Beijing takes aim at Airbus and Boeing’s dominance

COMAC’s new single-aisle jet could see the Chinese company break the Western duopoly in China and then in markets further afield, argue Max J. Zenglein and Gregor Sebastian.

China’s new C919 single-aisle passenger jet could hail the end of Airbus and Boeing’s global duopoly. After nearly 15 years of development, state-owned Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) delivered the country’s first homegrown passenger jet to China Eastern Airlines in December 2022. Airbus and Boeing can expect only a slow erosion of their supremacy over the large-jet market– for one, the C919 will need some time to prove its competitiveness. But they will have to brace for an eventually very different global market.

COMAC’s domestic market-share looks set to climb steadily

The C919’s market entry is a symbol of China’s technological rise and a source of national pride. A rival to the best-selling A320 and 737, the aircraft should enable China’s largely state-owned aviation sector to meet the government target of reaching 10 percent domestic market-share by 2025. Production glitches or safety issues aside, COMAC´s domestic market-share looks set to climb steadily in a huge and increasingly protected home market, with the company at some point reaching the scale to brave the step into foreign markets and global competition.

Boeing and Airbus currently have more than 10,000 commitments for orders on their books, most of them for narrow body aircraft. They are the bread-and-butter models for manufacturers, accounting for around 60 percent of all jets. Russian contenders – the Tupolev Tu-204 and Tu-214 and the more recent Irkut MC-21 – have over the past quarter century tried to break the US-European domination of the market for single-aisle aircraft. But they can at best occupy a stable, albeit tiny niche, having racked up a few hundred domestic orders.

The size of China’s market gives COMAC an essential home advantage

Given the high development costs, small production runs are not economically viable. This was the key reason for the consolidation of aircraft manufacturing in Europe and the USA over the past few decades. But the size of China’s domestic market gives COMAC an essential and lucrative home advantage. Boeing estimates that China will need 6,500 narrow-body aircraft between 2016-2035, a quarter of global demand. It’s likely that orders from Chinese airlines will no longer be tidily divided between Airbus and Boeing as COMAC gains ground at home.

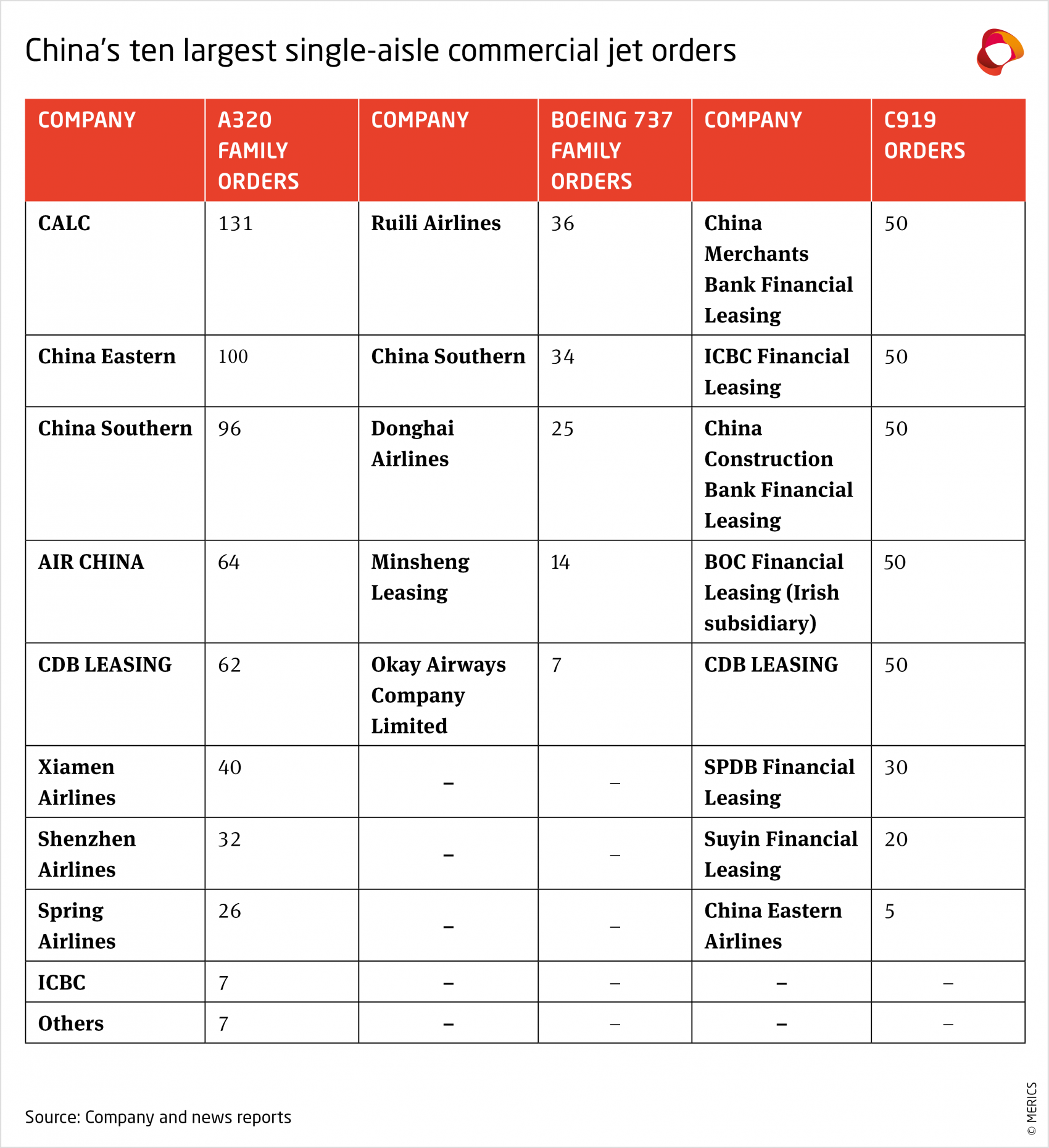

China Eastern is planning to put the C919 into service in spring 2023 and orders for the aircraft are now pouring in. Some 300 orders were placed during the Zhuhai Airshow in November 2022, bringing COMAC’s order book (including letters of intent) to 1081. But COMAC has every reason to ensure a slow market shake-up to ensure the quality and performance of every C919 that enters daily operations and to provide airlines with adequate maintenance support. The company knows that rushing it could be catastrophic for its – and China’s – aviation industry.

This means that there is still room for Airbus and Boeing in the Chinese market. Both companies have expanded their operational footprint in China, including final assembly and R&D centers. With a targeted production of 150 C919 per year, China’s fledgling commercial aviation industry for some time will not be able to stem demand on its own. But it will continue to profit from official support and rivals’ own goals – Airbus and Boeing could find certification becoming more troublesome and the latter has been tarnished by the 737 Max-debacle.

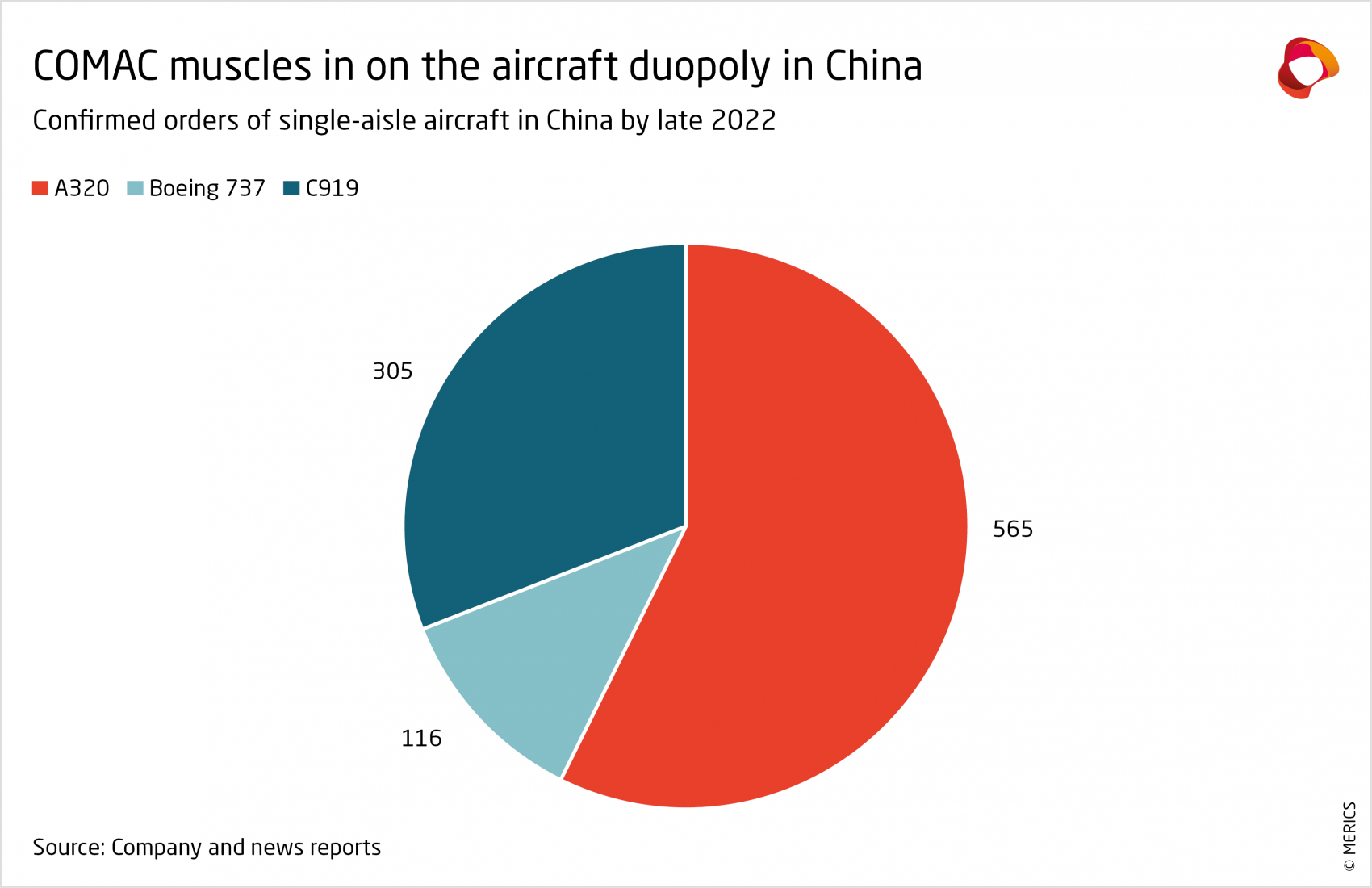

Confirmed Chinese orders even suggest the duopoly is becoming a triopoly to the detriment of Boeing rather than Airbus (see chart). The C919 is the end product of a highly integrated global supply chain. But orders for the aircraft are almost exclusively domestic. China’s state-owned airlines and financial institutions are responsible for most of them. The only foreign buyer is GE Capital Aviation Services, which opted for 20 jets. Thai airline City Air and Germany’s Chinese backed start-up PuRen went broke before the first C919 was delivered.

But this orderbook should not be seen as a weakness. Backed by strong industrial policy and serving a sector dominated by state-owned enterprises and a large domestic market, the C919 appears to be in a good position to advance China’s strategic objectives in aviation. Even if the C919 is less efficient or technologically advanced than the competition, the political aims of China’s state-owned airlines will likely outweigh such operational deficiencies. In an already highly politicized industry, this will further complicate doing business for Boeing and Airbus.

But changes look set to be gradual also because China’s airlines are accustomed to operating Western aircraft. The country’s big three, China Southern, Air China, China Eastern, have placed 294 orders for Airbus’ A320 family and Boeing’s B737 – and only 20 each for the C919. Aviation deals look set for some time to remain useful political sweeteners when Western leaders visit Beijing. The USD 17 billion agreement for 140 Airbus aircraft signed during German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit in November will not be the last example of this custom.

But this should not let Western politicians and executives forget the ambition of China’s political leadership for COMAC. Airbus and Boeing face losing market share in China because of it. If the C919 performs as promised in China over the next few years, the next area of competition will be in third markets outside of China, Europe and the US. Only if the C919 can gain this international foothold will it really become a success. The risks are high, but given China’s industrial-policy successes in other areas, Airbus and Boeing better buckle up.