand its relations with Taiwan or boost cooperation with the United States in the region. Engagement with the Indo-Pacific was among the topics discussed between transatlantic partners during the visits described in this briefing.

What to watch: More details on the EU’s plans for engagement with the Indo-Pacific are on the horizon. The related strategic approach is expected to be adopted during the next meeting of the Foreign Affairs Council on April 19. This will be followed by the first ever EU27-India summit on May 8. However, keep an eye out for whether real resources and concrete objectives are put on the table. The limited results of the EU’s Connectivity Strategy targeting Asia suggest that a dose of caution may be in order.

Read more:

- EEAS: The EU needs a strategic approach for the Indo-Pacific

- MERICS: MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker

- Elcano: Europe and the Indo-Pacific: comparing France, Germany and the Netherlands

- CSIS (video): Transatlantic Relations and the Indo-Pacific: Implications for Japan and Korea

- GMF: Agenda 2021: U.S.-Europe-India Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific