Staying united is the best way for the EU to reduce its trade vulnerabilities on China

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

European countries on average have a hundred times more leverage on China through the EU than when acting alone. François Chimits says the bloc needs to do more to reduce China’s hold.

China was dependent on imports of just 33 types of goods from the 27 individual EU member states in 2022 – that’s an average of 1.2 per country compared with a dependence on 120 products when all shipments are aggregated as a single EU trading bloc. This data from the MERICS Trade Dependency Database (MTDD) shows that EU countries typically have a hundred times more leverage over China when acting through the EU than when acting bilaterally.

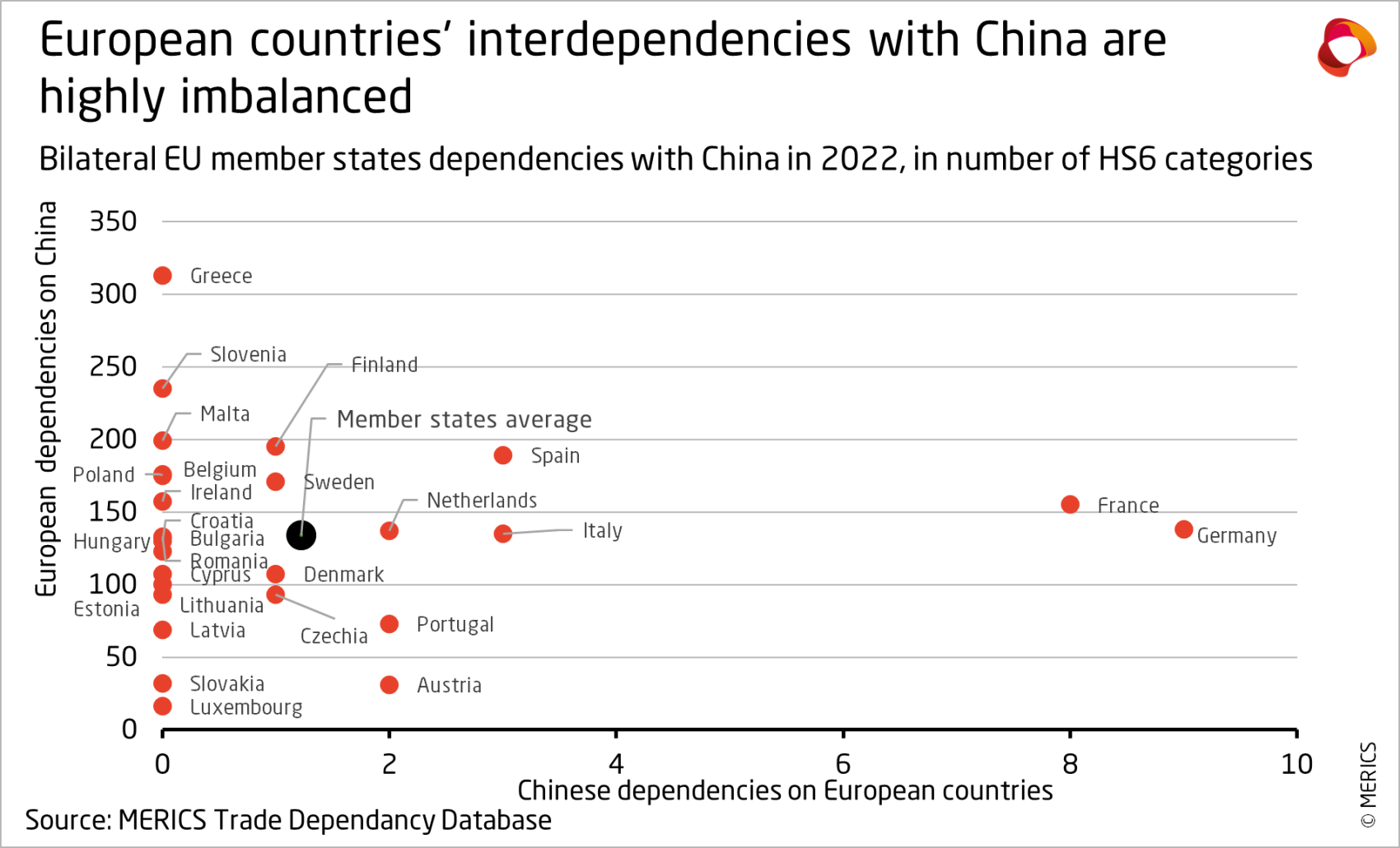

This is crucial as the MERICS database also shows that no member state can exert the kind of trade pressure on China that comes close to the pressure China can apply on each EU country. While China is dependent on between one and nine products from individual EU countries, they are typically dependent on 134 products imported from China (see exhibit 1). On average, China has more than a hundred times the trade leverage on an EU country than the other way around.

For each product category in which China reported a significant trade deficit, recorded at least 30 percent of imports as coming from the EU and had few alternative suppliers in other countries, the “average” EU member state had over a hundred products for whose supply it was similarly dependent on China (for more details on the MERICS Trade Dependency Database see here). While the statistics – based on more than 5,600 “HS6” product categories used by customs authorities – reveal nothing about the strategic importance of these products, they throw a stark light on the imbalance of EU-China trade relations.

EU trade policy makes China a more important trading partner

A centralized trade policy gives the EU more clout by mathematically making China a more important trade partner than it is for individual countries. While aggregating member states' trade with China in 2022 increased Europe's dependence on China to 421 products from an average of 134 at the country level, it raised China's dependence on EU products much more, to 120 categories from an average of 1.2. While China has more than 100 times the trade leverage over an average EU country, it has “only” 3.5 times the trade leverage over the EU.

As a proxy for trade power, import dependency data has its limitations. Even the granular HS6 international customs codes can aggregate goods in a way that obscures some vital product or critical technology. For example, semiconductor lithography equipment made by the Dutch company ASML’s does not register in China’s dependency statistics, even though it is central to China’s ambitions to manufacture advanced chips. Customs records lump ASML’s high-precision machinery together with less advanced products, hiding China’s dependence.

Data on dependencies also ignore how critical whole product categories can be. As China’s exports still include many basic consumer products, the geopolitical weakness implied by the imbalances outlined above is certainly less daunting than the numbers suggest. But this is a dimension that is difficult to capture objectively and systematically. Moreover, the differences in trade power are large enough to still make interdependence a matter of the utmost urgency.

China’s dependencies have decreased over the last two decades

Over the last two decades, China has almost halved the number of European-made products on which it relies, a pattern that has been seen across EU member states. Given China’s industry-focused development, Germany has suffered most. China’s dependencies on Germany fell to nine products in 2022 from 24 categories in 2001. France has fared better in comparison as China’s dependencies have remained broadly stable at eight, but this figure gives a somewhat distorted picture as it includes a shift towards luxury textiles of low strategic value.

China has shown a willingness to weaponize interdependencies. Trade imbalances with it therefore carry risks for Europe. China’s approach was on display in late 2021, when it banned imports from Lithuania in retaliation for Taiwan opening a representative office in Vilnius. Another example is China’s unofficial, de facto ban on the export of some key graphite products to Sweden, which began in 2020. Such retaliation is not new, but the incidents have highlighted Beijing's willingness to use economic vulnerabilities as an extension of diplomacy.

The EU therefore needs a collective response to protect its economic security and strategic autonomy. Some steps have already been taken. Firstly, member states have collectively acknowledged the problems of the EU’s growing dependence on trade with on China. The European Commission has carried out a comprehensive assessment of dependencies, including sectoral ones, with some results being made public and some internal.

EU needs to redouble efforts to address its reliance in China

Efforts are underway to address some dependencies, notably in critical raw materials, telecommunications, green industries and semiconductors – some EU funding auctions in areas like batteries now include clauses to foster diversification from China and Brussels has proposed a similar rule for public procurement in green and strategic sectors. An EU Anti-Coercion Instrument has been established to retaliate against any weaponization of dependencies.

Other steps, such as anti-dumping measures on biodiesel and the anti-subsidy investigation against Chinese-made electric vehicles (EV), are also meant to prevent existing dependencies from growing. The EU has appealed to the WTO against China’s investigation into European diary subsidies, which Brussels views as unfair retaliation for its EV measures.

The EV case has shown that China will not sit idly by. Beijing is focused on its techno-industrial ambitions and shows little interest in addressing any negative spillovers. Europe’s resolve is sure to be further tested as EU resilience efforts take effect and trigger a Chinese reaction to any impact on its economic interests. Public wavering – such as Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez questioning EU tariffs on Chinese EVs during visit to China – puts European unity in question, undermines Europe’s international credibility and the blocks long-term interests.

The EU needs to increase domestic production capacity and diversify European imports. Mandatory stockpiling of essential goods may need to be extended beyond medical products. Such efforts are costly and should in consequence be targeted only at critical sectors – and not all of them need to be decided at the EU level if coordination and information sharing can avoid duplication at national level in a time of budgetary constraints. A technical working group within the structures of the European Council could facilitate and incentivize such cooperation.

Mitigation will depend on the EU activating European instruments when forced to do so. With a toolbox of resilience measures at its disposal, the EU’s credibility depends on its willingness to use them. Brussels needs to align member states’ views, build trust and lower the coordination costs of potential deployment, for which regular high-level Council discussions would help prepare the ground. Member states should view the scales of trade imbalances, as reflected in specific import dependencies, with urgency – and they cannot let the issue slip down the priority list once the biggest tensions over critical supplies have been addressed.

This "MERICS Comment" was made possible with support from the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.