China's Currency Push

The Chinese Yuan expands its footprint in Europe

Main findings and conclusions

- Europe is at the forefront of Chinese efforts to grow the Renminbi internationally. China has set up many market access and trading infrastructure schemes in Europe, making it the largest CNY market outside of Hong Kong.

- The UK is the biggest player in Europe’s CNY market. The UK’s strengths – the world’s largest foreign exchange market and a business-friendly legal system – are hard to replicate. London is likely to remain Europe’s major CNY clearing center. However, Brexit may temporarily hurt the UK’s CNY business.

- Confidence in the CNY has been hurt by China’s capital controls, imposed in 2015, and the current unrest in Hong Kong. Capital controls preserved the CNY’s value but made investors wary about the ability to repatriate profits. Likewise, if China’s government were to interfere strongly to halt protests in Hong Kong, investors might feel their investments are under threat.

- European countries and businesses would benefit commercially from greater use of the CNY. China’s companies have limited access to foreign currency. Being able to make purchases in CNY abroad is appealing to them, and could result in more exports of European goods and services to China.

- A larger European CNY market also presents significant risks: European companies doing business in CNY could easily find themselves at the mercy of currency movements entirely decided in Beijing. Finally, a larger CNY market will facilitate Chinese foreign policy. As Europe is increasingly viewing China as a strategic competitor, this may not be desirable.

- European countries have competed with each other to attract CNY clearing business, so the necessary trading infrastructure is largely in place. International use of the CNY is being held back by restrictions on foreign access to China’s financial markets. There is room for more growth, but the pace is likely to be slow.

1. China wants to project power by expanding the reach of its currency

“Great powers have great currencies,” as Nobel Laureate Robert Mundell famously said.1

China’s currency remains far from fully convertible and internationally tradable, even though China is the world's second largest economy. The Chinese government’s ability to realize its declared dream of achieving great power status is hindered by this mismatch between the power of the economy and limited international use of its currency.

Numerous Chinese policy documents mention the need for the internationalization of the renminbi. China has made Europe a major focus of efforts towards this goal, so it is important that Europeans understand the likely trajectory of the growing CNY market.

This MERICS China Monitor looks at the strategic dilemmas for China’s policy makers in deciding how far and fast to internationalize the currency, before assessing potential commercial pathways. It weighs up the opportunities and current constraints on growth in CNY use and the implications for European interests. The current context of Brexit and protests in Hong Kong are also considered.

For the People’s Republic of China (PRC), transforming the CNY into an international currency would facilitate its foreign economic policy goals, bring immediate practical benefits and set up a self-reinforcing cycle of global influence and prestige.

Historically, having an international currency has helped countries to project power and develop distant spheres of influence. The UK and the US have shown how a first-tier international currency can help finance costly wars and economic interventions all over the globe. Financial reach and political strength are interlinked.

The PRC has pursued efforts to promote its currency. The current five-year plan (2016 – 2020) explicitly prioritizes the goal of improving CNY convertibility (the extent to which the currency can be exchanged for assets and goods) and mentions increased international use of the currency as a likely consequence. However, it sets out no detailed plans or targets. Initiatives to promote its currency in Europe also fit into China’s officially stated internationalization strategy.

European actors have proved receptive to working with Chinese partners to create an enabling infrastructure, as they can see the potential commercial benefits of CNY trading. China’s internationalization project has therefore gained traction in Europe, with substantial results.

Despite European receptiveness China itself is not always as forthcoming. China can never quite keep itself from making economic and financial matters political. Most recently cross-border listings on the new London-Shanghai Stock Connect were apparently halted in January 2020 due to political tensions over the protests in Hong Kong.2

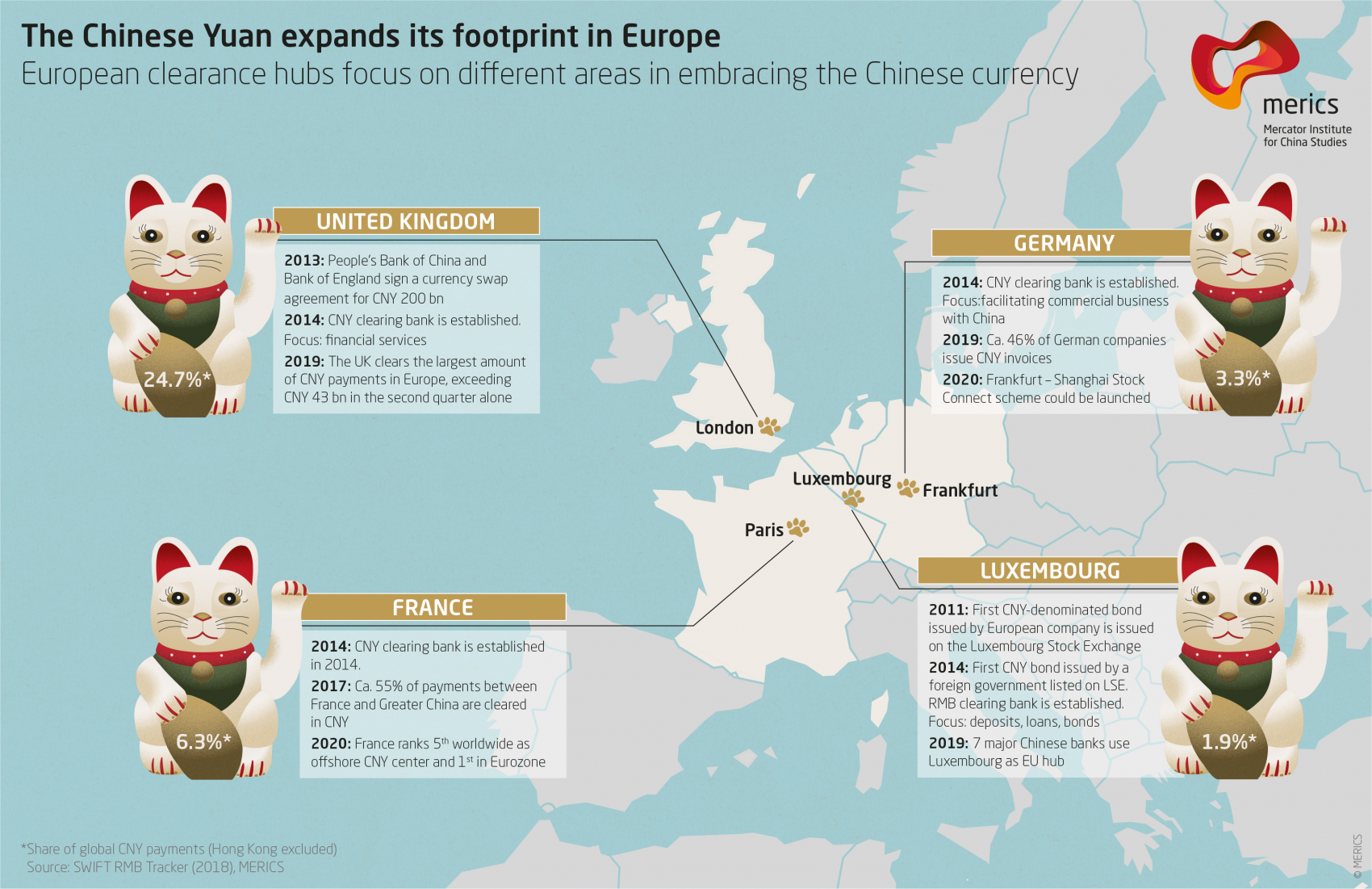

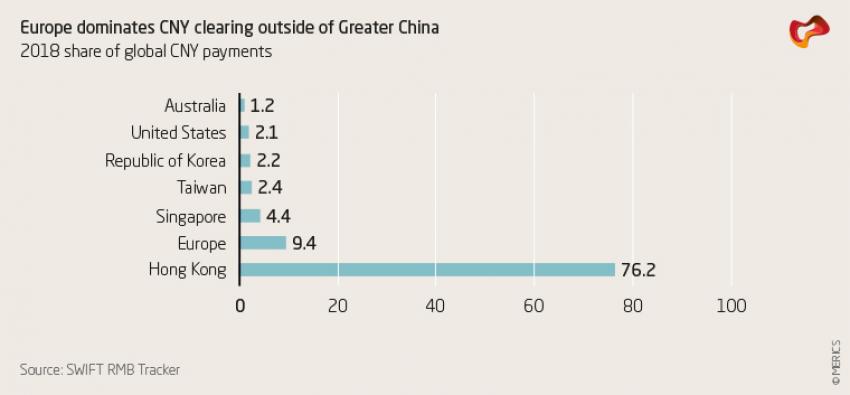

Outside of Hong Kong, Europe hosts the biggest CNY market. London is the world’s largest market for foreign currency and – unsurprisingly – the channel for the majority of European CNY clearing. Nonetheless, Paris, Frankfurt and Luxembourg have all carved out significant roles in the CNY market. However, international usage of the currency remains far below its potential, mainly because of China’s self-imposed restrictions on convertibility.

China’s leadership faces a broad strategic dilemma. Lacking a widely accepted international currency, China must pay its way in the world using the global currencies of other countries. An aspiring global power that cannot finance itself in its own currency runs the risk that foreign firms and institutions become reluctant to accept its currency as its foreign debt increases. Foreign banks may insist on lending in their own currencies.

The risks and limitations include forced curtailment of overseas investments and infrastructure projects from rising debt servicing costs, and exchange rate risk. Under extreme circumstances, access to funds could be restricted, e.g., through sanctions.

Chinese firms and state backed projects generate big bills that are largely US dollar denominated. For example:

- an overseas corporate buying spree, picking up everything from tech companies to lithium mines to golf resorts

- billions of dollars in infrastructure construction in Africa

- China’s costly ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ of international projects, one of the biggest foreign investment drives ever

- China is also among the world’s largest importers of oil and bulk commodities

China’s economic foreign policy is in effect dependent on the US currency and its financial system. Internationalization of the CNY would therefore assist China’s current economic foreign policy.

The current limited size of the CNY market is primarily a function of foreign investors’ limited access to Chinese financial instruments. As China constructs CNY trading infrastructure abroad, companies should become increasingly able to deposit CNY earnings into financial institutions that can then reinvest into China’s financial markets and further promote the use of the currency. There may be a boost to European exports as Chinese companies become able to pay for European goods in CNY.

2. China has made some progress towards internationalizing its currency

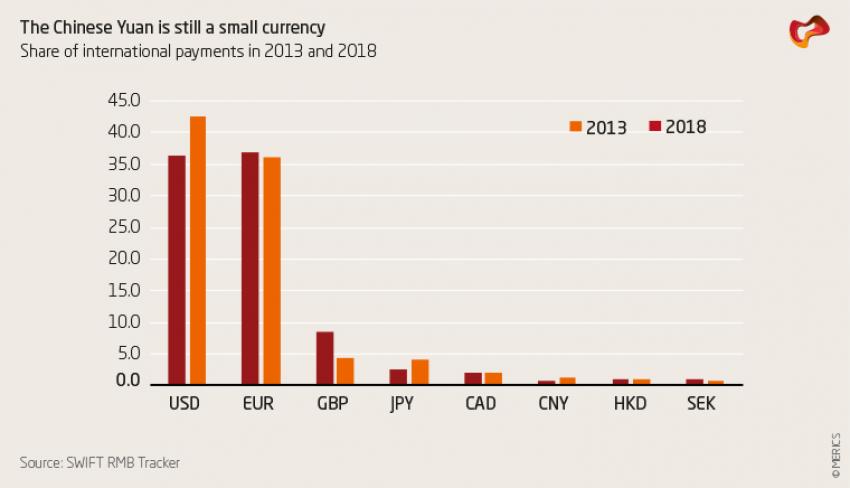

The CNY’s global usage has grown but still lags far behind other large countries’ currencies (see exhibit 1):

- The US dollar and the euro are massively dominant in global commerce, accounting in 2019 for more than three quarters of all global transactions, of which 42.5 percent were cleared in dollars and 36.2 percent in euros.

- The CNY is has become the fifth most used currency in global payments, after the British pound, the Japanese yen and the Canadian dollar.

- Nonetheless, its share remains tiny. The CNY’s annual average monthly share of global payments grew from roughly 0.8 to 1.2 percent between 2013 and 2018.

- The limited use of the CNY is striking because China is the world’s largest trading nation: approximately 12.8 percent of total global trade crossed the PRC’s borders in 2018.3

The CNY’s growth is partly due to the fact that China has made some progress in turning it into an international reserve currency. In 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) added the currency to the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, a move that signaled the Chinese currency was a suitable reserve. Since many central banks tailor the composition of their reserves in line with the SDR basket, the change led to greater uptake of the CNY.

Roughly one percent of global reserve assets were CNY-denominated by the end of the first year of the inclusion in the SDR basket. As the IMF did not track the CNY’s share of global reserve assets before 2016, it is impossible to make an accurate comparison with prior years. However, its share of global reserve assets had risen to 1.8 percent by the end of 2018. To put this in perspective, almost 62 percent of global reserves were in US dollar-denominated assets.

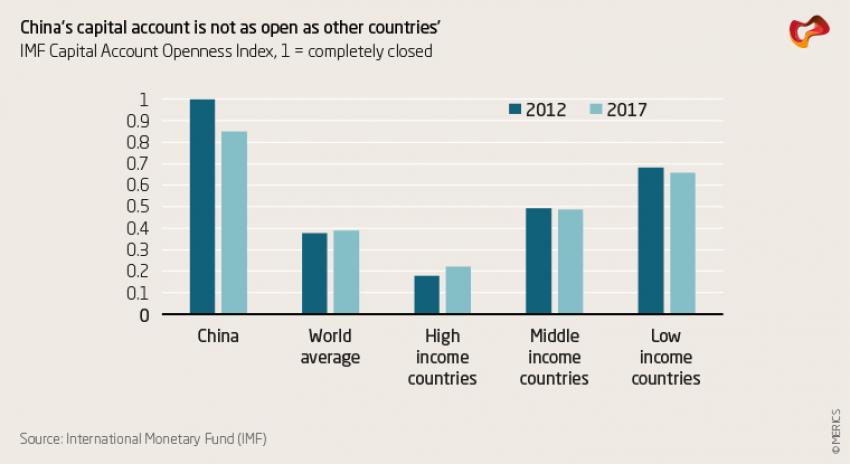

The still meager international usage of the CNY is due primarily to foreign investors’ limited access to China’s financial markets. In 2017, the International Monetary Fund’s capital account opening index ranked China at 0.85, where 1 is completely closed and 0 completely open. China’s capital markets are therefore among the hardest to access compared to both developed and emerging nations (see exhibit 2).

Investors are less willing to hold a currency with limited convertibility. As it cannot be readily exchanged for return-bearing assets, most market actors will prefer to receive relatively small sums. Larger sums pose considerable difficulties: many financial institutions lack the ability to handle larger amounts of CNY as China’s stock and bond markets can only be accessed through restricted schemes that not all investors qualify to use.

Restrictions on financial market access impact CNY-denominated capital and commercial flows: they are intimately related because of the circular way that international trade and investment works. Imagine water flowing through a circular pipe. Like damming up a river, putting a partial barrier into the pipe would reduce the volume of circulating water. Capital and commercial flows between countries operate similarly; a barrier in the capital side of the pipe also slows the commercial side.

A company that cannot freely convert earnings in a currency into return-bearing assets or financial instruments will be more reluctant to do business in that currency.

If China’s government were to remove restrictions on capital flows, it would help promote the CNY. However, the country’s leaders would have to sacrifice control of either monetary policy or the exchange rate. They wish to do neither.

Given these conflicting goals, China has not formulated an official CNY strategy. Some documents do exist, but none are official policy. It seems the CCP leadership cannot find a consensus. Officials frequently promise capital account opening, but progress has been slow. The current 13th five-year plan (2016 – 2020) states the goal to take systematic steps to realize CNY capital account convert ibility and to steadily promote its internationalization. It also pledges to support Hong Kong in improving its status and in strengthening its position as a global offshore CNY business hub.

A long list of payment infrastructure programs and conditional access schemes has evolved to support these aspirations. Examples of such measures include:

- access mechanisms to the Chinese financial system such as the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) program and the stock and bond connect mechanisms

- establishment of special clearing banks

- swap agreements with foreign central banks and greater protection of foreign investors

Such initiatives create pathways while being careful not to grant foreign investors into China equal access or rights. The conditional nature of these schemes allows the CCP’s leadership to make some limited progress in promoting China’s currency without losing control.

China has had success with such initiatives in many different markets such as Singapore and Korea. In Europe these initiatives have been warmly welcomed as a source of potential commercial benefits.

3. Chinese financial activity in Europe is growing in scale

European governments have helped to foster the development of the largest CNY market outside Hong Kong because they see the commercial benefits from increased use of China's currency.

London dominates CNY clearing. It has the world’s largest foreign exchange (FX) market, handling a daily average of 37 percent of all global FX deals in 2016. Plentiful expertise and financial infrastructure enable it to incorporate CNY trading into the mix. However, other European countries have become more proactive, too. The UK’s exit from the European Union may increase efforts elsewhere on the continent to do more business in CNY.

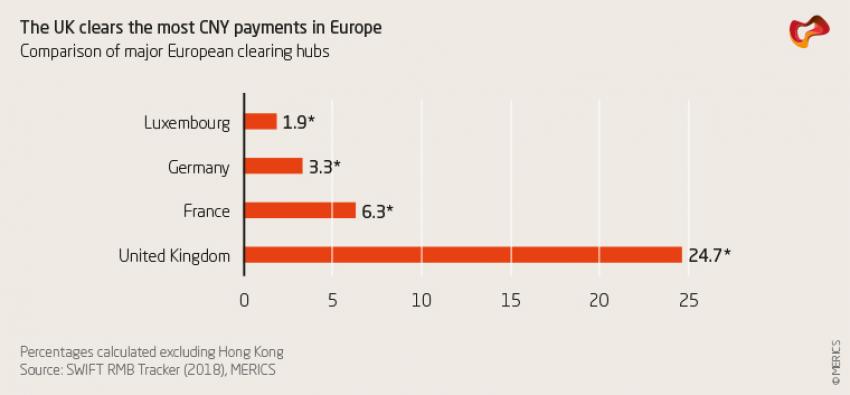

In 2018, a monthly average of 9.4 percent of global CNY transactions were cleared in Europe (see exhibit 3). The European share of the global total rises to 40.1 percent if Hong Kong’s CNY clearing is excluded from the data. Most of this, 24.7 percent, is cleared in the UK. For foreign exchange trades involving CNY, the European share is even greater.

There are several reasons why China has chosen to focus its CNY internationalization efforts in Europe:

- The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Connecting the eastern and western parts of the Eurasian landmass is a key goal of President Xi Jinping’s flagship project. Chinese companies and their partners must fund and pay out for construction of the vast BRI network of ports, roads and railways. Currently, they must first acquire dollars. It would be easier for them if their European partners accepted CNY payments. Many official documents for European CNY internationalization projects make this link.

- Business convenience: In 2018, China imported goods from Europe worth more than two trillion USD, roughly 18 percent of the PRC’s total imports. Specialized goods such as high-quality machine tools are in high demand, as are European professional and financial services. The European CNY market makes trade easier for Chinese companies by enabling direct payments for European goods and services.

- Ease and receptiveness: The scale and network effects provided by its large and cohesive markets makes growing a foreign currency easier in Europe than most other places. Taken together, the EU accounts for about 21.9 percent of global GDP,4 making it the world’s second largest producer after the US. The single market provides cohesion; there are hardly any financial or commercial barriers between the economically diverse member states. European companies and institutions are accustomed to doing business in multiple currencies: trade revenues deposited in Paris can readily be exchanged for another currency in Frankfurt then invested in financial instruments in London.

European spheres of influence are also geographically far removed from China, giving rise to fewer strategic conflicts than for Pacific powers like the US and Japan. This partly explains why European governments have been less worried about potential risks stemming from cooperation with China and tended to focus more on commercial benefits.

3.1. Europe’s export-oriented economies can gain from internationalization of the Chinese Yuan

European governments and institutions have good reasons to be receptive to China’s CNY internationalization initiatives. Their economies are far more export-dependent than the US. Merchandize trade in 2018 made up 71.2 percent of German GDP, 45.2 of French GDP and 41 percent for the UK5, whereas it was only

20.8 percent of US GDP. Exporting such large quantities is impossible without receiving payments in other countries’ currencies. European leaders safeguard European business interests by facilitating the healthy development of foreign currency markets (see exhibit 4).

European regulators and financial institutions have cited pragmatic accommodation to business needs as reasons to promote the growth of the CNY market. Sherry Madera, until recently the City of London Corporation’s special advisor for Asia, has stressed the importance of London’s growing links with China6 for the global future. Hubertus Vaeth of Frankfurt Main Finance and former head of Asian research at Deutsche Bank, has taken a similar view: “Frankfurt has a once in a lifetime opportunity: we are witnessing the emergence of a new global currency.”7More pragmatically, the French consul general in Hong Kong, Arnaud Barthelemy, has emphasized8that French companies want to settle trade in CNY and French banks to offer CNY-denominated bonds and funds.

European receptiveness has encouraged China to be particularly active in setting up initiatives to promote CNY business here. CNY clearing banks have been established, and memoranda of understanding for development of financial infrastructure signed. European financial organizations have been granted access o Chinese financial products through the RQFII program, and Chinese banks have established themselves in Europe.

The two European central banks in charge of the majority of European markets where the CNY is traded have signed currency swap agreements. Both the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BoE) have signed large swap agreements with the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Such agreements are for loans between central banks in their respective currencies. They help promote CNY lending by guaranteeing a basic level of liquidity in the market. Speaking in 2019, former BoE governor Sir Mervyn King described the swap agreements as one of the most important steps towards promoting CNY business in London.9

3.2. European countries take different approaches to establishing Chinese Yuan markets

The four European countries that cleared the largest share of global CNY payments in 2018 were the UK, France, Germany and Luxembourg, though they played different roles (see exhibit 5):

- The UK handles the largest amount of CNY payments in Europe: in 2018, it cleared a monthly average of 24.7 percent10of CNY transactions (Hong Kong removed).

- Nearest rival France cleared 6.3 percent; Germany 3.3 percent; and Luxembourg 1.9 percent.

Each country is strong in different segments of the CNY market. As Nicolas Mackel, chief executive of Luxembourg for Finance has said: “London leads in foreign exchange, Germany in trade, but for investment and deposits Luxembourg is the place”.11 European countries’ efforts to build CNY markets have not been identical. Some have increased the amount of goods trade invoiced in CNY, while others have focused on developing CNY-denominated financial products, and some also offer deep FX markets. That said, all the top CNY trading countries in Europe are to some extent active in all these avenues.

United Kingdom

The UK clears the largest amount of CNY payments and FX transactions. It has a large trade deficit with China, and exports less to China than either France or Germany in absolute terms. In 2018, the UK exported 23.8 billion USD worth of goods to China but had a trade deficit of 33.4 billion USD.12Aided by a business-friendly legal system,13the UK’s large financial and currency markets make up for the smaller amount of trade. In 2014, the UK exported 20 billion GBP worth of financial services to the EU.14European financial markets are open, so companies that earn CNY in other countries can deposit or exchange it in London. The UK financial system then allocates it elsewhere. This network effect makes London an attractive deposit destination for companies from all over Europe.

While the effects of pending Brexit on London’s future role in CNY internationalization are still difficult to assess, China’s January 2020 suspension of the new London-Shanghai Stock Connect has demonstrated how politicized the space of financial cooperation with China still is. According to sources quoted in the media, tensions over Britain’s stance on the protests in Hong Kong caused China to temporarily block the stock connect scheme which had just been launched in 2019 with the aim of attracting more CNY business to the UK.

The stock connect allows equity traders in both cities mutual market access through depositary receipts. This enables London-based financial institutions to buy China-listed, RMB-denominated shares. The connect is also intended to allow Chinese firms to directly list newly issued shares denominated in GBP and USD on the London Stock Exchange, thereby helping them to finance themselves in foreign currencies.

Germany

The country initially hoped to establish Frankfurt as the leading European clearing and settling hub for real-economy based business. This focus makes sense as trade in goods dominates Germany’s economic relationship with China, far more so than for the UK and France. But the vision has not yet come to fruition. According to the monthly CNY tracker run by SWIFT’s, the world’s largest payment systems provider, only a small share of Sino-German trade is settled in CNY, with most business still done in other currencies. This is likely because banks that already have other channels (for example through Hong Kong or other European countries) are reluctant to use the clearing center.15

CEINEX is a Sino-German joint venture, an exchange for Chinese financial products between the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Deutsche Börse. Located in Frankfurt, CEINEX allows Chinese companies to list ‘D-shares’, i.e. euro and CNY-denominated shares sold on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. However, only Shanghai-listed companies with A-shares can list on the Frankfurt exchange. So far, most business has been conducted in euros. In 2018, only 3.5 percent of trades were in CNY. The most notable company to list shares through CEINEX was the white goods maker Qingdao Haier.

France

France clears the second largest amount of CNY in European markets, under a strategy that sits halfway between that of Germany and the UK. Much of French trade with China is conducted in CNY. More than 55 percent of payments between France and China/HK were cleared in CNY in 2017, according to the SWIFT CNY tracker. But France’s FX market is smaller than the UK’s. In 2016, it handled some 2.7 percent of global FX trades and around six percent of FX trades involving CNY.

Luxembourg

The city-state focuses on deposits, lending and bonds and has Europe’s largest pools of CNY deposits, loans and bonds.16It has competed for CNY market share by allowing Chinese banks to set up subsidiaries shipping in their own capital from abroad. Luxembourg’s eurozone membership and ability to offer the European banking passport (which allows banks domiciled there to do business in all member states of the European Economic Area, EEA) offset its small size. The strategy has proved successful: China’s major state banks (except for Bank of China) have established their European HQs in Luxembourg.

Despite London’s dominance, efforts to build CNY markets in continental Europe will continue. Joachim Nagel who served on Deutsche Bundesbank’s executive board from 2010 to 2016, has said17that euro clearing for CNY business should be located in a country which is part of the euro system, as any other arrangement “would not give the best signals.“

However, it will be hard for continental European countries to unseat the UK as the top CNY market without restricting capital flows. The UK has advantages other countries cannot easily compete with: a business-friendly legal system; the world’s largest FX market; a historical connection with Hong Kong (where British banks are common); an English-speaking environment that is easier for Chinese companies to work in and – perhaps most importantly – the sheer size and connectivity of its financial markets. As continental European players cannot simply replicate these advantages, mounting a firm challenge to London would imply self-defeating measures such as restrict their own businesses’ access to the UK markets.

It is very unlikely that capital controls would be imposed, as they are an infringement on property rights hardly ever used by democratic countries. Any restriction on capital flowing between the European mainland and the UK would effectively restrict EU savers and investors to the returns offered there. (Two democratic countries that resorted to such exceptional and temporary measures were Argentina in 2019, and Greece in 2015.) Without capital controls, CNY can still be freely deposited in the UK.

Brexit may take some business away from the UK but is unlikely to push it off the top spot. If on leaving the EU, the UK also quits the EEA – which seems likely – it will lose European banking passport rights that allow UK-based banks to sell financial services directly and actively to EU-based customers. The UK would then have to apply for separate licenses in each member country and find middlemen to work with.18But even without the banking passport, EU-based companies would still be able to buy interest-bearing products directly from UK banks by seeking them out. European companies that earn CNY from trade would therefore still be able to deposit those revenues in London.

4. CNY markets will continue to grow despite obstacles and uncertainties

The joint efforts of European and Chinese players are likely to produce an expanding market for CNY and its greater use as an international currency. Europe increasingly possesses the necessary trading infrastructure. But considerable barriers remain.

China’s policy conundrum is the main obstacle: like a cat lingering on the threshold, it cannot decide if it wants to go out or in. It wants the benefits of internationalizing its currency but wishes to retain complete control over its economic relations with other countries, two goals that are incompatible.

China has not been able to formulate an economic policy accommodating enough to transform the CNY into an international currency. The currency pipeline connecting Europe and China remains clogged, letting only part of the possible flow through. Access restrictions, government interference, and market conditions on the Chinese side are the main barriers to rapid currency flows between Europe and China.

In times of crisis, China has proved willing to take a step backwards. A recent example was the government’s 2015 decision to impose capital controls. Their aim was to stabilize the currency’s value by prohibiting many CNY flows out of China. Both finance professionals and government officials interviewed for this MERICS China Monitor have suggested it was a backward step for CNY internationalization. Political unrest in Hong Kong is also an important factor with unknown consequences for CNY markets. The outcome of protests against mainland China’s growing influence remains unknowable, as the situation is volatile and poses complex challenges. If China’s leadership opts for heavy-handed solutions, investors may flee Hong Kong, hurting all global CNY business.

5. Conclusion: Europe can benefit from a larger CNY market, but there are also risks

A larger European CNY market could bring commercial benefits. It might even give Europe more leverage over China’s economic policies. But it also presents significant risks. European companies doing business in CNY could easily find them- selves at the mercy of currency movements entirely decided in Beijing. Finally, a larger CNY market will facilitate Chinese foreign policy. As Europe is increasingly viewing China as a strategic competitor, this may not be desirable.

The growing CNY market will make it more convenient for Chinese companies to buy European goods, and European demand for the currency will increase as more CNY-denominated financial products become available. More goods and capital flows between Europe and China are likely to bring increased business opportunities for European companies, boost European exports to China, increase Chinese liabilities to Europe, and lower the trade deficit.

However, it may be problematic for European businesses to have large exposure to CNY assets. China’s exchange rate regime is opaque. On paper, the CNY is pegged to a basket of different currencies but trends suggest that the peg is loose at best. European companies could find their investments subject to arbitrary exchange rate movements driven more by policy in Beijing than by economic outcomes.

There are potential political benefits from an expanded CNY market. As a country’s currency pools outside its borders, its liabilities increase. Creditor countries may find themselves more able to influence China’s policies.

They may even find they can wield influence through threats to reduce lending unless congenial policies are implemented.

Facilitating China’s foreign policy poses a severe risk to European interests. As the CNY market grows, so does China’s ability to finance itself abroad in its own currency. It will be better able to finance influence-shaping projects such as the Belt and Road, and to purchase foreign enterprises. Just as it has for the US and UK, an international currency will also improve China’s ability to finance foreign interventions.

Whether Europe should continue supporting the growth of the CNY market depends largely on how China is viewed. Is it a distant power, full of economic opportunity, whose geostrategic goals do not overlap much with Europe’s? If so, then building the CNY market offers commercial benefit without hurting European interests. By contrast, if China is regarded as a strategic competitor with many interests in potential and increasing conflict with Europe’s, then there is a stronger case for caution.

- Endnotes

-

1 | Mundell, Robert (1993). “EMU and the International Monetary System: A Transatlantic Perspective,” Austrian National Bank Working Paper 13 (Vienna).

2 | Julie Zhu, Abhinav Ramnarayan, Jonathan Saul. “China halts British stock link over political tensions – sources”. Reuters Business News, 2 January 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britain-ipos-exclusive/exclusive-china-halts-british-stock-link-over-political-tensions-sources-idUSKBN1Z108L Accessed: January 6, 2020.

3 | UN Comtrade | International Trade Statistics Database. https://comtrade.un.org/ Accessed: January 6, 2020.

4 | World Bank Open Data | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/ Accessed: January 6, 2020.

5 | World Bank Open Data | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/ Accessed: January 6, 2020.

6 | City of London & The People‘s Bank of China. „London RMB Business Quarterly“. Issue 1. 2018.

7 | “Germany and the RMB Roundtable: Waving the flag for the eurozone” Global Capital. 2014.

8 | Yiu. E. “France out to build on gains as yuan hub, consul general in Hong Kong says” SCMP. 2014

9 | Event, China’s Future Role in the Global Financial System. March 14, 2019. Enodo Economics. London

10 | SWIFT. RMB Tracker. https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/compliance-and-shared-services/business-intelligence/renminbi/rmb-tracker/document-centre Accessed: January 6, 2020.

11 | “London leads in foreign exchange, Germany in trade, but for investment and deposits Luxembourg is the place”. The business report. 2015

12 | CEIC Database. Accessed: January 6, 2020.

13 | La Porta. Et al.”The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins” Journal of Economic Literature, 46:2, 285 – 332. 2008

14 | Bba. ”What is ‘passporting’ and why does it matter?”. Brexit Quick Brief #3. 2016

15 | Atzler, E and Slodczyk, K. „Frankfurt’s Yuan Venture a Flop“. Handelsblatt. 2016

16 | PWC. “Where do you Renminbi?” PWC. 2014 https://www.pwc.lu/en/china/docs/pwc-wheredo-

you-renminbi.pdf Accessed: January 6, 2020.

17 | “Germany and the RMB Roundtable: Waving the flag for the eurozone” Global Capital. 2014

18 | Bba. ”What is ‘passporting’ and why does it matter?”. Brexit Quick Brief #3. 2016