Beyond Made in China 2025 – China’s dream of broad-based industrial greatness

Beijing wants to become a manufacturing powerhouse in all sectors, say Alexander Brown and Max J. Zenglein. Ten years ago, it was content to aim high in just ten industries.

In 2015, Beijing launched its industrial policy initiative “Made in China 2025” (MIC25) with the aim of transforming the country from a low-cost manufacturing hub into a global leader in high technology. After ten years of paying particular attention to ten critical sectors, Chinese companies have established themselves as globally competitive technology leaders in railway equipment, electric vehicles, and power equipment, but remain dependent on foreign technology in some of the most sophisticated areas, such as advanced IT, aerospace and aviation, biopharma and high-performance medical devices.

Nevertheless, MIC25 has triggered a technology and innovation boom, enabling China to dramatically reduce its dependence on imports. According to the MERICS Trade Dependency Database, the number of products it sourced mainly from the US and/or the EU halved from 351 in 2000 to 177 in 2022. While achieving technological leadership was the ultimate goal of MIC25, the development of Chinese-controlled choke points within global value chains was an added bonus – in 2022, the US and the EU were dependent on China for the import of 953 product categories, three times more than at the turn of the millennium.

In light of mounting geopolitical tensions, the goals of MIC25 have expanded beyond the conventional industrial policy framework to encompass a broader national security strategy centered on industrial supremacy. Although the term 'MIC25' has almost disappeared from policy documents, its ten priority sectors — ranging from new materials and smart manufacturing technology to transportation equipment — have been incorporated into China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021 to 2025). While Western countries are seeking to reduce their dependencies in order to boost their economic security, China is intent on maintaining, if not expanding, its position in global manufacturing.

Beijing sees advanced technology as crucial for industrial competitiveness

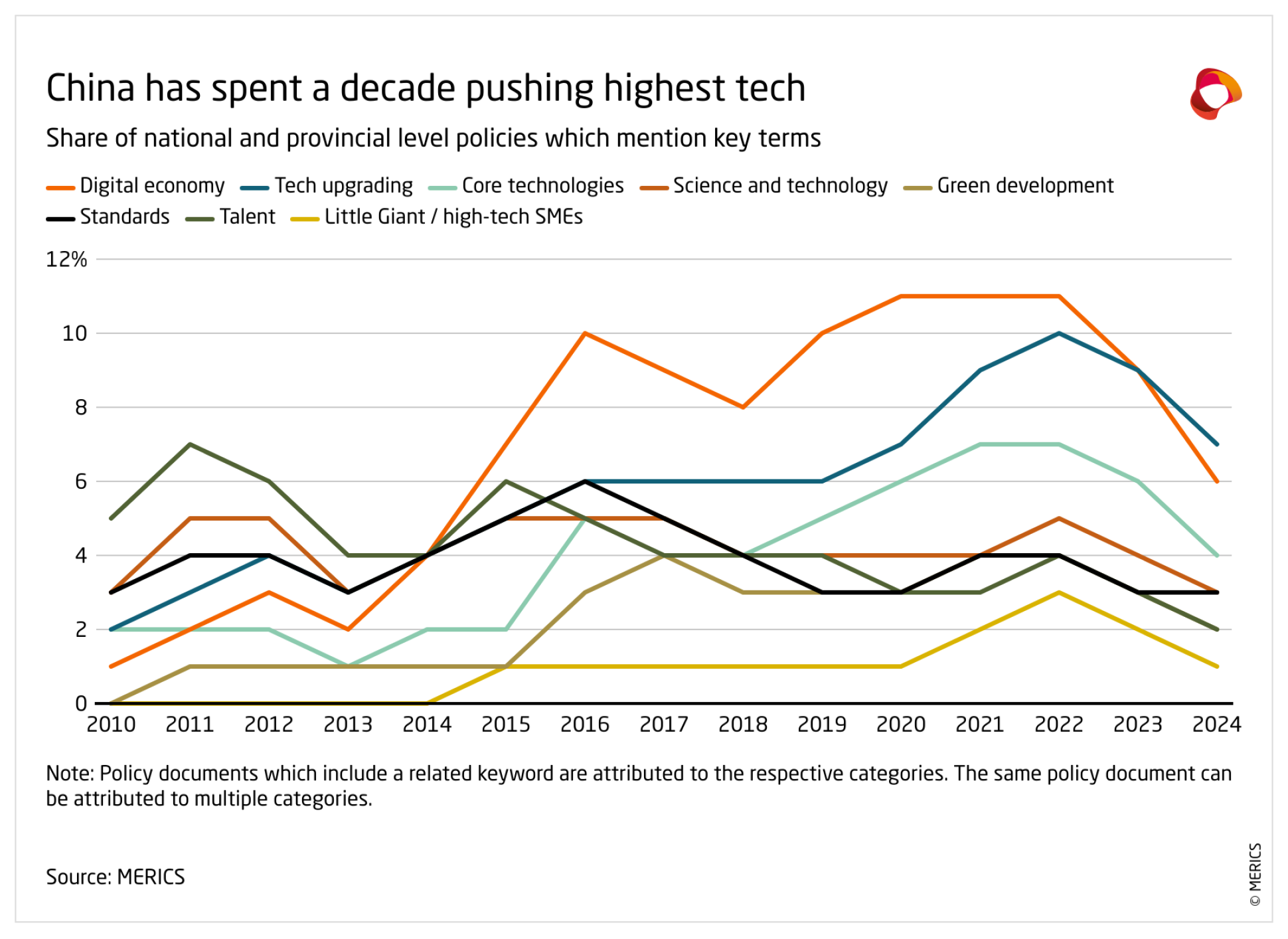

A strong and capable manufacturing ecosystem is seen as key to enhancing economic resilience and strategic leverage. While MIC25 set specific targets for each of its priority sectors, China’s modern industrial policy has evolved into a comprehensive initiative aimed at developing a robust industrial base and ecosystem across all sectors and positions in the value chain. The policy is now more focused on the broad-based strengthening of manufacturing and the leveraging of cross-sectoral technologies, meaning China is competing with both advanced and emerging economies.

China has started to promote the widespread adoption of advanced technologies such as 5G, AI and green technology to boost productivity in a variety of industrial sectors. Beijing considers these to be a single “general purpose technology” that can enhance productivity across the board. Furthermore, the priority sectors outlined in MIC25 form the basis for upgrading industries. Advances in communications equipment, operating systems and software, clean technologies, new materials and biotechnologies can create new opportunities for enhancing productivity, security and quality in other sectors.

China’s manufacturing base is central to the “Chinese style modernization” pursued by Beijing. Its focus on technological upgrading and leveraging high-end technology continues with the concept of “new productive forces”, which Xi has placed at the heart of policymaking since 2023. When setting the long-term economic roadmap for the country, the Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in 2024 placed particular emphasis on this concept, underlining the need for China to take in innovative technologies such as AI, new materials, and quantum technology.

China has broadened its industrial policy and made it an expensive endeavor

This “horizontal” industrial policy has become central to achieving sector-specific targets – not only to help the Chinese economy move up the value chain, but also to extend the competitiveness of traditional industries. The deployment of advanced technologies also generates domestic demand for them, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle that enhances industrial competitiveness further. This approach requires the strengthening of the industrial ecosystem through talent cultivation, standards development, and boosting smaller companies. (The “Little Giants” initiative, launched in with MIC25, has identified 15,000 particularly innovative small and medium-sized enterprises).

But this state-directed technological push is an expensive endeavor that carries a high risk of making resource allocation more inefficient. Domestically, the approach has socio-economic side effects. Although China’s economic reforms and liberalization over the years have raised living standards for the middle classes, Beijing’s recalibration of China’s economic growth model, which is centered on manufacturing and technology, has dampened household sentiment and consumers’ willingness to spend. Beijing has yet to reconcile its objectives with the expectations of China’s middle classes.

China’s leadership shows no inclination to rebalance the economy towards consumption and is willing to accept negative domestic and global consequences as it pushes ahead with its manufacturing-centered objectives. But Beijing will at some point need to address growing domestic and international side effects. These include domestic socio-economic tensions, growing trade surpluses with developed and emerging economies, and the geopolitical competition over technology. “Made in China 2025” may have had a good run, but the growth model it initiated may soon be put to the test.

This analysis was made possible with support from the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.