Charting a risky course: The People’s Bank of China further eases monetary policy

The People’s Bank of China has begun easing monetary policy to respond to slowing economic growth, falling producer prices, and peak bond repayments. The success of this round of monetary easing depends on the allocation of funds to relevant companies and the effectiveness of heavy-handed restrictions on capital flows.

In response to slowing economic growth, falling producer prices, and peak bond repayments the People’s Bank of China has begun easing monetary policy. On January 15, the PBOC lowered banks’ required reserve ratio (RRR) by half a percentage point to 14 percent. It will be reduced by another half point on January 25. The central bank governor, Yi Gang, has said that there is room for further reductions and the cuts will be paired with policies that incentivize lending to small and micro enterprises. Yi also said he expects the cuts to release 1.5 trillion CNY into the banking system.

This round of monetary easing can only generate long-term positive benefits if two conditions are met: state banks must allocate a large enough proportion of the released funds to the relevant private companies. Second, strong outflow restrictions which can insulate the Chinese economy sufficiently from US rate hikes are necessary. Otherwise, the easing could lead to an even bigger accumulation of bad debt by state-owned companies and could result in damaging capital outflows.

State banks must be incentivized to lend to the private sector

With peak amounts of debt maturing in 2019, providing liquidity is necessary to protect big corporates with weak cash flows from default. But for the easing to also generate growth in the real economy it must reach credit-starved sectors. If not, the easing will only postpone an urgently needed resolution of problems in the financial sector without strengthening the economy’s ability to service debt.

The Chinese financial system allocates a disproportionate amount of new lending to unproductive investments. This becomes visible by looking at the relationship between new credit and GDP, the second of which is consistently smaller, meaning that debt is increasing at a faster pace than the ability to service it.

Domestic debt levels have risen steeply across all sectors of China’s economy – in 2018, total credit to non-financials exceeded 250% of GDP, compared to 150% before the global financial crisis struck a decade ago.

Since the beginning of 2017, the government has waged a partially successful deleveraging campaign. Positive achievements include moving off-balance-sheet shadow finance products back on to banks’ balance sheets. This is now clearly visible in credit data; the growth of bank lending is increasingly outpacing that of off-balance sheet financial products. Yet, the overall campaign has yet to see credit growth fall below nominal GDP growth. (See also our blog post: Policy in China still puts growth before deleveraging)

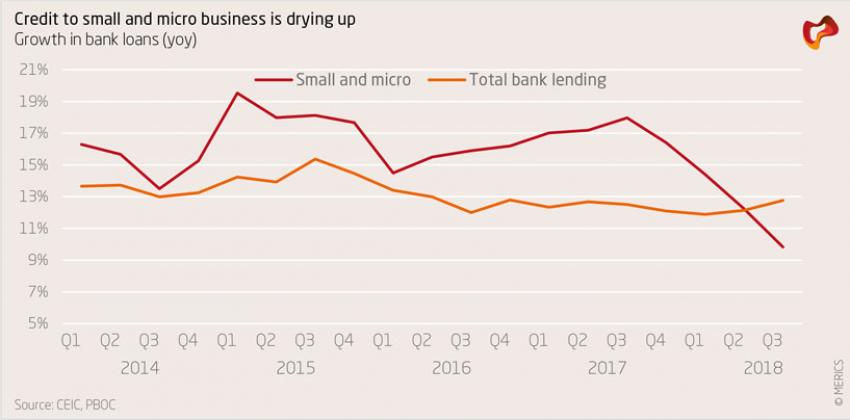

For small and micro enterprises, which already were neglected by the financial system, the deleveraging campaign brought about more difficulties in accessing financial opportunities. Under pressure to contain risks, banks directed the lion’s share of their lending to larger entities which are perceived to be more reliable when it comes to repayment. In the first quarter of 2018, outstanding bank loans to small and micro enterprises grew at 14.4 percent. By the third quarter, growth had fallen to 9.8 percent. Meanwhile, overall bank lending remained almost unchanged, growing at 12.9 percent.

This sector is an important factor in the Chinese economy. Tightening credit conditions in the sector limit the abilities of potentially lucrative smaller businesses to take off or expand, which will hamper the growth potential of the economy. By injecting credit into the sector, the Chinese government tries to reduce the pressure. The PBOC now incentivizes state bank lending to the private sector by giving banks that lend sufficiently to smaller enterprises more room to set their own interest rates. This will be very difficult to accomplish as large institutions difficult to reform.

Capital controls are necessary

Interest rates in the United States and China have decoupled, and the rapidly increasing US rates are a very serious problem for China. The success of the easing program therefore also rests on heavy-handed restrictions of capital flows.

The US Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates, which are now close to China’s central bank rates. The US Fed’s December 2018 rate hike took its benchmark funds rate to 2.4 percent, further hikes are possible.

The return on some financial assets is now greater in the United States than in China. One example is the one-year treasury rate. Additionally, perceived lower risk is driving investors to the United States. and away from China. The CNY/USD exchange rate, which the PBOC manages, appreciated by 5 percent in 2018, indicating lower demand for the Chinese currency. As the interest rate differential expands, the CNY will come under further pressure. This in turn increases the risk of capital flight, as investors try to move their wealth out of China to seek higher returns.

Capital flight is a self-reinforcing herd phenomenon, which means that the initial wave of outflow increases the incentive for further capital movement. This could result in more money leaving the country than the PBOC initially injected, which could severely destabilize the economy. Unless capital controls are strong enough, the risk of this scenario will increase as monetary policy becomes looser.

Success hinges on policy alignment

The Chinese economy faces a large amount of separate problems, many of which the central bank is tasked with solving. The biggest issues on the central bank’s agenda are growth, financial stability, price stability and the value of the currency. The problem with being faced with so many difficulties at once is that when the central bank targets one variable, another is bound to be adversely affected.

To make monetary policy implementation effective in this difficult environment, other government agencies must align their policies with those of the central bank. State banks’ lending practices must change to prioritize lending to SMEs, and various government entities need to be involved in restricting cross-border financial flows. If coordination fails, the risk is that the monetary easing will be downright counterproductive, leading to further credit build-up and capital flight.

The article is part of the latest issue of the MERICS Economic Indicators, a project monitoring China's economic development.