Crackdown on tech firms + CCP centenary + Hong Kong National Security Law

Top Story: Chinese crackdown sends shudders through tech sector

Chinese authorities on July 2 announced a cybersecurity investigation into Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing. A few days later, they announced a crackdown on “illegal securities activities,” including expedited revision of regulations concerning information security and confidentiality in relation to security issuances and stock market listings outside China. These moves followed Didi’s listing on the New York Stock Exchange, the biggest Chinese tech IPO in the US since Alibaba’s USD 25 billion listing in 2014.

This was the first announcement by Chinese authorities of a cybersecurity investigation into a large Chinese internet platform. On Monday July 5, it was followed by announcement of cybersecurity investigations into three other Chinese internet businesses, Yunmanman and Huochebang in the freight transport sector and Boss Zhipin in job recruitment. While investigations continue, all four companies are prohibited from registering additional users, and Chinese app stores are not allowed to offer Didi’s app.

The official announcements in each case cited “national data security risks,” “national security” and “public interests” as a reason for the measures. The services provided by the companies suggest that authorities were concerned about their management of the personal information of large numbers of Chinese citizens, including state employees.

The measures followed regulatory action in late 2020 against Alibaba’s Ant Financial and come in the context of continuing expansion of China’s data-regulation regime. Chinese authorities want to make the nation’s digital networks more secure and improve conditions for personal information protection and data markets. Chinese state media commented that companies like Didi cannot be allowed to accumulate and freely use “super databases” of personal information larger than those of the Chinese state.

These regulatory actions reflect concern by Chinese authorities over potential transfer of sensitive data held by Chinese internet firms to US authorities due to disclosure requirements for listing on US stock exchanges. Reporting indicates that Chinese authorities had warned Didi to delay its US IPO, and that they were concerned about listing requirements requiring companies to give US authorities information about suppliers, which may create cybersecurity vulnerabilities for Chinese companies’ domestic networks. The crackdown threatens the viability of the Variable Interest Entity (VIE), a legal work-around that Chinese tech firms have used to list on US stock exchanges.

MERICS analysis: “This aligns with the general movement by Chinese authorities towards reining in the big Internet platform businesses,” said MERICS senior analyst John Lee. “Chinese authorities are making it clear that national security and government oversight comes first. At the same time, however, they are tailoring China’s cyberspace regulations to ensure that desirable levels of cross-border data transfer can continue.”

More on the topic: Take a look at the latest additions to our series on digital and tech issues covering the ethics of Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT) and developments in the semiconductor industry in China.

Media coverage and sources:

- Bloomberg: China tech rout deepens as Beijing targets data, U.S. listings

- Globescan Capital: Chinese VIE Structure: Wall Street continues to ignore the risks

- WSJ: Chinese regulators suggested DiDi delay its US IPO

- SCMP: China launches cybersecurity review against three new newly-listed firms

- People.cn:《关于依法从严打击证券违法活动的意见》

Reactions to the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary show a world divided on China

The facts: The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 100th anniversary celebrations on July 1 – and in particular some martial terms in Xi Jinping’s speech – were widely read by European and US media as evidence of Beijing’s assertiveness in the context of deteriorating relations with the West. However, global reactions to the centenary were not uniform. Several world leaders, including the Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, sent notes of congratulations, underlining the polarized state of China’s foreign relations with liberal democracies on the one hand and a coalition of friendly countries on the other.

An especially important country in this coalition is Russia. Two days before the CCP centenary, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin signed an extension to the 20-year-old Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship.

28 countries were brought together by China on June 25 for a virtual “Asia and Pacific High-level Conference on Belt and Road Cooperation.” During this slimmed-down and region-specific version of previous Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) forums, two new partnership initiatives were launched – one for “green development” and another for Covid-19 vaccine cooperation.

What to watch: The differing views of China in so-called advanced economies and the Global South deserve further scrutiny. A Pew Research poll published June 30 showed resurgent positive views of the US in “advanced economies” and broadly negative views of China. The poll surveyed opinion in only “advanced economies,” neglecting low and middle-income countries that Beijing has targeted through active “Global South” diplomacy and the BRI.

MERICS analysis: The dominant narrative among the US and its allies, that China is a threat to international stability, is not shared worldwide. The assumption in the West is that the backlash to China is a universal phenomenon. This position fails to acknowledge that China’s rise and the BRI are well-received in many low- and middle-income countries, as well as among autocrats that benefit from relations with Beijing.

More on the topic: On our focus topic the CCP at 100, we have published various analyses over the past few weeks - texts, podcasts, videos and, not least, our latest MERICS Paper on China: “The CCP's new century: more economic control, digital governance and national security”. You will find our publications on the topic here.

Media coverage and sources:

- The Diplomat: China Holds Slimmed-Down Belt and Road Conference

- The Washington Post: ‘Heads bashed bloody’: China’s Xi marks Communist Party centenary with strong words for adversaries

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China: Xi Jinping Speaks with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic on the Phone

- 中国一带一路网 (Belt and Road Portal): 习近平同俄罗斯总统普京举行视频会晤 发表联合声明

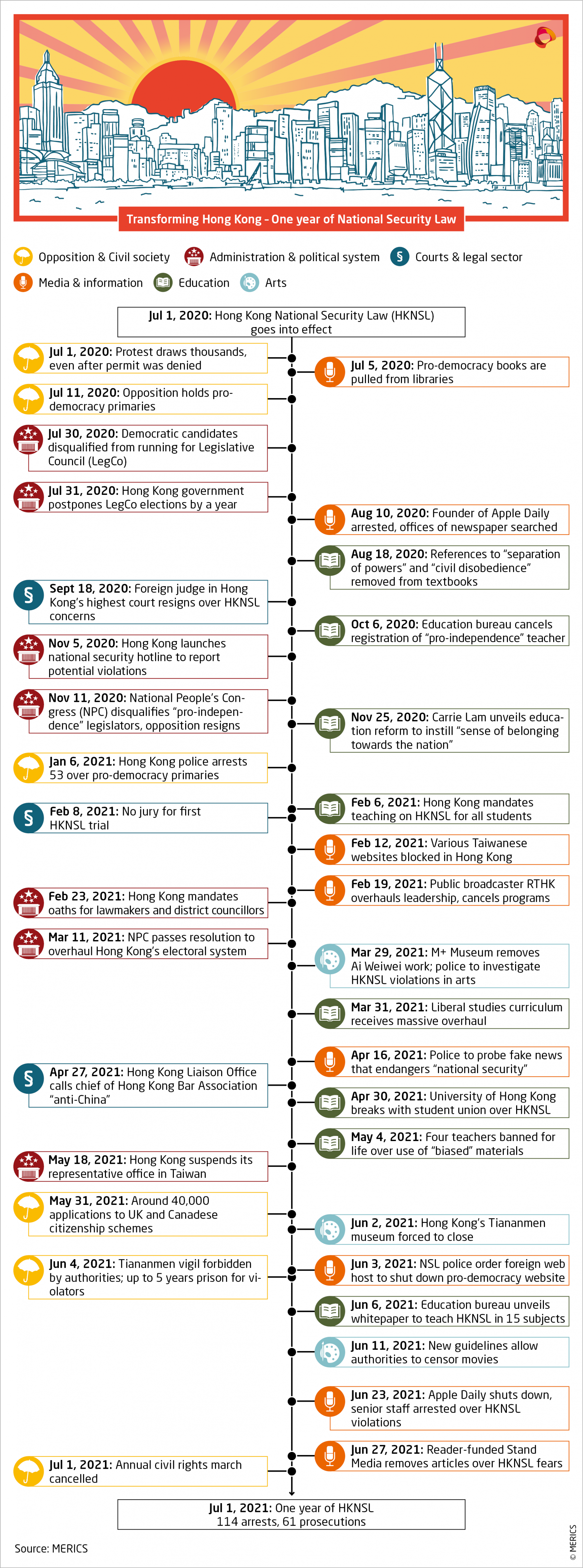

Hong Kong National Security Law – a muted first birthday

The facts: As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrated its hundredth birthday on July 1, the Hong Kong National Security Law (HKNSL) turned one. Hong Kong authorities made sure the centenary celebrations would not be overshadowed by protests there. The city’s annual Civil Human Rights March had drawn large crowds in 2020, but the July 1 event did not take place this year. Its organizer had recently been jailed.

What to watch: For Chinese authorities, the anniversary of the HKNSL marks the first year of Hong Kong’s transition “from chaos to order.” Over the past year, 114 people have been arrested under the terms of the new law – and many more for infringements of other statutes. Hong Kong’s electoral system was recently overhauled, media organizations have been constrained in their reporting or disbanded, and the impact of the HKNSL continues to increase. Just this week, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam pledged new laws to deal with national security risks posed by social media.

MERICS analysis: Without the CCP, there would be no “One Country, Two Systems” – as statements in official media emphasize. The CCP’s big vision for Hong Kong’s future is simple: patriotism and support for the party’s rule are a civic duty. As long as this principle isn't guaranteed in Beijing's eyes, the authorities will continue to roll out new restrictions on the city’s freedoms under the banner of national security.

Media coverage and sources:

- People.cn: 《我们感到无比骄傲和光荣》

- China File: New data show how Hong Kong’s National Security arrests follow pattern

- South China Morning Post: Hong Kong protests: Civil Human Rights Front will not apply for permission to hold annual July 1 march for first time in 19 years

- South China Morning Post: Is Hong Kong’s national security law being weaponised?

METRIX

>1.000.000.000.000

China's foreign currency deposits hit a historic high of more than USD 1 trillion due to the recent export boom. This has created massive headaches for the country’s commercial banks over how to effectively recycle the huge influx of foreign currencies, and in turn how to generate investment returns. Source: Yahoo Finance

VIS-À-VIS: Maria Repnikova on China’s media – “an increase in sophistication of control and adaptability”

MERICS China Briefing spoke with Maria Repnikova, an Assistant Professor in Global Communication at Georgia State University. As part of our series about the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at 100, MERICS talked to her about how China’s media landscape has changed, how the CCP is trying to address a global audience and how Chinese journalists navigate an increasingly fraught working environment.

Questions by Nis Grünberg, Senior Analyst, MERICS

How has Xi Jinping changed the party-state’s interaction with media?

Control has been expanded significantly in different areas – from internet governance to traditional media and ideology. Under Xi, we have seen an increase in the sophistication of control and in adaptability when it comes to persuasion and propaganda. Discussions in Western media and policy communities often focus on censorship and surveillance, but in parallel the party has adapted how it engages with messaging. It uses social media and messaging in a much more creative, playful, emotional way. It has shifted from ideology to a more creative engagement that can even conceal its own involvement.

What does China’s media landscape look like today?

Some people imagine China’s media landscape to be monolithic and dominated by party-owned companies. But over the last 20 years there has been a diversification of outlets, with the party loosening subsidies and allowing some competition and advertising. That has led to new semi-commercial outlets that coexist with party-owned ones – though the party still owns a majority stake in these younger players. We have also seen a rise in the number of citizen journalists and individual voices. Their reporting is often more accurate and livelier. During the pandemic, citizen journalists covered the lockdown, medical-equipment shortages and other community issues. Then there are the social media platforms, but they are not independent either. They are private companies that have been coopted by the party – loyal gatekeepers when it comes to political content.

How do journalists navigate these proliferating red lines?

Journalists playing a constructive role in society is an important idea, one that appears in how China presents itself abroad, especially in the developing world. When it comes to navigating red lines, one of the techniques journalists have been using is alignment with the party's agenda. During the anti-corruption campaign, a lot of journalists from semi-commercial or more critical outlets took up the agenda already being pushed by the party, making their reporting less sensitive. They investigated officials already under investigation.

Also, reporting often offers solutions. During the pandemic in Wuhan, news reports featured critical voices, but often ended with suggestions about how to improve the legal system, accountability or medical care. There is a spirit of moving forward, not looking back. Lastly, the media and the party keep a close eye on social media trends. Media outlets are often savvier, honing in on topics that are rousing interest and trying to cover them before the party has developed an interest of its own.

How good is the CCP at internationalizing the “China story”?

There are several points of friction with this kind of messaging attempt. First, the constructive reporting approach is not really appealing, especially to Western audiences, because it tells a story that's mainly positive and so appears not credible. The second friction is that there are two audiences, one international, one domestic. The aggressive Twitter rhetoric of “Wolf Warrior” diplomats has a more domestic orientation, but it interferes with global audiences. On the positive side, Chinese media are adapting. Media outlets are hiring local reporters and producers – as can be seen in CGTN offices in Nairobi or London, but also in those of China Daily and the Xinhua news agency. These media companies are hiring local talent and over time these journalists could well end up telling stories somewhat differently – if they’re given the space to do so.

Photo credit: James C. Taylor III, Georgia State Department of Communication

REVIEW

The Chinese Communist Party. A century in ten lives by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn and Hans van de Ven (eds; Cambridge University Press, 2021)

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) marked its 100th founding anniversary last week, Beijing pulled out the stops and celebrated in ceremonial splendor. News outlets worldwide covered the event and supplemented their reports with analyses and commentaries about the party’s past, present and future. Many publishers also wanted to mark the anniversary and brought out a slew of books to coincide with it. One remarkable example is “The Chinese Communist Party. A Century in Ten Lives”.

The book stands out because of its focus on individuals’ stories instead of the impersonal party and its apparatus. It presents ten stories about ten people who interacted with the party in ten different decades of the CCP’s history. In the founding 1920s, Dutch Communist Henricus Sneevliet was dispatched from Moscow and helped with the CCP’s inception even though he spoke no Chinese. As the party rose in prominence in the 1940s, the fanatic idealist Wang Shiwei became part of an intellectual rebellion against Mao Zedong’s leadership. In the troubling 1950s, the famous actress Shangguan Yunzhu remained resolutely devoted to the party, despite having been publicly humiliated, severely beaten and forced into manual labor by Mao’s revolutionary Red Guards.

The stories in this collection are rich, compelling and at times poignant. As the authors and editors intended, the book opens a more human perspective onto the history of the CCP. Instead of the usual history of political decisions and struggles for power, the book unfolds the stories of the lived experiences of prominent and lesser-known figures in China this last century. The resulting tapestry of human moments vividly illustrates the complicated, sometimes unpleasant and tumultuous, and always fascinating history of a party that has shaped China and, in doing so, also helped shape the world.

Reviewed by Valarie Tan, Analyst, MERICS

MERICS CHINA DIGEST

MERICS’ Top 3

- NIKKEI Asia: China looks to East Africa for second Indian Ocean foothold

- Yicai Global: AI firms are opening at faster pace in China, as registrations jump 151% in first half

- NIKKEI Asia: US tech giants warn Hong Kong data law could drive them away

Politics, society and media:

- SCMP: National security law: students and university employee among 9 arrested over alleged terrorist plot to bomb streets, courts, transport networks

- The Guardian: Science journal editor says he quit over China boycott article

- CGTN: Over 1.3 billion Covid-19 vaccine doses administered in China

Economy, finance and technology:

- Bloomberg: China’s industrial profits grow at slower pace as costs rise

- Reuters: Growth in China's June services activity falls to 14-month low - Caixin PMI

- SCMP: Economic thought of China’s Xi to be immortalised in newly established research center

International relations: