Xi needs to embrace the EU’s emissions levy on imports

China should recognize the CBAM as a fair and crucial tool, says François Chimits. Global cooperation must prevail over geopolitical maneuvering in the fight against climate change.

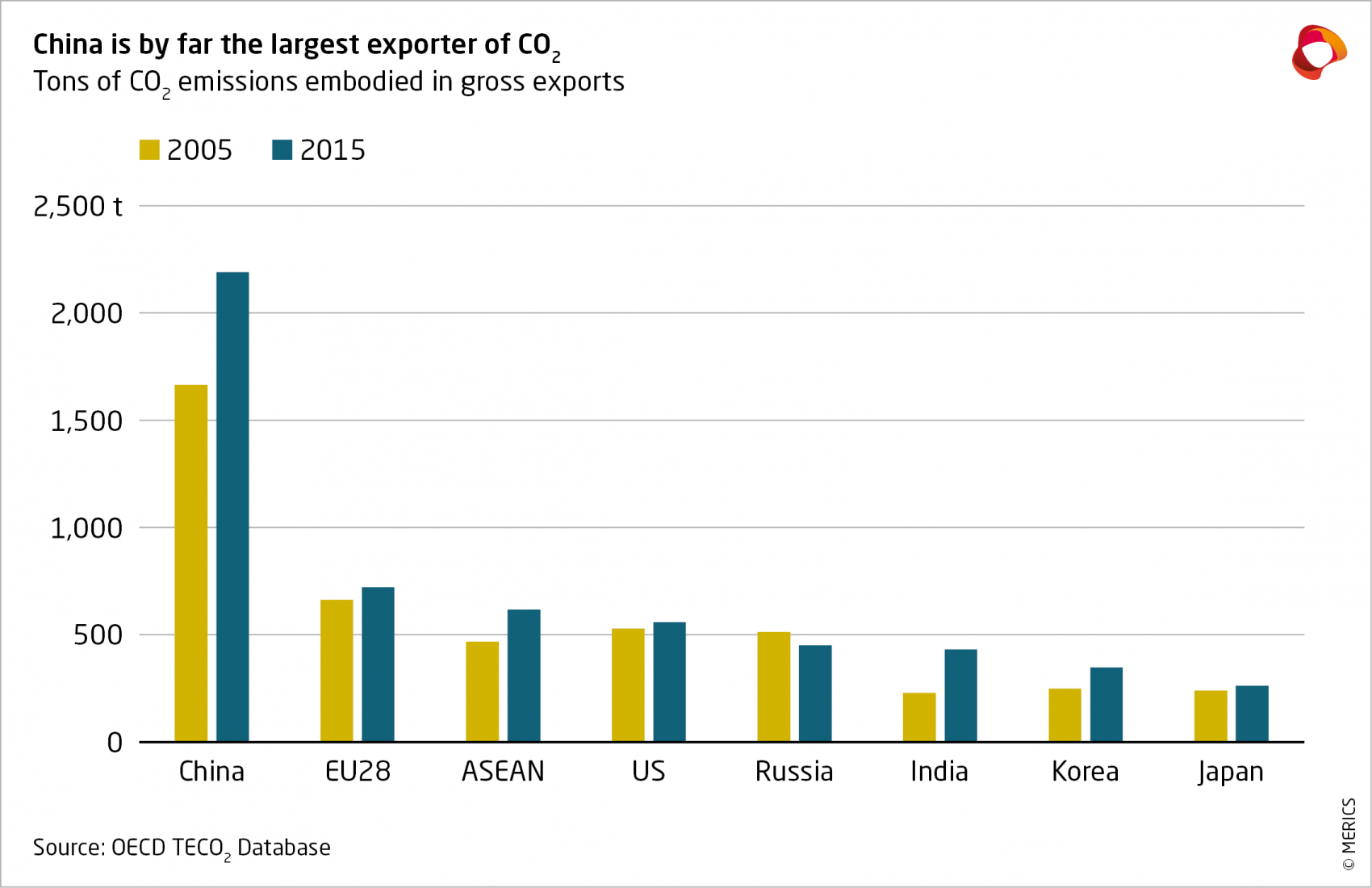

As the largest “exporter” of CO2, China officially opposes EU plans for a levy on carbon-intensive imports as opportunistic protectionism. Xi Jinping was referring to the carbon border-adjustment mechanism (CBAM) when he recently warned French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel about using climate concerns as an “excuse for trade barriers”.

But rather than putting himself at the head of a developing-country movement decrying “green” trade barriers, China’s president should heed the domestic voices calling for a more constructive approach to the European initiative.

Xi does in theory have a point. A carbon border-adjustment levy is a trade restriction that can serve protectionist purposes. It is meant to limit so-called carbon leakage by adjusting import prices to compensate for lower production costs in countries with more permissive climate policies. This increases the climate efficiency of domestic efforts, raises their political acceptance at home and lowers the risks of climate free riders.1 But any levy exceeding the cost domestic producers pay for observing emission constraints narrows such a scheme’s overall climate benefit and privileges home-made products in a clearly protectionist way.

In practice, however, the CBAM proposed by the European Commission intends to be fair, transparent and inclusive. The July proposal lays out the EU’s aim to reduce carbon leakage from the EU carbon market (with its high carbon prices and attendant emissions-trading scheme (ETS)) in an effort to be compatible with the World Trade Organization’s rules against discriminating against products made abroad. Like EU-made goods, foreign-made products would be charged the EU ETS price for carbon emitted – minus any carbon price already levied in the country of production and any emissions exemptions EU production benefits from. Also, during a three-year “blank run phase,” levies would be calculated but not charged, giving the EU and its partners until 2026 to tweak the system as problems arise.

CBAM’s impact on China looks set to be limited

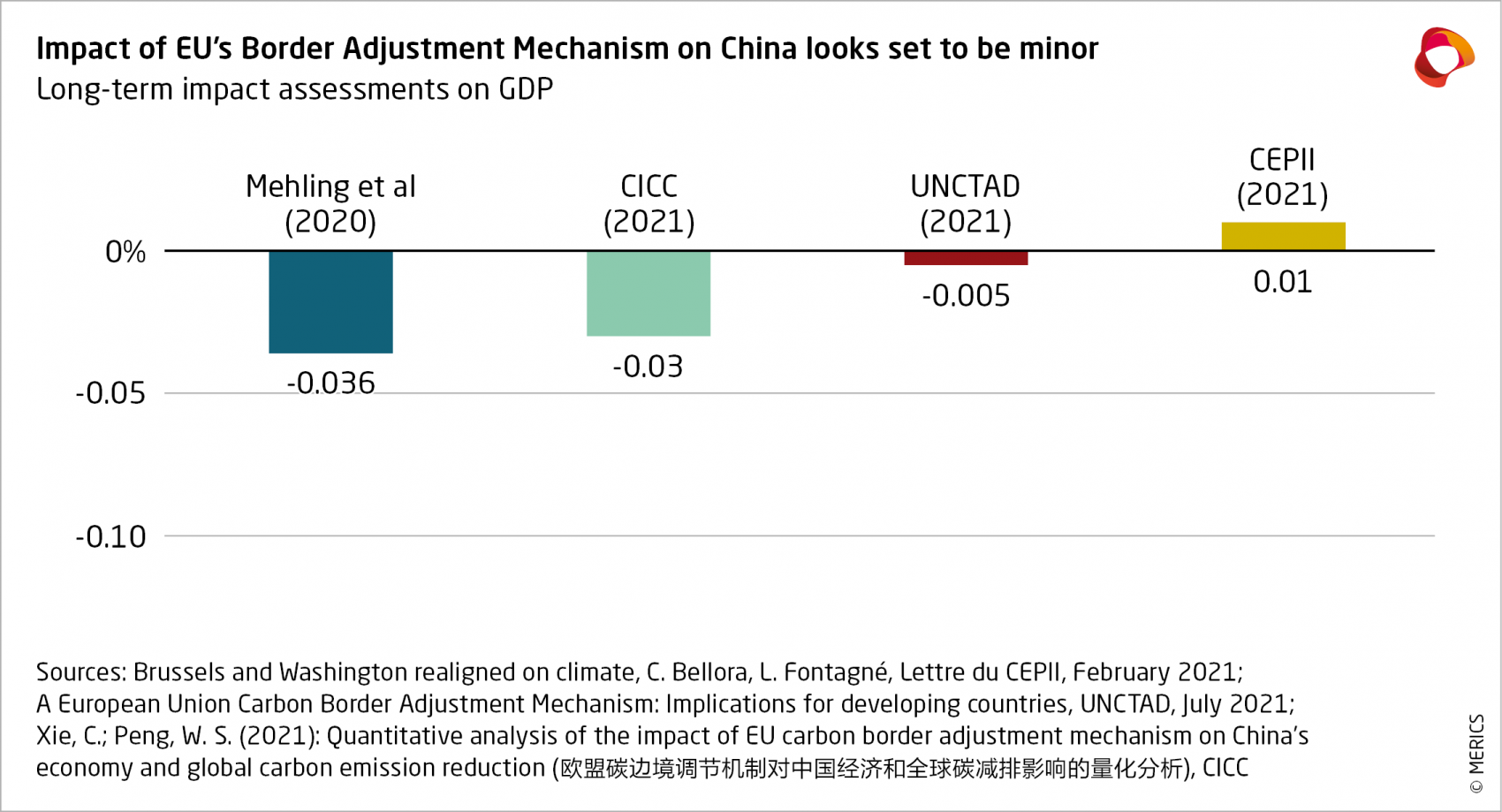

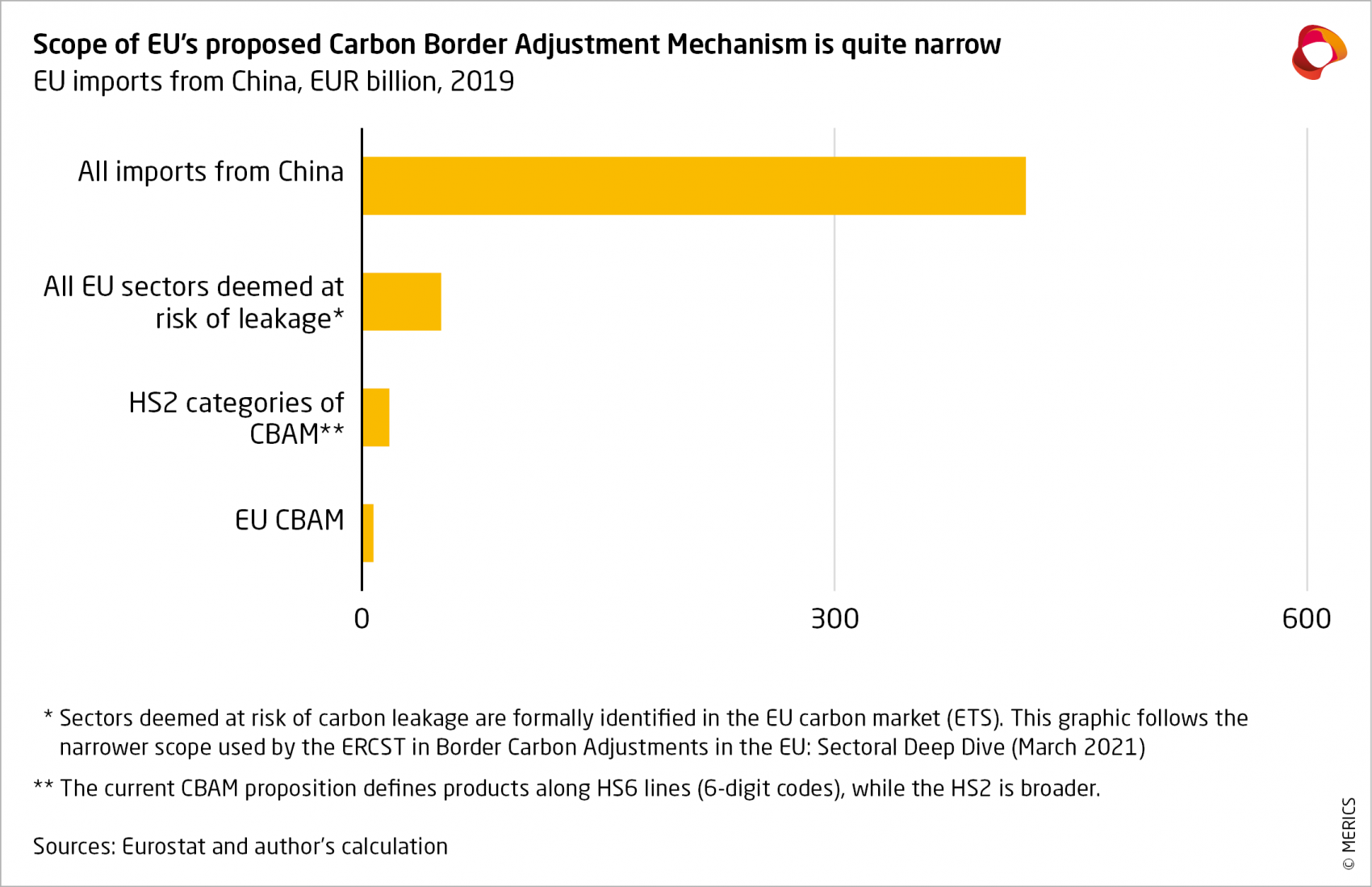

Contrary to Xi’s fears the proposal’s impact on China looks set to be limited. At first, the EU levy would be limited to products with a high risk of carbon leaking outside the EU ¬– cement, steel, aluminum, chemicals and electricity. On top of that, the EU’s measure of each product’s “embedded emissions” would include only direct emissions during production, not those generated by inputs or electricity supplied to the production site. Three recent studies expect only a small long-term impact on China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – and one even forecasts a slight boost due to higher EU production costs.2

Arguments like these seem to be driving a growing sense in Chinese policy circles that demonizing the CBAM might ultimately be counterproductive and the initiative worthy of another look. Zhou Xioachuan, the retired long-serving governor of China’s central bank, in June emphasized the necessity for worldwide cooperation on carbon pricing, the usefulness of CBAM in that respect – and the likely need for China to implement a similar mechanism in due course. He advised policymakers to scrutinize the details of the EU CBAM to assess whether it was indeed “green protectionism” or actually a way of reducing CO2 emissions.

This summer, a study by Germany’s Adelphi public-policy consultancy and China’s Tsinghua University concluded: “If the EU CBAM is fairly designed and carbon costs in other countries are reasonably credited, expansion of China’s national ETS to cover CBAM-related sectors could be one of China’s best policy instruments for responding to the mechanism”. And the former chief economist of China’s central bank, Xu Zhong, implicitly accepted the CBAM by arguing in an opinion piece that “proceeds from such mechanisms proposed by developed countries must be used to help reduce carbon emissions in developing countries.”

China could benefit from constructive engagement on the EU carbon trading scheme

China has good reasons to cooperate on the EU CBAM, not least because its commitment to reach its carbon emissions peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 imply tremendous efforts. One effect is likely to be impactful emissions pricing on China’s nascent carbon market – which, as Zhou pointed out, would soon lead to EU-style carbon leakage issues and CBAM as the most efficient cure.3 By constructively engaging with the EU now, China would be able to influence the scheme by raising concerns about allocating revenues, dealing with a lack of producer emission information, and looking out for the poorest countries.

Continued opposition to a non-discriminatory CBAM would solidify China’s perceived role as the narrow advocate for developing countries opposed to the scheme.4 This would hamper much-needed international co-operation on climate policy – the standoff between developed and developing economies has been one of the main roadblocks to cooperative global outcomes in trade as well as environmental policy over the past decades. Rather than exploiting this impasse for geopolitical and internal gains, China should work with the EU to pave the way for a crucial green tool that would also greatly help its decarbonization efforts.

References:

OECD (2020), Climate Policy Leadership in an Interconnected World: What Role for Border Carbon Adjustments?, OECD Publishing, Paris

Kuusi, T., Björklund, M., Kaitila, V., Kokko, K., Lehmus, M., Mehling, M. & Wang, M. (2020), Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and Their Economic Impact on Finland and the EU, Publication of the Finnish Government's analysis, assessment and research activities

- Endnotes

-

[1] A carbon leakage is when “foreign emissions increase because of the introduction of domestic climate policies” (OECD 2020). Carbon leakages directly affect the efficiency of national climate efforts, as well as indirectly by denting the political support for such climate policy at home. Here, as for the CBAM discussion, we are only referring to direct carbon leakages, which is when this increase materializes through a direct shift of production of a certain good, and not through lower prices of carbon intensive energy sources (called indirect emissions). The reality of carbon the leakage phenomenon has long been empirically challenging to identify, mostly because of the lack of stringent efforts to curb emissions. This piece doesn’t discuss that very interesting point, for which readers can address OECD (2020).

[2] Brussels and Washington realigned on climate, C. Bellora, L. Fontagné, Lettre du CEPII, February 2021.

[3] See Chapter 3 of World Economic Outlook, October 2020: A Long and Difficult Ascent (IMF October 2020) as well as Kuusi and al. (2020) and EU Climate Mitigation Policy (IMF European Department, September 2020).

[4] One such instance was at the November 2020 Market Access Committee of the WTO, where several developing countries took the floor to criticize the EU project, including India, Russia and South Africa.