The digital Yuan will only lend a minor boost to internationalization of the currency

Maximilian Kärnfelt argues that China’s digital currency will further its goal of internationalizing the yuan. But there won’t be a snowball effect. This is the second and last part of our series on China's official digital currency. Read part one here.

Fearing that US financial sanctions against its banks and restrictions on access to the SWIFT global payments system are no longer unthinkable, Beijing is accelerating its efforts to internationalize its currency. So that China’s companies might one day pay – and be paid – in yuan, not dollars, around the globe, the central bank has launched a digital currency, the DCEP, which will function as payment system. Chinese officials claim going digital will boost international use of the yuan, but they could well be disappointed. Payment infrastructure is not a bar to the yuan’s global popularity – the problem is its limited convertibility.

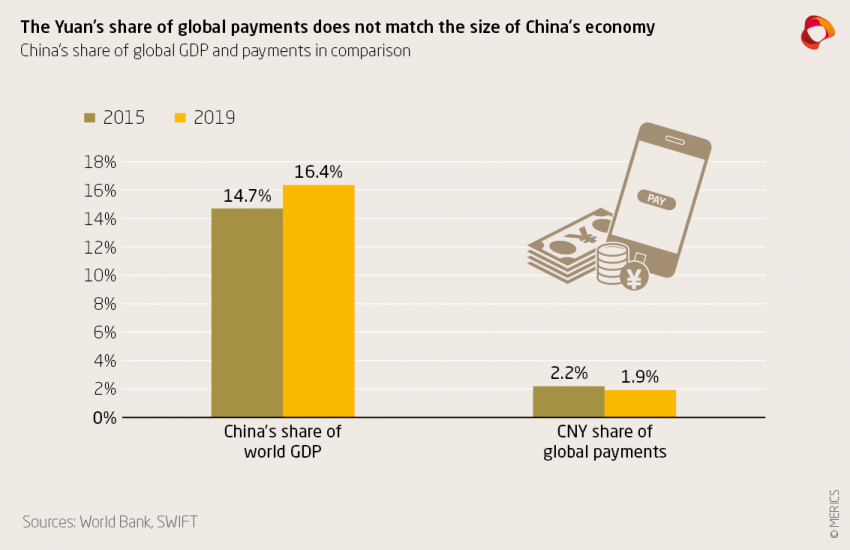

Internationalizing the yuan is a logical move. China is vulnerable to financial sanctions because its overseas trade is dependent on dollars. Most of its cross-border transactions are settled in US dollars – or euros, pounds and yen. Only around two percent of international transactions cleared on SWIFT are settled in CNY and China’s CIPS payment system is still very small, about 0.3 percent the size of SWIFT. Internationalization has long been a goal of the Chinese state, but the popularity of the CNY has not grown much in the past decade.

China wants to insure itself by reducing dollar reliance

Officials in Beijing know that Iran is the example of what can befall dollar-dependent countries disliked by the US. In 2012, the country was subjected to various US financial sanctions, including the blocking of Iranian banks from SWIFT. It was quickly under serious economic pressure, with stagflation, falling growth and depreciation. To sustain employment and cushion its export sector, Iran was forced to devalue its currency. After this, economic growth returned, but Iran’s external purchasing power was significantly reduced.

Even though similar sanctions against China are not very likely since they would affect the US as well, it is not surprising China wants to insure itself by reducing its reliance on the dollar. Internationalization of the currency is once more frequently mentioned in the Chinese debate. For example, in September a commentary arguing that digitalization was needed to break the dollar-monopoly was published in China Finance, a journal run by the central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). More officially, Fan Yifei, deputy governor of the PBOC, in 2018 said the digital currency then in development would help yuan internationalization.

Currency digitalization does not make up for flaws of the physical Yuan

But such talk also defies logic as it implies that the reason for the relative unpopularity of the CNY is due to its not yet having been digitalized. Are we to believe that the enormous discrepancy between China’s share of the global economy and its share of global payments will close once digitalization is complete? No, the weights holding down the old physical CNY will be just as heavy for its digital iteration – and they are very much of China’s own design.

The advantages the DCEP has over regular bank transfers seem rather minor. Firstly, transactions will be cleared faster than traditional bank transfer. And, secondly, investors will likely be rushing to own the world’s first digital currency, anticipating appreciation as a consequence of technological progress. But if there are policies in place that deliberately reduce foreign interest in making transactions in the first place, nothing much will change.

Foreign access to CNY-denominated investment remains restricted

And there are plenty of such policies. Foreign access to CNY-denominated investments is still restricted. China maintains capital controls on outwards investment, restricting the amounts citizens can move abroad. Property rights are highly questionable – in principle the Chinese government has the right to claim assets on national security grounds. Financial reporting is restricted and encumbered, fraud and bad economic news can go undiscovered for years. China’s exchange rate policy is opaque, which means the dollar value of a CNY investment may fluctuate greatly entirely as a result of the whims of the Chinese government.

These policies serve China’s economic model well. They provide China with stability and give the government oversight and control over the economy – crucially, they give China control over employment. By controlling the international use of its currency, China can keep the yuan from appreciating. If China removed all the above policies, demand for CNY would increase dramatically. The goal of internationalization would be reached – but the yuan would appreciate significantly and lead to potentially heavy job-losses in the export sector.

If the US were to ever to warm to the idea of financial sanctions against banks and SWIFT for doing business with China, Beijing would have to reverse some of these policies to truly promote its own currency. If barred from using the dollar, China would have to create offshore currency pools big enough for foreigners to draw on when financing purchases. And it would need to improve its financial system so that foreigners could be persuaded to receive large payments in CNY. But this would have little to do with the DCEP – a very laudable technological advance, it will not lead to a jump in the popularity of the CNY.