"Comprehensive National Security" unleashed: How Xi's approach shapes China's policies at home and abroad

Main findings and conclusions

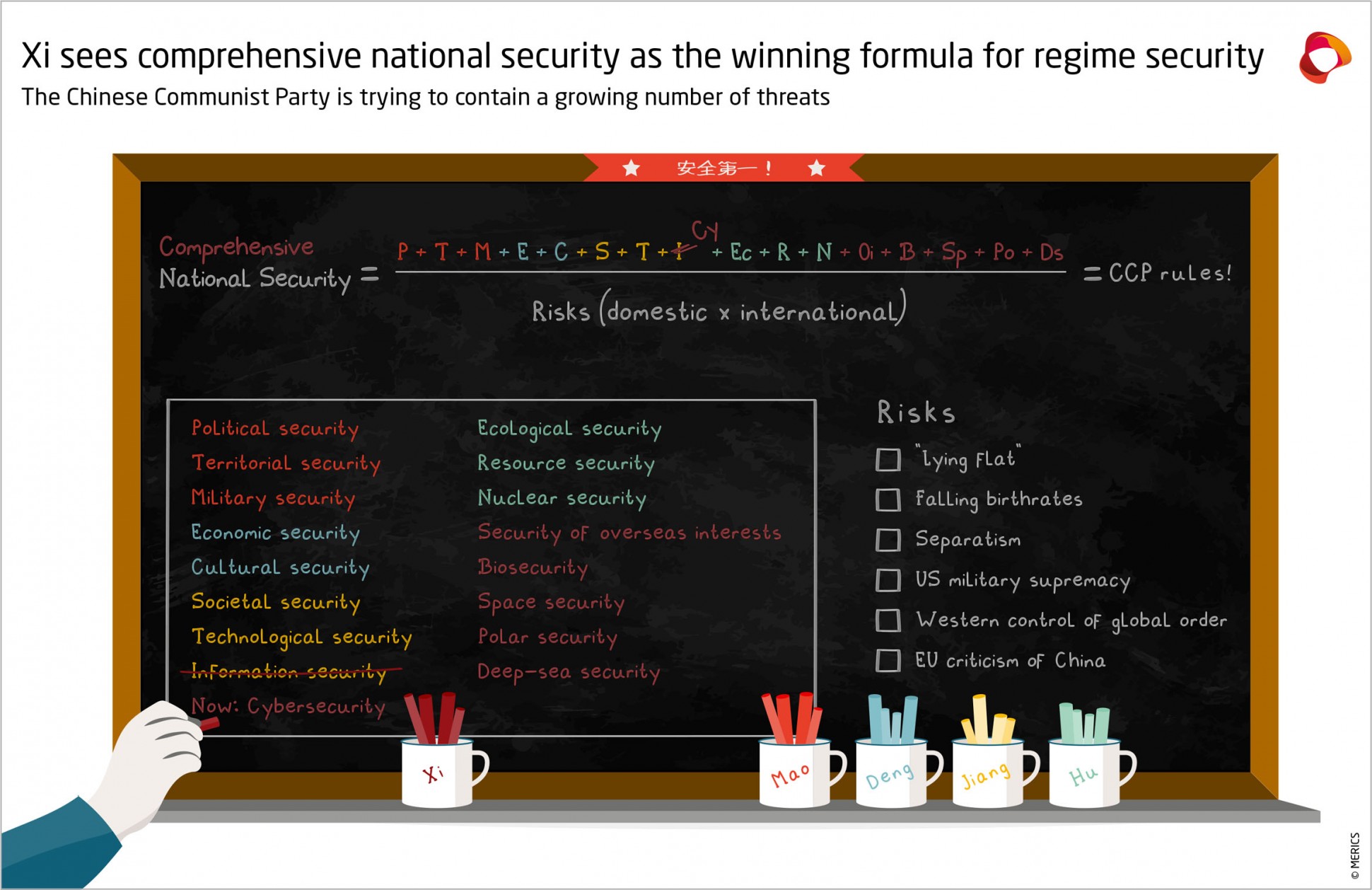

- Xi Jinping has turned national security into a key paradigm that permeates all aspects of China’s governance. His expanding “comprehensive national security” concept now comprises 16 types of security. Xi has also formalized new implementation systems – from laws and regulations to institutions and mass mobilization campaigns.

- This new focus on keeping China safe is driven by perceptions of internal and external threats. It also serves as a strategy to hedge legitimacy risks and ensure continued support for the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) rule as China shifts away from a development-first model.

- Xi’s national security outlook builds on the legacy of previous leaders. From Mao to Xi, China’s leaders have continuously added new types of national security, but the overarching mission has remained to defend the CCP’s hold on power and political stability.

- Xi’s quest for a comprehensive national security formula has reshaped China’s policymaking. The result is a state of hyper-vigilance with wide-reaching effects on state-society relations, China’s economic growth model and how the leadership enforces its interests abroad.

- The all-encompassing national security mindset is increasingly locking China into certain modes of action. By priming officials and citizens to be ever-alert to potential threats, pragmatism has given way to ideology, heightening the risk of overreaction and arbitrariness.

- This “securitization of everything” extends beyond Xi’s tenure and will continue to define China’s domestic and international behavior until there is a substantial ideological shift. This new paradigm implies clear – and new – risks and challenges for governments, businesses and non-state actors engaging with China.

- The trend towards the “securitization of everything” will likely accelerate. However, domestic criticism reveals it is not uncontested and party-state actors are still assessing the risks to China’s economic development and international standing.

- Foreign actors can seek to change the party’s calculus by communicating concerns. Targeted and coordinated responses can help raise awareness in the Chinese policy- making apparatus and upping the cost of harmful behaviors.

1. Introduction

New, wider definitions of national security are emerging in many countries. However, China’s party and state leader Xi Jinping has turned national security into a goal in itself: his all-encompassing view of national security has become a core element of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) world view and governance model. Amid rising tensions with Western nations, complicated by Russia’s war in Ukraine and global supply chain problems, this paradigm heightens the risk of overreactions.

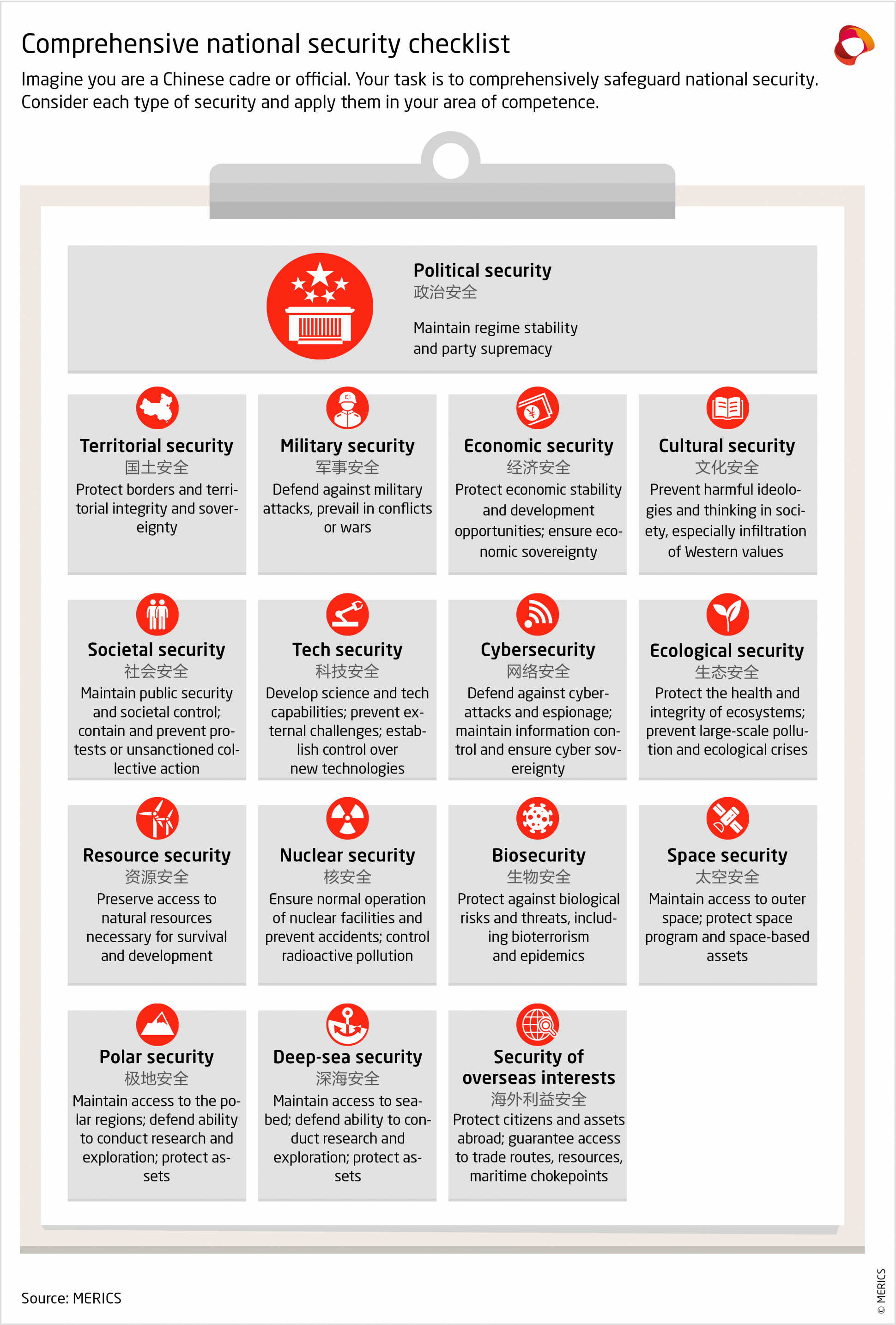

Xi’s concept of “comprehensive national security” (总体国家安全) was officially introduced in 2014 and now comprises 16 security arenas deemed essential to China’s development and the party state’s survival by keeping China domestically stable and internationally thriving. The concept is closely linked to achieving the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by 2049 and has been encoded in the revised Party Constitution and various party documents and laws.1

The November 2021 “historical resolution” from the CCP Central Committee’s sixth plenum warned of unprecedented pressures from an increasingly fraught international environment that blends traditional and non-traditional threats.2 In late 2021, the Politburo also drew up a new National Security Strategy for 2021–2025.3 The document is not public but reinforces existing policies. As Xi instructed top officials of the CCP’s security and legal apparatus in January 2022: all party and state organs must improve their efforts to prevent and contain any internal and external threats to China’s national security and political system.4

The hallmark of the Xi era is the party’s potent mix between confidence and paranoia when it comes to national security. The CCP’s threat perceptions have risen, fearing that internal and external forces may subvert its hold on power. It feels besieged by the US and Western countries, intent on containing China. However, the party state is also increasingly confident of its domestic organizational and institutional abilities, and capacity to project power globally – strengths it believes will help it detect, contain or preempt threats before they do substantial damage.

This confidence is driven by the CCP’s conviction that China has the more stable, superior political model: the leadership has repeatedly contrasted “chaos in the West and order in China”, as expressed in the initial rhetoric around China’s “victory over Covid” – even if its “zero-Covid” policies are now causing significant economic harm.5 Nonetheless, the CCP’s new confidence informs policy choices and helps explain China’s more aggressive conduct in recent years.

This “securitization of everything” is not a temporary phase: Xi’s qualitative changes to China’s national security framework are built on established concepts and institutions set up by his predecessors. Beijing’s preoccupation with threats – real or perceived – will continue to shape its domestic and international behavior, especially as increased geopolitical competition with the West and the CCP’s 20th party congress put cadres and officials on high alert.

This new paradigm implies clear – and new – risks and challenges for governments, businesses and non-state actors engaging with China. Governments and businesses face a China that is more willing to accept economic costs to defend its stability and broad understanding of national security, including through economic coercion. Efforts to decrease reliance on the West and competition in the tech sector will intensify. Foreign companies are exposed to new legislation and political pressure.

As Beijing becomes more assertive in enforcing its red lines, this means loss of access for foreign journalists and other non-state actors, but also risks of hostage diplomacy cases and sanctions.6 The recent crisis around US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan further highlights the risks of escalation and military conflict in the region derived from Beijing’s approach to national security.

2. Xi has turned national security from policy goal into mode of governance

Xi has made national security into a core component of party ideology, a state doctrine that permeates all aspects of China’s governance. Today, national security work in China is not only meant to avert threats but to proactively identify any potential new threats – domestic and international – that the party must adapt to. This has spurred a rapid expansion of what is considered a matter of national security. The expansion is not one of mission creep, but rather takes place by design.

Building on the legacy of previous leaders, Xi has driven substantial conceptual and organizational changes, in the form of new laws and regulations, and has upgraded institutions with more manpower. Even if Xi were to give way to a new generation of leaders, the “securitization of everything” will continue to shape policy unless there is a substantial ideological change of course.

2.1 What Xi’s concept of national security entails

In response to fears of greater global and domestic instability, Xi sought a unifying theory that combined internal and external security concerns and guided policy choices across the board. This serves to ensure the party’s continued hold on power, but also to hedge legitimacy risks at a time of slowing economic growth. Collective security, meaning a tightly controlled but stable society, and the goal of a strong China inspiring national confidence and international respect, have become key promises to the people.

Xi articulated the “comprehensive national security” concept in 2014.7 Originally encompassing 11 types of security, the set has now expanded to 16 (see Exhibit 4), adding areas such as biosecurity and space security. The publication of Xi’s collected speeches on comprehensive national security in March 2018, followed by a compendium in 2022, epitomizes efforts to turn the concept into party canon.8

A hierarchy of security types exists in Xi’s theoretical framework. Political security, i.e., safeguarding China’s party state, is the “bedrock” (根本). Economic security is the “basis” (基础). Military, cultural and social security are the “guarantees” (保障) – meant to help avert danger before it materializes. New domains such as cybersecurity and maritime security are described as urgent tasks.9 Promoting the security of China’s overseas interests is the last piece of the puzzle. Achieving security across issue areas in turn helps uphold political security.

National security and stability are now framed as the highest political priority and preconditions for continued economic development.10 Beijing’s vision for a new global security order rests on the same equation. In May 2022, Xi proposed the Global Security Initiative (GSI) – closely linked to China’s 2021 Global Development Initiate (GDI) – to promote China’s “wisdom and solutions” and “solve global problems.”11 While the GSI and its role in the global security architecture is still taking shape, the “security” in its name implies Beijing’s emphasis on state sovereignty, regime stability and collective security. Described as an extension of Xi’s comprehensive national security outlook, it may provide affiliated states with a wide remit to justify almost any action under the banner of security, and heralds a further clash of international norms.

2.2 From Mao to Xi, party priorities show continuity in change

Xi Jinping’s concept of “comprehensive national security” did not emerge out of thin air. It follows a continuous expansion that dates to the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 (see Exhibit 1).12 This process is one of continuity in change, as the party gradually shifted its focus from traditional to non-traditional security. Yet the overarching goal – defending the CCP’s hold on power – has been constant and rests on the core conviction that only the CCP can return China to its rightful place in the world.

The CCP under Mao Zedong was largely preoccupied with China’s territorial and military security. Under Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, China opened up to the world at a time of global economic growth and industrial modernization, foregrounding issues of economic security. The 1989 Tiananmen protests triggered a new emphasis on cultural or ideological security, and societal security, to prevent fundamental challenges to the regime. Further adaptations came under Hu Jintao, who introduced and prioritized ecological and resource security, amid widespread protests over severe pollution and deficient labor protections.

Xi has significantly accelerated this trajectory. The spotlight has shifted to controlling information flows and preempting networked resistance, as well as to ensuring China’s economic, technological, and geopolitical leadership. Corruption and party discipline have also been high on the agenda under Xi – both to address public loss of trust and target internal rivals and resistance to key policies.13

Military and territorial security have remained central but are now pivoting to defending the PRC’s claims in the South and East China Seas, and compete with the United States for primacy in the Indo-Pacific. “Reunification” with Taiwan – by whatever means – has been given unprecedented urgency by linking it to the second centenary goal of achieving China’s “national rejuvenation” by 2049.14 It signals growing intransigence in Beijing on anything related to Taiwan’s future or status.

2.3 Xi has upgraded legal and institutional support systems

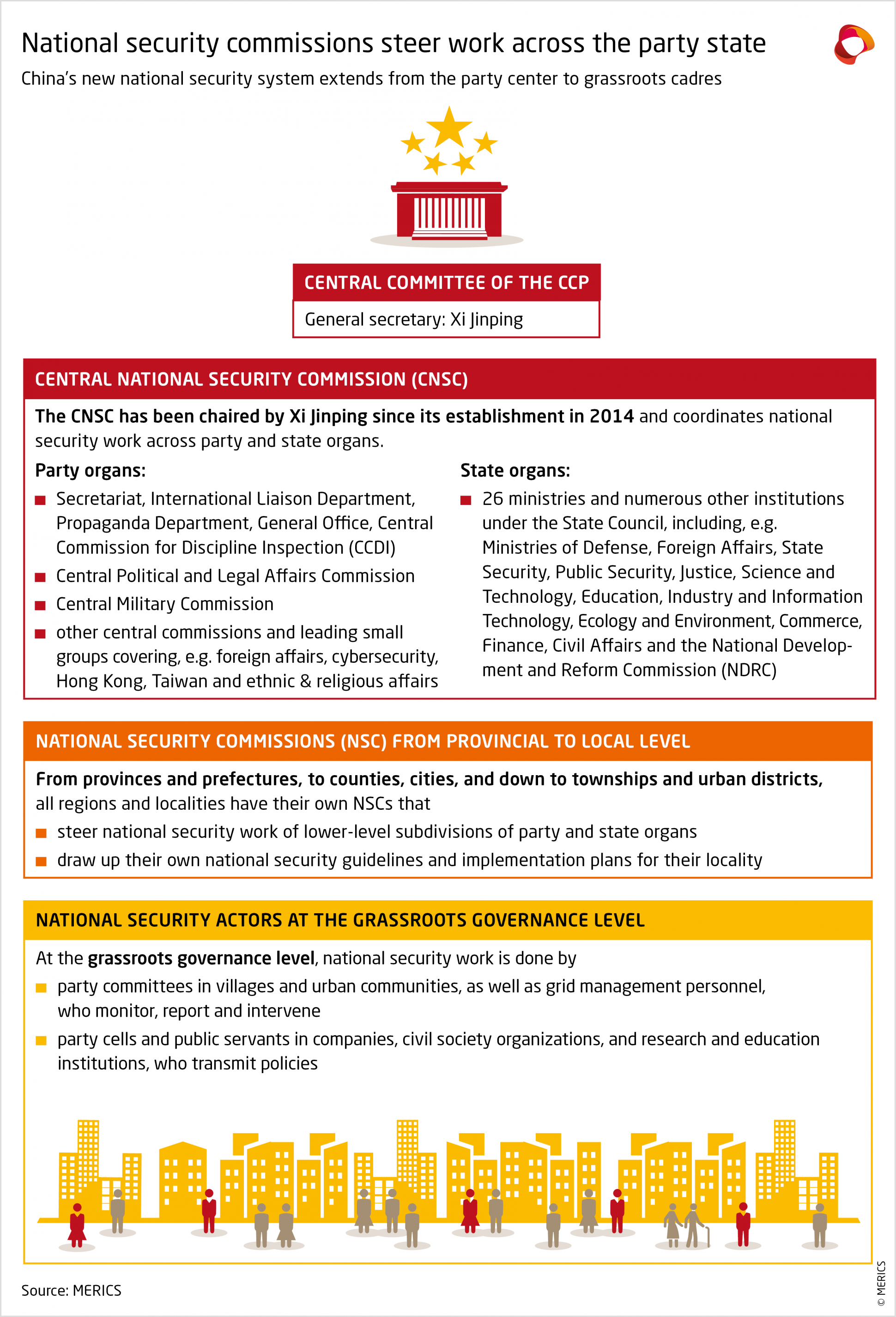

Today, the party sits atop a web of national security commissions that have been established or upgraded across the administration, from central to local levels (see Exhibit 2). The party transmits its priorities and agenda through these commissions.15 They fulfill a coordinating function and ensure that nearly all state ministries, departments and government-funded organizations take part in safeguarding security in some way. Party organizations, too, must help uphold national security, down to party cells in education, the private sector and civil society. This framework keeps cadres and public officials on the lookout for potential threats.

Here, too, Xi has built on the legacy of his predecessors. In the Mao era, national security work remained the purview of the military and the security services, while political tensions and opposition were dealt with through political and mass mobilization campaigns. Deng gave formalized roles to additional institutional actors, ranging from economic ministries and departments to media organizations, which were tasked with being “ideological centers for promoting nationwide stability and unity.”16

In 1997, Jiang tried to establish a National Security Commission, modeled on the US National Security Council, to coordinate across the rising number of party organs and state agencies involved in national security work. His idea was partially rejected, resulting in a compromise – the Central Leading Small Group (LSG) on National Security set up in 2000, with sub-organizations at lower party-state administrative levels.17

In late 2013, Xi upgraded the LSG into the Central National Security Commission (CNSC), the new pinnacle of China’s national security apparatus. Now at the end of his second tenure, Xi not only oversees the CNSC and other commissions related to key national security areas, but he has also successfully placed trusted cadres like Ding Xuexiang, Head of the CNSC Office, Chen Yixin, General Secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, and Wang Xiaohong, China’s new Minister of Public Security, in key positions.18

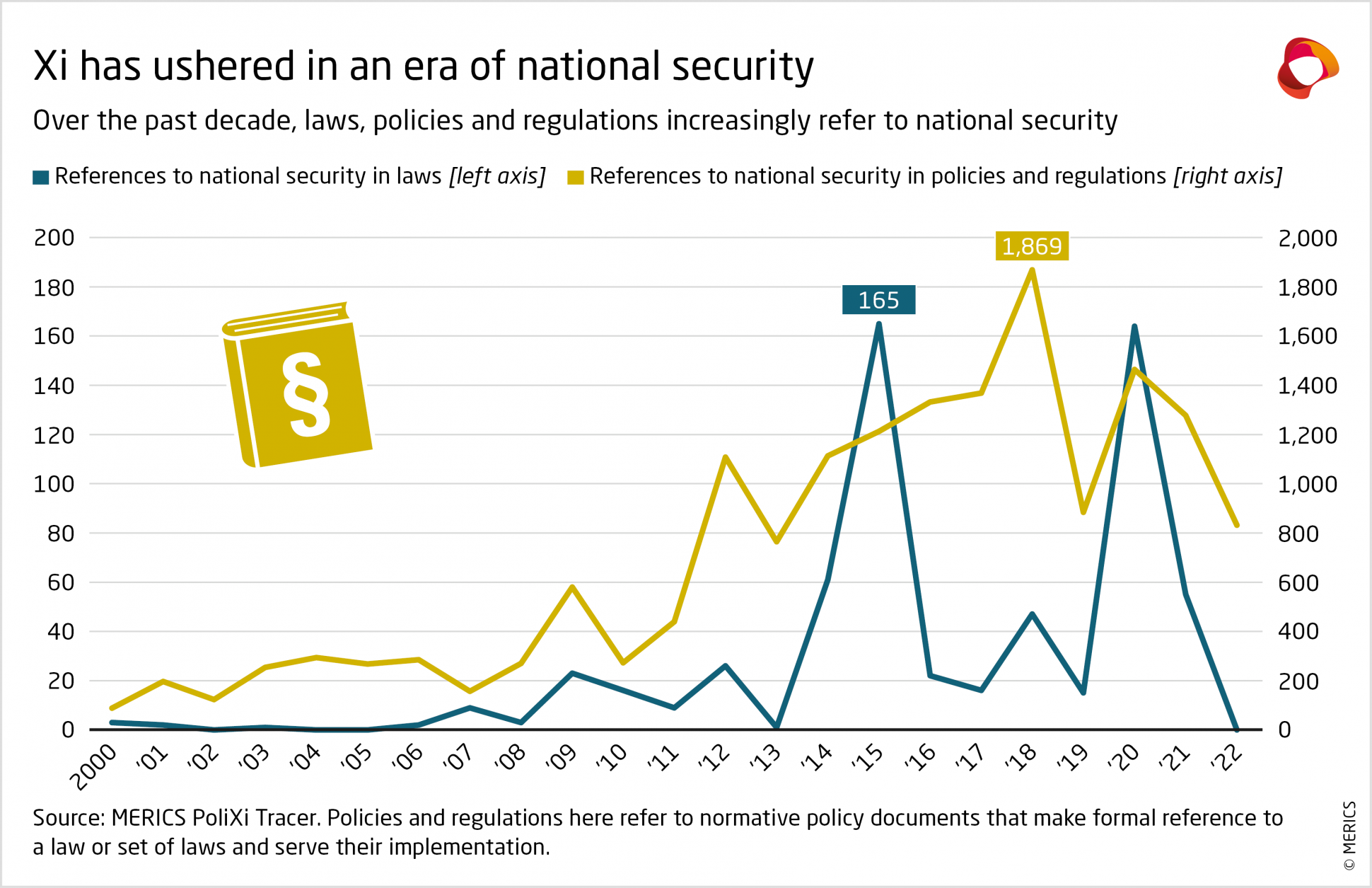

Xi’s push for centralization and institutionalization has been accompanied by a rapid expansion of the legal corpus, which state media refers to as a “legal Great Wall” to safeguard national security.19 Since 2014, a long list of national security-related laws has been issued, most notably the National Security Law (2015), the Counter-Terrorism Law (2015), the Counter-Espionage Law (2014), the Cyber Security Law (2016), the Foreign NGO Management Law (2016), the National Intelligence Law (2017) and the Data Security Law (2021). Upon instruction from Beijing, Hong Kong enacted its own all-encompassing National Security Law (HKNSL) in 2020.

These legal stipulations share a broad and ambiguous definition of national security. Several of these laws, notably the HKNSL and the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (2021), enable China to target behavior beyond its borders. Frequent references to national and public security not only filter down into policies and regulations (see Exhibit 3), but also into public and corporate guidelines and privacy statements.

All state and non-state actors are required to cooperate with authorities such as the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of State Security or military-affiliated intelligence forces, in cases relating to national security. China’s security organs have extensive discretionary powers to access data, with little or no transparency or legal recourse. By institutional design, the CCP has steering power over all security organs and the judiciary, whose work is coordinated under the national security commissions system. No independent bodies monitor their actions that citizens and enterprises could turn to if faced with undue requests for cooperation.

2.4 Mass mobilization and education: "everyone is responsible"

The party state is taking an all-of-society approach to safeguarding national security. The National Security Law states that “everyone is responsible for national security,” a decree echoed across laws, guidelines and public education campaigns – such as China’s annual “National Security Education Day” on April 15.20 All citizens, corporates and civil society are expected to proactively monitor and report potential security threats. A national security hotline was set up by China's Ministry of State Security in June 2022, offering up to CNY 100,000 for information.21

The concept of “comprehensive national security” is firmly embedded in political and public communication, education and scholarly discourse. It is set to influence the future thinking of decision makers, thought leaders and the public. National security is now promoted as a cross-disciplinary field of study, with new specialized research centers, programs and funds. In 2021, for example, the Research Center for Comprehensive National Security was established at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), a prominent research institute linked to the Ministry of State Security (MSS). CICIR has also released a series of publications on the topic, and its president Yuan Peng has held multiple lectures and trainings for leading cadres at different government levels.22

To future-proof the party state against domestic resistance, the leadership places a strong focus on inoculating China’s next generation against harmful influences. A roadmap to integrate national security in curricula was released in 2020. It beefed up post-1989 patriotic education by establishing national security-related content as a gradable competency across different subject syllabi. From elementary school onwards, students should learn to place China’s interests above their own and to defend their country. University students should have fully internalized what comprehensive national security means to inspire self- motivated actions.23 The defensive reflexes this creates are already playing out in university campuses globally.

3. Arenas of change: When the national security state goes into overdrive

The current leadership sees a growing number of issues and policy areas through a national security prism. Increasingly, the party state takes any perceived domestic resistance, or any international action affecting China’s overseas interests and image, as infringing its bottom line. Anti-foreign rhetoric is proliferating. Multiple issues are now framed as attempts by external actors – primarily the United States or wider West – to subvert the CCP and hinder China’s return to its rightful place in the world.

In this securitized environment, seemingly minor actions or statements may trigger harsh reactions from China’s officials, businesses or even individuals, even without direct orders from Beijing. While other top-down policy initiatives have led to inertia in the system, the national security imperative has led to over-implementation as lower-ranking officials fear overlooking a potentially existential threat. The result is a state of hyper-vigilance, with wide-reaching effects.

3.1 The "security first" paradigm has reshaped state-society relations

Under Xi, the party state has gone into overdrive to contain and preempt networked resistance to the regime. This thinking was already encapsulated in the internal party “Document No. 9,” issued in 2013, which targeted universal values and Western-style civil society, press freedom, and separation of powers. Xi’s statements on ideological and cultural security focus predominantly on the need to guard against Western values, which might trigger color revolutions and destabilize China.24 Legislation now restricts international engagement of China’s civil society and has put international NGOs in China under supervision by public security agencies.

The CCP leadership is particularly wary of sources of shared identity outside the nation and the party, which might give rise to collective action. In recent years, the party state has initiated repeated crackdowns against groups bound by ethnicity, language, religion, or common causes, especially those with multiple such “indicators” of potential threats.

Harsh repression in Xinjiang is the prime example, as Uyghurs and other minorities there share distinct languages, culture, faith, and have called for more autonomy in the past. Triggered by three terrorist attacks in the early years of Xi’s tenure, large segments of the region’s minority population have been affected by arbitrary detention, digital and physical surveillance, and forced cultural assimilation since 2016.25

The same logic is visible in repeated crackdowns and arrests of activists and advocacy groups working on issues as varied as labor, consumer, or LGBTQI+ rights. Nationalist anti- foreign sentiment provides a vehicle to delegitimize unwelcome causes: from calls to “lie flat” and refuse China’s hyper-competitive society, to the Hong Kong protests and feminist activism. What has emerged is a reflexive effort to designate many phenomena as Western plots to destabilize China.

Beijing sees individual identification with the party and country as fundamental to long- term security. Recent campaigns have focused on promoting a unified national identity (国家认同) and “correct” mainstream values. Xi has called for a comprehensive national security outlook in religious affairs to ensure that religious organs promote CCP core values and policies. Minority languages have been marginalized in public education and partly restricted from use online. All Chinese are meant to be “one heart and soul” under the banner of a Chinese nation (中华民族) and the leadership of the CCP.26 Those who resist may be subject to re-education – a potentially necessary step to clean Taiwan of “extremists and separatists” after reunification according to a PRC diplomat.27

Fear of networked resistance has also driven the expansion of China’s surveillance state. To establish a “peaceful China” (平安中国), the government seeks to create smart- and safe- cities and communities. This includes concerted efforts to leverage new digital technologies to monitor target groups and pre-emptively detect risks to public order and the party. As part of the so-called grid management system (网格化管理), grassroots party personnel are made responsible for a designated number of individuals, to monitor threats and mitigate issues where possible.28 These “boots on the ground” have been at the frontline of the party’s Covid response – even if current outbreaks in 2022 test their limits.

Building on the Great Firewall and other internet controls advanced by Hu Jintao, the current leadership has also invested heavily in controlling online spaces. The ramped-up capabilities were on display early in the pandemic when the death of whistle-blower Dr. Li Wenliang sparked mass calls for free speech, and later again during criticism of harsh pandemic policies. Whereas in the early 2010s, public incidents and scandals were often followed by weeks of critical discussion, now online spaces are quickly censored and flooded by messages supportive of the party within hours.

3.2 The quest for security has redefined China’s economic growth model

Economic development has been a key source of domestic legitimacy for the CCP and the basis of China’s growing international clout. From Deng to Hu, leaders clearly prioritized development. But Xi has changed the calculus. The new mantra is “integration of development and security” (统筹发展和安全), as endorsed in policy documents since late 2019 and in the current 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–25).29 In theory this signals equality; in reality it favors security.

Against the backdrop of Sino-US trade frictions and Western investment and market restrictions, including against Chinese telecommunication companies, Beijing has become more assertive in controlling its champions at home and defending them abroad. The shifting mindset is also visible in Xi’s 2020 overarching policy agenda of “dual circulation.” Its aims are to safeguard economic security by improving China’s socialist market economy while profiting from the benefits of globalization wherever possible.

The leadership is well-aware that China is entering an era of slower economic growth and seeks to ensure China’s technological self-sufficiency and increase the party state’s steering capacity over the economy. Since 2020, government organs have carried out waves of private sector regulation to discipline companies, align their actions with party priorities, strengthen party influence and prevent the formation of power bases outside the CCP.

The leadership seeks to channel resources and innovation based on national security priorities, given the links between economic, technological, cyber- and military security. Civil-military fusion efforts are prominent in Beijing’s plans to leverage emerging technologies to “leapfrog” the United States, its main strategic competitor. Informatization and innovation are pushed forward through top-down policy plans.30 Within these efforts, data is both a central “factor of production” and vital to political control. Laws and policies on cyber-, data- and information-security aim to ensure important data and IP is stored locally, accessible to China’s security watchdogs and protected from unwanted foreign insights.

But safeguarding stability and self-sufficiency – be it food, resource, financial or technological security – is easier said than done. Challenges in 2022 have ranged from the economic fallout of zero-Covid policies and extreme weather, to real estate slowdowns and local financial risks – with considerable implications for employment and people’s livelihoods.

This explains why reorienting global engagement and opening new markets – supported by Xi’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – has been high on the policy agenda. After US sanctions, securing China’s supply chains became a top priority.31 From semiconductors to rare earth and soy imports, China, too, is pursuing diversification and new economic ties with developing countries.

For private companies, national security looms everywhere in this new era. Bureaucracies are required to consider national security at every layer of decision-making. Consent can be withdrawn after initial clearance of business activities. Foreign companies face additional risks, as Beijing is expanding its retaliatory toolkit to protect China’s ever widening core interests. Multiple laws and regulations now have explicit clauses allowing “reciprocal measures” when state and corporate actions endanger China’s “sovereignty, security or development interests.”32

China’s government is also increasingly using “informal” economic coercion to safeguard its red lines, such as in the case of its sustained economic pressure campaign against Lithuania after they allowed a Taiwan Representative Office in the country. Other methods include state-amplified boycott campaigns against individual companies – such as H&M over statements on sourcing from Xinjiang.33

3.3 The securitization of policymaking fuels greater assertiveness abroad

As the world “undergoes changes unseen in a century”, the party state has stepped up efforts to shape the international environment. Securing China’s interests overseas and its position in the world has become a key objective of China’s national security work. China’s national security state once largely remained within China’s borders, but now is expanding internationally. China’s military build-up and modernization, its more assertive foreign policy, and efforts to control China-related narratives and policies internationally are meant to help Beijing achieve these goals. As almost everything has become a matter of national security, a wide range of behaviors now warrant a tougher response, regardless of its impact on bilateral ties or economic costs.

Multiple recent events have raised Beijing’s threat perceptions; from the emergence of a US-led coalition to confront China in the Indo-Pacific to the West’s united response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The CCP’s self-styled image as a responsible global power is jeopardized by investigations into human rights violations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. Reports about the social and economic costs of Beijing’s zero-Covid policy undermine claims of systemic superiority.

These developments have led to a shift in focus. Beijing increasingly views international relations through the lens of geopolitical competition with the United States. To “win,” the CCP leadership’s favors a two-pronged approach – to weaken the global reach of liberal democracies, and expand China’s. It applies incentives to woo support, largely in the Global South, and tough actions toward Western countries in the name of national security. As a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said: “For our friends, we have fine wine. Jackals or wolves, we welcome with shotguns.”36

Beijing’s “friends” are courted through the BRI, and newer initiatives like the GDI or the GSI, the latter a clear attempt to secure buy-in for Beijing’s state-centered approach to security. China is neither willing nor able to replace the US as a global security provider, but Beijing’s ability to promote its policy approaches by leveraging its economic weight and global dissatisfaction with the West should not be underestimated. It has succeeded in exporting its concept of the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and in shoring up support at the UN for its Xinjiang policies.

Western countries tend to be the main targets of forceful actions to enforce China’s red lines and interests, reflected in the shifting tone of China’s “wolf warrior” diplomats. The growing willingness to forcefully control narratives and behavior abroad was evident in the disproportionate sanctions on European individuals and entities in March 2021, in reaction to targeted EU sanctions for human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Beijing’s response to Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022 is another case in point. China’s aggressive warnings proved counterproductive in deterring the visit; the ensuing cancelation of dialogues with the US on topics ranging from defense to climate change severely limited remaining cooperation on urgent global issues.37

Despite their reputational and occasional economic impact, these apparent overreactions are likely to remain par for the course in China’s international relations. A new retaliatory toolkit to support the extraterritorial application of Chinese laws is being drawn up. In March 2022, Li Zhanshu, chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), said one of the year’s legislative priorities would be a “more complete system of laws and regulations related to foreign affairs” to “safeguard national security.”38

4. China’s approach differs from other countries — and comes at a cost

China is far from alone in the securitization of multiple policy fields. The trend has been evident in the United States and Europe too, especially since terrorist attacks in the early 2000s. Furthermore, it encompasses new policy fields – from climate to emerging technologies, supply chains and demographics. Public international law permits divergence from treaties under national and public security exceptions, whether trade agreements, WTO standards or human rights treaties. But China’s approach threatens to make the exception the rule – with significant internal and external implications.

4.1 What sets China’s approach apart

At first glance, the expansion of China’s national security concept seems to fit within global trends. But where constitutional and public oversight have repeatedly set boundaries or triggered course corrections for recent US and European expansions of national security, China’s rapid securitization across policy fields highlights a number of key differences in approaches:

- China’s view of national security is firmly integrated into party ideology. Safeguarding the CCP is a core component, hence the emphasis on containing domestic dissent and international criticism.

- China uses a broad and highly ambiguous definition of national security, often conflated with broader national and development interests. Mobilization efforts put officials and citizens in a state of eternal defensiveness and have a strong anti-foreign tone.

- China’s security organs have a wide remit and substantial resources, transforming China into a security state. State and non-state actors lack meaningful legal recourse to deny cooperation or challenge actions against them. There have been no constitutional limitations or institutionalized oversight.

- Beijing is increasingly codifying state powers and has shown a willingness to disregard international treaties and domestic legislation in the name of national security, especially in the field of human rights.

4.2 China’s pursuit of absolute security sparks internal criticism

There are costs to the party’s increasing focus on national security above all else. Especially in the international arena, it often gives rise to conflicting goals and has impeded cooperation beneficial to China’s development interests. While Xi Jinping calls for a more “lovable China” that is internationally respected, its harsher language, rights abuses and economic coercion have prompted a re-evaluation of the relationship in Europe. Wide-reaching national security legislation has also raised significant distrust in Chinese technology and communications companies.

The current course has drawn criticism from prominent voices inside China, though so far only from outside the government. Zhang Baijia, a former deputy director of the Party History Research Centre has said “if we magnify national security too much, it will be practically impossible for us to remain open to the outside world.”39 In a recent article, Jia Qingguo, former dean of Peking University’s School of International Studies and leading international relations expert, warned that China should follow a “principle of moderation,” as the quest for absolute security will damage China’s ability to pursue broader interests and values.40

Some of the longer-term dangers of Beijing’s current course have also been outlined by Tsinghua University professor Yan Xuetong. He fears the next generation of citizens and decision-makers is likely to be overconfident and stuck in a make-believe mindset about China’s ability to achieve its foreign policy goals, raising the risk of misguided policy choices. An overconfident Generation Z in China, he argued, thinks that “only China is just and innocent, while other countries, especially Western countries, are evil.”41

5. Conclusion: European actors need to develop responses to China's "securitization of everything"

Under Xi, the comprehensive national security concept has turned into a guiding principle of policymaking. It is seen as a “powerful ideological weapon” (强大思想武器) under constant development to respond to new threats, real or perceived.42

The party state’s current behavior is not a temporary tightening, nor a bug in the system, as can be seen from the long evolution of national security work. The “securitization of everything” is here to stay and will likely accelerate. The CCP believes threats are at an all- time high and that China’s ability to maintain national security is still insufficient. Despite gaining confidence in China’s power and capabilities, it feels the need to be “prepared for the unexpected” (忧患意识) and “vigilant in peacetime” (居安思危).43

This all-encompassing national security mindset is increasingly locking China into certain modes of action. By priming officials and citizens alike to be on the constant lookout for potential new threats, and thus increasing the risks of overreactions and arbitrariness, pragmatism has given way to ideology. No amount of engagement or cajoling will lead to Beijing shifting away from this security-focused, illiberal trajectory, short of major internal rethinking and reforms.

Domestic criticism reveals, however, that this approach is not uncontested. Not everybody is an ardent defender of the concept, and many may want to maintain China’s room for action.

Party-state actors are still assessing the costs to China’s economic development and international standing. Foreign actors can seek to change the party’s calculations by communicating concerns and raising the costs for harmful behaviors through coordinated, targeted responses.

State and public sector actors in Europe

- Track the evolution of China’s national security framework and related policies. Seek input from companies, academia and civil society about specific impacts on engagement with China. This can help predict future areas of securitization, identify triggers for retaliation and prepare responses.

- A key pattern of Beijing’s behavior is making an example of smaller countries and actors to deter others. Avoid acquiescing to pressure tactics, especially where immediate harm seems low, as this incentivizes similar behavior. Build up resources and networks for mutual support to help resist China’s demands and mitigate economic losses.

- Ensure negative international impact registers in Beijing. Raise your dissatisfaction about specific actions, e.g., cases of disproportionate retaliation, with Chinese counterparts repeatedly and at the highest possible level. Be direct about the loss of trust and impact on longer term engagement. Whenever possible, speak out publicly.

- Communicate your country’s interests, principles and red lines clearly. Strengthen communication to global stakeholders and make clear where Europe’s values, practices and legal safeguards differ from Beijing’s illiberal approach to security.

Companies

- Understand that underlying parameters of doing business in China have changed and prepare strategies to deal with new uncertainties. Companies may face national security investigations, market restrictions, consumer boycotts, and fallout from broader economic coercion measures, even when they have been legally compliant in China.

- Undertake regular risk assessments of exposure to national security clauses and concerns. Risks differ across industries, depending on China’s level of self-reliance. Beijing’s focus and calculus may shift as China becomes more economically and technologically independent.

- Use official contacts and foreign business associations to tell Chinese counterparts how this approach affects your company or industry, repeatedly and at the highest possible level. Be direct about the degree of uncertainty and specific challenges this creates, and how this impacts long-term investment and business considerations.

- Build up networks between companies and develop strategies that will help you collectively voice concerns and resist China’s demands in case of conflict. Prepare for scenarios that allow you to quickly diversify your business and supply chain links.

Academia and civil society

- Be aware that China’s engagement in international research cooperation is also driven by security goals, such as technological leadership. Establish due diligence procedures to ensure research outcomes are equitably shared and do not inadvertently support China’s growing public security and military sector.

- Understand that how China is researched and discussed abroad has become a target for Chinese state criticism and action, including through online campaigns, denial of access and sanctions. Build up resources and networks for mutual support to track incidents, discuss response strategies, and prevent self-censorship.

- Some areas for exchange and cooperation, especially related to civil society, rights and independent academia and media have been irrevocably tightened. Work can and should be focused on engaging Chinese actors internationally to keep lines of communication open.

- Endnotes

-

1 | The concept was added to the amended CCP Constitution in 2017: 中国共产党章程 (2017). http://dang- jian.people.com.cn/GB/136058/427510/428086/428087/index.html. Accessed: August 25, 2022; for background also see: Greitens, Sheena (2021). “Internal Security & Grand Strategy: China’s Approach to National Security under Xi Jinping”. January 28. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-01/ Sheena_Chestnut_Greitens_Testimony.pdf. Accessed: August 26, 2022.

2 | Xinhua (2021a). “中共中央关于党的百年奋斗重大成就和历史经验的决 (Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Major Achievements and Historical Experiences of the Party's Centennial Struggle). November 16. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-11/16/content_5651269.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

3 | Xinhua (2021b). “CPC leadership reviews documents on national security strategy, military honors regulations, sci-tech advisory report”. November 18. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2021-11/18/ content_10108963.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

4 | Xinhua (2022). “Xi stresses safeguarding national security, social stability, peaceful lives”. January 15. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202201/15/WS61e26eeaa310cdd39bc81418.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022; Xinhua (2020). “贯彻总体国家安全观 习近平提出10点要求 (Implementation of the overall national security concept Xi Jinping put forward 10-point requirements)”. December 12. http://www. xinhuanet.com/politics/xxjxs/2020-12/12/c_1126853459.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

5 | Yuan, Li (2022). “Why China’s Confidence Could Turn Out to Be a Weakness”. August 9. https://www. nytimes.com/2022/08/09/business/china-xi-jinping-united-states-taiwan.html. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

6 | Kennedy, Scott (2021). “Beijing Suffers Major Loss from Its Hostage Diplomacy”. September 29. https:// www.csis.org/analysis/beijing-suffers-major-loss-its-hostage-diplomacy. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

7 | Xinhua (2014). “中央国家安全委员会第一次会议召开 习近平发表重要讲话 (The first meeting of the Central National Security Commission held Xi Jinping delivered an important speech)”. April 15. http://www. gov.cn/xinwen/2014-04/15/content_2659641.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022; China Overseas Chinese Network (2014). “中国国家安全工作即将进入全新发展阶段 (China's national security work is about to enter a whole new stage of development)”. April 17. http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2014/0417/c40531- 24909488.html. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

8 | Xi Jinping (2018). 习近平关于总体国家安全观论述摘编 (Excerpts from Xi Jinping's Discourse on the Overall National Security Concept). 中共中央党史和文献研究院 (eds.) 中央文献出版社; Xi Jinping (2022). 总体国家 安全观学习纲 (Overall national security concept study outline), April 15. https://item.jd.com/13136945. html. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

9 | Qiushi (2017). “中国国家安全理论与实践的重大创新 (A major innovation in China's national security theory and practice)”. February 28. http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2017-02/28/c_1120536834.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

10 | Renmin Ribao (2014). “习近平:坚持总体国家安全观 走中国特色国家安全道路 (Xi Jinping: Adhere to the overall national security concept to take the road of national security with Chinese characteristics)”. April 16. http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0416/c64094-24900492.html. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

11 | Renmin Ribao (2022a) „Global Development Initiative will respond to the needs of all countries”. March 31. https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/news/pressreleases/202203/t20220331_1321484.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022; The Economist (2022). “China’s Global Development Initiative is not as innocent as it sounds”. June 9. https://www.economist.com/china/2022/06/09/chinas-global-development-ini- tiative-is-not-as-innocent-as-it-sounds. Accessed: June 30, 2022; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2022). “Xi Jinping Delivers a Keynote Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2022”. April 21. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/ zxxx_662805/202204/t20220421_10671083.html. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

12 | Ling, Shengli and Fan Yang (2020). “新中国70年国家安全观的演变:认知、内涵与应对 (The Evolution of New China's National Security Concept in 70 Years: Perception, Connotation and Response)”. May 11. http://www.cssn.cn/gjgxx/gj_zgwj/202005/t20200511_5126816.shtml. Accessed: June 30, 2022; For more background see also: Yuan, Jingdong (2022). Chinese National Security: New Agendas and Emerging Challenges. In: Clarke, M. Heschke, A., Sussex, M. Legrand, T. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of National Security. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

13 | Buckley, Chris and Steven Lee Meyers (2022). “In Turbulent Times, Xi Builds a Security Fortress for China, and Himself”. August 6. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/06/world/asia/xi-jinping-china-se- curity.html. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

14 | State Council Information Office (2022). “台湾问题与新时代中国统一事业 (The Taiwan Question and China's Reunification in the New Era)”. August 10. www.gwytb.gov.cn/topone/202208/ t20220810_12459866.htm. Accessed: August 24, 2022.

15 | For more background information see: David M. Lampton (2015). Xi Jinping and the National Security Commission: policy coordination and political power, Journal of Contemporary China, 24:95, 759-777; Wuthnow, Joel (2022). “Transforming China’s National Security Architecture in the Xi Era”. January 27. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-01/Joel_Wuthnow_Testimony.pdf. Accessed: August 26, 2022; Julienne, Marc (2021). “Xi Jinping’s Conquest of China’s National Security Apparatus”. July 1. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/xi-jinpings-conquest-chinas-national-security-appara-tus-31007. Accessed: August 26, 2022.

16 | Deng, Xiaoping (1980). 目前的形势和任务 (The Present Situation and the Tasks Before Us). January 16. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/deng-xiaoping/1980/217.htm. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

17 | Qin, Liwen (2014). “Securing the “China Dream”: What Xi Jinping wants to achieve with the National Security Commission (NSC)”. February 28. MERICS. https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/China%20Monitor%20No_4.pdf. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

18 | Mitchell, Tom (2022). “Xi Jinping grasps ‘knife’ of internal security to complete grip on power”. August 9. https://www.ft.com/content/cff2160d-a279-4562-ba43-3d56ba99f06d. Accessed: August 25, 2022. 19 | Li, Yan (2022). “China builds legal Great Wall to safeguard national security: official”. April 25. http://www.ecns.cn/news/2022-04-25/detail-ihaxrxye1107670.shtml. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

20 | Buckley, Chris and Steven Lee Meyers (2022).

21 | Xinhua (2022). “国家安全部公布部门规章《公民举报危害国家安全行为奖励办法》 (Ministry of State Se- curity announced departmental regulations ‘citizens to report acts of endangering national security incentives’)”. June 7. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-06/07/content_5694451.htm. Accessed: June 30. 2022; Global Times (2022). “China's top security authority institutionalizes rewarding citizens for reporting activities that endanger national security”. June 8. https://www.globaltimes.cn/ page/202206/1267544.shtml. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

22 | Sinocism has documented and translated excerpts of numerous speeches and reports related to Peng Yuan’s activities, and national security policies and training efforts more broadly, which can be found at https://sinocism.com/archive?triedSigningIn=true&sort=search&search=national%20security.

23 | Ministry of Education教育部 (2020). 大中小学国家安全教育指导纲要, 教材5号 (Schools and Universities National Security Education Guideline, Document Nr. 5). October 20. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/ A26/s8001/202010/t20201027_496805.html. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

24 | Xi (2018); Johnson, Matthew D. (2020). “Safeguarding socialism: The origins, evolution and expansion of China’s total security paradigm”. June 11. https://sinopsis.cz/en/johnson-safeguarding-socialism/. Accessed: August 25, 2022; Blanchette, Jude (2020). “Ideological Security as National Security”. De- cember 2. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/ideological-security-national-security. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

25 | Greitens, Sheena Chestnut, Myunghee Lee and Emir Yazici (2020). Counterterrorism and Preventive Repression: China’s Changing Strategy in Xinjiang. International Security 2020, 44 (3): 9–47.

26 | Millward, James A. (2022). “(Identity) Politics in Command: Xi Jinping’s July Visit to Xinjiang”. August 16. The China Story. https://www.thechinastory.org/identity-politics-in-command-xi-jinpings-july-vis- it-to-xinjiang/. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

27 | Carbonaro, Giulia (2022). “China Would Re-Educate Taiwan in Event of Reunification, Ambassador Says”. August 5. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/china-reeducate-taiwan-reunification-am- bassador-1731141. Accessed: August 29, 2022. For a full video of Ambassador Lu Shaye’s remarks see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odJA2apdn5I

28 | Pei, Minxin (2021). “Grid Management: China’s Latest Institutional Tool of Social Control”. March 1. China Leadership Monitor. https://www.prcleader.org/pei-grid-management. Accessed: August 29, 2022.

29 | Howard Wang (2022). ‘Security Is a Prerequisite for Development’: Consensus-Building toward a New Top Priority in the Chinese Communist Party, Journal of Contemporary China; Xinhua (2021c). “中华 人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和2035年远景目标纲要 (Outline of the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China and the Vision 2035). March 13. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm. Accessed: August 26, 2022.

30 | Cheung, Tai Ming (2022). Innovate to Dominate, The Rise of the Chinese Techno-Security State. Cornell University Press.

31 | Toshiya, Tsugami (2022) “Three Things to Know About China’s “Economic Security”. March 7. https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/a07902/. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

32 | Drinhausen, Katja and Helena Legarda (2021). “China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: A warning to the world”. June 24. MERICS. https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/chinas-anti-foreign-sanctions-law-warn- ing-world. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

33 | Adachi, Aya, Alexander Brown and Max J. Zenglein (2022). “Fasten your seatbelts: How to manage China’s economic coercion” August 25. MERICS. https://merics.org/en/report/fasten-your-seat- belts-how-manage-chinas-economic-coercion. Accessed: August 25, 2022.

34 | Bloomberg News (2021). “China Tech Rout Deepens to $1.5 Trillion as Didi Emboldens Bears”. Decem- ber 3. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-03/china-tech-rout-deepens-to-1-5-trillion-as-didi-emboldens-bears. Accessed: August 29, 2022.

35 | Chen, Lulu Yilun and John Cheng (2022). “China State-Owned Giants to Delist From US Amid Audit Spat”. August 12. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-12/china-state-owned-gi- ants-plan-to-delist-from-us-amid-audit-spat. Accessed: August 26, 2022; Chen, Stella and David Bandurski (2022). „CNKI’s Security Problem”. July 6. China Media Project. https://chinamediaproject. org/2022/07/06/cnkis-security-problem/. Accessed: August 26, 2022.

36 | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2022). “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin’s Regular Press Conference on May 24, 2022”. May 24. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_ eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/202205/t20220524_10692075.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

37 | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2022). “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Announces Countermeasures in Response to Nancy Pelosi’s Visit to Taiwan”. August 5. https://www. fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202208/t20220805_10735706.html. Accessed: August 24, 2022.

38 | Renmin Ribao (2022b). “China to further develop laws related to foreign affairs”. March 8. http://www. chinadaily.com.cn/m/supremepeoplescourt/2022-03/08/content_37550172.htm. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

39 | Buddhavarapu, Ravi Shankar (2021). “Signs of dissent against Xi in China over zealous challenge to the US”. December 24. https://www.news9live.com/opinion-blogs/signs-of-dissent-against-xi-in-china- over-zealous-challenge-to-the-us-142594. Accessed: June 30. 2022.

40 | Jia, Qingguo (2021). “对国家安全的特点和治理原则之思考 (Reflections on the characteristics of national security and principles of governance)”. December 29. http://www.aisixiang.com/data/130598.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

41 | Mai, Jun (2022). “China’s Gen Z overconfident and thinks West is ‘evil’, top academic says”. January 14. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3163476/ chinas-gen-z-overconfident-and-thinks-west-evil-top-academic. Accessed: June 30, 2022; see also thread and older analysis on Yan by Wang Zicheng from 12 January 2022: https://web.archive.org/ web/20220112164339/https://twitter.com/ZichenWanghere/status/1481304603706617859. Ac- cessed: June 2022.

42 | Renmin Ribao (2020). “深刻理解和把握总体国家安全观 (Deeply understand and grasp the overall national security concept)”. April 14. http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0415/c40531-31673757.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022.

43 | Peng, Yuan (2022). “以高水平安全保障高质量发展 (High level of security to ensure high-quality develop- ment)”. May 1. http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0105/c40531-32324058.html. Accessed: June 30, 2022.