EV battery investments cushion drop to decade low: Chinese FDI in Europe 2022 Update

Report by Rhodium Group and MERICS

Key findings

- China’s global outbound investment falls to an 8-year low: In line with the global decline in cross-border investment, Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) fell by 23 percent in 2022 compared to 2021, to USD 117 billion (EUR 111 billion). China’s outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity also dropped, falling 21 percent from 2021 levels to a total of EUR 22 billion. A range of external and internal factors – from China’s zero-Covid policies to rising global risks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – created strong headwinds for Chinese investors.

- Chinese investment in Europe (EU-27+UK) continues its multi-year decline: Chinese FDI in Europe reached a decade low of just EUR 7.9 billion in 2022, down 22 percent compared to 2021. The drop takes Chinese investment back to its 2013 level. A lack of Chinese M&A activity was the prime reason for the fall. Only one transaction – Tencent’s purchase of British video game developer Sumo Digital – exceeded one billion euros.

- Greenfield investment overtakes M&A for the first time since 2008: Driven by electric vehicle battery factories, Chinese greenfield investment in Europe increased by 53 percent, exceeding M&A flows for the first time since 2008.

- Investment concentrates heavily on the “Big Three” and Hungary: 88 percent of investment flowed to just four countries, the “Big Three” European economies (the UK, France and Germany) and Hungary. All four received major greenfield investments by Chinese battery makers, as well as most of the year’s M&A activity.

- Consumer products and automotive remain the top sectors: As in 2021, consumer products – again driven by a single large acquisition – and automotive remained the two top sectors. Three quarters of total Chinese investment flowed into these two sectors.

- Europe has become a key part of China’s global electric vehicle expansion: Battery investments are now the mainstay of Chinese investment in Europe. Further greenfield expansion in Europe in up- and down-stream segments of electric vehicle (EV) value chains, including vehicle production, are being considered by Chinese firms.

- European governments increase scrutiny of Chinese investment: They continue to tighten investment screening measures, impacting Chinese acquisitions of strategic assets such as European semiconductor companies and critical infrastructure.

- A strong rebound in 2023 is unlikely, but investment could recover slightly: The end of China's zero-Covid policy could boost Chinese outbound investment in 2023, but China's fragile economic situation and geopolitical pressures make a rebound to mid-2010 investment levels unlikely.

1. Introduction: A new era of Chinese FDI

Global cross-border investment activities declined in 2022 after the strong recovery of foreign direct investment flows (FDI) seen in 2021. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global direct investment flows dipped after the first quarter of 2022 due to the global crises triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war escalated inflation as food and energy costs soared, leading central banks to hike interest rate in advanced economies. The resulting economic uncertainty and shifts in global financial conditions have spread caution and suppressed investment.

Chinese global investment was no exception to the trend, falling again in 2022. According to official Chinese statistics, China’s outbound non-financial investment fell by 23 percent compared to 2021: it reached its lowest value since 2014, registering a total of USD 117 billion (EUR 111 billion) in 2022. China’s global outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity also slipped to a record low. According to Bloomberg data, completed Chinese M&A totaled just EUR 23 billion, down 21 percent on the 2021 record low of EUR 38 billion.

Next to global factors hindering investment activities, domestic and China-specific factors also limited Chinese global outward FDI. These included ongoing domestic constraints on outbound capital flows, economic uncertainty caused by the tech rectification campaign and China’s adherence to a zero-Covid strategy for most of 2022. The latter complicated cross-border travel and thus deal-making activities. In Q2, the total shutdown of Shanghai, China’s financial center, likely compounded the trend. Chinese investors who overcame these obstacles to pursue deals found themselves facing stricter investment screening regimes and political opposition in many places.

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 1

In this new iteration of the MERICS-Rhodium joint report on Chinese FDI in Europe, we consider trends over the last decade to explain China’s changing investment footprint in the region. We also look at Europe’s role in China’s global FDI in electric vehicles (EVs). Finally, we outline how Europe’s stricter scrutiny of investment could impact Chinese investment.

2. Chinese investment in Europe has seen profound changes over the last decade

In 2022, Chinese FDI in Europe reached a fresh decade low of EUR 7.9 billion, down 22 percent on the previous year. The drop reflected the 23 percent decline in China’s global investment activities. The most recent decline means that Chinese FDI in Europe is now 83 percent below its 2016 peak. Back then, Chinese capital controls were much looser, China’s economic and regulatory conditions were more favorable, and scrutiny of Chinese investment in Europe was much more limited.

Given the new environment of low investment flows from China to Europe, a handful of deals can cause large sectoral or geographical shifts, complicating any analysis of key aggregate patterns. Still, we have highlighted several key developments of the past few years below, as well as how China’s FDI into Europe now differs drastically from a decade ago.

2.1. Greenfield now dominates China's FDI to Europe

After years of rapid growth, levels of Chinese greenfield investment in Europe have overtaken M&A transactions for the first time in 20 years, reaching EUR 4.5 billion (and 57 percent of the total). This reversal was propelled by strong expansion in greenfield investment coupled with a massive downturn in M&A activity from its peak in 2016.

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 2

The increase in greenfield investment was driven mainly by a few large-scale projects, almost exclusively concentrated in the automotive sector as Chinese battery giants – including CATL, Envision AESC and SVOLT – invested in building battery plants in Germany, Hungary, the UK and France (for more see chapter 3).

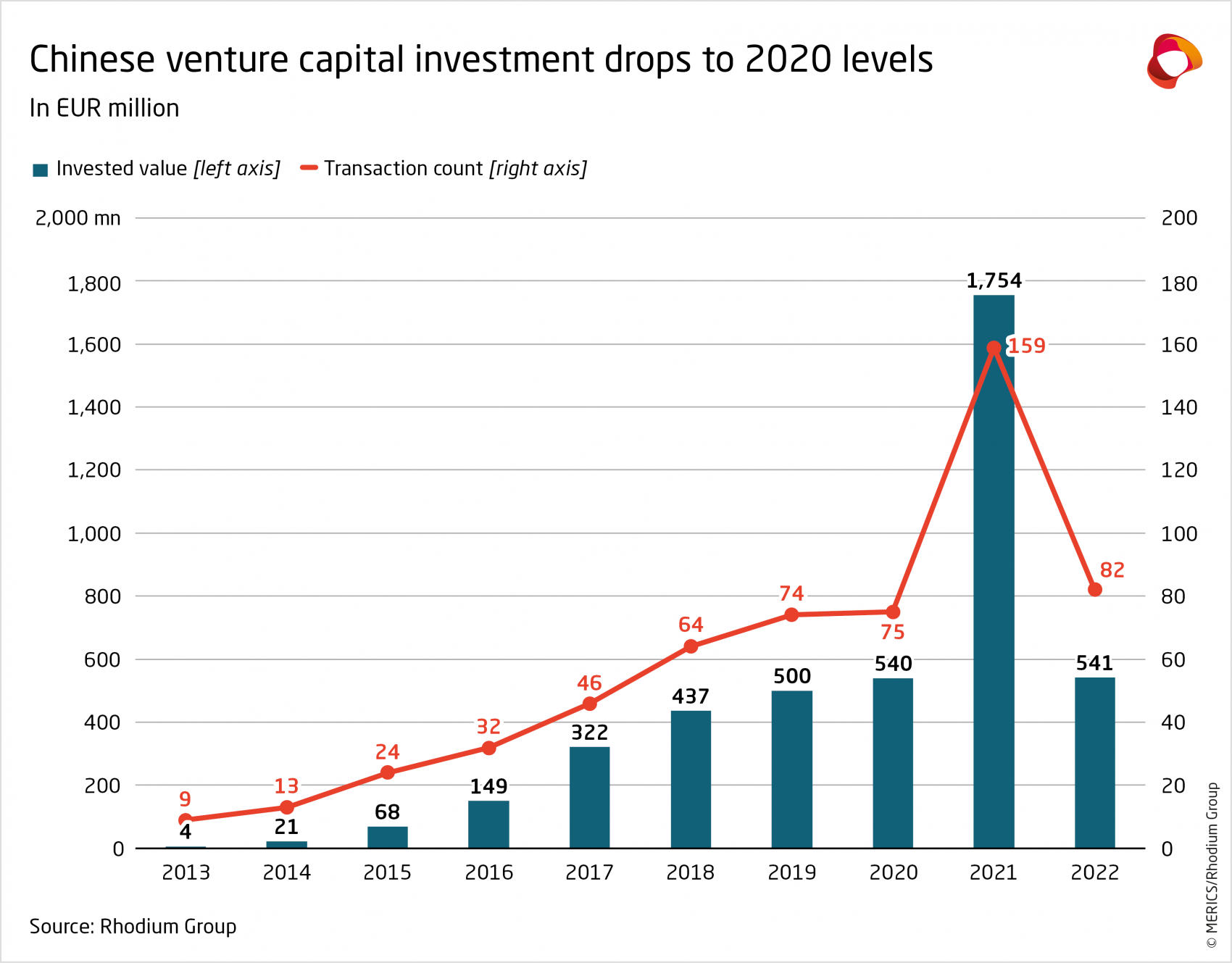

By contrast, Chinese M&A activities in Europe fell to their lowest level since 2011, with just EUR 3.4 billion invested. The continued absence of large transactions was the main reason for this – there was only one billion-Euro acquisition, namely Tencent’s purchase of British video game developer Sumo Digital. While the scale and value of M&A transactions has been gradually decreasing since 2016, the number of individual transactions had remained steady (see exhibit 4) till last year. Acquisitions have generally become smaller. In 2022, we also saw a sharp downturn in individual M&A deals in Europe.

Exhibit 3

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 4

2.2 Chinese investment continues to concentrate on "big three", with greater variations at the margins

In 2022, this was the case as well. As in previous years, Chinese investment in Europe was highly concentrated, with 88 percent of total FDI flowing to only four countries (see annex for overall geographical distribution). The “Big Three” economies of Germany, France and the UK accounted for 68 percent of China’s FDI in the region – even higher than the 56 percent average these three countries received in the preceding decade (see exhibit 5).

Among them, the UK received the most Chinese investment (EUR 2.3 billion), mainly driven by Tencent’s Sumo Digital acquisition for EUR 1.3 billion and Envision AESC’s continued greenfield investments in a battery plant in Sunderland. Germany and France attracted EUR 1.9 billion and EUR 1.3 billion respectively. Investments were driven by greenfield battery plant investments, Wallaby Medical’s EUR 539 million takeover of German medical equipment maker phenox GmbH and Tencent’s acquisition of shares in French company Ubisoft for EUR 300 million.

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 5

High levels of Chinese investment in Hungary (EUR 1.6 billion) were more out of the ordinary, accounting for 20 percent of total investment. Between 2017 and 2021, the country received less than 1 percent of all Chinese investment in Europe. In 2022, by contrast, Chinese investment in Hungary was almost entirely driven by CATL’s new gigafactory with an announced total value of EUR 7.6 billion EUR (due to tracking greenfield operations over the time of construction rather than all at once, we have so far ascribed EUR 1.5 billion).

Another Chinese battery producer, EVE, reportedly also plans to set up a battery plant near Debrecen, Hungary, to supply European carmakers, and SEMCORP a producer of lithium-ion battery separators has already started local production. Leveraging this wave of Chinese investment, Hungary could develop into a battery manufacturing hub for Europe. Hungary has relatively strong political ties with Beijing and several carmakers have built assembly plants there, including Mercedes-Benz and Audi. Outside of Hungary there was no new Chinese investment in Eastern Europe.

Investment in Southern Europe (EUR 656 million) decreased by 38 percent and was highly concentrated on Spain due to two investments in renewable energy assets by China Three Gorges for EUR 560 million, a state-owned enterprise (SOE) that already possesses other renewable energy assets in the country. Investment in Northern Europe collapsed to EUR 200 million, due to a dearth of new M&A deals and greenfield projects. Almost the entire sum was due to continued investment by TikTok’s parent company Bytedance into a data center in Ireland.

![]() Hover over/tap the map to see more details.

Hover over/tap the map to see more details.

Exhibit 6

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 7

2.3 Automotive investment has become the core driver of Chinese investment in Europe

Although Chinese investment has remained relatively stable in its geographical spread, there have been big changes in its sectoral distribution. There has been a sharp downturn in energy, infrastructure, real estate and finance – the sectors that dominated Chinese investment in Europe until 2017 (see exhibit 8). This stems from a greater focus on reducing financial risks from highly indebted companies in these sectors in China, stricter capital controls, and now tighter investment screening measures in Europe, particularly in critical infrastructure because of deteriorating EU-China relations and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The fall in Chinese investment in these SOE dominated sectors is also linked with the fall in Chinese SOE investment in Europe (see annex). Chinese capital now flows towards sectors where Chinese private firms are highly competitive, like automotive, or end consumer- oriented sectors like video gaming or household products.

Greenfield investments in the Big Three economies and Hungary by Chinese automakers have produced a high concentration on the automotive sector amid low overall Chinese investment. With 53 percent of total Chinese investment, automotive received the highest concentration of Chinese investment in a single sector in over a decade (see annex for the sectoral distribution). Previously, Chinese investment in automotive was primarily focused on acquisitions of firms like Volvo in Sweden by Geely in 2010. Now, Europe has become a key region in China’s global electric vehicle (EV) expansion (see chapter 3), which shows both China’s strength in the EV supply chain and growing need to be close to the market to gain a foothold in Europe’s auto industry.

In contrast to the greenfield nature of China’s European automotive investments, the investment in end-consumer-oriented sectors was driven by large acquisitions. Following the huge Hillhouse Capital acquisition of Philip’s household appliances businesses in 2021 (EUR 3.7 billion), Tencent acquired British video game maker Sumo Digital for EUR 1.3 billion. Large Chinese acquisitions are increasingly limited to these consumer-focused sectors because they are generally considered non-sensitive.

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 8

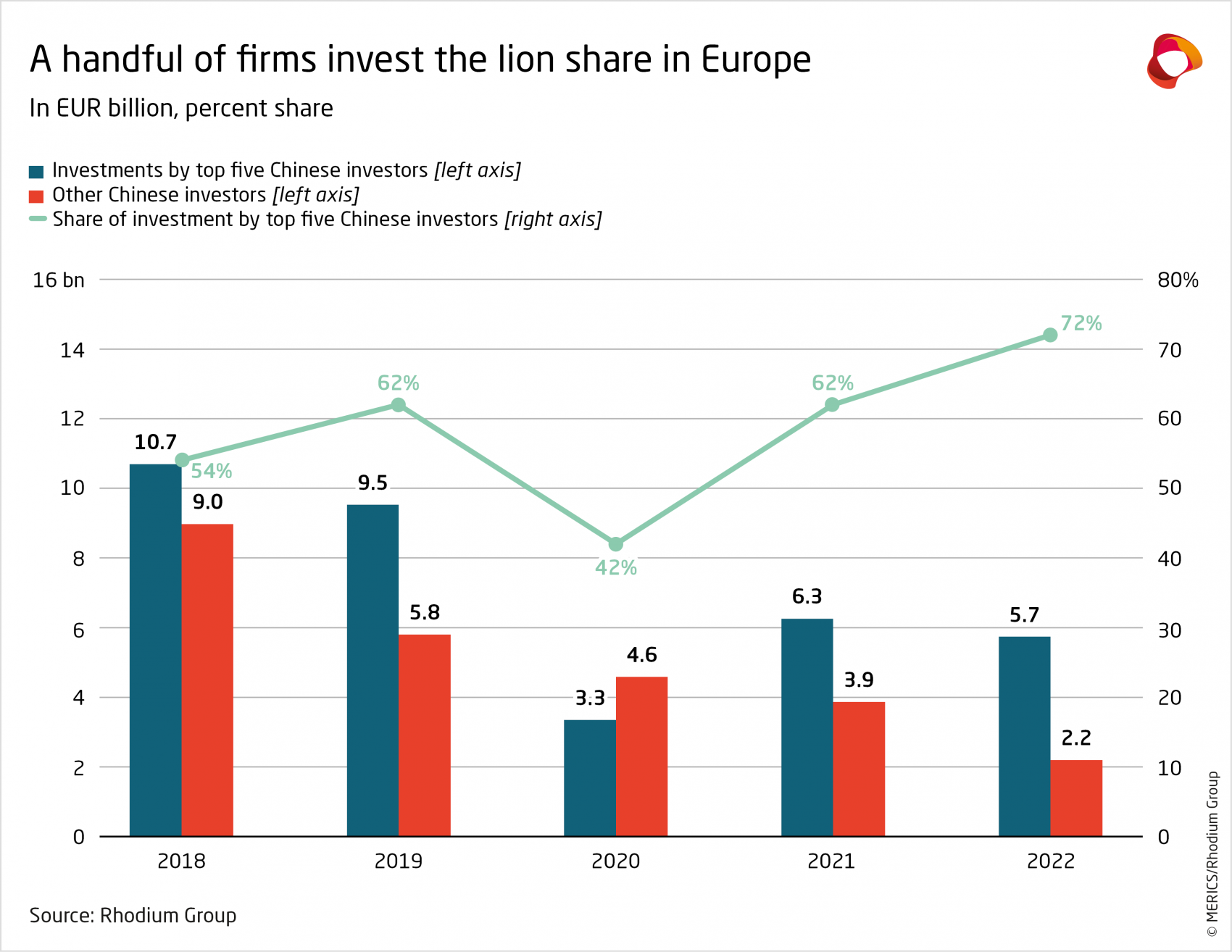

2.4 Chinese investment is increasingly concentrated on a handful of Chinese firms

Chinese investment in Europe has always come mainly from large investors, but this pattern of concentration has intensified. In 2022, a whopping 72 percent of total investment stemmed ultimately from just five investors, including CATL and Tencent, a rise of 18 percentage points on five years earlier. The type of investor and channel of investment has also changed. A decade ago, investors were primarily major SOEs acquiring European firms. Now, they are private firms building greenfield assets in Europe.

3. In focus: Europe’s role in China’s global EV expansion

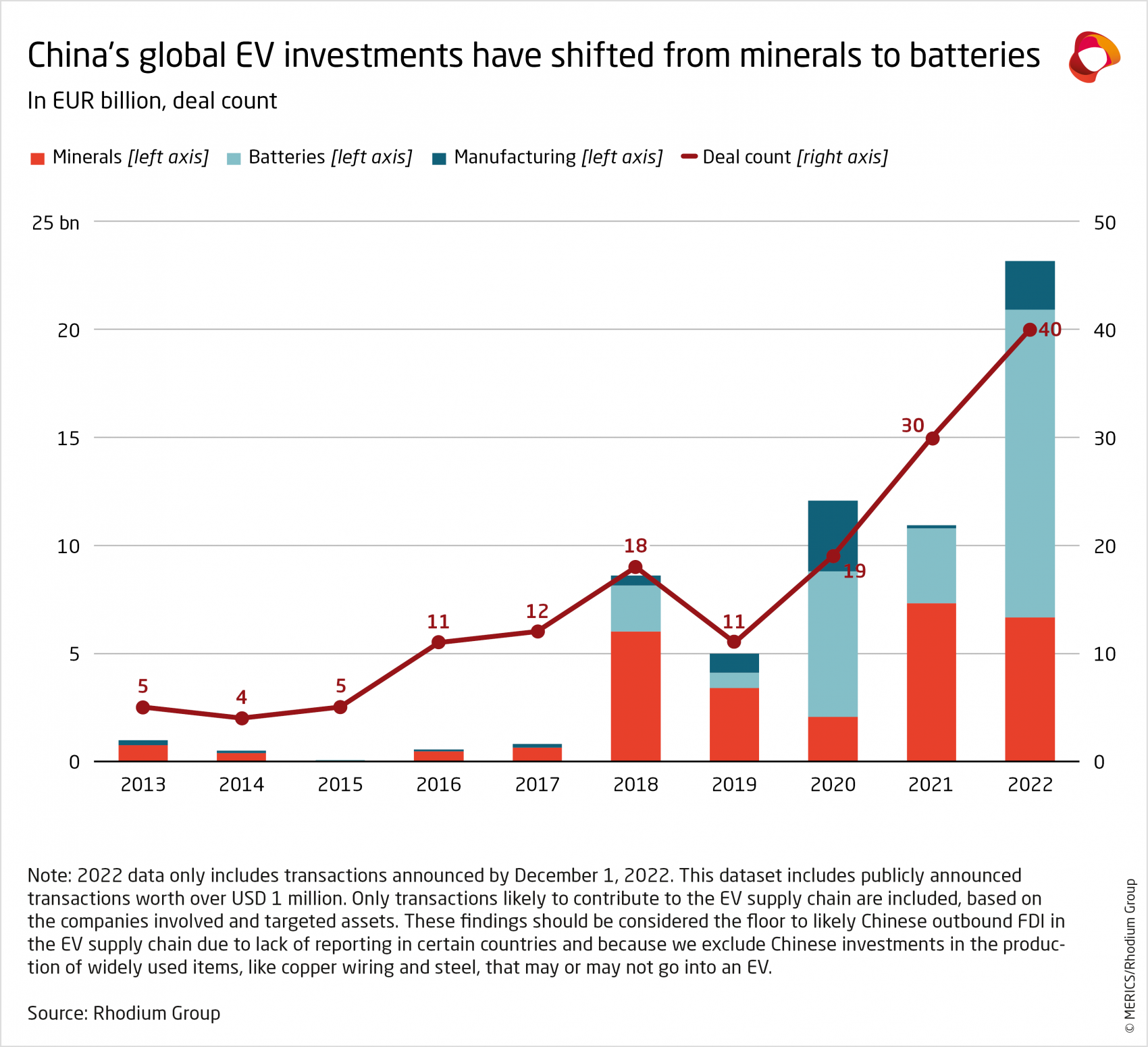

Chinese battery plant investments have become a key driver of overall Chinese FDI in Europe. The greenfield deals are part of China’s global push to capture key inputs and global market shares for its already vibrant and domestically leading EV sector.

From 2016 to 2022, announced Chinese FDI in the EV value chain surged more than forty- fold from USD 605 million in 2016 to over USD 24 billion in 2022 (see exhibit 10). EV sector deals have accounted for 19 percent of announced Chinese global outbound FDI over the past five years and represented 58 percent of China’s total outbound FDI in 2022 alone.

China’s EV expansion efforts have evolved from an earlier focus on minerals deals in countries such as the Congo, Indonesia and Chile (still a major investment driver) to a growing number of companies now setting up battery manufacturing plants close to key final demand markets.

China’s interest in Europe, the world’s second biggest EV market after China, is therefore not surprising. It has comparatively good charging infrastructure and generous government purchasing subsidies, developed within a wider green agenda to decarbonize road transportation. Furthermore, unlike other major automotive hubs such as Japan or South Korea, Europe has few major battery firms of its own and is still very open to Chinese investment in the industry.

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Exhibit 11

That creates significant expansion opportunities for globally leading Chinese battery players like CATL or SVOLT. Since 2018, Chinese battery firms have announced investments worth USD 17.5 billion in Europe. The anticipated output by their European factories could be roughly 20 percent of the continent’s total battery production capacity by 2030.

![]() Hover over/tap the map to see more details.

Hover over/tap the map to see more details.

Exhibit 12

So far, the largest of these investments have focused on the production of battery modules and packs, such as CATL’s 100 GWh plant in Hungary, which will be Europe’s biggest when completed. But Chinese firms are also eyeing opportunities further up- and downstream.

Upstream, Chinese investors are moving into battery inputs. In 2022, CNGR Advanced Material and Finnish Minerals Group announced plans to establish a 60:40 joint venture to build a plant for precursor cathode active materials, which are used to make lithium- ion batteries. Semcorp’s Hungarian EUR 184 million plant will produce lithium-ion battery separator films. In Germany, Wuxi Lead Intelligent Equipment acquired bankrupt specialized machinery company Ontec Automation a few months after winning a major contract to supply Volkswagen’s new Salzgitter battery plant with equipment.

Batteries could lay the foundations for a broader downstream trend too. In 2022, China exported 371,000 EVs, worth EUR 8.3 billion, to the EU-27, a rise of 360 percent compared to 2020. Currently, this export push is dominated by imports from Tesla’s production site in Shanghai. However, if the push proves successful for Chinese EV makers, they could start producing in Europe. Some are already considering opportunities: Volvo (owned by Geely) announced its first new European manufacturing site for almost 60 years, in Slovakia. The plant will build only EVs. BYD – China’s biggest EV-maker and second-biggest battery producer – is also scouting for a European manufacturing site.

Producing in Europe, rather than exporting to it, would help Chinese EV makers save on tariffs and transport costs, and – importantly – address the increasing risks of political pushback. In October 2022, Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares called on the EU to increase tariffs on made-in-China vehicles. His comments echo the resistance to Japanese carmakers when they entered the European market in the 1980s. Japanese, and later Korean, carmakers invested in local production to avoid tariffs, but also to appease political concerns in Europe. Taken together, these factors suggest Europe could receive yet more Chinese EV investment in the years ahead.

The European picture contrasts sharply with the US push for “China-free” battery supply chains. The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) ties EV tax credits to batteries that are free from minerals or components from entities of concern (which includes China). The IRA has given pause to Chinese firms planning investment in North America. CATL slowed plans to open new battery plants after scouting sites in South Carolina and Kentucky as well as Mexico.

Some firms are also turning to creative solutions: to continue working with Chinese battery companies, who are the current global market leaders and centralize much of the industry know-how, Ford announced plans to build a US-based battery plant that would license technology from CATL, in the hope it can still access US EV tax credits.

The incentives offered by the IRA coupled with energy cost spikes in Europe have led some companies, including Tesla and Northvolt, to delay energy-intensive battery projects on the continent and focus on the United States instead. According to Bloomberg NEF data, Europe’s global share of investment in lithium-ion batteries dropped from 41 percent in 2021 to just two percent in 2022. Chinese firms might be more inclined to complete projects in Europe as they have fewer options to expand in the United States. Tying Chinese battery makers and Europe more closely together.

4. In focus: Europe heightens scrutiny of Chinese investment

4.1 European investment screening regimes limit Chinese acquisitions of strategic technologies

Even though most of the decline in Chinese investment in Europe has to do with domestic factors, member states’ implementation of the EU’s investment screening regulation also contributed to the trend, especially in sensitive sectors. European countries continued to strengthen their investment review mechanisms last year. In 2017, regulations to screen foreign investments existed in only 11 EU member states, whereas by late 2022 all except two (Bulgaria and Cyprus) had mechanisms in place or were in the process of establishing one.

2022 witnessed an uptick in publicly disclosed reviews of Chinese investments jumping from 11 to 16 on our count. There are several possible explanations for this increase:

- Expanded regulations could have led to more screening

- Greater interest by Chinese investors in strategic sectors, given barriers to similar transactions in the US or Japan

- European governments might have become more transparent about the reviews. In the past most screening of transactions were kept confidential

Most of the publicly known cases of reviewed Chinese investments seemed to focus on critical infrastructure and strategic dual-use technologies (see exhibit 13). One third of screenings involved planned acquisitions of semiconductor firms – a sector that both the Chinese and European governments regard as highly strategic. With the recent US export controls on semiconductor equipment, China will be even more inclined to invest in European technology providers—when and if it can. Noteworthy, European screeners have also been reviewing investment by Chinese-owned European firms like Syngenta.

The UK government – which is usually more transparent about its investment screening measures than peer European governments – has reviewed at least three investments in the semiconductor sector (see exhibit 13). Notably, it ordered Chinese-owned Nexperia to sell at least 86 percent of its shares in the Newport Wafer Fab a year after the deal went ahead. The UK government saw national security risks arising from the semiconductor technology and know-how, as well as the location of the site, which “could facilitate access to technological expertise and know-how in the South Wales Cluster”. It found that the deal could “prevent the cluster being engaged in future projects relevant to national security”. This comprehensive definition of national security related to clusters could be a further barrier to future Chinese investments.

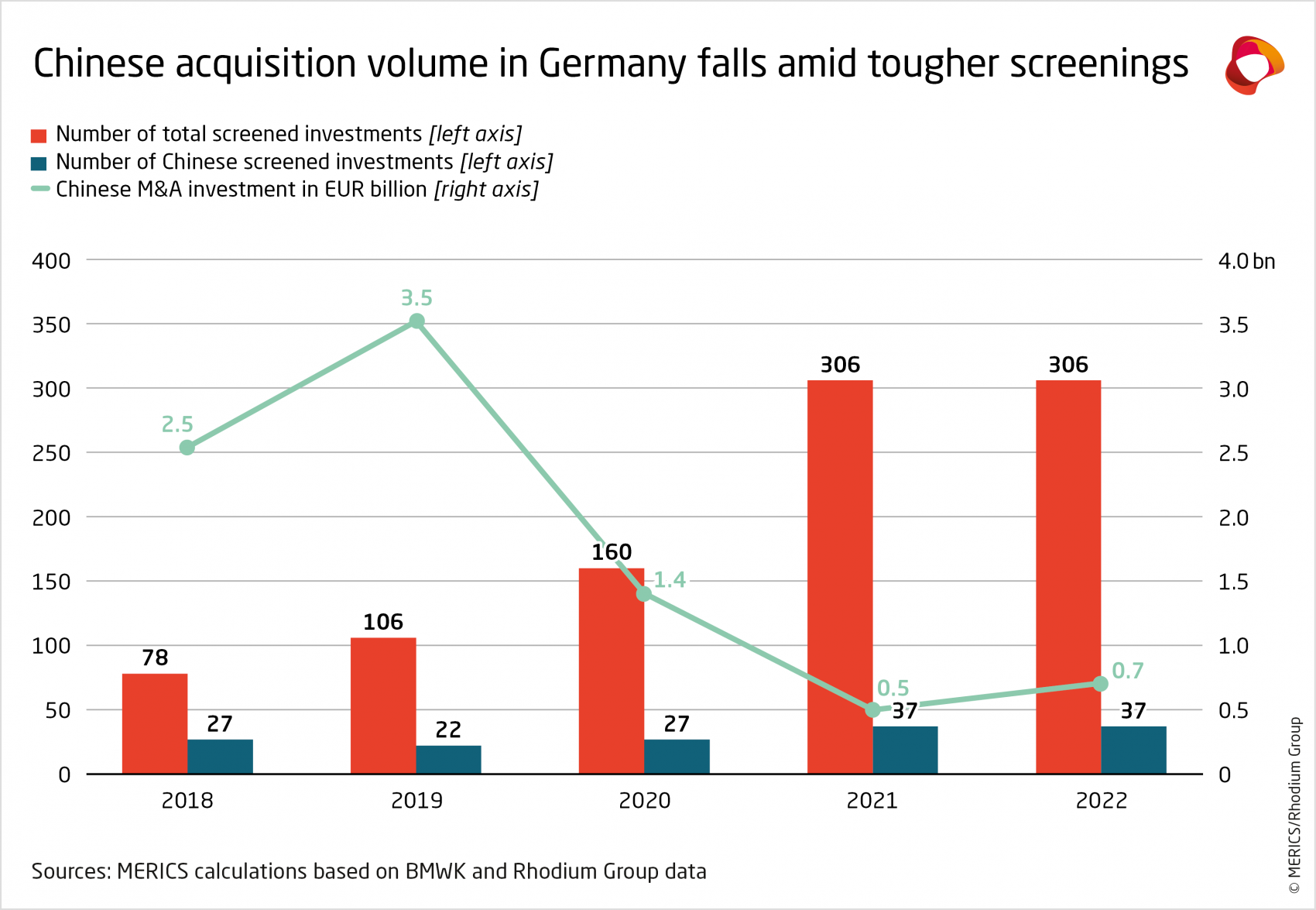

The German government has strengthened Germany’s investment screening regulation – the “Außenwirtschaftsverordnung” – several times since 2017 leading to an increase in the number of screened investments, including Chinese ones. This coincided with a downturn in Chinese M&A investment. While the total number of screened investments grew much faster than those of Chinese ones, there are indications, according to German media reports, that Chinese investments trigger particularly extensive screenings. At the end of March 2023, the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action had initiated in-depth reviews for 11 investments. Of those 10 were from Chinese investors and one from Russia.

Exhibit 13

4.2 European countries continue to adopt new screening measures

Increased scrutiny of inbound investment will likely continue in coming years. In 2023, review mechanisms will come into effect in Belgium, Estonia and Ireland, in the latter also with retroactive effect. The Netherlands is planning to launch a broader review system that will allow for reviews of sensitive technologies and energies, also with retroactive effect. And a Swedish mechanism is expected in 2024.

In its work report for 2023, the European Commission outlined its ambition to revise EU’s FDI screening regulation to strengthen its implementation and effectiveness. The Commission worries that EU screening mechanisms lack uniformity, including on scope of jurisdiction, review timelines, and notification measures.

A further strengthening of investment screening regimes could give Chinese investors greater certainty about red lines and hence help promote investment in non-sensitive areas. Yet this could be counterbalanced by the growing political pressure weighing on investment screening processes in Europe. Competence for investment reviews was just moved to the cabinet in the UK, de facto shifting decision-making power over (Chinese) investments from the administrative to the political sphere.

In Germany, too, Chinese investments – especially COSCO’s planned acquisition of a stake in a Hamburg port terminal – have been the subject of political controversy. According to media reports, the chancellor greenlighted a reduced COSCO stake, in opposition to involved ministries. The trend may deter Chinese investors as it limits their planning certainty.

4.3 The EU Commission toughens regulations on foreign subsidies

The EU will be rolling out a new mechanism to tackle subsidized foreign investments in 2023, which could target some Chinese investments in Europe in years ahead.

Until now, state aid controls have only applied to the EU’s internal market. Foreign subsidies were not subject to these rules. But in late 2022, the EU adopted the regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market, meaning that from July 2023, foreign investments (and other non-trade) activities in the EU will be subject to state aid controls. Foreign companies that benefited from subsidies in excess of EUR 50 million in the three years preceding an acquisition of a European company will have to notify the Commission if the acquired firm generates an EU turnover of at least EUR 500 million.

Given that certain Chinese investments in Europe have likely benefitted from some level of state support, not least subsidies, the new rules could create additional barriers. To circumvent the new requirements, the Chinese government could try to further obscure state support to Chinese companies, for instance in the form of below market equity investment or debt.

5. Outlook

While current low levels of Chinese investment in Europe mean a single large transaction could create a short-term bump in Chinese FDI in 2023, it is unlikely that Chinese FDI will make a sustained return to mid-2010 levels anytime soon. New and ongoing greenfield investments will put a floor under aggregate investment amounts, and interest in greenfield projects could rise as Chinese players set up EV manufacturing plants on the continent and Chinese manufacturers of other green technologies – like solar PV – look to Europe to avoid trade barriers. Yet these will not be enough to create a long-lasting rebound. Despite China’s relaxation of Covid-19 travel restrictions, there are few indications of strong pent-up M&A demand from Chinese investors. Instead, Chinese investors face headwinds from continued de-risking in China’s financial markets as well as turmoil in global markets, ongoing capital controls in China and the risk of further deteriorations in EU-China relations.

The most important factors that will shape Chinese investment flows to Europe in 2023 are:

In China:

- Chinese firms’ outward investment will vary heavily by sector: After three years of Covid restrictions, China’s economy will improve but the recovery will vary by sector and a structural slowdown is already baked in. Given persistent economic uncertainty, many Chinese firms will likely focus on domestic business consolidation in 2023 rather than outward investment. Still, in some sectors – like electric vehicles – a slowing domestic market could incentivize Chinese companies to go out and conquer new markets that require a presence on the ground.

- Beijing remains attentive to financial risks: The central government’s continued focus on managing financial risk creates additional headwinds for outward FDI, especially for highly leveraged firms. However, there might be certain sectoral exceptions, and certain players like BYD might be able to leverage earnings to finance overseas expansion plans.

- China’s tech players likely to cut down outbound activities to focus on domestic readjustment: While regulators have recently signaled that they will ease off on their multi-year tech regulation campaign, companies need to adjust to the new domestic market environment. Tech firms – important players in China’s outbound investment so far – are encouraged to prioritize strategic sectors and focus on capital intensive hardware and R&D. Overseas investment might take a back seat as they attempt to reach these officially mandated goals. The breakup of tech giants like Alibaba could also reduce the sector’s financial firepower for large acquisitions, making China’s tech firms more focused on smaller and more targeted deals.

- Beijing is now prioritizing inbound over outbound FDI to secure tech access: Beijing is now focused on cultivating inbound investment by foreign companies, as an equally effective means to attract foreign tech and IP. As such, the pressure to “go out” to acquire cutting-edge assets is reduced, and Chinese investors in Europe might focus instead on smaller deals and niche technologies, rather than high-profile billion-EUR takeovers as in the past.

In Europe:

- Strategic acquisitions will stay under scrutiny, even as Europe remains open to Chinese investment: The acquisition of sensitive technological and infrastructure assets has become more difficult for Chinese companies due to stricter European screening regimes. However, non-sensitive sectors still present opportunities for Chinese buyers. These include consumer-oriented assets, healthcare products or – at play in Southern Europe the past few years – energy assets.

- Europe will remain attractive to Chinese greenfield investment, especially in the auto sector: China’s strength in green technologies is a good match to Europe’s green agenda, regulatory moves that favor reshoring like the Critical Raw Materials Act, and significant local markets for green technologies. Greenfield investments in EV-related fields are likely to continue representing a substantial part of China’s FDI in Europe. Investors may branch out from battery module manufacturing into up- and downstream parts of the value chains. BYD’s hunt for an EV manufacturing site is indicative of the trend. Europe’s focus on resilience and decarbonization may also bring new opportunities in wind and solar energy. According to recent reports, GCL Technology one of China’s largest solar material makers, is considering investing in Europe. Restrictions on Chinese participation in green supply chains in other advanced economies could bind Chinese green tech investors tighter to Europe.

- A rapid deterioration of EU-China political relations is a possibility and could hamper investment: EU-China political relations have deteriorated in recent years, though they still leave room for constructive bilateral economic interactions, including inbound Chinese investment. Further deterioration in 2023 and beyond could increase political and administrative scrutiny of inbound FDI further. Factors that could trigger a further recalibration include Chinese military aid to Russia, coercive Chinese responses to new EU instruments or a major escalation over Taiwan could degrade Europe’s openness to Chinese investment.

- European legislation as double-edged sword for Chinese investors: The Foreign Subsidy regulation and International Procurement Instrument could constrain Chinese investment in Europe further. However, the Critical Raw Materials Act and Net Zero Industry Act could be a pull for Chinese green tech providers to localize and invest more.

Annex

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Annex 1

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Annex 2

![]() Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Hover over/tap the chart to see more details.

Annex 3