E-government and Covid-19: Digital China goes global

In this MERICS Primer, Rebecca Arcesati explores how China is exporting its vision for digital transformation and e-governance to the world, in particular to the Global South. The analysis is accompanied by a slidedeck that provides context for and deeper insights on the topic.

Digital transformation is a top priority of the PRC’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP). Having built a solid foundation for its digital economy, Beijing wants to reach the next phase: integrate digital technologies with the real economy, society and government functions to drive economic upgrading and modernize the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s governance capabilities. This was one of the messages that China’s President Xi Jinping delivered during a Politburo study session last October. It took place amidst an unprecedented regulatory campaign through which the state is trying to steer the consumer tech sector in service of national goals.

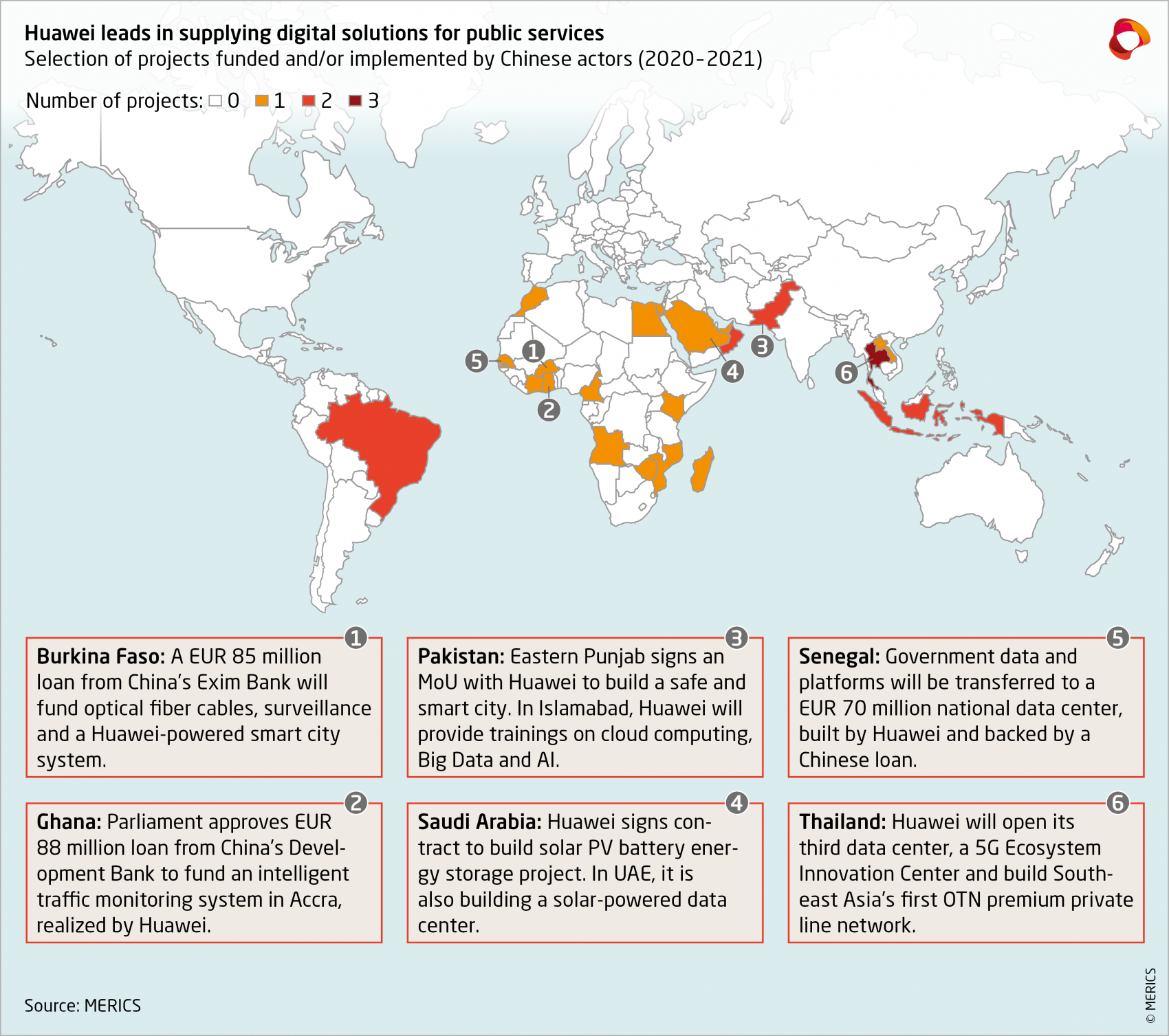

Beijing’s vision does not stop at home: it is global and builds on a decades-long strategic approach toward Internet infrastructure in the Global South. Blending diplomacy, industrial policy and state credit, China’ government has sustained Chinese telecommunications firms’ race to market dominance. In Africa, it was estimated that Huawei built roughly 70 percent of 4G networks. Through a partnership plan it proposed in August 2021, China now seeks to deepen its ICT engagement with African partners and reap the benefits of the continent’s digital revolution, spanning industrial applications of emerging technologies, regulatory cooperation, and the digitalization of public services like transport and healthcare.

As the European Union readies to mobilize EUR 300 billion to compete with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) through its Global Gateway, China has already moved beyond building backbone infrastructure. A case in point is the digitalization of public administrations and public services (e-government), which has accelerated since the Covid-19 outbreak as more government activities are being pushed online. Party-state-linked firms like Huawei are making inroads into this area, while Beijing increasingly promotes cooperation on digital government – and governance – with developing and emerging economies. Aside from a force for development and public welfare, e-government has become a terrain of competition around political values.

Chinese leaders think every aspect of governance must become digital

The Covid-19 crisis has allowed China to test its already extensive digital monitoring and smart city infrastructure, while spurring growth and innovation in industries from robotics to Artificial Intelligence (AI). The government embraced digital technologies in the fight against the virus, enlisting the private tech industry to supply data-driven solutions. These range from movement-tracing apps, facial recognition, and thermal imaging systems to AI- and big data-driven platforms and models for communication, disease prediction and resource management in the healthcare sector.

Given the success of the campaign, Beijing feels vindicated in its commitment to tech-driven governance. Between 2018 and 2020, China's ranking on the United Nation’s E-Government Development Index (EGDI) increased by 20 spots to 45th globally. Part of the effort to build a “Digital China” (数字中国), the FYP outlines, shall focus on deepening the construction of a digital society where public services, cities, villages, and communities become “smart” (智慧), and government operations, information management and services more efficient, data-driven, and integrated.

The concept of “smart governance” (智治), a key tenet of Xi Jinping’s vision for ruling the country, does not merely entail making services like healthcare or education more convenient and cities more livable: the party sees digital technologies as the secret sauce to rule the country in a “scientific” way by preventing any emergency, from public health hazards to political and social risks, from endangering the party’s hold on power. Chinese smart cities are conceived as integrated platforms that should help local officials, simultaneously, surveil society and improve the provision of public services.

Covid-19 opened new opportunities to export Chinese smart city technologies

The pandemic further bolstered China’s campaign to export its smart city technologies, as global demand for digital tools and services surged. Companies that supplied drones, thermal cameras for temperature screening, contact tracing systems and other products to local governments across China were well-positioned to assist other countries with “epidemic prevention and control” (疫情防控).

Video surveillance equipment firms are a case in point. Hikvision, Dahua and Uniview supplied cameras that detect people with a fever or not wearing a mask. They had 65 Covid-19-related global points of presence as of June 2021, according to figures compiled by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Huawei, a leading global provider of smart city and public security platforms, was very active, focusing on cloud services – mostly teleconferencing platforms – for online education and healthcare-sector communication. Through this outreach, the company further strengthened its ties with governments seeking to digitalize public services. In Kenya, the health ministry appears to have chosen Huawei to implement its telemedicine initiative.

These developments could bring long-lasting effects on global technology markets way beyond the health crisis. Although Western countries are growing wary of Chinese smart city technologies due to data security and human rights concerns, vendors like Huawei remain attractive to developing and emerging economies worldwide.

China’s government seeks to leverage companies’ global expansion. In May 2017, Xi Jinping said that cooperation with BRI countries on “smart city construction” (智慧城市建设) should be fostered as part of building a Digital Silk Road (数字丝绸之路). The party-state supports many projects, most tangibly through financing, to align them with its goals. For example, one objective is to influence international technical standards for smart cities.

Already before Covid-19, the Digital Silk Road posed a dilemma for many developing nations: while Chinese technology brought connectivity and promised development, the United States and its allies warned them about the underlying risks.

The promise and peril of Chinese e-government technologies

Chinese firms have attracted most attention for their role in exporting surveillance technologies, but policing is far from the only government service that they are supporting. China’s new white paper on China-Africa cooperation states that 29 African countries use Chinese smart government services.

While e-government and the use of ICT for delivering public services like healthcare and education can play a fundamental role in closing the digital divide, beneficial technologies often come with hidden risks and costs. Chinese surveillance giants who purport to keep people safe from Covid-19 have repurposed the same technologies the Chinese police use to persecute Muslim minorities. The temperature screening solution of deep learning company Megvii, which was hit by new US government sanctions in December over its complicity in the surveillance of Muslims in Xinjiang, experienced international success. These technologies were developed in an environment where the recipe for public health security is constant and unconstrained surveillance, a troubling model that the party-state has touted as an example for other countries to learn from.

Government information platforms

More and more governments are relying on Chinese infrastructure to power the critical infrastructure on which data-intensive public services rely. Based on Huawei’s e-government cloud, Cape Verde’s Operational Nucleus for the Information Society “developed more than 150 websites and 77 types of eGovernment software, covering social security, electronic elections, budget management, distance education and healthcare, and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) for all government departments, schools, hospitals, and state-owned enterprises.” The Export Import Bank of China backed the project with several loans.

Such a deep penetration into government networks potentially provides the Chinese state with channels for intelligence collection and political influence. Coupled with a track record of lax cybersecurity practices, recent regulatory developments in China further increase the risks: for example, new rules for software vulnerabilities oblige Chinese ICT vendors to report bug details to state authorities without disclosing them to overseas entities.

Smart education

China is among the most ambitious countries in the world in digital education, especially in its efforts to modernize teaching and learning through emerging technologies like AI. In 2019, China spearheaded UNESCO’s Beijing Consensus on Artificial Intelligence in Education. During the pandemic, it launched two distance learning platforms with UNESCO while experts from several Chinese universities and tech firms compiled a technical guide on protecting personal data security in e-learning. Considering the crucial role of education in cementing the CCP’s authoritarian rule at home, Chinese state actors’ involvement in setting international norms in this field raises serious political questions.

Furthermore, some of the companies that are implementing smart education projects overseas have deep ties with the Chinese police and supply technologies that enable the repression of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. IflyTek, China’s national champion for voice-related AI, has supplied voiceprint recognition systems to public security authorities in the region. It also claims to provide multilingual translation services in 55 BRI countries and cooperates with UNESCO on building smart classrooms. These projects could grant IflyTek access to vast troves of data it can use to train its algorithms.

Sharing China’s digital governance wisdom: Beijing steps up digital economy cooperation

As the European Union Institute for Security Studies noted, China-sponsored trainings to developing countries on “smart society and smart city construction” reveal Beijing’s ambition to promote its approach to governance by digital means. Researchers affiliated with the National Development and Reform Commission’s State Information Center, which coordinates China’s e-government network, recommend the Chinese smart city “concept” be spread overseas.

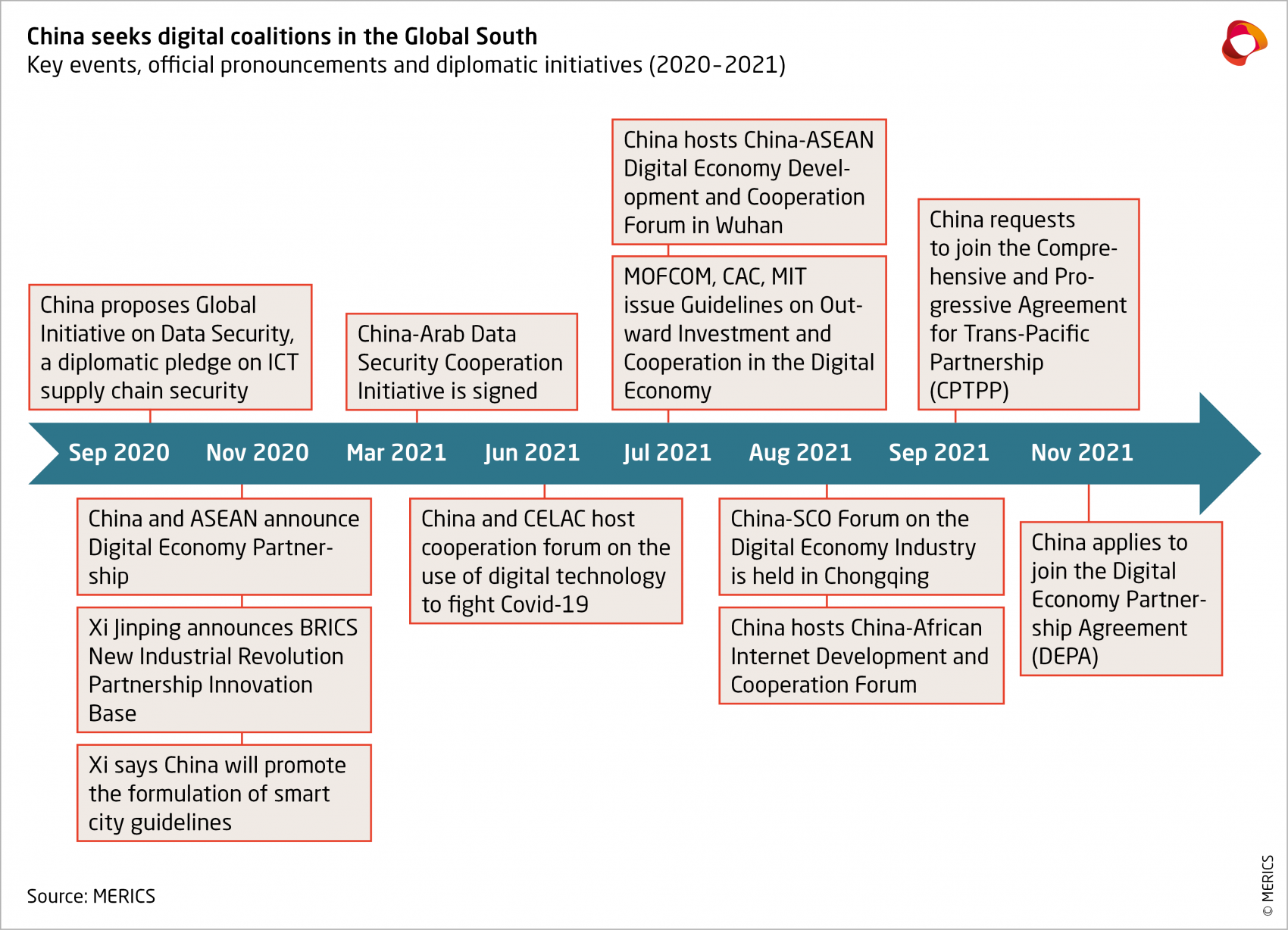

Indeed, China seems to think its approach to digital government and governance can inspire others. At the 2020 World Internet Conference, the head of the Cyberspace Administration of China, Zhang Rongwen, stated that “China has actively used frontier technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence in resource allocation and epidemic prevention" and “has shared such experience without reservation with other countries.” Deepening “cooperation in the digital economy” (数字经济合作) was a recurrent theme in China’s diplomacy throughout 2020 and 2021.

Following geopolitical tensions with the United States and other advanced economies, and the resulting trade and investment restrictions on its national ICT champions, the economic and diplomatic imperatives for Beijing to build coalitions with developing and emerging countries are stronger than ever. Coming in as regulators were drafting sweeping laws on data security and personal information protection, the Global Data Security Initiative also embodies China’s desire to assert its data governance narrative and position itself as a global standard setter in governing the digital space.

The strategic reasons behind delivering digital public goods

From Beijing’s viewpoint, China’s domestic experience positions it well to support e-government and digital development in the Global South. A multi-ministry policy document issued in July 2021 encourages cooperation with BRI countries in areas such as e-government and telemedicine, and invites companies to digitize traditional infrastructure in host countries. The digital economy is one of the pillars of Xi Jinping’s strategy for international cooperation in cyberspace, where the narrative centers on closing the digital divide in the Global South. For the first time, in January 2021, China’s third white paper on foreign aid mentioned projects related to the digital economy among the sectoral priorities.

Delivering digital “public goods”, as Chinese cybersecurity scholar Wang Xiaofeng put it, is part of a recalibration of the BRI away from controversial and costlier transport and energy projects and toward “high-quality development” (高质量发展). As Jon Hillman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies observed, much of global bandwidth growth in coming years will take place in developing and emerging economies; controlling tomorrow’s most vibrant technology markets fits the economic strategy of “dual circulation” (国内国际双循环).

Several Chinese experts believe that the pandemic has added momentum to the construction of the Digital Silk Road. For Zhai Kun at Peking University, China should respond to Washington’s “digital hegemony through digital aid” in the Indo-Pacific by spearheading a new digital governance model with ASEAN, bringing in the EU. The Digital Silk Road provides an opportunity for the Global South to develop “a new framework for digital governance rules,” observed Zhang Monan from the China Center for International Economic Exchanges.

Implications for the EU’s Global Gateway

A healthy degree of competition between the EU’s Global Gateway and China’s Digital Silk Road could bring tangible results for development, helping to close the global digital infrastructure gap. China often provides much-needed technological and financial assistance in support of development. And some of the projects that Chinese firms are implementing tie with European objectives: green data centers, for example, could help mitigate the environmental footprint of digital infrastructure.

At the same time, China’s provision of technologies and capacity for the digitalization of governance and public services situates it as a “systemic rival” along the EU’s strategic spectrum for dealing with the relationship. Whereas Europe aims to tackle the digital divide through secure connections, Chinese projects expose recipient countries to considerable data protection risks, while bringing business opportunities to firms with a track record of complicity in human rights violations.

Crucially, Beijing is eager to promote its approach to governance by digital means, which has proven effective during the Covid-19 pandemic. While Brussels aims to do something similar with its digital economy packages, the difference is that China’s approach to smart governance puts the state’s interests before those of its citizens. The outcome of this normative competition will likely vary country by country, depending on the degree to which Chinese and European projects succeed at meeting local needs. China will surely invest growing financial and political capital because it wants to prevail.