How games can help think tankers develop and test policy ideas

Policy games are a valuable resource regarding a diverse range of policy issues. They can be a tool to shed light on future developments. To realize their potential, clarity of objectives, careful choices on key design questions, and a conscious handling of recurring challenges are key.

Why and when to use policy games

Policy games help analysts work though the viability of solutions to policy issues. They allow think tankers to explore how different developments and choices may interact. This simulates the kind of human decision-making that plays a critical role in such policymaking, especially when a limited group of stakeholders interact strategically.

Offering a "safe-to-fail” environment, games are particularly useful in analyzing scenarios that involve risky decisions or confrontational dynamics, given the potentially devastating cost of ill-informed strategies in the real world. They also help convey knowledge or skills like negotiating.

Chinese nobles and generals played such games as many as 4000 years ago, while modern wargames were developed in 19th-century Prussia. Today, disciplines including psychology, behavioral economics, business management and military studies, regularly use games.

In the policy sphere, think tanks in the US stand out, with some hosting initiatives such as the Wilson Center’s Serious Games Initiative or the Gaming Lab at the Center for a New American Security. In Europe, among other initiatives, the annual Körber Policy Game explores foreign and security policy issues and among other initiatives the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) has designed a game on the political economy of conflict and stabilization.

Designing your game – how to get started.

Fundamentally, games can serve either of two purposes: to analyze, or to educate and inform. While these two goals are often complementary, clarity about the relative priority of these different objectives is critical to designing a game appropriately.

Game designers face a host of choices. The GPPi publication “Gaming the Political Economy of Conflict – A Practical Guide” covers the process of developing and playing games. Here are some essential considerations:

- Defining the scenario: Scenarios provide the framework for game dynamics, setting the stage and defining key actors, relationships and context. Game designers face trade-offs between realism, engaging play and analytical utility. They may choose fictional scenarios to reduce political sensitivities and players’ preconceptions about real-world cases. Or they might use limited fictionalized elements in a real-world framework, as in the GPPi political economy game, which aims to capture a complex social landscape through archetypical actors. Even the most “realist” game designers can’t avoid massive simplification, which creates distortions that such limited fictionalization may alleviate. Dynamic elements like event cards, or a predefined script that is gradually revealed can drive the scenario forward, as in the Ko rber Policy Game.

- Choosing the players: Policy games can involve many types of players, from representatives of real-world figures to thematic experts, generalists or even lay audiences. Games for education and outreach, like “The Fiscal Ship,” which informs people about the US federal budget, suit lay audiences. Generalist policymakers can also benefit from educational games. Thematic experts may be better at mimicking the behavior of specific actors, although they may have trouble dropping their detached, analytical style and immersing themselves in a role. Games with high-level representatives, such as the Ko rber Policy Game, benefit from players with a deep understanding of the motives and behavior of those they represent. Designers should be aware that such participants’ real-world agendas may affect gameplay.

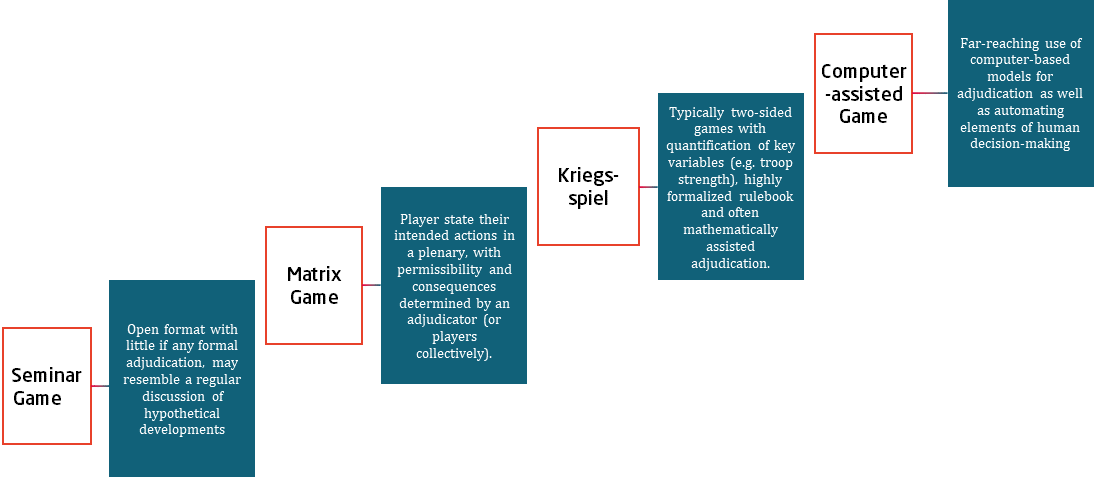

Choosing the right level of game rigidity: Rigidity describes the extent to which fluid human interactions are structured in the game. This can be through formal rules and procedures that prescribe the scope of action for players or through authoritative decision-making by an adjudicator. The degree of rigidity greatly affects the “look and feel” of an exercise and therefore is a key aspect in different types of games. Drawing on wargaming literature, the table shows four archetypes, with rigidity increasing from left to right.

Designing your game – preparation is key.

Successful policy gaming requires tailoring a game design to its purpose. Here are some key considerations for setting up your own game:

- Manage time constraints: In-depth games that enable a thorough exploration of complex interactions and policy situations take time. How will you keep participants engaged ? Perhaps split the game into several sessions ororganize the session away from their regular workplaces.

- Choose the right materials: These influence participants' attention and actions. Ensure materials are self-explanatory and easily and quickly digestible. The participant's level of knowledge must be considered in designing the material. To maintain a level playing field avoid information disparities among participants. Could facilitators help answer questions or prevent a group from getting bogged down in details or veering off topic?

- Assess the knowledge participants bring: Participants’ prior knowledge impacts the outcome – especially in games for analytical purposes. Mismatched expertise may lead to insufficient or biased interaction. However, gathering a mix of experts and / or generalists requires careful facilitation to ensure effective collaboration and communication.

- Share insights from policy games: Transparency in design and game outcomes offers public access to lessons learned so the broader community can benefit from the experiences and methodologies in the gaming process.

Further readings

- Enbaye, Gelila; Hensing, Jakob; Rotmann, Philipp (2024): “Gaming the Political Economy of Conflict – A Practical Guide”, GPPi.

- Lee, Vivien; Schuele, Finn; Sheiner, Louise (2019): "The Fiscal Ship as a Teaching Tool", Brookings Institution.

- Parkes, Roderick, and McQuay, Mark (2021): “The Use of Games in Strategic Foresight. A Warning from the Future”, DGAP.

- Perla, Peter P., and E. D. McGrady (2011): “Why Wargaming Works.” Naval War College Review 64, no. 3: 111–30.

Gelila Enbaye

Research Associate,

Global Public Policy Institute

Gelila Enbaye is a research associate at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) contributing to its work on peace and security. She interested in the Horn of Africa and the intersection of political economy and conflicts. She is also a Think Tank School fellow where she looks into the potential of futures-thinking in peace mediation.

Jakob Hensing

Research Fellow,

Global Public Policy Institute

Jakob Hensing is a research fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin, where he focuses on the intersection of economic and security policy. His interests include the implications of a global economy increasingly shaped by power and security considerations as well as political and economic dynamics in violent crises and stabilization efforts.

Sarah Pagung

Programme Director for International Affairs,

Körber-Stiftung

Sarah Pagung is a Programme Director for International Affairs at Körber-Stiftung, where she is in charge of the Berlin Foreign Policy Forum and the Körber Policy Game. Her research focuses on Russian foreign, security and information policies as well as on German-Russian relations. Previously, she worked at the German Council on Foreign Relations. Sarah holds a PhD in political science from Free University Berlin.