Grandstanding or sincere? China’s move to join the CPTPP

Dismissed as grandstanding by skeptics, Aya Adachi says China’s recent application to join Asia-Pacific’s newest and most liberal free trade club could well be the real deal.

China’s recent application to join Japan, Australia, Malaysia and eight other states in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) has been dismissed as grandstanding by skeptics but can also be regarded as sincere: it shows that China recognizes it is dependent on stability in free trade – and that it must up its game to maintain it. After concluding the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with 14 other Asia-Pacific nations in November last year and trying to finalize the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with the EU a month later, Beijing is pushing to join yet another mega-agreement as part of its effort to integrate China into the world economy.

CPTPP goals stand in contrast to China’s track record with trade agreements

Embracing the CPTPP puts China in a proactive position of strength. Rather than being passive and potentially seeing itself increasingly affected by an expanding CPTPP, skewed trade flows and geopolitical dynamics, Beijing is doing its best to influence developments – if the CPTPP partner states let it into the three-year-old club. That is a big if: Australian Trade Minister Dan Tehan said China would only be able join if it convinced every member of its “track ¬record of compliance” with its trade agreements and World Trade Organization commitments.

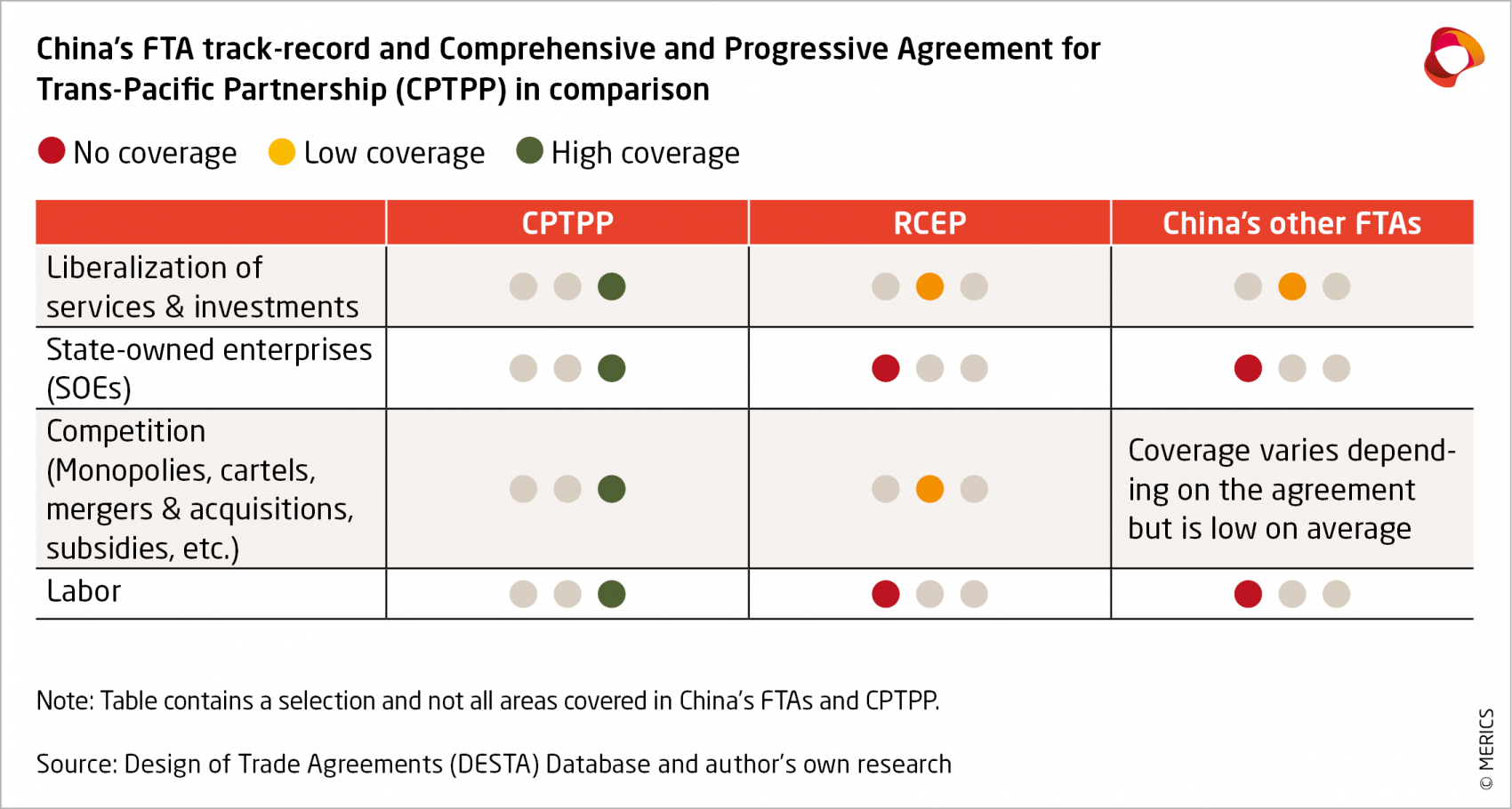

The skeptics are right that CPTPP’s goals for the liberalization of services and investment, and market regulation to ensure competition and open public procurement stands in contrast to China's track record with other free trade agreements (FTAs). CPTPP is considered one of the most technical agreements of this type, with high standards, including substantial environmental and labor provisions, transparency requirements and an unparalleled scope for liberalization. The commitments China has agreed to in order to seal the RCEP and other FTAs are below the levels of coverage of the CPTPP (see table).

China’s bet that it can secure special treatment is far from absurd

But even founding members of the CPTPP have been granted exemptions. With Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam, CPTPP brings together very diverse economies. As many arguably have little in common, give-and-take in the form of exemptions was essential to reach a deal: Japan was granted transition periods for reducing remaining tariffs on agricultural products; Vietnam and Mexico, which have a big state sector, were able to negotiate exceptions from rules for SOEs. So China’s apparent bet that it can secure special treatment of some kind is far from absurd.

China also has great leverage in that it can offer unprecedented access to its market. With an average unweighted most-favored nation tariff rate of 7.6 percent and high restrictions in investment and services still in place, CPTPP members would enjoy privileged access to China’s economy, the largest trade and supply-chain partner for many. CPTPP members have the rare opportunity to incentivize Beijing to commit to high standards, reform public procurement and adopt other forms of market regulation. China’s commitments would exceed those in the RCEP – and Chinese policy makers could use them as a catalyst for more reform, in line with recent adjustments in intellectual property and foreign investment.

But even if China agreed on paper to liberalize its economy, adapt regulations and commit to domestic reforms, its practical implementation of the agreement could tell a different story. As China's accession to the WTO has shown, implementing requirements to successfully transition and gain market economy status have fallen short and cast doubt on China’s intentions. Similar questions about feasibility would likely have been raised by the EU in the course of CAI negotiations, had tit-for-tat sanctions not derailed final steps towards the conclusion. With cause for mistrust, CPTPP members would likely require China to address existing compliance issues and focus on questions about enforcement rules.

China’s accession to the CPTPP cannot be ruled out

China’s greatest challenge will be to persuade all eleven CPTPP members to admit it, as new members can only join with unanimous approval. And therein lies the crux: reactions from CPTPP members have so far been mixed – Malaysia and Singapore have welcomed China’s application and signaled support, New Zealand, Japan, Mexico and Australia have shown more caution. "We need to determine whether [China] is prepared to fulfill the high standards" required by the trade pact, said Japan's Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Hiroshi Kajiyama. Canada has stayed neutral, pointing to the CPTPP accession procedures – to which Taiwan’s CPTPP application less than a week after China’s will add some drama.

China’s accession to the CPTPP cannot be ruled out. Countries in the region were pragmatic towards China in past trade agreements. The TPP, as it was proposed a decade ago, included the US and was meant to counter Beijing. Growing concerns about China mean countries in the region are exploring other ways of protecting their interests – a supply-chain initiative (between Australia, India, Japan), Indo-Pacific strategies, domestic economic-security adjustments. So, they might yet come to see CPTPP as a way to get China to commit to stricter trade rules – and that trying to control China by excluding it is no longer appropriate.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily reflect those of the Mercator Institute for China Studies.