2. Safe interdependence: Managing economic vulnerabilities

This is chapter 2 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis."

Key Findings

- The supply chain disruptions caused by Covid-19 and the severity of their impact on Europeans’ health and livelihood have heightened existing concerns about Europe’s economic dependence on China.

- China has long set its economic policy on a trajectory of strategically managed interdependence that does not converge with OECD norms, requiring a careful rethink of these interdependencies in Europe.

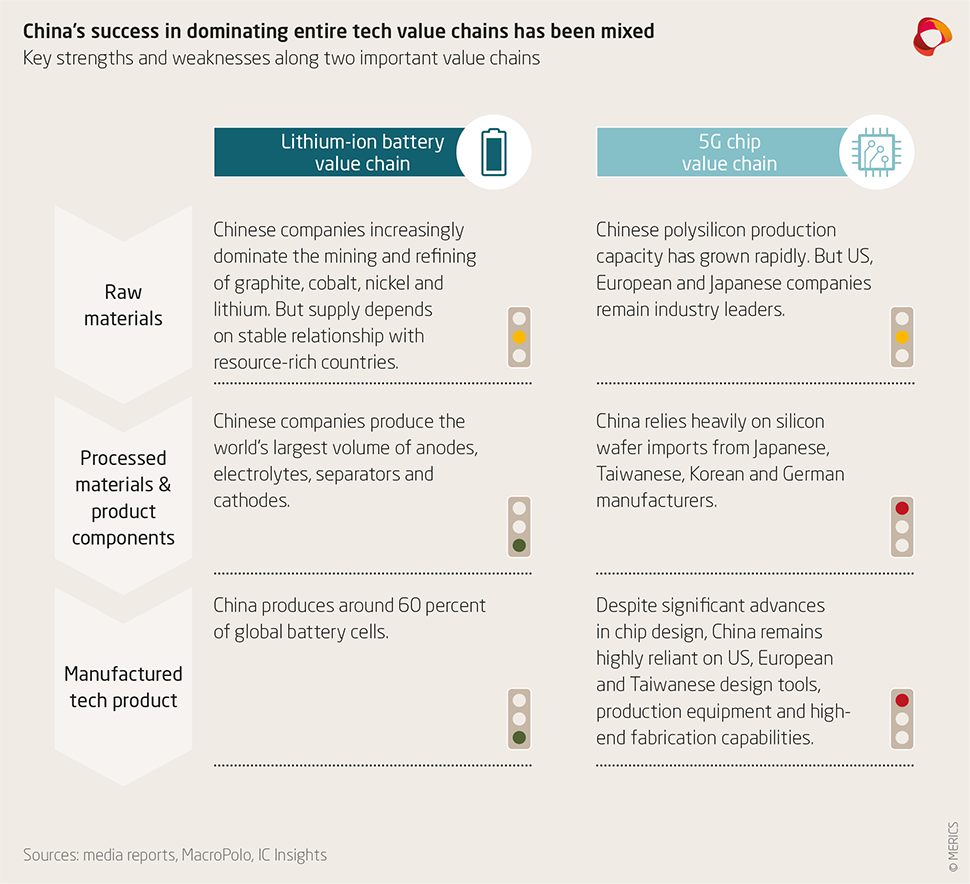

- While China remains a long way from becoming self-sufficient, especially in high-tech industries, in many sectors it has managed to move up the value chain to produce increasingly sophisticated goods for export.

- Europe faces challenging decisions when it comes to securing critical supply chains and assessing the role of Chinese companies in Europe’s ecosystem for emerging technologies.

- The EU’s dependence on China for life-saving pharmaceutical ingredients and technology-powering batteries are weaknesses that could be exploited by China through coercive tactics.

- To handle growing risks of Chinese economic coercion, the EU should follow the lead of East Asian nations and better compartmentalize its relationship from an “economic security perspective.”

1. Crisis lessons: Europe needs to recalibrate economic interdependencies with China

When, in late January of 2020, China’s economy began grinding to a standstill due to the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus, the ripple effects were quickly felt in the rest of the world. Before long, sustained factory closures in China meant European manufacturers faced shortages of crucial products and components from their Chinese suppliers. Europe’s auto and electronics industries were among the hardest hit, but even more concerning were disruptions that carried severe public health implications: Europe experienced shortages in pharmaceutical ingredients and other critical medical supplies imported from China, ranging from personal protective equipment to ventilators, just as the pandemic spread across the region.

The supply chain disruptions caused by Covid-19 and the severity of their impact on Europeans’ health and livelihood have heightened existing concerns about Europe’s economic dependence on China. The pandemic is now widely cited as a real-life case study that has exposed Europe’s trade vulnerabilities and the need to accelerate existing initiatives to increase the EU’s strategic and economic autonomy. Meanwhile, fears that Beijing may exploit European trade dependencies to coerce companies or EU member states to toe the Communist Party line are also increasing, adding to these concerns.

The European Commission has long sought to reduce Europe’s dependence on other countries for critical materials and technologies, as exemplified more recently by its New Industrial Strategy for Europe, launched in March.1 But the pandemic has created a greater sense of urgency, causing many prominent voices to call for an immediate reassessment of the risks of economic dependence on China. EU politicians are now mulling European production requirements for strategic goods and drawing up proposals for the review of EU supply chain vulnerabilities and the diversification of import sources for critical supplies.2 There are widespread calls to strengthen Europe’s “resilience” by diversifying European supply chains that are predominantly rooted in China.

However, it would be rash to jump to the sweeping conclusion that Europe must reduce its interdependence with China in all areas of the bilateral economic relationship. As this chapter’s analysis of three core issues shows, patterns of asymmetry and dependence vary in scope and risk level across different aspects of EU-China economic relations – from overall trade and investment relations and the EU’s reliance on China for critical supplies and products, to Beijing’s attempts to control the value chains of foundational emerging technologies. While acute vulnerabilities in some areas of the economic relationship undeniably pose risks to Europe’s strategic autonomy and thus necessitate a rebalancing of ties with China, Europe’s relative strength in other areas should embolden it to resist Chinese efforts at economic coercion.

China has long set its economic policy on a trajectory of strategically managed interdependence that does not converge with OECD norms. Given the long-term competitive risks this path poses to Europe, as well as the immediate vulnerabilities and potential for exploitation of dependencies for political gains, a careful rethink of these interdependencies is needed to strengthen European resilience. The challenge for Europe will be to settle on a unified and coordinated approach to evaluating and managing EU-China economic interdependencies at both the EU and member-state level.

2. China’s trajectory: managing interdependence to minimize vulnerabilities and create leverage

China’s global importance as a manufacturer and exporter is the result of decades of carefully managed integration into global value chains. Since its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has rapidly cemented its position as a key producer and exporter of many manufactured goods, especially intermediate goods. Initially dubbed the world’s factory due to its abundant supply of low-wage workers, cheap land and relatively lax environmental regulations, China has since moved up the value chain by manufacturing and exporting intermediate goods with increasing value added.3

China’s rise to its position as a global manufacturing hub was driven by targeted state measures that incentivize foreign companies to move their manufacturing (and related know-how) into China while supporting China’s domestic industrial upgrading efforts. China’s industrial policy approach has shifted from prioritizing catching up with foreign manufacturing and technology capabilities to much more ambitious goals. Localizing global supply chains within China, upgrading Chinese industrial capabilities and dominating in emerging technologies from the start are key elements of Beijing’s goal to transform the nation into a globally competitive manufacturing and technology superpower by 2049.

For at least the past 15 years, China’s leaders have focused on indigenous innovation, core technologies and strategic mega projects to manage China’s future interdependence with other countries in technologies. With a web of industrial strategies that have targeted strategic emerging industries and, since 2016, “innovation-driven development,” Beijing has sought to capitalize on a new technological revolution to improve the country’s relative strength and competitiveness. Its most well-known centerpiece, the Made in China 2025 initiative, explicitly pushes for substituting foreign manufacturing components and core technologies in strategic sectors with “indigenously” made alternatives.4

As Beijing actively strengthened the integration of Chinese industry in global value chains, the government also sought to manage and address the risks of interdependencies that result from deeper economic ties.5 It made concerted efforts to vertically integrate Chinese supply chains by reducing the country’s own dependence on foreign manufacturing inputs and technology.6 The continuing escalation of US-China tech tensions have further fueled Beijing’s national security concerns. Chinese companies getting cut off from crucial US-made technology demonstrated to Beijing the urgent need to end its dependence on foreign tech.

While China remains a long way from becoming completely self-sufficient, especially in high-tech industries, in many sectors it has managed to move up the value chain to produce increasingly sophisticated goods for export – and will continue to do so. China’s resulting dominance in the production of new technologies such as lithium-ion batteries, and critical supplies such as rare earths, are increasingly causing concern in Europe.

That is because China’s strengths in these areas are based on an industrial policy approach that builds on strategically managed interdependence. It fundamentally diverges from market-oriented principles and practices in the OECD. That includes the principle of ‘competitive neutrality,’ according to which private and state-owned firms should be able to compete on a level playing field.7 A major economic policy document, issued by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council in May this year, is an important and timely reminder that China’s economic policy-making will continue to pay lip service to the importance of market forces while in reality championing the state-owned sector and strategically aligning the private sector through state intervention.8

Even more concerning, China is increasingly leveraging its importance as a supplier of sought-after goods for economic coercion. There are mounting examples of Beijing threatening European governments and individual companies that are dependent on its products with punishment or outright retaliation for acting against its interests.9

With China’s coercive tactics increasing and unforeseen crises such as the Covid-19 outbreak laying bare the serious risks of economic dependence, Europe will need to systematically reassess certain areas of its economic dependence on China. The deterioration of US-China relations and sweeping efforts to decouple from one another add another layer of urgency: Europe must establish its own position on the risks associated with China’s strategically managed interdependence.

3. Key issues: High-stakes interdependence in trade, critical supplies and high-tech value chains define EU-China relations

European decision-makers still hope to conclude an ambitious investment agreement with China. It is therefore imperative that they weigh the benefits of deeper economic integration and the offshoring of manufacturing against the associated risks. Doubling down on an increasingly asymmetric partnership with a state-led and distorted market economy could have serious negative repercussions for Europe’s long-term competitiveness and economic security. At a minimum, these efforts need to be accompanied by measures to minimize the risks. In addition to negotiating a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the necessary guardrails, Europe faces challenging decisions when it comes to securing critical supply chains and assessing the role of Chinese companies in Europe’s ecosystem for emerging technologies.

Issue 1 – Trade and investment: Mutual dependence and asymmetries

The coronavirus crisis has given rise to a new narrative that Europe is overly dependent on trade with China. However, this narrative does not match with official trade data. These show that, on the whole, the EU single market – not China – is by far the most important trading partner for all EU member states.10 In 2018, the EU single market, on average, accounted for nearly two thirds of total exports of EU member states, whereas China accounted only for an average of 2.4 percent. Of course, trade with China varies across member states. But even Germany, which is generally seen as most vulnerable to Beijing’s economic pressures, exported only 7.1 percent of its total exports to China that year, compared to 59 percent to the EU single market.

Furthermore, this narrative fails to take into account the importance Europe plays for China economically. Europe is not only a key export market for China, it also supplies China with goods that are still indispensable given the country’s industrial upgrading ambitions. From advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment to specialized machinery and tools, China needs European technology and know-how as it pursues its goals. Amid escalating US-China tensions and the continual tightening of US export controls, China may come to rely even more on its European suppliers and partners, as Chinese tech companies urgently search for alternative sources for key components and machinery.

The narrative of economic overdependency, then, may stem from the exposure of individual, large corporates. Germany’s private sector is among the most invested in China, with an automotive industry that relies heavily on sales to Chinese consumers, but various major companies headquartered in other European countries – from Dutch semiconductor equipment company ASM International to British metals and mining corporations BHP and Rio Tinto – also rely on China for significant shares of their global revenue.11 Such corporate dependencies open the door to Chinese retaliatory action against European governments, yet it is worth noting that Beijing has rarely followed through on threats to cut off European companies from the Chinese market.12

Issue 2 – Critical supplies and products: Pharmaceuticals, PPE and rare earths

The coronavirus crisis has also exposed the vulnerabilities of some critical European supply chains that rely considerably on goods or components imported from China. In these specific supply chains, Europe is overly dependent on China, which has implications that go beyond commercial considerations to become a matter of national health or security.

In the medical space, Europe is highly dependent on foreign-sourced active pharmaceutical ingredients (API). Around 90 percent of APIs needed for the European production of generic medicines are sourced from China and India, with India itself 70 percent reliant on Chinese APIs.[iv] China also provides between 80 and 90 percent of the global supply of APIs for antibiotics. When it comes to medical equipment, the EU imported half of its personal protective equipment (PPE) from China in 2018, with an even higher reliance of 71 percent in mouth-nose protection equipment.14

One step further upstream, Europe also depends on China for metals such as cobalt, platinum and rare earths, many of which are critical materials needed for the production of high-tech products, medical devices and military equipment. The EU remains entirely dependent on imports for its rare earth supplies, most of which come from China.15

Already aware of these dependencies in critical areas, the EU had started funding several initiatives to tackle such dependencies long before the coronavirus crisis.16 However, diversifying import sources and repatriating the production of such goods is easier said than done for materials whose production requires large factory sites and causes severe environmental damage. China remains the most competitive environment to produce such materials and, for now, Europe remains vulnerable to any disruptions to these supply chains.

Issue 3 – Emerging technology value chains: Establishing control

China has been particularly keen in its efforts to dominate the global value chains for future technologies, from semiconductors to new energy vehicles and 5G. However, these very technologies have some of the most complex value chains. Fully dominating them would mean controlling the various points at which value is added, from the mining of raw materials, to the assembly or production of various components and the manufacturing of the finished product.

In some areas, China boasts considerable success in taking charge of the value chain from start to end. A good example is the value chain for the production of lithium-ion batteries, which power electric vehicles, consumer electronics and new energy storage solutions.17 Chinese companies dominate the mining and refining of most of the essential raw materials needed for battery production, including graphite and cobalt.18 Meanwhile, China produces the world’s largest volume of midstream battery components, and its leading battery companies, such as CATL and BYD, produce 61 percent of the world’s finished battery cells. Europe, which has a global battery cell manufacturing share of only around 3 percent, is highly dependent on importing battery cells as well as the components and raw materials needed for production.19 Despite EU efforts to scale up Europe’s battery manufacturing capacity, many of Europe’s upcoming local battery manufacturing facilities are still being built by Chinese companies.20 To ensure consistent battery supply, European car giants are actively deepening their partnerships with Chinese battery makers.21

In public debates, China’s dominant global role in foundational emerging technology and the resulting dependence of other countries on China, is often exemplified by Huawei’s dominance in 5G network technology. According to Huawei, its equipment is being used in two-thirds of the commercially launched 5G networks outside of China and it has secured 47 commercial 5G contracts in Europe.22 Yet at the same time, 5G illustrates the significant weaknesses that remain in China’s drive to control tech value chains. Crucial elements needed to build 5G base stations include Field Programmable Gate Arrays, for which Huawei relies on US suppliers Xilinx and Intel. It is also dependent on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which fabricates the 5G chips designed by Huawei’s chip subsidiary using US and Dutch semiconductor manufacturing designs and equipment. Following the tightening of US export controls, Huawei may struggle to procure or produce the chips it needs to build 5G base stations – exposing a major weakness in its technology supply chain.23

4 .EU-China relations: Europe is less beholden to China than most think

The EU is China’s biggest trading partner – it is China’s most important export market, and the source of major direct investment and technological know-how. As such, the EU-China bilateral relationship in trade and investment has long been characterized by mutual economic dependence, rather than one-sided European dependence on China. European and Chinese companies trade, compete and cooperate around the world, while benefiting from investments in each other’s markets.

Certain aspects of the EU-China economic relationship, and certain sectors, reveal imbalances that point to European weaknesses vis-à-vis China. Supply shortages in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic point toward an overdependence on Chinese inputs and imports in certain critical product value chains that make the EU vulnerable in times of crisis. Dependence on China for life-saving pharmaceutical ingredients and technology-powering batteries are weaknesses that could be exploited by China through coercive tactics.

However, more broadly speaking, Europe may be less beholden to China in its trade and investment relationship than recent narratives claim. Its biggest source of economic growth still comes from trade within the EU single market, while China itself is highly dependent on European imports of crucial high-tech machinery and chemicals – key European strengths. When it comes to China’s grasp of technology value chains, specifically, China has made considerable inroads. However, it still retains its own weaknesses and dependencies, often to do with the underlying basic research or manufacturing equipment. The EU therefore should not be overly fearful of economic interdependence with China and should have greater awareness of the strengths that give it leverage over China.

5. Policy priorities: Europe needs to assess vulnerabilities and take action

The coronavirus crisis has brought to public attention the important risks of Europe’s economic dependence on China. While the pandemic should indeed be seen as a wake-up call, it should not lead to sweeping conclusions that economic interdependence with China is one-sided or harmful in and of itself. While the pandemic has demonstrated the risks of relying on global supply chains with heavy input from China, it has also showed the advantages: when it was Europe’s turn to shut down factories as the virus spread beyond China’s borders, China was able to get back to work and resume production, ensuring a continued supply of goods.

What is needed is a thorough assessment of the risks as well as the benefits of economic interdependencies with China. Europe should adopt a more systematic approach and recalibrate interdependence in a way that addresses European vulnerabilities while building on its strengths. This includes the need for concrete and unanimously accepted definitions of which traded goods and technologies are considered “critical.” It also requires the creation of EU-level mechanisms to support policy responses from an economic security perspective. There can be no blanket approach to building “resilient” or “robust” global supply chains, given their complexities. Different types of interdependencies – across different sectors, among specific value chains and individual corporations – require different policy solutions.

When it comes to the overall trade and investment relationship, the EU will have to change course to rebalance trade and investment relations with Beijing towards greater fairness and reciprocity, as negotiated first best options are likely to fail. While the EU should not overestimate China’s lackluster dedication to market reform or Europe’s own relative power, given certain member states’ or sectors’ relatively larger dependence on China, it should not underestimate the power of collective political action.

Based on a comprehensive audit of national and corporate-level dependencies on China, the EU should pinpoint its strengths and weaknesses and identify areas for coalition-building. Should a unified EU stance fail to advance European interests, it should look to its allies beyond Europe to exert pressure in areas where competitive risks from China’s managed interdependence are unbearable. To handle growing risks of Chinese economic coercion, the EU should follow the lead of East Asian nations and better compartmentalize its relationship from an “economic security perspective.” This would allow it to resist political pressure from Beijing while maintaining a stable trading relationship.

Based on EU-level and national-level reviews of strategic industries and specific goods that are critical to national security, the EU should limit its exposure to China through a strategy that prioritizes diversification – and in some cases relocation – of critical supply chains. This will require serious resource commitments to enable the building of manufacturing capacity outside of China. In doing so, the EU should not aim for complete self-sufficiency through reshoring production – this is an unrealistic goal given the complexity of supply chains and China’s considerable manufacturing strengths.

Emphasis should instead be placed on rebalancing away from reliance on a single supplier. In addition to existing plans to stockpile emergency equipment and shore up investment in Europe’s domestic pharmaceutical and rare earth capabilities, the EU should review its other existing trading relationships with allies to identify opportunities for closer cooperation with the aim of reducing dependencies on China in critical, strategic goods. There is also a need for nuanced terminology and strategies so that efforts to strengthen Europe’s supply chain resilience do not slide into trade protectionism.24

To tackle dependencies on China for foundational emerging technologies, new institutional mechanisms fulfilling the functions of an “economic security council” would enable member states and the EU to devise policy responses specifically for issues that lie at the nexus of technology, trade and security. Such mechanisms should be an essential part of the EU’s efforts to constrain the reach of China’s distortive economic and industrial policies; only in this way can the EU ensure that its policies are based on nuanced assessments of both Chinese and European strengths and weaknesses in technology value chains, and that member states are unified in their interpretation of political and economic risk.

To be digitally sovereign, the EU should strengthen support for its European ecosystems for technologies such as 5G, semiconductors, and cloud technologies. At the same time, the EU must upgrade its safeguards to mitigate the potential risks stemming from the inevitable involvement of Chinese companies in European development of future technologies.

Finally, any European strategies to recalibrate global supply chains must be developed in close consultation with European firms, given the difficulties of adjusting complex value chains. Thus far, political rhetoric on the need for supply chain relocations has not yet translated into major corporate action. European companies are expressing concerns over the financial and logistical challenges of adjusting operations – all of which could take years. Continually growing market demand in China also means that many European companies will continue to pursue an “in China for China” manufacturing strategy. The EU must take into account industry representatives’ perspectives in order to conduct realistic scenario-planning and ensure the effectiveness of policy support measures.

- Endnotes

-

1 | European Commission (2020). “A New Industrial Strategy for Europe.” March 3. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-eu-industrial-strategy-march-2020_en.pdf. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

2 | Lange, Bernd (2020). “International trade after the corona-crisis - Business as Usual or Systemic Change?” April 28. https://bernd-lange.de/uploads/bernd_lange/2020/International-trade-after-the-corona-crisis-Bernd-Lange-EN-27042020.pdf. Accessed: June 16, 2020; Fleming, Sam and Michael Peel (2020). “EU industrial supply lines need strengthening, commissioner warns.” Financial Times. May 5. https://www.ft.com/content/5e6e99c2-4faa-4e56-bcd2-88460c8dc41a. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

3 | Garcia-Herrero, Alicia and Trinh Nguyen (2019). “Supply Chain Transformation: The World Is More Linked to China While China Becomes More Vertically Integrated.” Natixis Research. October 9. https://www.research.natixis.com/Site/en/publication/-_JQUR-0gdezsHpW3oZJLosBMLm42dNjkaNv7SfiCFY%3D. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

4 | Zenglein, Max J. and Anna Holzmann (2019). “Evolving Made in China 2025: China’s industrial policy in the quest for global tech leadership.” MERICS Paper on China. July 2. https://merics.org/en/report/evolving-made-china-2025. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

5 | Gewirtz, Julian (2020). “The Chinese Reassessment of Interdependence.” China Leadership Monitor. June 1. https://www.prcleader.org/gewirtz. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

6 | MOFCOM 中华人民共和国商务部et al. (2016). “商务部等7部门联合下发关于加强国际合作提高我国产业全球价值链地位的指导意见 (Guiding Opinions of 7 Ministries Including the Ministry of Commerce on Strengthening International Cooperation to Enhance the Position of Chinese Industry in Global Value Chains).” December 5. http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/fwzl/201612/20161202061465.shtml. Accessed: June 16, 2020; Garcia-Herrero, Alicia and Trinh Nguyen (2019). “Supply Chain Transformation: The World Is More Linked to China While China Becomes More Vertically Integrated.” Natixis Research. October 9. https://www.research.natixis.com/Site/en/publication/-_JQUR-0gdezsHpW3oZJLosBMLm42dNjkaNv7SfiCFY%3D. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

7 | Huotari, Mikko and Agatha Kratz (2019). “Beyond investment screening: Expanding Europe’s toolbox to address economic risks from Chinese state capitalism.” MERICS and Rhodium Group. October 17. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/DA_Studie_ExpandEurope_2019.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2020.

8 | State Council 中华人民共和国国务院 (2020). “国务院关于新时代加快完善社会主义市场经济体制的意见 (Opinions of the State Council on Accelerating and Improving the Socialist Market Economy System in the New Era).” May 18. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-05/18/content_5512696.htm. Accessed: June 20, 2020.

9 | Rosenberg, Elizabeth et al. (2020). “A New Arsenal for Competition: Coercive Economic Measures in the U.S.-China Relationship.” Center for a New American Security. April 24. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/a-new-arsenal-for-competition. Accessed: June 20, 2020.

10 | Poggetti, Lucrezia and Max J. Zenglein (2020). “Exposure to China: A Reality Check.” Berlin Policy Journal. February 26. https://berlinpolicyjournal.com/exposure-to-china-a-reality-check/. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

11 | Reuters Graphics (2020). “European companies' exposure to China.” https://graphics.reuters.com/USA-CHINA-MARKETS-EU/0100900600D/index.html. Accessed: June 16, 2020

12 | Bennhold, Katrin and Jack Ewing (2020). “In Huawei Battle, China Threatens Germany ‘Where It Hurts’: Automakers.” The New York Times. January 16. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/16/world/europe/huawei-germany-china-5g-automakers.html. Accessed: June 16, 2020; Satter, Raphael and Nick Carey (2020). “China threatened to harm Czech companies over Taiwan visit: letter.” Reuters. February 19. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-czech-taiwan-idUSKBN20D0G3. Accessed: June 16, 2020; Shipman, Tim (2020). “China threatens to pull plug on new British nuclear plants.” The Times. June 7. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/china-threatens-to-pull-plug-on-new-british-nuclear-plants-727zlvbzg. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

13 | European Commission (2020). “Dependency of the EU pharmaceutical industry on active pharmaceutical ingredients and chemical raw materials imported from third countries.” Pharmaceutical Committee. March 12. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/committee/ev_20200312_795_en.pdf. Accessed: June 10, 2020; Schulz, Florence (2020). “Europe’s dependence on medicine imports.” Euractiv. March 16. https://www.euractiv.com/section/health-consumers/news/europes-dependence-on-medicine-imports/. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

14 | Bown, Chad P. (2020). “COVID-19: China's exports of medical supplies provide a ray of hope.” Peterson Institute for International Economics. March 26. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/covid-19-chinas-exports-medical-supplies-provide-ray-hope. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

15 | Cole, Laura (2019). “Europe takes on China’s global dominance of rare earth metals.” Euractiv. July 2. https://www.euractiv.com/section/batteries/news/europe-takes-on-chinas-global-dominance-of-rare-earth-metals/. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

16 | European Commission. “Policy and strategy for raw materials.” https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/raw-materials/policy-strategy_en. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

17 | Ma, Damien et al. (2020). “Supply Chain Jigsaw: Piecing Together the Future Global Economy.” MacroPolo. April 13. https://macropolo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Supply-Chain.pdf. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

18 | Patterson, Scott and Russell Gold (2018). “There’s a Global Race to Control Batteries—and China Is Winning.” The Wall Street Journal. February 11. https://www.wsj.com/articles/theres-a-global-race-to-control-batteriesand-china-is-winning-1518374815. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

19 | European Commission (2018). “Li-ion batteries for mobility and stationary storage applications.” EU Science Hub. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/li-ion-batteries-mobility-and-stationary-storage-applications. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

20 | European Commission. “European Battery Alliance.” https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/policy/european-battery-alliance_en. Accessed: June 10, 2020; Lombrana, Laura Millan et al. (2020). “Europe accelerates efforts in the race to dominate EV batteries.” Automotive News Europe. February 20. https://europe.autonews.com/suppliers/europe-accelerates-efforts-race-dominate-ev-batteries. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

21 | Volkswagen Newsroom (2020). “Volkswagen intensifies e-mobility activities in China.“ May 29. https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/en/press-releases/volkswagen-intensifies-e-mobility-activities-in-china-6072. Accessed: June 10, 2020.

22 | Liao, Rita (2019). “Huawei says two-thirds of 5G networks outside China now use its gear.” TechCrunch. June 26. https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/25/huawei-wins-5g-contracts/. Accessed: June 16, 2020; Li, Lauly et al. (2020). “Huawei claims over 90 contracts for 5G, leading Ericsson.” Nikkei Asian Review. February 21. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/China-tech/Huawei-claims-over-90-contracts-for-5G-leading-Ericsson. Accessed: June 16, 2020.

23 | Li, Lauly et al. (2020). “Huawei and ZTE slow down China 5G rollout as US curbs start to bite.” Nikkei Asian Review. August 19. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/China-tech/Huawei-and-ZTE-slow-down-China-5G-rollout-as-US-curbs-start-to-bite. Accessed: August 24, 2020.

24 | Van Tongeren, Frank (2020). “Shocks, risks and global value chains in a COVID-19 world.” Ecoscope. August 25. https://oecdecoscope.blog/2020/08/25/shocks-risks-and-global-value-chains-in-a-covid-19-world/. Accessed: August 28, 2020.

This is chapter 2 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis." Continue with Chapter 3 "Competing with China in the Digital Age" or go back to the table of contents.