In China, returns on investment are often returns on political decisions

Foreign investors are increasingly active on Chinese financial markets. Maximilian Kärnfelt says they need to be aware that returns on investment are often returns on political decisions.

High investment returns, the opening of new channels for funds and the underweighting of Chinese financial products in Western’ portfolios means that an increasing number of global investors are putting money into China’s financial markets. But the Chinese financial system and its political constraints demand these investors take a different approach to Western markets. They have to understand elite politics and international relations to thrive.

Foreign participation in Chinese markets is still low in absolute terms, but increasing rapidly. Attracting foreign capital has been a government priority. The inflow of funds supports economic growth, supplies the market with foreign currency and helps the management capital flows to ensure exchange rate stability. It also raises market discipline by attracting experienced investors who may be better at providing the best projects with capital.

The Chinese government in recent years created many new investment channels and expanded existing ones – such as the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors that allows licensed foreign investors to trade securities on mainland stock exchanges. It also made it easier to operate in China – the most notable examples being the Hong Kong Stock and Bond Connect trading programs and the green light for fully owned subsidiaries of foreign banks.

Foreign appetite for Chinese stocks and bonds

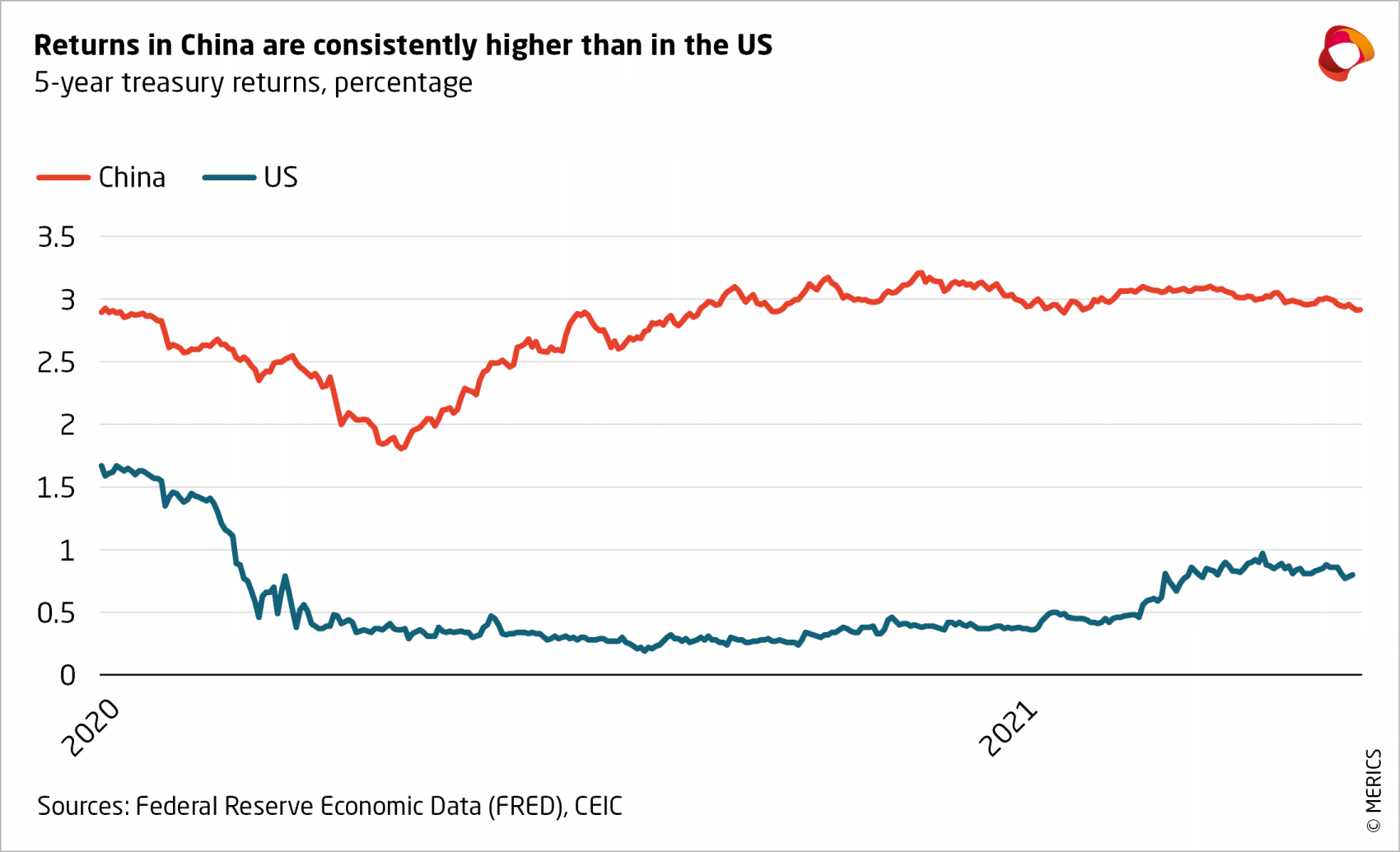

Investors have rushed to make use of these new opportunities to benefit from the better performance of the Chinese market. China’s faster economic growth has led to consistently higher financial-market returns than Western markets over the past years. Take government bonds: a Chinese 5-year treasury currently produces an annual financial return about two percentage points higher than the equivalent US government bond and its risk rating is quite similar – Standard & Poor’s rates the Chinese bond a solid A+ and the US paper AA+.

The biggest conduit, Stock Connect – which allows international investors in Hong Kong and mainland Chinese investors in Shanghai and Shenzhen to trade securities on each other’s stock exchanges – has seen unprecedented volumes. Since the beginning of 2021, Hong Kong-based investors on average have bought and sold 118 billion CNY of Chinese securities on the two mainland exchanges every day, a 29.7 percent increase from 2020 levels.

Foreign participation in the Chinese bond market has also reached new peaks, more than doubling since April 2019, when Chinese bonds were first included in global indices. Foreign investors increased their holdings of renminbi bonds for 27 straight months and now own more than 3.15 trillion yuan – about 385 billion euros – of Chinese fixed-income securities . And there is still room to grow: foreigners owned 3 percent of Chinese A-shares and 2.4 percent of bonds in 2020, compared with levels of around 40 percent in the US.

Economic fundamentals are not always decisive

But foreign investors need to be aware of the fact that China’s economic performance – and the financial returns it promises – is heavily influenced by political decisions. The government is currently pushing through financial-stimulus efforts – such as liquidity injections and reserve-requirement cuts – to support businesses and sustain the economy If Beijing were to roll back stimulus measures, share prices will be strongly affected.

The stock-market crash of 2015 should be an example foreign players keep in mind. Before the crash, the government had been encouraging citizens to participate in the stock market. Huge numbers of retail investors joined the market, quickly drove prices up, then cashed in their gains. After the ensuing crash, the government imposed trading freezes on many stocks, banning stockholders from selling. In addition, foreign investors’ ability to repatriate profits could be constrained if the CNY came under pressure and Beijing limited capital outflows.

Government intervention can also hit companies directly and seemingly out of the blue. Alibaba had planned to list Ant Financial in what was meant to be a 30 billion USD IPO, the world’s largest ever. Enormous sums of cash had built up in Hong Kong in anticipation, but in the end the IPO did not take place. Chinese authorities withdrew their approval for the share sale after Alibaba’s CEO Jack Ma criticized the government’s financial regulators.

The hand of the government also moves the bond market. Chinese corporate debt levels are very high and ever more companies are defaulting. According to the Bank for International Settlements, corporate debt rose 65 percentage points in the last decade and is currently running at 155 percent of gross domestic product. A recent report by S&P found that only 6 percent of property developers that it tracks meet the Chinese central bank’s credit criteria.

But a company’s ability to repay its creditors is strongly affected by its relationship with the government. Whether creditors can recover their money is often not determined by underlying financials. A number of well-connected or systemically important companies – like the conglomerates Huarong, HNA and Evergrande – recently came close to default. But in the end they could secure credit from state banks to refinance their debts. The political importance of a company says more about whether it will default than its credit rating.

Another political factor is foreign policy. If Beijing is at diplomatic loggerheads with another government, companies from that country can at least temporarily encounter a more difficult business environment in China. These conflicts have not yet affected financial services, perhaps because portfolio flows are much smaller than the trade in goods and because China does not want to deter further investment. But they are a possibility.

Because of the Chinese government’s ability to take swift action, investments in China are subject to more political risk than in Western markets. Managing this requires understanding of both Chinese elite politics and of China’s foreign relations. Investors need to pay attention to how policies may affect markets, and to the political connections of stock and bond issuers. Even if returns in China are higher than elsewhere, investors need to beware that they could still suffer losses for political reasons beyond economic fundamentals.