6. Engaging in effective geopolitical competition

This is chapter 6 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis."

Key Findings

- In the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, China has expanded its geopolitical clout in old and new geographies and domains. In the years ahead, Europe will increasingly be forced to resist and limit China’s geopolitical power projection.

- Two decades of substantial economic growth, along with a major campaign to modernize the armed forces, have significantly increased China’s power projection abilities, and the CCP has detected a growing number of pockets of vanishing Western influence in the international system.

- Recent years have seen a considerable uptick in China’s deployment of investments and lending to expand its footprint in the Western Balkans, and Beijing’s involvement in the MENA region is rapidly evolving.

- Beijing organizes growing numbers of military drills and maneuvers in the Indo-Pacific, meant both as a show of force and an implied threat to neighbors.

- China is also increasingly moving into new spaces and domains of geopolitical competition, like the Arctic, which is also of considerable geostrategic interest to the EU.

- Although Europe’s relative power vis-à-vis China is limited in many areas, it does not mean that the EU has no leverage or tools to use when confronting China’s geopolitical ambitions.

1. Crisis lessons: China emerges as a geopolitical rival to Europe

In the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, China has expanded its geopolitical clout in old and new geographies and domains. Beijing stepped up its military presence in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait and did not shy away from a confrontation with India at the disputed joint border in Ladakh. China also managed to present itself as a critical provider of Covid-related aid in the Western Balkans and completed work on its Beidou satellite system, expanding its ability to project force in space.

The pandemic has provided Beijing with an opportunity to further expose and exploit vulnerabilities in the already strained Western-dominated global order, taking advantage of the distraction of other countries. It has left onlookers in Europe in no doubt that China will be a force to be reckoned with in the future in virtually all aspects of geopolitical competition – whether in political, economic or military terms.

In becoming a geopolitical actor on the global stage, China will more often than not be in conflict with the norms, principles, and interests of OECD countries. For example, China uses investments and lending on the EU’s doorstep in the Western Balkans to influence the strategic orientation and policy choices of the countries in the region, as Serbia’s rapprochement with China illustrates. China uses a wide range of political and security policy tools, such as defense diplomacy, arms exports, and even military deployments, to increase its footprint in another EU near abroad, the MENA region. By doing so, China is increasingly prepared to clash openly with EU and US interests, for example in Syria. And in what is perhaps the clearest example of geopolitical competition with OECD and European partner countries, China also uses its growing military power projection abilities in the Indo-Pacific to contest the presence and influence of liberal democracies in the region, while a new area of geopolitical contestation between China and the West is already emerging in the Arctic.

Despite the EU’s recent heavy emphasis on becoming a more geopolitical actor and its recognition of China as a “systemic rival”,1 the logic of member states’ engagement with China still has all too often neglected the geopolitical dimension. Maintaining strong economic and commercial relations with China has remained a priority of many European capitals, as decision-makers still hoped that such engagement would eventually lead to China’s (partial) convergence with OECD norms and principles. It took an unexpected event like the Covid-19 pandemic and China’s highly problematic behavior during this crisis, coupled with China’s authoritarian drift under Xi Jinping and its standoff with the United States, for Europe to finally start considering the implications of geopolitical competition with China.

While limited areas of cooperation with China still exist and more might emerge, in the years ahead Europe will increasingly be forced to resist and limit China’s geopolitical power projection in geographies and domains where the EU has relatively little clout itself and to contain these activities where Europe has power or can establish it relatively swiftly. To this end, the EU and its member states will have to integrate their China policy much more explicitly with wider geopolitical considerations and relevant tools in their geopolitical toolbox.

2. China’s trajectory: Beijing’s geopolitical interests will hardly align with those of OECD countries

Since Xi Jinping came to power, China has gradually abandoned his predecessor Deng Xiaoping’s maxim of “bide your time, hide your brightness”, leaving behind a period when Beijing chose to keep a low profile in international affairs. China’s struggle for “national rejuvenation”, which Xi proclaimed first in 2012,[1] is also one for reclaiming its former status of a truly global power by 2049 – the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the PRC. China’s new, assertive geopolitics is driven by two primary convictions.

First, the CCP now feels confident enough in China’s strengths and capabilities – political, economic, and military – and its own political and economic model. Two decades of substantial economic growth, along with a major campaign to modernize its armed forces, have significantly increased China’s power projection abilities. Due to the nature of its one-party system, Beijing is also uniquely able to mobilize and synchronize the activities of all of government, industry, and the military, leveraging economic, security, and foreign policy tools abroad in an integrated way that liberal democracies cannot easily replicate.

Second, the CCP has also detected a growing number of pockets of vanishing Western influence in the international system that it feels China can and should fill as a basis for cementing its global leadership ambitions. This alleged “period of strategic opportunity” of declining Western influence on the international stage is not a new concept, as it was first articulated by President Jiang Zemin at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.[2] However, the notion has gained significant traction among CCP elites in recent years, especially since the financial crisis of 2008 and even more so with the election of Donald Trump and his administration’s retreat from a number of international commitments. The rifts in EU unity that have become more visible since the 2015 refugee crisis and Brexit have also contributed to Chinese assertions that the West is in decline.

The Covid-19 pandemic is seen by Beijing as an opportunity to gain influence in more remote geographies, as other countries remain distracted by their own outbreaks and their economic impact. Given China’s clearly laid out intentions and its perception of a window of opportunity, it should come as no surprise that Beijing is increasingly engaging in geopolitical competition with the United States and Europe. It builds partnerships around the globe and popularizes its own political and economic model, while also trying to take the lead in non-traditional areas of geopolitical competition, like space or cyberspace. This trend, which is likely to continue and speed up in the run-up to 2049, will more often than not put China at odds with OECD countries.

In many instances, the “new type of international relations”,[3] which Beijing is keen on promoting through a more assertive approach to geopolitics and which would see China lead the “reform” of the global governance system, poses a direct challenge to the type of liberalism and multilateralism the vast majority of OECD countries are committed to. While China tries to present itself as a responsible power invested in defending the global order, its actions say otherwise. For example, Beijing has a track record of – directly or indirectly – supporting regimes that the EU and other OECD countries oppose, such as Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria.[4] And in the Indo-Pacific, one of today’s core arenas of geopolitical competition and a lifeline for OECD economies’ global supply chains and exports, China’s growing military power projection is a cause of instability.

At the same time, areas where European and Chinese interests might selectively converge and where cooperation is possible, such as joint peace missions on the African continent in recent years, seem to be shrinking.

3. Key issues: China poses challenges to Europe in the Western Balkans, the MENA region, the Indo-Pacific, and increasingly the Arctic

In the coming years, China will pose the greatest geopolitical challenge to the EU in its near abroad, specifically the Western Balkans, the MENA region, and the newly emerging geopolitical playing field of the Arctic. However, the EU would be ill-advised to only consider geopolitical competition with China in its neighborhood, as Chinese activities are also putting in question freedom of navigation in the Indo-Pacific.

Issue 1 – Western Balkans and the MENA region: A new player

Recent years have seen a considerable uptick in China’s deployment of investments and lending – often channeled through BRI infrastructure projects – to expand its footprint in the Western Balkans.6 China has a vested interest in improving and promoting infrastructure in this underdeveloped region, as the road into the big markets of Western Europe from the Chinese-owned port of Piraeus runs through the Balkans.

China’s perceived “no strings attached” approach to investment, along with parts of its authoritarian governance model, have proven appealing to some countries in the region, like Serbia, while the considerable size of some Chinese loans is threatening to drive others, like Montenegro,7 into a relation of debt dependency with China. This could make these countries more vulnerable to Beijing’s political influence. Moreover, Chinese investments in the EU’s near abroad often do not live up to the norms and standards promoted by the EU and sometimes even help perpetuate corruption in the region. The Budapest-Belgrade railway project is a case in point, with the EU having opened an investigation into the Hungarian government in 2016 for initially not following EU procurement rules.8

Beijing has traditionally had little involvement in the MENA region, but that is changing rapidly. China needs a stable MENA region if it wants to achieve its goals of expanding the BRI and its access to the region’s resources, protecting Chinese citizens and assets, and dealing with terrorist threats originating in the region. The Chinese leadership is also using this growing presence to present itself as an alternative partner for MENA countries, one that is an honest broker with no hidden agenda for the region, unlike Europe or the US.

Over the last few years, Beijing has increased its defense diplomacy efforts in the region, with high-level defense officials from MENA countries visiting Beijing regularly to discuss security cooperation with China. The PLA Navy (PLAN) has visited the region on multiple occasions, both for friendly port calls and to hold joint drills and exercises with local militaries. The Chinese military also maintains a permanent presence in and close to the region, with Chinese peacekeepers deployed in Lebanon, the PLAN patrolling the waters of the Gulf of Aden, and the opening of China’s first overseas military base in Djibouti.

Furthermore, China is becoming a major source of weapons and military technology to the region, often providing the weapons that Western countries refuse to sell, such as armed UAVs.9 In the past, Beijing has also offered to mediate in some of the region’s longest-running and most intractable conflicts, from Syria and Afghanistan to the Israel-Palestine and Saudi Arabia-Iran conflicts.

Issue 2 – China’s neighborhood: Europe can no longer look the other way

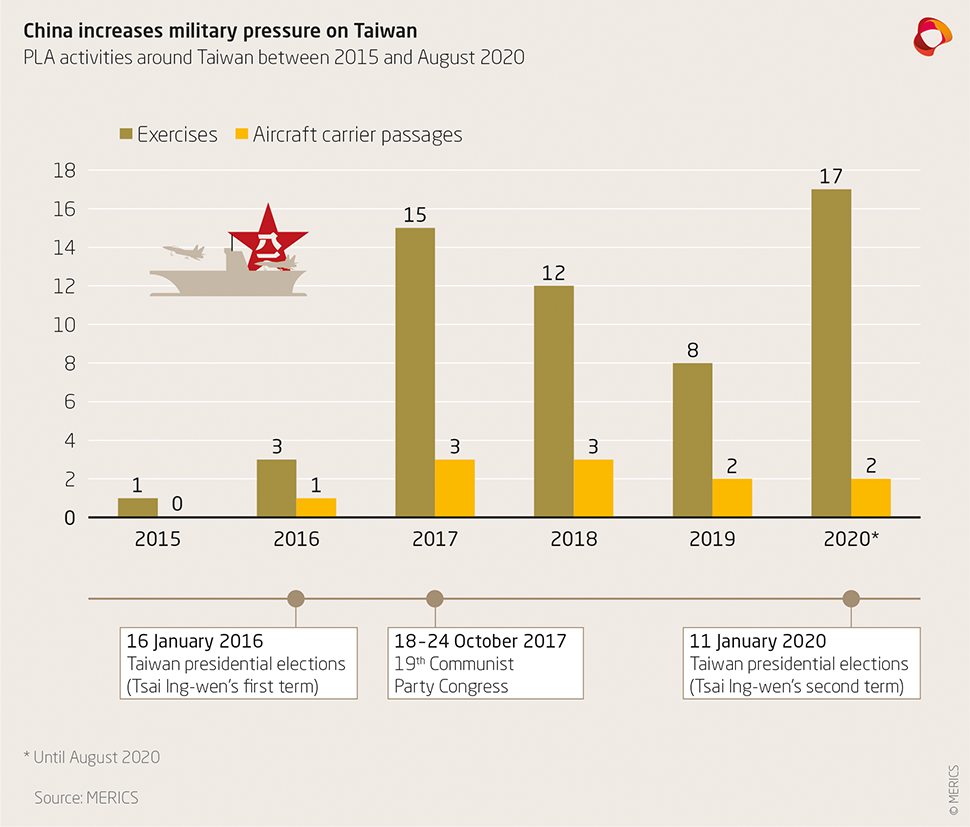

Further afield from Europe, the Indo-Pacific has become a major arena of geopolitical competition between China and the United States. While Europe has mostly taken a backseat with regard to developments in the region, this will not be a sustainable course of action going forward. Recent years have seen an increasingly aggressive Beijing organize growing numbers of military drills and maneuvers in the Indo-Pacific, meant both as a show of force and an implied threat to neighbors. Taiwan is a case in point. Beijing has long maintained that it would prefer to reunify with Taiwan through peaceful means, although it has never ruled out the use of force. While in the past threats from Beijing to use force against Taiwan lacked credibility because of US support for Taipei and the limited capabilities of the PLA, today China’s rapid military modernization has created a new strategic calculus. According to MERICS data, PLA aircraft conducted flyovers and drills around Taiwan at least 15 times between January and August 2020.10 And it is not only the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) that has stepped up its presence near Taiwan. The PLAN also regularly conducts drills in waters near Taiwan, and China’s newest aircraft carrier, the Shandong, sailed through the sensitive Taiwan Strait in late December 2019.11

Beijing has similarly increased its presence in the South China Sea, building military installations in the disputed Spratly and Paracel Islands, deploying Coast Guard ships – which have been under the direct control of the Central Military Commission since 201812 – to escort survey vessels, engaging in naval standoffs with Malaysia and Indonesia, and confronting US Navy vessels conducting freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in the region.

China’s activities in the Indo-Pacific pose three principal challenges to European interests. First, Europe has a vested interest in protecting stability and freedom of navigation in the area, as key global trade routes traverse the South China Sea. Second, the increasing tensions between the United States and China should also be of concern to the EU, as they could result in a NATO ally (and NATO partners in the region) engaging in military action against China. Third, China’s activities pose direct challenges to international law and the international multilateral order, which the EU has pledged to uphold.

Issue 3 – The Arctic: Making the rules

China is also increasingly moving into new spaces and domains of geopolitical competition, like the Arctic. This region is also of considerable geostrategic interest to the EU. Calling itself a “near-Arctic state”, China incorporated the Arctic Ocean into the BRI in 2017, underlining its ambitions in the region.13 Despite having no claims to sovereignty, Beijing has developed legal positions on key legal and normative issues in the Arctic, aiming to shape debates on issues such as rights to navigation, access to resources, and the application of relevant international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), from the start. The expansion of China’s transportation and resource exploitation-related interests in the Arctic is likely to bring with it an increase in Chinese military power projection in the area, which might also be enabled by China’s increasingly close military relationship with Russia.

4. EU-China relations: The EU must limit China’s geopolitical drive where necessary

As the EU aspires to greater strategic autonomy and geopolitical clout, China has started to feature more frequently and prominently on Brussels’ agenda. However, long-standing trends and dependencies have meant to date that most member states are still focusing on maintaining close economic and commercial ties with China while skirting the more difficult political and systemic issues – often due to fear of retaliation by China.

Chinese actions in areas of significant geopolitical interest to the EU and heightened tensions between China and the US will force Europe to position itself more clearly. Indeed, as China increasingly engages in geopolitical competition in its bid to become a leading global power by 2049, a growing number of voices argue that Europe needs to push back harder against some of China’s behavior on the global stage if it wants to become and remain a relevant geopolitical actor in this new multipolar world.

Doing so, however, will require a realistic assessment of the EU’s relative power vis-à-vis China when it comes to the most pressing geopolitical challenges. In the Western Balkans, where China uses BRI-linked economic tools to expand its footprint and influence, the EU still enjoys relatively high power when compared to China, although its reputation has been damaged by unfulfilled enlargement promises and a lack of “self-advertisement”. Europe remains the largest investor in the region and accession to the EU is still the ultimate goal of most Western Balkan countries. However, the EU has not invested enough resources in “selling” itself effectively, often being outmaneuvered by China, which has invested less and yet gained substantial political capital with elites in the region. It is high time for the EU to contain some of the most problematic Chinese activities in the Western Balkans, such as building non-sustainable infrastructure or encouraging authoritarian tendencies.

Facing China in the MENA region will require a mixed approach by the EU, as the EU’s power is currently lower. On certain issues, a “support and leverage” strategy would be called for, where European and Chinese interests converge. This is the case, for example, concerning counterpiracy operations or participation in UN peacekeeping operations to maintain stability in the region. Cooperation would also be possible and even desirable when China engages in or promotes development or infrastructure projects in the region that align with European norms and standards and that can help to reduce poverty and inequality in the region.

Beijing’s behavior in other areas, however, would require the EU to resist and limit China’s inroads into the MENA region, as they are detrimental to European interests and ultimately security. Examples include Beijing’s support for authoritarian regimes through exports of restricted weapons systems and surveillance technology and China’s growing power projection in the Mediterranean.

In the Indo-Pacific, the EU’s relative power is low. The EU has no military presence in the region and, since the UK’s exit from the EU, France is the only remaining member state able and willing to deploy its navy to the Indo-Pacific to conduct FONOPs. Besides, tensions in the region remain a low priority for many member states. Therefore, this region calls for a “resist and limit” strategy by the EU.

Three EU member states – Denmark, Sweden, and Finland – are Arctic states, and several others are Arctic Council observers, making China’s growing role in the region an issue of relevance for the EU as well. While there are opportunities for cooperation with China in Arctic affairs, there are also clear risks, given the divergence in norms and principles between China and the EU. While Europe’s relative military power vis-à-vis China (and its partner Russia) is low, its geographic position gives Europe the opportunity to push back against China’s attempts to shape the norms and standards that will govern behavior in the Arctic in the future.

5. Policy priorities: The EU needs to raise its China game with partners

China’s actions in the Western Balkans, the MENA region, the Indo-Pacific, and “new geographies” of geopolitical competition, like the Arctic, are among the most pressing geopolitical challenges the EU currently faces. To contain China’s actions in the Western Balkans, the EU must provide a more credible path to EU accession for countries in the region and more actively promote and facilitate access to EU investment and financing sources. The EU should also support relevant actors in the Western Balkans to adequately assess Chinese loans and investments before they are accepted.

On certain issues, the appropriate EU logic of action may also be one of “engaging and shaping” China. Where China’s investments and projects align with EU norms and standards, cooperation should be considered. Europe should also use these opportunities to share best practices and promote European norms and approaches to infrastructure and investments.

The same goes for the MENA region. Overall, however, as Europe’s power is lower, the EU must focus on making China a constant talking point with MENA countries, leveraging its normative and diplomatic power to persuade and pressure MENA countries to resist those Chinese activities that would be most detrimental to their relations with the EU.

Since the EU’s presence in the Indo-Pacific region is limited and its relative power is lower than that of China, it is left with signaling its disagreements with Chinese policies and activities in the region in high-profile ways and resisting them where possible. Resisting China’s behavior in the Indo-Pacific will require, first and foremost, cooperation with like-minded states. This should not be limited to the United States but also include other countries in the region whose values and interests in this space converge with the EU’s, such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, Taiwan, India, or Vietnam, among others. With a view to China’s evolving role in the Artic, EU member states should urgently establish close coordination and possibly even a working group that can help to coordinate EU measures aimed at containing China’s role, where necessary.

Overall, it is high time for Europe to rethink how it wants to position itself in a world of increasing geopolitical competition. Although Europe’s relative power vis-à-vis China is limited in many areas, it does not mean that the EU has no leverage or tools to use when confronting China’s geopolitical ambitions.

- Endnotes

-

1 | European Commission and HR/VP Contribution to the European Council (2019). “EU-China – A Strategic Outlook.” March 12. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

2 | Xinhua (2012). “习近平:承前启后 继往开来 继续朝着中华民族伟大复兴目标奋勇前进” (Xi Jinping: build on the past and prepare for the future, continue to march forward courageously towards the goal of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation). November 29. http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2012-11/29/c_113852724.htm. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

3 | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2002). “Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at 16th Party Congress on Nov 8, 2002”. November 18. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/3698_665962/t18872.shtml. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

4 | Xinhua (2013). “中美新型大国关系的由来” (The origins of the new type of Sino-US great power relations). June 6. http://www.xinhuanet.com//world/2013-06/06/c_116064614.htm. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

5 | Hemenway, Dan (2018). “Chinese Strategic Engagement with Assad’s Syria”. December 21. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/chinese-strategic-engagement-with-assad-s-syria/. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

6 | Holzner, Mario and Schwarzhappel, Monika (2018). “Infrastructure Investment in the Western Balkans: A First Analysis”. European Investment Bank. https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/infrastructure_investment_in_the_western_balkans_en.pdf

7 | Barkin, Noah and Vasovic, Aleksandar (2018). “Chinese ‘Highway to Nowhere’ Haunts Montenegro”. July 16. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-silkroad-europe-montenegro-insi/chinese-highway-to-nowhere-haunts-montenegro-idUSKBN1K60QX. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

8 | Beesley, Arthur, Byrne, Andrew and Kynge, James (2017). “EU Sets Collision Course with China over ‘Silk Road’ Rail Project”. February 20. https://www.ft.com/content/003bad14-f52f-11e6-95ee-f14e55513608. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

9 | Balas, Alexander (2019). “UAVs in the Middle East: Coming of Age”. July 10. https://rusi.org/commentary/UAVs-in-the-Middle-East-Coming-of-Age. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

10 | MERICS research

11 | Lee, Yimou and Blanchard, Ben (2019). “China sails carrier group through Taiwan Strait as election nears”. December 26. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-china-election/china-sails-carrier-group-through-taiwan-strait-as-election-nears-idUSKBN1YU0H0

12 | Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (2018). “中共中央印发《深化党和国家机构改革方案》” (The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China releases the "Plan on Deepening the Reform of Party and State Institutions). March 21. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-03/21/content_5276191.htm#1. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

13 | Xinhua (2017). “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative”. June 20. http://www.china.org.cn/world/2017-06/20/content_41063286.htm. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

This is chapter 6 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis." Go back to the table of contents.