When giving birth is a national duty: Beijing’s struggle to reverse demographic decline

Key findings

- The Chinese leadership faces unique challenges to sustainable population growth. The legacy of the One-Child Policy is proving difficult to reverse, and stubborn systemic factors are equally hard to address, including the rising costs of raising children and workplace discrimination against women of childbearing age.

- Beijing has shifted its goal from containing population growth to boosting it. China’s shrinking population poses a threat to economic growth and its ambitions to be a global superpower, so the authorities are trying to raise the birth rate. The repercussions of Beijing’s demographic successes and failures will reverberate across the world.

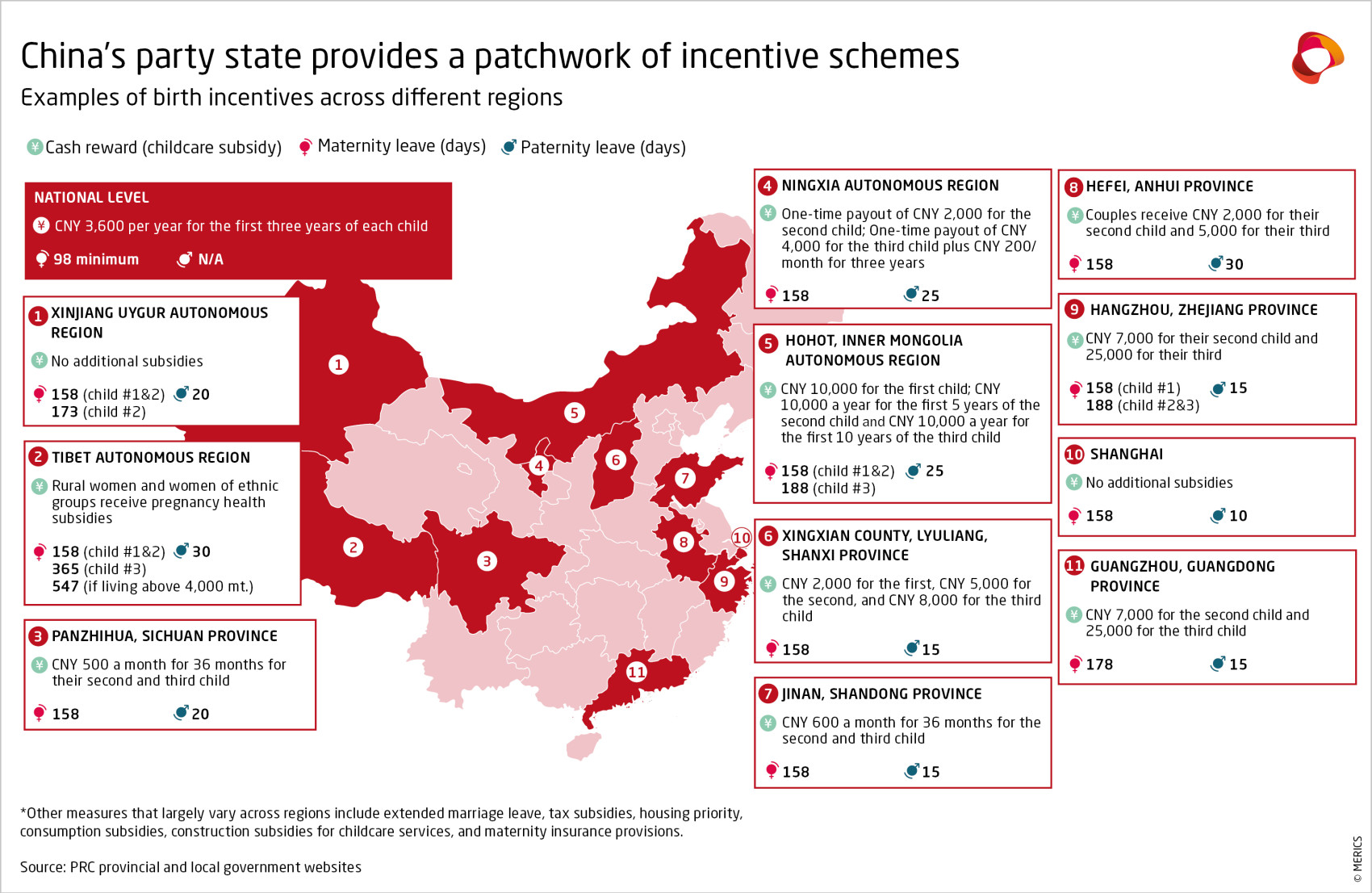

- Central and local governments have rolled out a patchwork of incentives, with uneven outcomes. The most recent is China’s first nationwide child subsidy of CNY 3,600 (EUR 430) per child per year, until age three. Substantial investment is still lacking.

- Many citizens remain skeptical of government efforts. The mismatch between people’s desires (often to remain single, or to have small families) and government interventions is likely to deepen social discontent.

- Population pressures have been elevated to a national security issue, trumping women’s freedom of choice and bodily autonomy. Online discussions show signs of resistance from women and other parts of the population who have been openly critical of the shift.

- Some regions have introduced coercive policies. New pro-natalist policies and campaigns frame women primarily as mothers and caregivers, eroding gender equality gains. These steps raise concerns about women’s rights.

Introduction: China’s demographic challenges

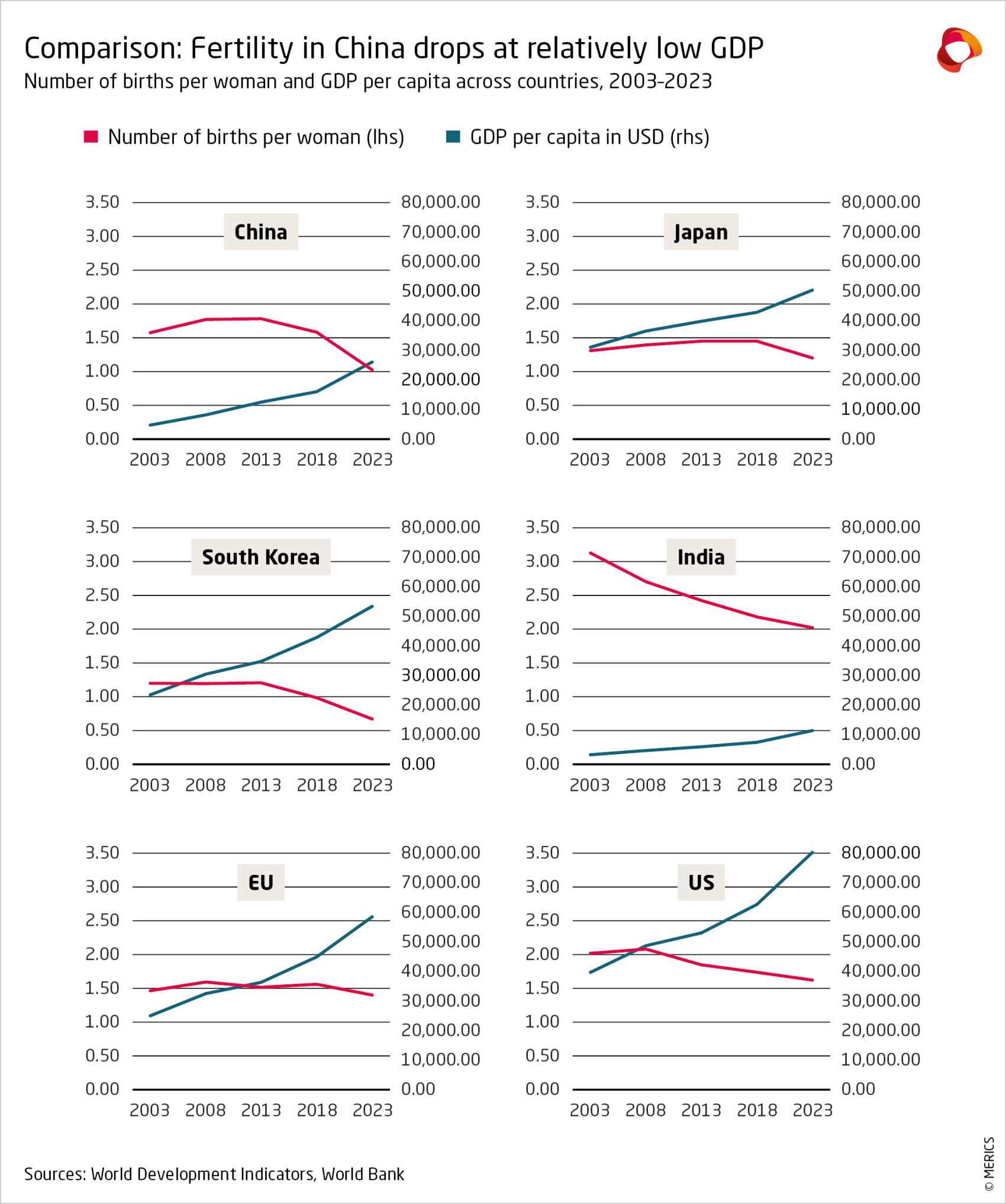

China's demographic dilemma is characterized by a rapidly aging population, a declining birth rate, and a shrinking workforce. Many other countries share population challenges (see exhibit 1), but China's problems have unique characteristics, foreshadowing a crisis that is unprecedented in many of its aspects.

As of 2022, China’s fertility rate dropped to an estimated 1.09 births per woman, far below the replacement level of 2.1, and similar to Japan’s or South Korea’s.1 However, China’s GDP per capita of around USD 23,000 is still much lower than in these two relatively high-income countries. Most developed nations had reached higher GDP levels before experiencing fast population decline. The fear is that China will grow old before it grows rich, especially if over time economic growth continues to slow.

China’s population has been contracting since 2022, with the number of people aged 65 and over surpassing 15.4 percent, meeting the UN’ classification of an “aged society.”2 Meanwhile, the working-age population (15–59) fell from 69.2 percent in 2012 to 62.6 percent in 2023.3 A declining population will eventually result in labor shortages, reduced productivity, and increased fiscal pressure from pension and healthcare obligations. These factors could erode the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) long-term plans for modernization and China’s economic growth trajectory.

The authorities are now trying to reverse this population trend. Given the warnings from Chinese demographers since at least the early 2000s,4 the current policy shift is only surprising for its late timing. The alarming long-term prospects have finally got the attention of leaders in Beijing; from a top-level policy perspective, changes need to happen soon – a fact mirrored by the flurry of recent activity to promote childbirth.

Developments since the beginning of liberalization of the One-Child Policy suggest that it will be extremely difficult for policymakers and local governments to achieve the results they hope for, and recent efforts are likely too little too late. The effectiveness of China’s pro-natalist policies will carry far-reaching consequences, not only for its economic trajectory, but also for China’s military strength, technological progress and global prosperity, which rely on sustained Chinese growth.

Re-engineering the one-child generation

“Tell the Chinese story of beautiful love, harmonious family, and happy life in the new era” (Party Committee of the National Health Commission)5

The internal obstacles towards sustainable population growth confronting Chinese policymakers are extremely intricate. To ensure China’s long-term prosperity, the party leadership now has to reverse a deeply politically and socially sensitive policy of its own making. Decades of the One-Child Policy have left a deep social imprint, including unaddressed trauma for those who underwent forced abortion or sterilization,6 children who were never registered, and families ruined by hefty non-compliance fees. All this has fostered generations of young adults accustomed to small families and intensified their reluctance to have more children. The institutional legacy of quotas and coercion also continues to constrain comprehensive sexual-health education, particularly around topics deemed “non-procreative.”7

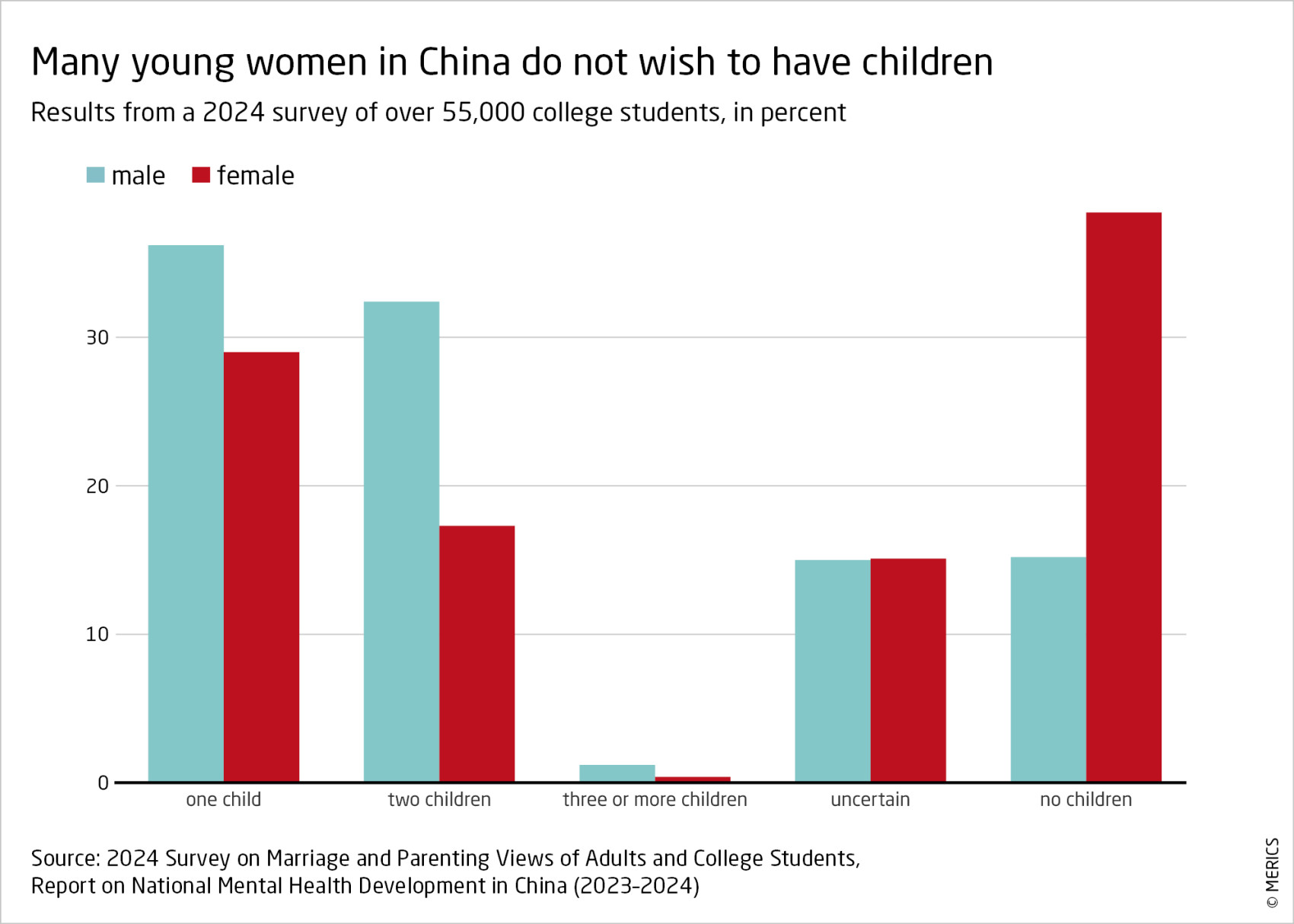

China’s family‐planning governance has long operated through a dense hierarchy of surveillance, mandatory procedures, and performance‐based incentives - which have profoundly shaped women’s bodily autonomy. Highly coercive practices led to discontent, including violent incidents, and were heavily criticized both inside and outside China.8 The widespread cultural preference for boys meant these policies also resulted in mass abortions, and infanticide or abandonment of girls. They have caused an unintended gender gap that complicates recent pro-marriage and birth policies.9 As a result, many younger women now repudiate motherhood (see exhibit 2).10

Ironically, the government is now subsidizing research and population surveys11 to better understand the compounding effects caused largely by their own coercive measures12 – and how to address the current problem.

China reversed its family planning policies, with control

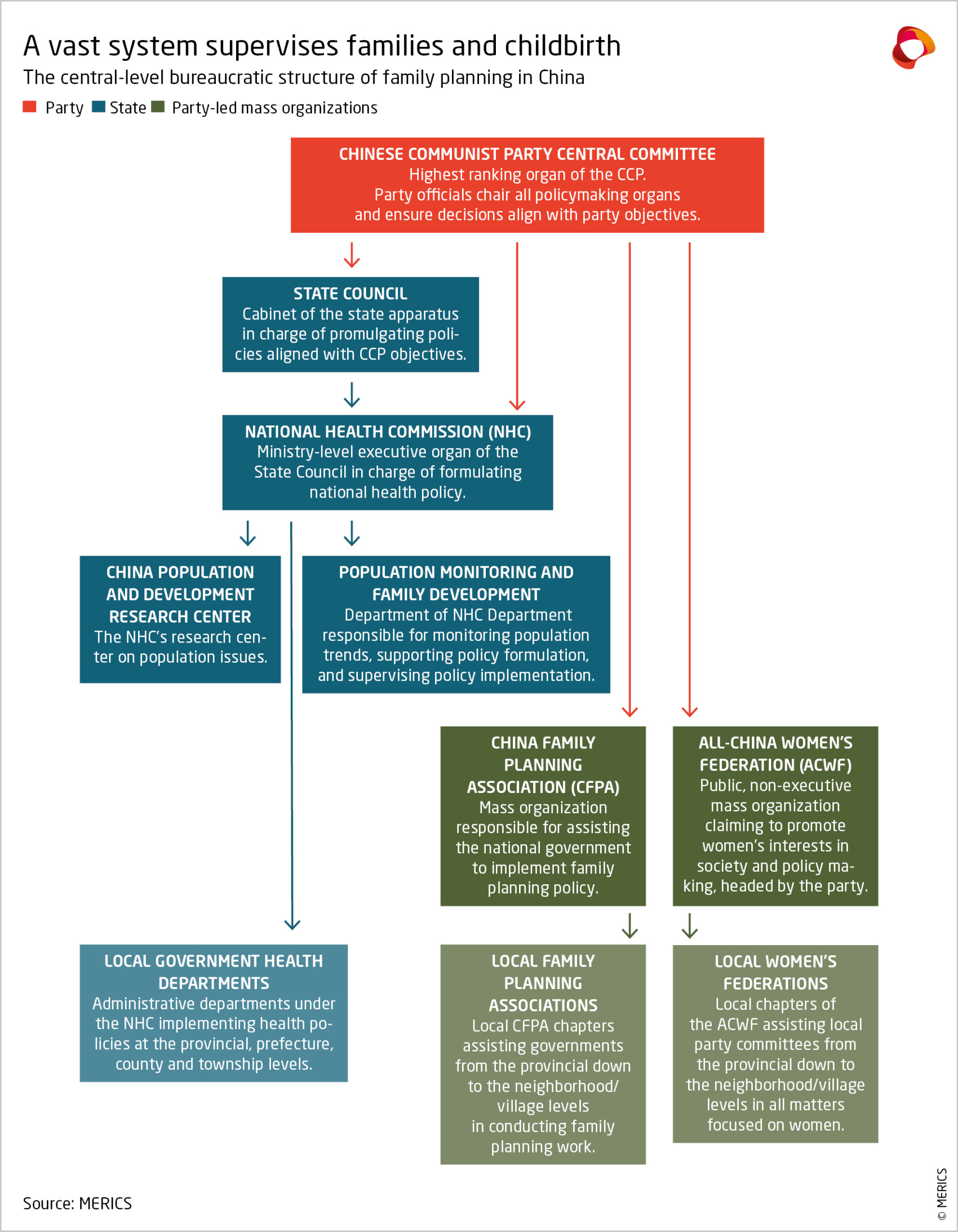

One of China’s unique features is the sprawling bureaucratic network it has built to deal with family planning, policymaking and implementation. The system intersects across several party organs, ministries and mass organizations, and reaches from the top political echelons down to neighborhood and village committees (see exhibit 3).

China’s family‐planning system has gone through three main stages in the 21st century:

- In the early 2000s, a dedicated, ministry‐level body – the National Population and Family Planning Commission, was created;

- In 2013, that was merged with the Ministry of Health, forming the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China;

- In 2018, the commission was restructured again and took its current name of National Health Commission. While no longer in the name, family planning remains a core part of the commission with a dedicated department.

The system has transitioned from a stand-alone, quota-driven commission to a branch of the broader healthcare system. The existence of a central bureaucracy for family planning highlights how deeply rooted social engineering is in the party state’s political DNA. The changes reflect the ongoing shift from strict birth-control towards encouraging higher birthrates and supporting reproductive health.

Shifts are also occurring within broader national strategic frameworks. According to China’s party state news agency Xinhua, the annual government work report delivered at the People’s Congress in March 2025 included, for the first time, a commitment to provide childcare subsidies. It cited this step and other national plans as signals that birth promotion has achieved “national strategic priority” status.13

Even the National Security White Paper published in May 2025 included the phrase “Enhance the policy framework and incentives that support childbirth”.14 Featuring reproduction-friendly policies and systems in the national security discourse effectively securitizes the issue, making clear that Beijing regards birthrates as politically sensitive.

Restrictions on births have been loosened, and fiscal penalties are being phased out, but the party state’s interventionist approach to family planning is largely unchanged. It continues to rely on administrative planning and a legal discourse marked by notions of social engineering. Instead of leaving childbirth entirely to its citizens, it insists on updating legal text on the matter, writing in a new legal limit of three children and normative statements on marriage and family.

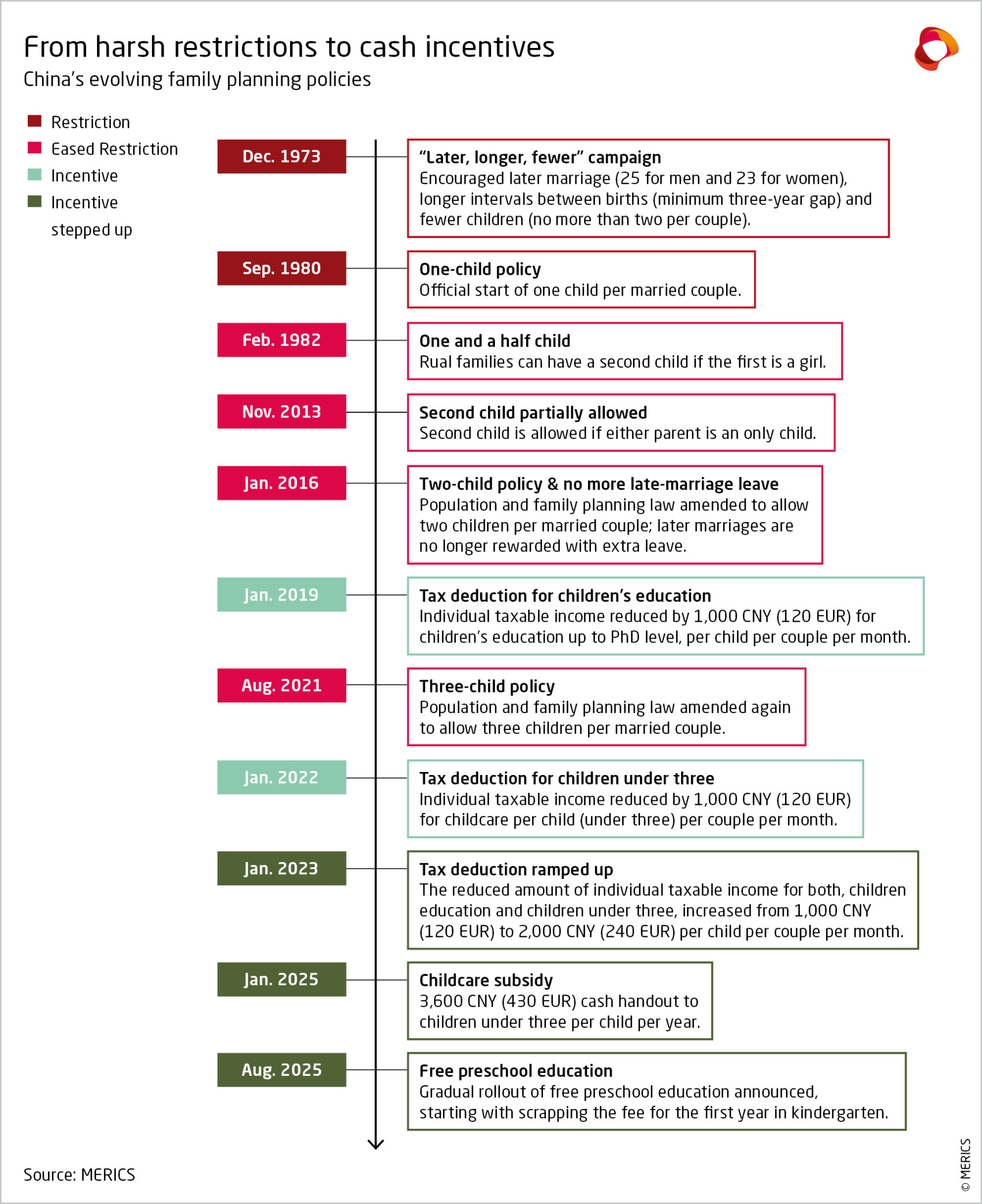

The core statutory framework, built on the 2001 Population and Family Planning Law, has been amended three times to shift away from restrictive birth quotas towards supportive measures (see exhibit 4).

For instance, the amended 2021 Population and Family Planning Law15 emphasizes that “family is the cell of society” and that women have a “natural role in childbearing and childrearing”. The law stipulates that “the state supports marriage and childbearing at the appropriate age”.16 That age is 23 – 28 years for women, while for men it can be later, according to commentary published by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).17

The biological reasons given, such as “high-quality eggs”,18 have stirred up debates on permitting egg-freezing for single women, which is currently illegal. Nor are same-sex couples allowed access to fertility support services. While repeated proposals to allow egg-freezing for single women have not yet led to legislative changes, authorities including the National Health Commission have floated a possible change of regulations in response to demographic challenges.19

In 2022, the State Council’s Development Research Centre explained this logic, saying the three-child limit was necessary to avoid “repeating the mistake of excessive population growth in the early days of the founding of New China.”20 This approach further exacerbates the gap between policymaking and the general public mood, wishes and stances on childbirth.

The party’s efforts to boost births begin at the grassroots

Despite the focus on centralized planning in reproductive policy, local implementation is what impacts citizens’ lives and women’s bodies the most.

In June, the government announced all hospitals with more than 500 beds would be required to offer epidural anesthesia by the end of 2025, while those with more than 100 must do so by 2027. Currently, only 30 percent of pregnant women can get anesthesia during childbirth in China.21 The percentage doesn’t convey discrepancies between urban and rural hospitals. It also doesn’t account for the number of C-sections, which has historically been high compared to other countries,22 although the trend is now reversing.23

While worries about birth pain are a big contributor to women’s hesitancy to have children,24 making wider access to epidural anesthesia a welcome move, the resource constraints across the sector remain. The policy’s long-term success will largely depend on how local resources are allocated. Its impact on changing women’s attitudes towards childbirth will certainly take much longer to manifest.

On 28 July, the CCP’s Central Committee and the State Council released the "Implementation Plan for the Childcare Subsidy System", which stipulates that, from 1 January 2025, all provinces need to issue subsidies of CNY 3,600 (EUR 430) per child per year, until they are aged three.

This is a small amount given the average yearly cost of raising a child is CNY 26,944 (EUR 3,214).25 It is not yet clear how this payment will intersect with subsidies already being provided at lower administrative levels.26

Plans to provide universal free pre-school had been in the works for a long time,27 and finally on 5 August the State Council announced that from September 2025, there would be a gradual rollout of free preschool education. It stipulated that public kindergartens would be exempted from childcare education fees for the first year of preschool, while the fees for private ones will be reduced.28

Local initiatives predate national incentives

So far, the majority of parent-supportive initiatives have come from local governments, with new measures announced almost daily. Local cash subsidies and maternity leave extensions, for instance, predate national schemes and are often more generous (see Exhibit 5).

A few local governments have scored some short-term successes, for instance in the prefecture-level city of Panzhihua, in Sichuan province, and the county-level city of Tianmen, in Hubei. Reportedly, Panzhihua recorded positive population growth for four consecutive years as it was the first city to offer childcare subsidies. Recently, Tianmen was praised for its “tangible and holistic pro-birth policies”, including baby bonuses, childcare subsidies, maternity leave allowances and housing incentives.29 Since 2023, the Tianmen municipal government has informed its birth support polices with questionnaire surveys of mothers, household visits and more than 800 symposiums, bringing results that are now the subject of study inspections from all over China.30

But the map below shows that, while the incentives have become relatively widespread, they remain uneven and, at times, too generic. They often fail to target particularly vulnerable populations, or address people’s deeper needs besides economic worries – for instance, people’s reluctance to get married.

A big issue contributing to China’s population decline is the growing unwillingness to get married. According to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs, 2024 had the lowest number of marriages ever recorded (6.1 million – a fall of 20.5 percent from 2023), after an entire decade of steep decline.31

The China Family Planning Association (CFPA) and All-China Women’s Federation, both mass organizations under the leadership of the CCP’s Central Committee, have been in charge of delivering party messaging to the masses and ensuring central directives are implemented at the local level.

In 2023, President Xi Jinping proclaimed that the country and its women need to “actively cultivate a new culture of marriage and childbearing”. A stream of initiatives is aimed at achieving this goal:

- Marriage benefits. Extended marriage leave was rolled out in most provinces and cash handouts to young newlyweds are regularly announced at local levels.32 The legal age for marriage is 20 for women and 22 for men, though Chinese experts have been pushing the government to lower it because of demographic challenges.33 A reduction is likely soon.34

- Controversial propaganda campaigns. Large and persistent propaganda campaigns have been aimed at the public, both online and offline. To get free promotional content, for instance, the CFPA launched a competition for slogans praising the three-child policy. This quickly backfired, as people mostly criticized the initiative and highlighted the CFPA’s role in previous coercive campaigns under the One-Child Policy.35 Other much criticized initiatives included local authorities cold-calling married women to ask about their plans for children.36

- Crackdowns on rural customs. New laws and regulations tackle what are perceived as outdated rural customs thought to create higher barriers for young people, such as expensive weddings and high bride prices. The party committee of the National Health Commission has spoken about the need to “promote the reform of marriage customs.”37

- Mass weddings. Local Women’s Federations have organized mass weddings to give young people an affordable wedding, complete with a certificate praising their patriotic gesture.38

- Educational courses on ”healthy families” and ”marriage and love.” For example, in December 2024, a state-run publication from the National Health Commission called on universities to set up “marriage and love education courses” to encourage students to think positively about marriage.39

All these initiatives add fuel to pre-existing family pressures to get married. Economic drivers have emerged around them, like new dating apps for parents hunting suitors to wed their children.40 Rather than increasing the number of weddings, which continue to decline, many of these initiatives have spurred criticism and backlash.

For the CCP, demographic security trumps women’s rights

Official narratives

“Marriage and childbirth are not only a family affair related to personal happiness, but also a major event for the survival and development of the country and the nation.” (China Family Planning Association)41

The party-state's shift towards encouraging childbirth is shaping official discourse around women's rights and gender equality, topics that have been supplanted by population concerns.

Xi Jinping has framed “population security” as a national concern and people as a strategic asset that needs meticulous management to prevent a demographic crisis from a fast-aging population and shrinking work force.42 “Population security” appears in the party-state's development strategies, with leaders calling for “supportive reproductive measures” to assist the ”development of a high-quality population.”43

For now, Beijing is walking a tightrope between loosening restrictions, focusing on incentives, and promoting women’s personal health. However, carrots could soon turn into sticks if birthrates do not increase.

This balancing act is evident in the National Population Development Plan (2016-2030). Issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), an organ of the State Council in charge of policy coordination, the plan promotes a “birth-supporting system.” While the plan, as well as the recently revised Population and Family Planning Law and local regulation, speaks of better rights and benefits for women, its focus on population growth as a strategic concern leans towards viewing women as resources.44

Despite mentions of preserving women’s interests, many policy initiatives are still problematic. Parental leave, for example, remains gendered. Although the 2022 law on the protection of Women’s Rights and Interests “supports the establishment of parental leave,” provinces often retain the right to grant paternity leave at their discretion, not uniformly, reinforcing expectations that women alone should shoulder child‐rearing burdens, and disadvantaging them further in the workplace, where women have historically faced great discrimination.45

Some propaganda initiatives have prompted women to have children while studying.46 This raises questions about how marriage and parenting pressure at younger ages might impact women’s educational outcomes in the future. It remains to be seen whether the government plans to promote such a trend, or if it was a sporadic case, and it deserves further monitoring.

There is a movement towards restricting abortions for ”non-medical reasons,” which limits women’s reproductive rights and supports a pro-natalist agenda,47 together with limits on vasectomies.48 In 2023, a Chengdu court ruled that abortion without the husband’s consent is a ”violation of men’s right to reproduction,”49 setting a troubling precedent.

Non-medical abortions were previously banned to prevent sex-selective abortions that favored boys, and sex-selection is illegal at any stage. A 2016 regulation by the National Health Commission explicitly outlawed the practice. However, the China Women’s Development Guide50 restrictions on non-medical abortion as a matter of the population’s reproductive health, a shift that has sparked concerns that barring access to abortions could be used to boost birth rates.51

Official rhetoric and media coverage frequently emphasize the importance of women’s roles in “family harmony,” “social stability,” and “national rejuvenation,” linking individual reproductive choices with the collective national interest.52 This instrumentalization is evident in campaigns urging a “new marriage and childbearing culture” that promotes earlier marriage and childbearing, and in policy proposals like the controversial “No Child Tax,” which would penalize childless adults.53

Pro-birth policies are often met with criticism

“First forced abortions, now pressured into pregnancy.” (Chinese netizen online, What’s On Weibo)

The intensification of party-state efforts to shape public attitudes toward marriage and childbearing through campaigns and the new family planning networks has generated widespread resistance. Women’s voices are increasingly asserting themselves in the face of policy shifts and societal expectations.

In an insulated information environment such as China’s, it remains difficult to classify discontent at a large scale. However, topics related to population and childbirth are highly debated on social media and, almost without fail, complaints arise after every new policy announcement, providing insightful snippets into public sentiment.

The “No Child Tax” proposal, for example, was met with outrage online. Many commentators drew parallels with the coercive One-Child Policy era and expressed fears of renewed state control over women’s bodies. Comments such as “First forced abortions, now pressured into pregnancy” encapsulated the sense of frustration and distrust.54

Women have also used online platforms to highlight the economic, social, and personal barriers to childbearing, such as the high cost of raising children (which a new study said was now higher in China than in the United States and Japan),55 career penalties for mothers, and the lack of affordable childcare.

The unaffordability of childcare is particularly difficult for rural young people who have moved to the city for work, often still in precarious financial conditions, and who lack family support. Sanlian Lifeweek magazine reported that “having live-in nannies, bringing the elderly to the city to help, or sending children back to their hometowns all involve various obstacles for highly educated and career-oriented dual-income families.”56 This is creating a phenomenon known as “new left-behind children” – where young professional couples are sending their city-born children back to their hometowns.

These discussions often challenge the state’s narrative that declining birth rates are primarily a matter of individual or moral failings.57 They highlight the paradox facing the government: authorities keep promising more and better services, yet existing ones are struggling to stay operational due to the lack of children. Maternity wards and early childhood centers have shut down across the country.58

Official discourse increasingly calls for “shared parenting responsibilities” and gender equality, especially in more economically advanced provinces, yet most women continue to bear the brunt of reproductive and caregiving labor. Policies such as extended maternity leave, or flexi-working “mother gigs” (妈妈岗) fail to give protection against workplace discrimination, reinforce low wages and impediments to career progression.59 They are often criticized for reinforcing the notion that childrearing is primarily a woman’s duty, rather than promoting genuine equality.60

Moreover, the state’s efforts to promote marriage and childbearing exacerbate the discrimination and social stigma experienced by women who choose to remain single and/or childless. Online discussions frequently highlight these contradictions, as women articulate their desire for greater autonomy, respect and support.61

And it’s not just women being critical. When some city governments began offering cash handouts to women who got married before age 35, they were met with ironic dismissals online, as people doubted CNY 1,500 (EUR 179) would persuade anyone to get married62 – especially considering the price of weddings, high divorce rates and lingering traditions around bride prices.

Some criticism flowed from inside the party itself. Discussions about pro-birth policies have centered on the pressure on businesses to bear the brunt of supporting mothers, thereby worsening gender discrimination. Caixin reported estimates that maternity leave costs companies between CNY 32,000 (EUR 3,840) and CNY 95,900 (EUR 11,500) for a female employee having one to three children.63 Government subsidies remain meager in comparison.

People like Li Chengxia (李承霞), deputy to the 14th National People's Congress and chairman of the Women's Federation at a Jiangsu company, have been outspoken in criticizing the latest policies. "This cost-pressure directly leads to discrimination against women of childbearing age when recruiting, forming an unspoken rule of not recruiting women aged 25-35, not hiring married people without children, and not accepting mothers with second children," she said.64

Such widespread discontent, and the limited results achieved so far in raising the birth-rate, suggest a bleak picture for China’s population goals.

The pro-natalist approach will not solve demographic woes

The CCP appears ill-positioned to solve the looming population crisis, and the risk for China to get old before it gets rich is imminent. Action has begun late, and authorities can now only attempt to soften the blow of the country’s demographic decline. Still, reasonably successful pro-natalist policies will be consequential for China’s economic development, and hence for everything connected to it – China’s military prowess, its technological advancement, and the prosperity of the many countries that depend on China’s economic growth.

Against this backdrop, Beijing’s securitization of population growth, with its direct impact on citizens’ livelihoods and freedom of choice, was a predictable reflex. But compliance is far from assured and, in this instance, enforcement is much harder. It cannot be excluded that the party state will further increase pressure. Should fast population growth become a hard security issue, more authoritarian approaches to increase birth rates, and thus to individual rights and gender equality, are likely.

Central to the issue is also the cost of social services, especially the growing cost of elderly care and healthcare in a society that has a predominantly elderly population. Even with a fast uptick in births in the coming years, it will take two decades until effects in public coffers materialize. It is thus uncertain that long-term financial effects of demographic policy will come to fruition, whereas labor market developments such as automation and informatization are likely to have a much more immediate effect on economic growth and public tax revenue.

Also at stake is the legitimacy of a party whose every move is being watched and scrutinized. The leadership faces a dilemma: reverting to social engineering that renders childbirth a patriotic duty and creates systems that guide age- and gender-specific behavior (i.e., women have children early and stay at home), or continue a more rights-based approach that favors socio-economically supportive policy, making childbirth more affordable, and leaves specifics of when and how up to individual choice. Given the grim history of family planning policy, the party risks backlash if it acts too intrusively. Recent initiatives point to a somewhat mixed approach: cash subsidy schemes and eased access to education aims at lessening the relatively high economic burden of having children. On the other hand, Beijing increases the discourse of patriotic duties and strengthens efforts to nudge young women into traditional gender and childbearing roles.

Of the many concerned groups, women of childbearing age are central to the project’s success. As the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on gender equality and women’s empowerment turns 30 in October 2025, and Beijing prepares to host global summit on this occasion, there will be a swathe of big and bold statements on China’s progress in this domain, which are unlikely to represent the lived reality of most women across the country. Beijing likes to stress China‘s progress in the domain of gender equality and women‘s rights, and delegations should be prepared to raise these issues, especially around women’s reproductive and labor rights.

At a time of global regression on women’s rights, developments in a country as influential as China are crucial to monitor global development goals. Beijing’s drive for increasing births threatens to reverse much of the slow progress achieved over decades. Additionally, excessively coercive measures may cause domestic turmoil that, in extreme cases, could threaten the regime’s stability. Movements such as lying flat, and not least the reluctancy of young Chinese to have children in the current economic environment, show that pushing alone is unlikely to work even in better situated parts of the population.

Our findings show that the party state remains in a technocrat mindset when it comes to demographic planning. Beijing is still reluctant to go beyond economic incentives and ideology to tackle the real issues faced by women and families, such as systemic discrimination and societal obstacles, as well as the enormous socio-economic burden of having children in China, which remain the main causes of people’s unwillingness to marry and procreate. The current efforts are likely to be too little too late, and therefore, China’s looming demographic decline will continue to be a serious challenge in the coming decades. It also highlights a clash in Beijing’s evolving playbook, where dated and more authoritarian policy making collides with more supportive and enabling approaches to modern socio-economic issues.

- Endnotes

1 | de Guzman, Chad (2023). “China Is Desperate to Boost Its Low Birth Rates. It May Have to Accept the New Normal.” Time. August 18. https://time.com/6306151/china-low-fertility-trap-birth-rate-policies/. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

2 | CGTN (2024). “Graphics: A glance at China’s age distribution and labor force.” September 11. archive.is/m6Jb2. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

3 | National Bureau of Statistics of China 国家统计局 (2013). “2012年国民经济和社会发展统计公报” (Statistical Communiqué on the 2012 National Economic and Social Development). February 22. 2012年 - 国家统计局. Accessed: 12.09.2025. National Bureau of Statistics of China 国家统计局 (2024). “2024年全国居民收入和消费支出情况” (2024 Situation of National Residents’ Income and Consumption Expenditure). January 17. https://archive.is/BthZW. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

4 | China Digital Times (2021). “兽楼处|反对者的四十年” (Shòu Lóu Chù | Forty Years of Opponents). May 18. https://chinadigitaltimes.net/chinese/666157.html. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

5 | National Health Commission Party Leadership Group 中共国家卫生健康委党组 (2022). “谱写新时代人口工作新篇章” (Composing a New Chapter in Population Work in the New Era). Qiushi. August 1. archive.is/wip/ZZVF3. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

6 | From the 1980s through the early 2000s, local cadres were evaluated in part on “sterilization quotas”, which generated incentives to pressure people to undergo sterilization or to be fitted with an intrauterine device soon after they’d had their permitted child(ren). Refugee Review Tribunal, Research & Information Services Section (2007). “China – Guangdong – Family planning – One-child policy – Forced abortions – Fines – Penalties – Water stream test.” Research Response Number: CHN32063, Australia, 17 August 2007. https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1157350/2107_1310383245_chn32063.pdf. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

7 | Wee, Sui-Lee (2017). “After One-Child Policy, Outrage at China’s Offer to Remove IUDs.” The New York Times. January 7. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/07/world/asia/after-one-child-policy-outrage-at-chinas-offer-to-remove-iuds.html. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

8 | Cheng, Rita (2022). “Women harmed by China’s draconian family planning policies still seek redress.” Radio Free Asia. April 8. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/redress-04082022084633.html. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

9 | The Economist (2025). “China’s alarming sex imbalance.” February 20. https://www.economist.com/china/2025/02/20/chinas-alarming-sex-imbalance. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

10 | Lu, Shen (2018). “China’s once-unwanted daughters have grown up — and now they shun motherhood.” The Wall Street Journal. April 21. https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-once-unwanted-daughters-have-grown-up-and-now-they-shun-motherhood-11510572. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

11 | National Health Commission of the PRC 国家卫生健康委员会 (2025). “国家卫生健康委办公厅关于组织开展2025年人口高质量发展研究揭榜攻关活动的通知” (Notice of the General Office of the National Health Commission on Launching the 2025 Population High-Quality Development Research Project). March 25. https://archive.is/SQysJ. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

12 | Li, Hongbin; Meng, Lingsheng; Miller, Grant; Yang, Hanmo (2025). “Bureaucratic Incentives and Effectiveness of the One Child Policy in China.” Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions/FSI Working Paper (NBER Working Paper No. 33741). May 5. https://sccei.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/bureaucratic-incentives-and-effectiveness-one-child-policy-china. Accessed: 11.09.2025.

13 | Xinhua 新华社 (2025). “Subsidies, services, social shifts: China’s strategic push for a birth-friendly future.” March 21. English.news.cn. https://archive.is/VljS0. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

14 | State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 (2025). “新时代的中国国家安全” (China’s National Security in the New Era). Xinhua. May 12. https://archive.is/dW2J4. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

15 | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress 全国人民代表大会常务委员会 (2021). “中华人民共和国人口与计划生育法” (Population and Family Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China). National People’s Congress of the PRC. September 3. https://archive.is/iVJBp. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

16 | Peking University Law Press 北京大学法宝. “中华人民共和国人口与计划生育法” (Population and Family Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China). https://archive.is/BgiCD. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

17 | Chinese Academy of Sciences 中国科学院 (2009). “探索可持续发展战略纲要启动会举行” (The Launching Conference for the Outline of the Sustainable Development Strategy Was Held). June 8. https://archive.is/0y1XY. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

18 | Gulou District Health Bureau 鼓楼区卫健局 (2024). “最佳生育年龄你知道吗?” (Do You Know the Best Age for Childbearing?). Fuzhou Municipal People’s Government, Gulou District 福州市鼓楼区人民政府. April 7. https://archive.is/8vx0w. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

19 | National Health Commission of the PRC 国家卫生健康委员会 (2021). “关于政协十三届全国委员会第三次会议第2049号(社会管理类144号)提案答复的函” (Reply to Proposal No. 2049 (Social Management No. 144) of the Third Session of the 13th CPPCC National Committee). January 19. https://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/tia/202101/4e315cef9da840048ffb377c56c8c64d.shtml. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

The Paper 澎湃新闻. “国内首例单身女性冻卵案” (China’s First Case of Egg-Freezing by a Single Woman). thepaper.cn. https://archive.is/G1B63. Accessed: 12.09.2025. CCTV (2019). “全国首例‘冻卵’案背后:政策法规滞后,不开口子特别审慎” (Behind China’s First Frozen-Egg Case: Lagging Policies and Regulations, Not Opening the Door, Special Prudence). December 26. https://archive.is/vDhQR. Accessed: 12.09.2025.20 | Development Research Center of the State Council 国务院发展研究中心课题组 (2022). “促进我国人口长期均衡发展” (Promoting the Long-Term Balanced Development of China’s Population). January 19. https://archive.is/pDk3B. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

21 | Reuters (2025). “China to make all hospitals offer epidurals to incentivize childbirth.” CNN. June 9. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/06/09/china/china-child-birth-epidural-intl-hnk. Accessed: 12.09.2025.

22 | Huang, Yanzhong (2014). “China Should Be Concerned by Overuse of Cesarean Sections.” Council on Foreign Relations. June 25. https://www.cfr.org/blog/china-should-be-concerned-overuse-cesarean-sections. Accessed: 13.09.2025. Owen, Lara and Razak, Aidila (2019). “China putting women’s salaries at risk over pregnancy, study says.” BBC News. March 3. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-46265808. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

23 | Tang, Di; Laporte, Audrey; Gao, Xiangdong; Coyte, Peter C. (2022). “The effect of the two-child policy on cesarean section in China: Identification using difference-in-differences techniques.” Midwifery, Vol. 107, April 2022, 103260. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0266613822000122?via%3Dihub. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

24 | Kitty & Acher (2022). “你生吗?《35岁以下生育意愿调查报告》” (Will You Have Children? “Fertility Intention Survey Report for Women Under 35”). 我要WhatYouNeed (Weixin). May 18. Guangdong. https://archive.is/AM47C. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

25 | Qi, Liyan (2025). “China’s new plan to encourage more births is underwhelming.” The Wall Street Journal. July 17. https://www.wsj.com/world/china/chinas-new-plan-to-encourage-more-births-is-underwhelming-c8d23df4. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

26 | General Office of the CPC Central Committee and General Office of the State Council (2025). “受权发布丨中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《育儿补贴制度实施方案》” (Authorized Release: The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council Issued the “Childcare Subsidy Implementation Plan”). Xinhua. July 28. https://archive.is/m26Lc. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

27 | Xinhua 新华社 (2025). “李强主持召开国务院常务会议 听取当前防汛抗旱情况和下一步工作安排汇报 审议通过《自然灾害调查评估暂行办法》 部署逐步推行免费学前教育有关举措” (Li Qiang Presides Over State Council Executive Meeting: Heard Reports on Current Flood Control and Drought Relief and Next Steps, Approved the “Interim Measures for Natural Disaster Investigation and Assessment,” and Deployed Measures to Gradually Implement Free Preschool Education). July 25. https://archive.is/mz8p7. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

28 | General Office of the State Council 国务院办公厅 (2025). “国务院办公厅关于逐步推行免费学前教育的意见” (Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Gradually Implementing Free Preschool Education). August 5. https://archive.is/7zVHH. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

29 | Xinhua (2025). “Policy briefing on improving TCM quality and promoting high-quality development of TCM industry.” The State Council Information Office of the PRC. March 21. https://archive.is/jUaAc. Accessed: 13.09.2025.

30 | Zhong, Yuhao 钟煜豪 (2025). “天门市委书记算账:3年投入3亿多鼓励生育,全市有望多出生3000多个孩子” (Tianmen Party Secretary Does the Math: Over 300 Million Yuan Invested in 3 Years to Encourage Births, City May See Over 3,000 More Children Born). The Paper 澎湃新闻. July 27. https://web.archive.org/web/20250828131025/https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_31249052. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

31 | Gan, Nectar (2025). “New marriages in China crash to record low, while divorces on the rise.” CNN. February 10. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/02/10/china/china-marriage-registrations-record-low-2024-intl-hnk/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

32 | Xinhua (2025). “More Chinese provinces extend marriage leave in family support push.” State Council Information Office of the PRC. June 11. https://archive.is/WkszF. Accessed: 14.09.2025. Reuters (2023). “Chinese county offers 'cash reward' for couples if bride is aged 25 or younger.” August 29. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinese-county-offers-cash-reward-couples-if-bride-is-aged-25-or-younger-2023-08-29/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

33 | Du, Qiongfang (2025). “CPPCC member advocates lowering legal marriage age to enlarge fertility population base.” Global Times. February 24. https://archive.is/NOSBa. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

34 | Observer 观察者网 (2025). “全国政协委员:建议降低法定结婚年龄至18岁,以释放生育潜能” (CPPCC Member: Proposal to Lower the Legal Marriage Age to 18 to Unlock Fertility Potential). Sina Finance 新浪财经. February 24. https://archive.is/WQBGV. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

35 | Yang, Samuel (2021). “China holds competition for public to come up with three-child policy slogans but many are unimpressed.” ABC. August 13. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-14/china-three-child-policy-competition-for-slogans/100372766. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

36 | Zheng, William (2024). “Chinese government workers call up women to urge them to have babies.” South China Morning Post. October 28. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3284192/chinese-government-workers-call-women-urge-pregnancy-latest-birth-rate-push. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

37 | Party Leadership Group of the National Health Commission 中共国家卫生健康委党组 (2022). “谱写新时代人口工作新篇章” (Composing a New Chapter in Population Work in the New Era). Qiushi Theory 求是. August 1. https://archive.is/FUzJg. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

38 | Xinhua 新华社 (2024). “全国万人集体婚礼 ‘家国同庆 见证幸福’” (Nationwide Mass Wedding: “Celebrating the Nation Together, Witnessing Happiness”). Xinhua Net 新华网. September 23. https://archive.ph/chrSF. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

39 | Olcott, Eleanor; Liu, Nian; and Wang, Xueqiao (2023). “China steps up campaign for single people to date, marry and give birth.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5fdf42e1-2975-4c99-9031-a9f73c2251be. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

40 | Fan, Yiying and Chen, Zhenyang (2025). “We Do: On China’s New Dating Apps, Parents Make the Match.” Sixth Tone. July 16. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1017358. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

41 | China Family Planning Association 中国计划生育协会 (2023). “《新时代婚育文化建设倡议书》来啦!” (Here Comes the “Proposal on Building a New Era Marriage and Childbearing Culture”!). Qingyuan Municipal Health Department 清远市卫生健康局. May 17. https://archive.is/rwKeC. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

42 | Xi Jinping 习近平 (2024). “以人口高质量发展支撑中国式现代化” (Supporting Chinese-Style Modernization through High-Quality Population Development). Qiushi Journal 求是杂志. November 15. archive.is/hPUWc. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

43 | CCP Central Committee and State Council 中共中央 国务院 (2021). “关于优化生育政策 促进人口长期均衡发展的决定” (Decision on Optimizing the Birth Policy to Promote the Long-Term Balanced Development of the Population). Xinhua. June 26. https://archive.is/cr986. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

44 | State Council of the PRC 中华人民共和国国务院 (2016). “国务院关于印发国家人口发展规划(2016—2030年)的通知” (Notice of the State Council on Issuing the National Population Development Plan (2016–2030)). State Council Document No. 87. https://archive.is/rUg2A. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

45 | Human Rights Watch (2021). “Take Maternity Leave and You’ll Be Replaced: China’s Two-Child Policy and Workplace Gender Discrimination.” June 1. https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/06/01/take-maternity-leave-and-youll-be-replaced/chinas-two-child-policy-and-workplace. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

46 | Li, Siwen 李思文 (2016). “大学生讲述在校生子:有大三生已是二孩妈,大多女生称不后悔” (College Students Talk About Giving Birth While Still in School: Some Juniors Already Have Two Children, Most Female Students Say They Do Not Regret It). The Paper 澎湃新闻. May 21. https://archive.is/TzNjm. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

47 | Mu, Feng 木风 (2022). “中国要求各地减少堕胎 17个政府部门联名发文件极其罕见” (China Requires Localities to Reduce Abortions: 17 Government Departments Jointly Issue an Extremely Rare Document). VOA Chinese 美国之音中文网. August 17. https://www.voachinese.com/a/china-to-discourage-abortions-to-boost-low-birth-rate-20220816/6703759.html. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

48 | https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-birth-control-vasectomy/2021/12/09/c89cc902-50b8-11ec-83d2-d9dab0e23b7e_story.html

49 | Population Matters (2025). “China’s Reproductive Rights: Calls for a Childbirth Culture.” February 6. https://populationmatters.org/news/2025/02/chinas-reproductive-rights-calls-for-a-childbirth-culture/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

50 | National Health Commission of the PRC 国家卫生健康委员会 (2016). “禁止非医学需要的胎儿性别鉴定和选择性别人工终止妊娠的规定” (Provisions on Prohibiting Fetal Sex Identification and Sex-Selective Abortion for Non-Medical Needs). April 20. https://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/c100048/201604/e23c291bb0c8468c87a8f514a7bf08dd.shtml. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

51 | Zhen Ni Te 珍妮特 (2022). “中国为遏止人口下降 打算限制‘非医疗理由’的堕胎” (China Plans to Restrict Abortions for “Non-Medical Reasons” to Curb Population Decline). Radio France Internationale (RFI) 法国国际广播电台. February 19. https://www.rfi.fr/cn/中国/20220218-中国为遏止人口下降-打算限制-非医疗理由-的堕胎?. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

52 | Xinhua 新华社 (2023). “Xi stresses organizing, motivating women to contribute to Chinese modernization.” State Council of the PRC 中华人民共和国国务院. October 31. https://archive.is/pnNnA. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

53 | What’s on Weibo Team (2018). “China’s Proposed ‘No Child Tax’ Stirs Controversy: ‘First Forced Abortions, Now Pressured Into Pregnancy’ Whose Right Is It to Decide Whether or Not to Have a Second Child – and Who Pays the Price?” What’s on Weibo. August 18. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinas-proposed-no-child-tax-stirs-controversy-first-forced-abortions-now-pressured-into-pregnancy/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

54 | What’s on Weibo Team (2018). “China’s Proposed ‘No Child Tax’ Stirs Controversy: ‘First Forced Abortions, Now Pressured Into Pregnancy’ Whose Right Is It to Decide Whether or Not to Have a Second Child – and Who Pays the Price?” What’s on Weibo. August 18. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinas-proposed-no-child-tax-stirs-controversy-first-forced-abortions-now-pressured-into-pregnancy/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

55 | Stanway, David (2022). “Bringing up a child costlier in China than in U.S., Japan - research.” Reuters. February 23. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-child-rearing-costs-far-outstrip-us-japan-research-2022-02-23/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

56 | Jiang, Yuqi 江郁琦 (2025). “小镇出身,名校毕业,我却把孩子送回老家当‘留守儿童’” (From a Small Town to a Prestigious University, Yet I Sent My Child Back Home as a “Left-Behind Child”). Sanlian Life Weekly 三联生活周刊. July 15. https://archive.is/F36Qr. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

57 | Koetse, Manya (2023). “From Baby Benefits to Bonus Points: Chinese Measures to Boost Birthrates.” What’s on Weibo. April 2. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/from-baby-benefits-to-bonus-points-chinese-measures-to-boost-birthrates/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

58 | Zhao, Jinzhao; Pan, Rui; and Wang, Xintong (2024). “In Depth: Maternity Wards Are Latest Victim of China’s Falling Birthrate.” Caixin Global. June 19. https://www.caixinglobal.com/2024-06-19/in-depth-maternity-wards-are-latest-victim-of-chinas-falling-birthrate-102207848.html. Accessed: 14.09.2025. Stevenson, Alexandra; Wang, Zixu (2025). “China’s Population Declines for 3rd Straight Year.” The New York Times. January 16. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/16/business/china-population-births-deaths.html. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

59 | The Economist (2025). “China claims to want women to have children and a career.” August 14. https://www.economist.com/china/2025/08/14/china-claims-to-want-women-to-have-children-and-a-career. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

60 | Workers’ Daily 工人日报 (2025). ““妈妈岗”,实现灵活就业之后……” (“Mom Jobs”: After Achieving Flexible Employment…). Xinhua. February 25. https://archive.is/5T4Yy. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

61 | Koetse, Manya (2023). “From Baby Benefits to Bonus Points: Chinese Measures to Boost Birthrates.” What’s on Weibo. April 2. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/from-baby-benefits-to-bonus-points-chinese-measures-to-boost-birthrates/. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

62 | Sanxia Business Daily 三峡商报 (2024). “女性35岁前结婚,奖励1500元!一地最新发文” (Marry Before 35, Get 1,500 Yuan! Latest Local Directive). Sina Finance 新浪财经. November 2. https://archive.is/cqiPq. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

63 | Yang, Hui 杨慧 (2022). “三孩政策下企业生育成本负担及对策研究———基于延长产假的分析” (Research on the Burden of Enterprise Childbearing Costs and Countermeasures Under the Three-Child Policy — Based on the Extension of Maternity Leave). Population and Economy 《人口与经济》. No. 6, pp. 17–31. https://archive.is/wbzE4#selection-151.0-233.26. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

64 | Liao, Baoping 廖保平 (2025). “鼓励生育不能是‘政策请客,企业埋单’” (Encouraging Childbirth Cannot Be “Policy Treats, Enterprises Pay the Bill”). 163.com. March 12. https://archive.is/kLAUY. Accessed: 14.09.2025.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank MERICS intern Hailey Law for her research support, insights and keen eye for detail; former MERICS intern Ariane Kolden for her research support; and Dalia Parete, researcher at the Taiwan-based China Media Project, for her early input.

This MERICS Report is part of the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.