China Inc is recalibrating its approach to its overseas footprint as the BRI turns 10 years old

No. 3, September 2023

What you need to know

China Inc is recalibrating its approach to its overseas footprint as the BRI turns 10 years old

Sometime in October, Beijing will play host to the third Belt and Road Forum as Xi Jinping will celebrate the 10 year anniversary of his signature foreign policy agenda. As the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) enters its second decade, its newest projects are very different from the first wave of deals were – having shifted from massive scale traditional infrastructure undertakings that facilitated bulk and container logistics by rail and ship to more technologically advanced projects that transmit ones and zeroes via fiber optic cables and satellites. However, the context that the BRI began in, back when it was still called OBOR (One Belt One Road), couldn’t be more different than where it operates in 2023. Xi Jinping has profoundly changed China, and other countries have changed their stances on Beijing and how they interact with the party-state, for better or worse, from China’s own perspective. In that new ecosystem, we are seeing: changes to the BRI itself, a new and shifting ecosystem of regional trade agreements, and diverse strategies from Chinese firms going overseas.

In this edition, MERICS Analyst Francesca Ghiretti looks at the changing nature of the BRI and how it fits into the growing toolkit that Beijing is assembling for its strategies overseas. She finds that the BRI is shifting alongside China’s own shifting needs and capacities. The days of a torrent of mega project announcements under the BRI umbrella are long gone, but that doesn’t mean the initiative itself is fading away. Instead, it is becoming one of several tools in Xi’s foreign policy agenda, and increasingly, one more aligned with the higher value-added industries that China has solidified over the last decade. As Ghiretti argues, the Digital Silk Road will likely be the central pillar for the BRI moving forward, while it will also be tied in with fresher global initiatives coming out of Beijing.

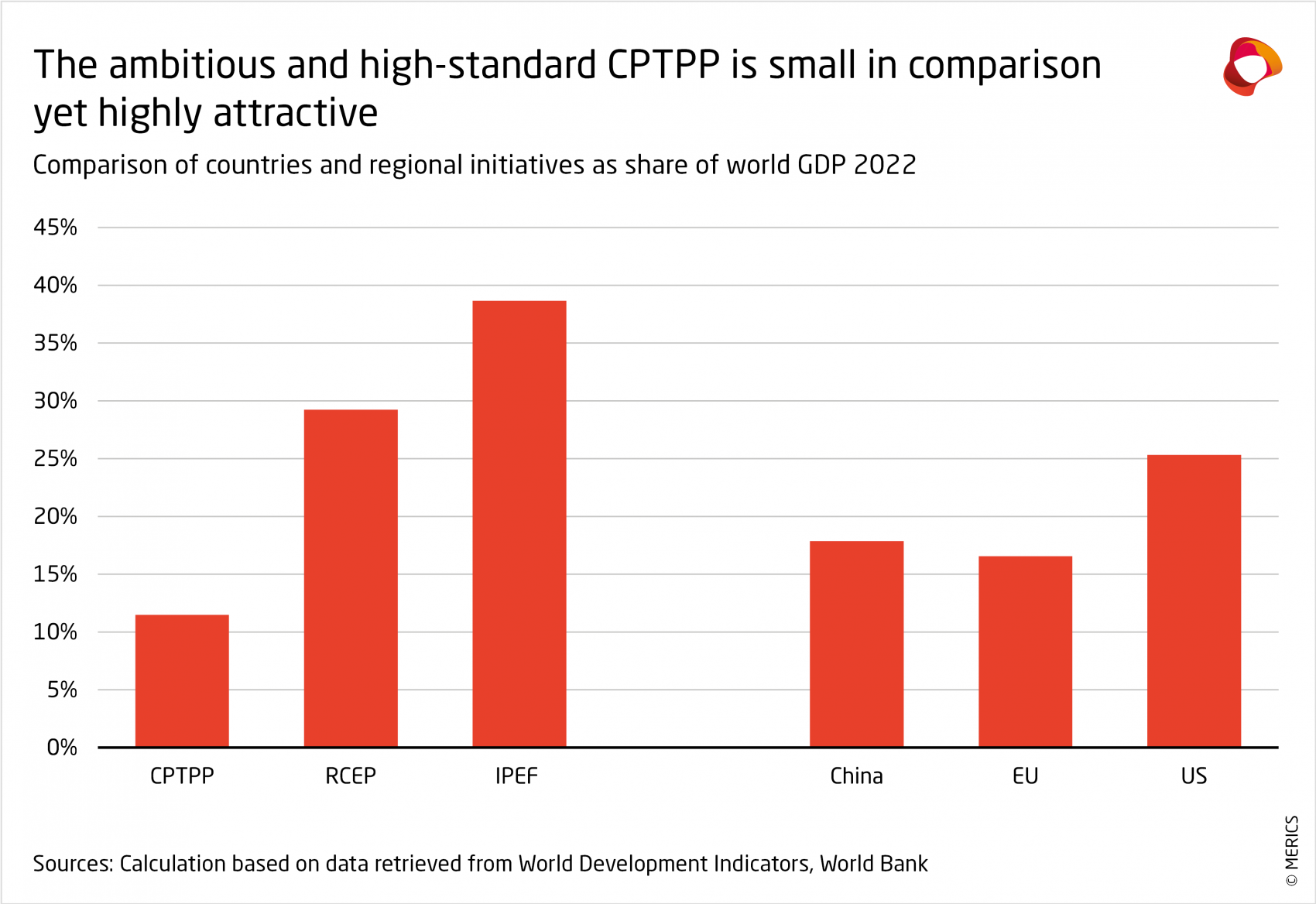

Meanwhile, MERICS Analyst Aya Adachi examines new developments in the overlapping regional trade deals that are stacking up in the Indo-Pacific. The strongest and most binding of those agreements, the Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) ironically is missing the two biggest markets of the region: the US and China, with the latter attempting a bid to join. On the other end of the spectrum, the recently developed and US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is more an agreement on principles and guidelines rather than anything binding. Finally, falling between is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a binding agreement solidifying trade systems across northeast and southeast Asia that lacks the deeper reform requirements that CPTPP demands. Finally, Adachi compares these three frameworks through a general lens, but also through a European one, as the EU remains by far the largest market outside of all three.

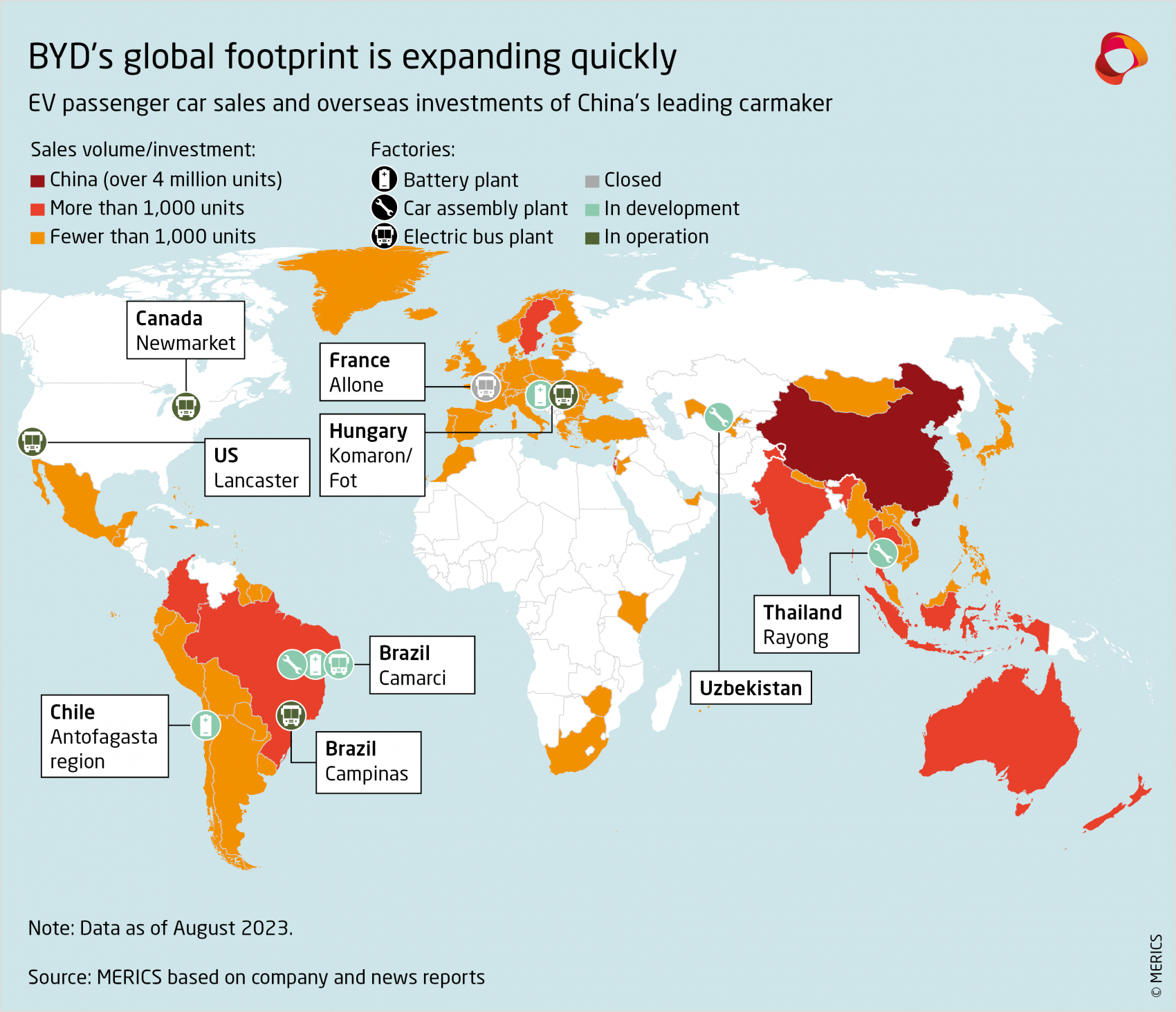

To wrap up this edition, MERICS Senior Analyst Jacob Gunter is joined by colleague MERICS Analyst Gregor Sebastian, who brings his automotive expertise to bear as the two explore how BYD, now China’s largest automaker and a global EV leader, is approaching its overseas expansion. The company has become a dominant player in China’s domestic EV scene, which remains the overwhelming focus of the company. However, BYD is increasingly looking abroad, both at export markets, and investment opportunities. It already found success in exporting and producing overseas in its EV bus line of business, giving it precious experience abroad. Interestingly, much of its investment strategy is focused on developing and middle-income markets – which could be easier to win market share in, but will also be, per capita, smaller prizes to win. However, despite BYD being courted by many governments to expand their operations in those markets, it is also running into headwinds, from scuttled opportunities in India to growing skepticism to Chinese EV exports in the US, all the way to a new investigation into Chinese EV exports to the EU. As Gunter and Sebastian argue, BYD is likely to become a major competitor to European car brands, perhaps eventually in their home market, but in the short term, in third markets.

Top Story

10 years on, the BRI’s future is small, beautiful and digital

The 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative in September prompted a stocktaking of how well the globe-spanning web of infrastructure, loans and relationship-building has performed and speculation about its future.

For some, Beijing’s recent spate of initiatives suggest the BRI belongs to China’s past, while the new initiatives are the future. They point to China-led multilateral projects launched since 2020, such as the Global Data Security Initiative (GDSI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI).

The argument that China is moving away from the BRI is strengthened by the rise in BRI debt defaults and a decline in infrastructure investment abroad by Chinese banks.

Debates about the BRI’s limitations or demise are not new. Endless questions about its the health and future stem partly from the difficulty of grasping what the BRI is and what it does. Ultimately, the BRI was, and still is, a framework to channel China’s home and foreign policy needs. As such, the means and focus often change. Since 2013, the BRI has undoubtedly maximized China’s influence and turned it into an economic partner throughout the developing world. However, China’s needs, and foreign policy of today are not those of China 10 years ago.

What remains consistent is that the BRI was added by Xi Jinping into the party Constitution and that China deploys it to foster strong bilateral relationship with third countries. These aim to secure supplies of resources, especially of critical raw materials; to open markets for its own companies; or to solidify friendships that can be used bilaterally and in multilateral fora. These aims are made more relevant than ever are by rising geopolitical friction.

Many things have changed in the last decade, most obviously the international landscape, which is marked by fiercer bilateral and global competition between the United States and China. Hence, Beijing feels more need to strengthen its many bilateral relationships and reinforce its position in multilateral bodies. They might be multilateral groups, such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, with strong links to Beijing, or wider fora that can be leveraged to provide outcomes favorable to China, such as the G20 and the various UN bodies.

The Digital Silk Road will see China’s digital champions take the lead in lieu of SOE megaprojects

China’s economy has also changed in the last ten years. The country’s economic slowdown means that large infrastructural projects can no longer be the basis for its interaction with third countries. This explains Xi’s new direction for the BRI, based on investment in “small and beautiful” projects. Enter the Digital Silk Road. Already in 2020, Wang Yi, China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, described the DSR as “a priority area for the BRI cooperation in the next stage”.

In that same speech, Wang Yi also spoke of a new initiative that fed into China’s DSR ambitions: “China has put forth the Global Initiative on Data Security designed to [..] promote collective efforts toward a cyberspace featuring peace, security, openness, and cooperation”.

Beijing’s promotion of GDSI has not been particularly strong, though it has picked up official support from Russia, Pakistan, Laos, the Arab League, ASEAN countries, SCO-members Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, plus Turkmenistan. However, Beijing’s interest in shaping standards for data security and digital commerce has not slackened. Multilaterally, China has pushed to promote its technologies and influence in standard setting bodies such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

Furthermore, Chinese investments in the DSR have not slowed either, if anything the opposite. Chinese companies are increasingly present in the digitalization of developing economies as Western alternatives are either absent or too costly. That was the case of 4G and 5G, where Huawei build 70 percent of Africa’s 4G network and had signed 5G agreements with Kenya, South Africa and Uganda by end-2022.

Another flagship DSR project is the 15,000 kilometer-long PEACE submarine cable, which connects Asia, Africa, and Europe (Singapore, Maldives, Seychelles, Pakistan, Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Cyprus, Tunisia, Malta and France).

Arguably, many of these investments are labelled as DSR artificially, after their establishment, or not at all, and they are carried out by private enterprises such as Huawei, ZTE or Huawei Marine (which became a unit of state-owned Hetong Group in 2020). Private companies, especially, CATL and Alibaba have dominated the foreign investment scene, while SOEs are still the main actors for construction contracts.

Much of the above has already been experienced with the more traditional BRI, so why should it be any different for the DSR? Anything that fits the objectives can be DSR. Nonetheless, it does seem that, rather than the DSR existing uniquely as a separate category, the focus on digital matters has taken on a transverse character, appearing as common theme in several initiatives, though most of all in the GDI. Furthermore, much like the BRI, the DSR seeks to produce vertical integration and home advantages in the Chinese market and then export abroad from a stronger position. The Chinese firms involved in the DSR have the resources and the profit motive to keep expanding, whereas others, especially SOEs, do not.

A digital GDI to advance China’s tech champions and promote China’s broader digital ecosystem

A 2023 progress report on the Global Development Initiative, published by China’s foreign ministry-linked Center for International Knowledge on Development (CIKD), lists digital economy and connectivity in the digital era among the main appraisal criteria for the GDI and its projects. They are mentioned alongside more traditional factors, such as poverty reduction, food security and development finance. To solidify the connection between this and the BRI, the term “small and beautiful” appears consistently in relation to the GDI projects reported in the document.

The “3S cooperation” - smart customs, smart borders, and smart connectivity – is present in bilateral and multilateral documents on collaborations under the GDI. According to the report, China has already signed 130 cooperation agreements in the framework of the 3S cooperation and the aim is that of lowering barriers in global markets. The cooperation’s scope covers “transforming the management structure from "compartmentalization" to "vertical and horizontal integration", from "working alone "to "multi-management", and from "experience-based management" to "data-driven management". If this integration is led by Chinese enterprises with Chinese software, for example, then China would have access to substantial amounts of data and could create disruption to systems if wished. It could also influence standards in the sector by becoming the main provider of such services.

Another example is the satellite that China launched on November 5, 2021, which has been branded Sustainable Development Science Satellite (SDGSAT1) with the explicit objective of serving sustainable development goals (SDGs). The satellite has shared more than 90,000 images of more than 70 countries and regions. Despite the mission’s positive branding, security questions remain about data collection by the Chinese, the safety of relying on Chinese data and the risk of interference if such satellites or their data are ever abused.

These are just two examples of how closely China’s initiatives interlink development, digitalization, and security.

The traditional BRI lives on, but is becoming more targeted

In 2022, the share of investments within the BRI, as opposed to construction contracts, reached 48 percent, its highest recorded level. The trend line showed the average value of BRI investment deals rising while construction agreements got smaller, reaching their lowest recorded average value in 2022. CATL investment in Hungary probably skewed the result in favor of investments, but the change in how BRI projects are financed was also because construction contracts have become more difficult to secure. They often rely on loans from Chinese banks which have become harder to obtain.

Looking at new projects by section, technology’s share is growing but energy and transport projects remain important. For example, in 2022, China Energy Engineering Corporation won the bid for a thermal power plant in Indonesia and PowerChina took on an Indonesian coal mining project. Mining and metals also ranked high in new BRI projects last year, in accordance with Beijing’s policy focus on raw material supplies.

BRI engagement in green energy has also been increasing, as seen in Saudi Arabia’s USD 210 million project with Jinko Solar and by PowerChina International’s part in building a wind farm in Laos for USD 1.5 billion.

More traditional areas such as railways and ports are attracting less interest. Existing projects continue (e.g., the Kunming-Singapore railway) but no new port projects were announced in 2022. Interestingly, the New Economic Corridor, the connectivity project launched by India and the EU during the G20 summit in Delhi in September, appears to be focusing mostly on those types of traditional connectivity projects. The ongoing interest in transport infrastructure demonstrates that traditional connectivity is still an attractive format to engage with third countries and a basis for economic development. Such an interest was already evident in other connectivity initiatives such as Build Back better world (B3W), the Global Partnership for Infrastructure and Investments, and the Global Gateway (although the latter has a wider focus).

The future of the BRI will adjust with both Beijing’s evolving goals and its changing capacities

All in all, the BRI’s future appears to be more digital, more security-driven and strongly focused on greater multilateral coordination with China. These points all align perfectly with China’s objectives, as set out in diverse strategic and policy documents. However, this does not mean more traditional BRI projects are dead.

The projects most likely to be exempted from the “small and beautiful” approach will be strategic infrastructure and resources projects, such as mining, oil and gas, according to a report by the Green Finance and Development Center, based at Fudan University in Shanghai.

The BRI’s new focus on the digital aspect will allow China to pursue its interest in being a technological leader and standard setter at a global level. At the same time, it suits the shift to “smaller and beautiful” projects that are less prone to large loan defaults. We can expect to see the digital dimensions of China’s foreign policy increase, regardless of whether it advances under the BRI label, or the GDI, or other initiatives.

Regional spotlight

CPTPP and IPEF: competing or complementary initiatives in the Indo-Pacific?

The Indo-Pacific region is undergoing ceaseless competition between different multilateral trade initiatives and groupings, so the EU needs to pay greater attention to the region if it wants to retain its influence and trade advantages in a shifting landscape. The latest trade pact to take shape is the US-led Indo Pacific Economic Framework(IPEF). Negotiations are due to conclude in November 2023. As neither China nor the EU are members, they will have to navigate any consequences from the sidelines.

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is a veil for limited US commitment

The Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) was launched by President Joe Biden in May 2022 on a visit to Tokyo. It is a dialogue platform for the United States and 13 other member countries to discuss key economic issues around the four pillars of (1) trade, (2) supply chains, (3) clean energy, decarbonization and infrastructure, (4) and tax and corruption. IPEF is widely thought of as a US project to compensate for its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) under President Donald Trump.

The IPEF is not a binding agreement. Rather, it is a suboptimal compromise grounded in the lack of US domestic support for trade agreements It was, and is, an attempt to swiftly carve out room to maneuver strategically, and address the vacuum left by the US withdrawal from TTP, without the need to ask Congress to approve a more substantial and binding deal.

Like other US-led fora, the IPEF also serves as a platform to promote dialogue around trade issues and to try compensating for the WTO stalemate to reform global trade rules and US blocking of appointments to the Appellate Body. Other fora with similar roles include the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP) between the United States and Latin America, and the US-EU Trade and Technology Council. All these fora seek to develop and promote rules and norms on various above-mentioned issues with the option to incorporate them into a formal multilateral or regional trade arrangement that includes the United States in the future.

The CPTPP has traction and appeal

After the United States quit the TPP, the remaining members regrouped and swiftly concluded the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP is recognized as an agreement that provides a strong and substantial detail in its coverage, ranging from stronger commitments to human rights, labor and environmental standards, intellectual property rights and procurement. It is a living and progressive agreement, designed to make regulatory adjustments in changing circumstances, while leaving the door open for any future US return. Despite its small size measured by combined GDP of its members, it has proved attractive (see chart). Candidate countries include South Korea, China, Taiwan, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Uruguay and Ukraine. The CPTPP concluded membership talks with the United Kingdom in July 2023. As the first case of accession, the negotiations with the UK set a high bar to fulfil high standards and substantial level of liberalization for other candidates, especially for China.

Commitment to binding ties is welcomed

There are overlaps between the IPEF’s pillars 1 and 3 which focus on trade, clean energy, decarbonization and CPTPP rules and standards on labor, environment, digital economy, agriculture, competition. But a strong difference is that IPEF will not generate any binding agreements anytime soon, nor will it include a dispute settlement process or treaty interpretation mechanism. Given these limitations, IPEF is unlikely to move beyond existing international obligations (such as those of the WTO or International Labor Organization (ILO)). IPEF will mainly serve as a mechanism for transparency, information sharing and coordination.

Many countries in the Indo-Pacific regard the IPEF as serving a different purpose to the CPTPP. IPEF allows members to be part of a conversation with the US that may have potential future implications. The CPTPP trade agreement is more attractive because it can leverage market access when creating formal, binding rules, especially rules to regulate competition. The growing interest in joining the agreement indicates the demand for formal arrangements in the region that offer new market opportunities and stability.

Given that CPTPP and IPEF widely differ in what they can deliver, countries consider them as complementary for navigating the Indo-Pacific. Seven CPTPP members – more than half – are also IPEF members and all of them are already linked to China via yet another grouping, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Overlapping regional initiatives are nothing new in a region that has witnessed a clustering of competing forums and trade agreements in the past 20 years. Countries in the region are accustomed to navigating competing initiatives and prefer to join multiple projects than choosing one over the other. As the competition over the creation of regional groupings has expanded from East Asia to the Asia-Pacific to the Indo Pacific this tendency towards pragmatism is likely to continue.

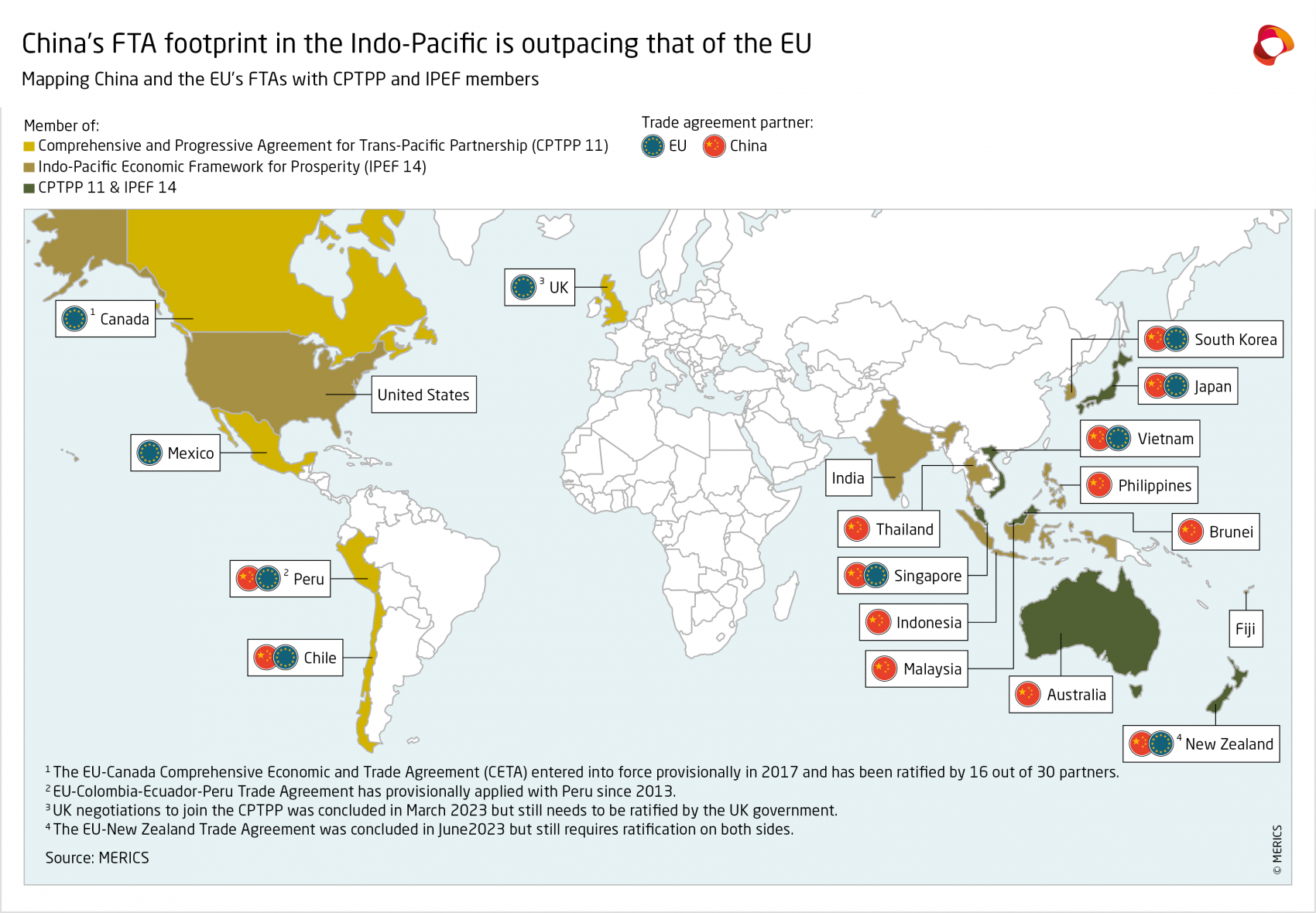

China’s FTA competitiveness in the Indo-Pacific is rising

China is an attractive Free Trade Agreement (FTA) partner as it is nominally world’s second largest economy and retains above average remaining 'most favored nation’ (MFN) tariff rates still to be reduced. China started negotiating trade agreements in the early 2000s and in recent years its ambition to use them as a key instrument to promote and diversify economic ties has grown. Beijing concluded RCEP in 2020, China’s most substantial regional agreement to date. Its decision to apply for CPTPP membership in 2021, drew attention to China’s commitments. Since then, China has implemented a series of unilateral liberalization measures to signal its willingness and fulfil some of the CPTPP membership requirements.

China is economically relatively well positioned in the Indo Pacific, despite its exclusion from IPEF and slim prospects joining CPTPP any time soon. Beijing has already concluded agreements with eight out of 11 CPTPP countries (excluding the soon-to-join United Kingdom). Chinese agreements typically focus on trade in goods, with few provisions on competition and procurement. They provide a low degree of liberalization and regulatory scope in services and investment.

In recent years, Beijing’s agreements have expanded their regional coverage. All countries that are members of both initiatives (the IPEF and CPTPP) are already linked to China through RCEP. China currently has an FTA with nine out of 14 IPEF members and is negotiating with two of the remaining five. Beijing is also renegotiating and updating its terms with ASEAN and has shown interest in a possible a trilateral agreement with Japan and South Korea. Latin American governments also favor making trade agreements and China is ready to negotiate with them, stepping into the gap left by limited US capacity and the EU’s slow and rigid responses.

Although China has a mixed track record on implementing the WTO accession protocol, it shows a willingness to bring offers to the table that the United States does not. Countries in the Indo-Pacific therefore do not see any downsides in signing agreements with China to better their access to the Chinese market.

The EU risks taking its position for granted in a volatile world

By contrast, the EU is on a weaker footing when it comes to forming economic pacts and frameworks in the Indo-Pacific. The EU has FTAs with seven out of 11 CPTPP countries, or eight out of 12 if the United Kingdom is included. Brussels is still in the process of negotiating its bilateral with Australia, but it signed an agreement with New Zealand in July this year that still needs to be ratified. The EU currently only has FTAs with four out of 14 IPEF members and is in talks with five of the remaining 10. Like the CPTPP, EU agreements provide a substantial degree of liberalization and include stronger coverage of so-called Non-Trade Issues, such as human rights, labor and environmental rights. The greater level of depth and substance have made it more difficult for the European Commission to negotiate agreements – as have the increasing and active concerns from EU member states about direct and substantial impact on their economies, the functioning of the single market, regulatory standards, and broader political and social considerations. The EU is trying to close the gap but it has been slow to achieve results. For instance, Malaysia and Brunei have yet to meaningfully negotiate an FTA with the EU.

The EU has been able to set global norms and standards, through its sheer size as the world’s largest market. Companies from various countries have an innate interest in complying with EU regulations and standards in order to gain market access. Non-EU countries that want to trade with the EU or EU-based companies often align their own regulations with EU standards to facilitate trade and investment – the so-called “Brussels effect”.

Yet the EU is facing a growing challenge within the Indo-Pacific region as China, the United States, and other countries engage in creating a competitive landscape of free trade agreements. Although the EU's regulations and standards remain significant, the emerging economic dynamics of the Indo-Pacific present alternatives for countries seeking trade partnerships. This competition not only dilutes the EU's impact but also underscores the importance of proactive engagement from the EU to ensure its regulatory power retains its global reach amidst the evolving trade dynamics in the Indo-Pacific.

Key Player

BYD’s international expansion challenges legacy carmakers in third markets

The EU’s decision to launch an anti-subsidy investigation into electric vehicles (EVs) coming from China shows how fast Chinese EV exports are growing. Announcing the inquiry in her annual ‘State of the Union’ speech, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen compared the rapid spread of Made-in-China EVs, which have taken eight percent of European EV market in the last year, to the solar sector. She promised not to allow a repeat of how “China’s unfair trade practices” affected that industry.

For now, most Made-in-China EVs sold in Europe are Western brands like MG or Tesla, but Chinese brands are quickly ramping up exports to the continent. One of those homegrown EV champions is BYD. Earlier this year BYD overtook Volkswagen as the best-selling carmaker in China. But the Chinese EV producer is not content with pole position in China’s domestic market. BYD is also looking to sell passenger EVs internationally, leveraging its domestic gains in China, the world’s leading EV market. For now, most of BYD’s exports have gone to emerging markets but Europe is in the company’s sights. BYD debuted six EV models for the European market in early September at Europe’s largest automotive road show, the IAA in Munich.

BYD’s international expansion will have considerable global impact. It took BYD 13 years to produce its first million NEVs - from 2008 to 2021. Production quickly accelerated, with the automaker celebrating as its five-millionth car rolled off the production line in August 2023.

As with the meteoric rise of Toyota during the late 1960s and 70s, the ascent of BYD is raising alarm at the headquarters of legacy carmakers and EV incumbents like Tesla. Given the automotive industry’s importance to GDP in advanced economies, governments will also feel the results if well-established brands are left behind in the EV race or lose market share.

BYD’s already sizeable global footprint is growing

BYD was founded as a rechargeable battery company by chemist Wang Chuanfu in 1995. Unlike many of its Chinese counterparts, BYD is not a state-owned enterprise (SOE). It listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2002, and won the backing of star stock-picker Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway fund in 2008.

BYD was already one of the world’s largest phone battery makers when, in 2002, it diversified into the car market by buying Tsinchuan Automobile. BYD’s battery expertise meant it could leverage in-house know-how whereas other carmakers had to rely on external suppliers like CATL or Panasonic. In fact, BYD was the first large carmaker to fully phase out its ICE vehicle lineup, committing itself to a NEV-only strategy ahead of all except fellow new-comers like Tesla, Nio or Xpeng – a move that probably positioned it well in the policy ecosystem.

Through the 2000s and into the 2010s, BYD Auto predominantly produced and sold in China, with one exception: electric buses. BYD’s battery powered buses became the focus of its first international sales push. It became the world leader by sales in 2015, with overseas production plants in the United States, Canada, Brazil and Hungary. It has sold more than 70,000 EV buses.

This early success provided a strong foundation for BYD's new international push, centered on passenger-vehicles. So far, BYD has not exported all that many EVs (see exhibit 1). However, it is debuting its vehicles internationally, rapidly scaling up EV exports, and had managed to become China’s largest EV exporter in August eclipsing frontrunners Tesla and SAIC.

BYD’s EV export destinations differ from China’s overall EV exports led by SAIC and Tesla, which have mainly gone to Europe. Instead, BYD has focused on emerging markets where competition from legacy carmakers is less entrenched, particularly Latin America and Southeast Asia. The aim is to establish a foothold in nascent growth markets, where an early push could cement BYD’s local market share. BYD is also establishing a local manufacturing presence in these markets to cater better to local demand and protect against any political backlash (see map).

A key element of BYD's penetration strategy has been to enter new markets in partnership with car rental companies, taxi operators, and ride-sharing platforms; for instance, its deal to provide 100,000 EVs by 2028 to European car rental company Sixt. This allows consumers to become familiar with the BYD brand in a low-cost, low-commitment way. BYD has also reportedly offered dealerships a higher share of sale premiums, potentially incentivizing them to give a lot of space to BYD vehicles, and even to promote its cars over those of competitors.

However, BYD's international expansion has not been without challenges. In India, for example, a EUR 922 million (USD 1 billion) proposal for BYD and a local partner to build an EV production plant was rejected over security concerns. The refusal highlights the geopolitical hurdles that BYD could face to its expansion into certain markets.

BYD’s outward push is motivated by economic and political factors: BYD is looking for fresh customers as its home EV market will soon be saturated

Although BYD has secured a significant share of China's thriving EV market, its domestic growth trajectory may slacken as competition increases from established players like Volkswagen and newcomers like Xiaomi. BYD is therefore positioning itself as a trailblazer in overseas markets. It is targeting countries like Brazil, Indonesia, and Thailand, (whose collective populations exceed the EU’s by some 110 million), where lack of charging infrastructure means EVs are a fraction of total passenger vehicle sales. Its proactive, long-term vision could give BYD a competitive edge over foreign incumbents but to succeed the company will need to invest in local charging infrastructure or convince politicians to invest in the technology.

Furthermore, BYD's growing production capacity will need a global outlet. Unlike some Chinese carmakers, who suffer underutilization, BYD maintains a robust production capacity that exceeded 90 percent utilization in early 2023. However, despite a hefty backlog of 700,000- vehicle orders in mid-2022 from high domestic sales, BYD could soon run into overcapacity as it ramps up output. Zheshang Securities predicts BYD's 2023 production capacity in China could reach 4.3 million units, eclipsing domestic sales (1.26 million units in H1 2023). Exports would then become a necessity for returns on investment.

BYD is securing overseas supplies of critical materials

BYD also differs from other EV producers in terms of its deep vertical integration. It already makes its own batteries and chips, which it sells to other companies, and aims to expand its influence by directly sourcing raw materials overseas. BYD is negotiating the purchase of up to six African lithium mines, which could supply battery material for around 27 million EVs. In Chile, it has secured favorable prices for lithium carbonate in exchange for local lithium processing. Gaining access to crucial raw materials could significantly enhance BYD's long-term business prospects, particularly as China's own lithium resources are insufficient to meet both domestic and global demand.

BYD is aligning its corporate strategy with Beijing’s strategic priorities

BYD wants to align its corporate strategy with Beijing’s policy priorities. China’s government has been striving to elevate its domestic carmakers onto the global stage ever since it overtook the United States as the largest automotive market and producer in 2009. This policy objective was explicitly outlined in China’s 2017 blueprint for the automotive industry, the Mid- to Long-term Automotive Industry Development Plan. Chinese EV brands are meant to rank among the world's top ten carmakers by 2025. For BYD, therefore, EV exports and FDI make commercial sense while also helping to win favor with top policy makers. In addition, Beijing has recently stressed the private sector needs to be closely aligned with national priorities.

Foreign leaders court BYD for direct investment

BYD is keen on nurturing ties with host nations and tapping into local subsidies which are often tied to local production – and many foreign governments are equally keen to attract BYD. Foreign government officials have actively courted BYD. Figures like Bruno de Le Maire, France's Minister of Economy and Finance, Luhut Panjaitan, Indonesia's Coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs and Natural Resources, and officials from Algeria and Morocco, have met BYD on visits to China. Even in Brazil, which offers few EV incentives, President Lula da Silva courted BYD, hoping to "jumpstart" a defunct Ford factory. With the promise of Brazilian subsidies, BYD has announced that it will invest EUR 570 million to upgrade the former Ford plant. BYD's investment pathways have been paved by diplomatic courtship and backed by perks such as Chile’s affordable lithium processing resources or Brazilian subsidies.

However, in this intricate dance, some are also ready to tread on toes. Foreign leaders might use regulatory cudgels to nudge BYD towards overseas investment. The EU Commission’s investigation, announced on September 15, could result in anti-dumping tariffs on Made-in-China EVs if they are found to have benefitted from subsidies. The EU inquiry puts BYD's exports to the region at risk, which may pressure it to prioritize European investment. Meanwhile, BYD dropped its plans for localizing production in India after the local authorities scrutinized the investment based on national security concerns. BYD is clearly taking notes from history. The cautionary tale of Japan's export-only approach illustrates the importance of building alliances beyond China’s borders.

BYD’s biggest impact is likely to be on third-market’s rather than the EU, at least for now

Although China’s EV industry is investing heavily in the European EV ecosystem, much of it is upstream in products such as EV batteries. When it comes to EVs, advanced economies will likely be shielded to some degree by brand loyalty in affluent regions where more consumers can afford it (brand loyalty is higher in Germany, the United States, and Japan than in China, for example). Lack of familiarity with BYD and other Chinese EV-makers will also help incumbent brands – though climate-conscious younger consumers may be quicker to be convinced, especially if Chinese EV brands prove highly cost competitive.

Aware of the challenges of breaking into European markets, BYD has prioritized its investments in emerging markets. Many developing countries are eager to court BYD, and Chinese EV investment more broadly. They have more to gain than a BYD plant. The richer prize would be a localized supply chain of OEM plants producing components for end-user automakers. Such a process would see Chinese firms doing what European automotive investment once did for China. If BYD sticks to its current strategy, European automakers can expect a tougher challenge in third market competition, and a greater one there than in their home market.

If BYD were to invest heavily in production in Europe, it could bring both benefits and drawbacks to the common market. Obviously, greenfield investment could generate new jobs and help to localize more of China’s competitive EV technology chains. If BYD integrates into the local supplier ecosystem, it could boost demand for European auto component makers, thereby generating new jobs. Unfortunately, this kind of job-creation seems unlikely. BYD’s value chain can be highly vertical – over 80 percent of suppliers for the Han model of the Dynasty line are Chinese, and half of them are BYD subsidiaries. This suggests that BYD might not integrate much with local suppliers. If the bulk of BYD’s components were to be shipped in from China, any success it might enjoy in Europe would likely be negative for European auto component makers and European workers.

Furthermore, while competition is natural – after all, European automakers have long competed in China, so it is only sensible that Chinese automakers might compete in Europe – greater involvement by BYD in Europe down the road could help import Chinese distortions into the common market. BYD openly states that it benefitted from extensive government grants and subsidies in China. Added to that is the below market, and sometimes interest free, financing that BYD has enjoyed, especially from local governments in China eager to attract BYD’s investment. Much of that support has diminished over time, though hardly all of it. In that sense, BYD may be able to project some home market advantages into European markets by lowering margins to build market share, which, if done so by offsetting those lost profits through anti-competitive support in China, would be a market distortion in the EU.

BYD’s success is not guaranteed

BYD’s rise as China’s biggest carmaker, coupled with its focus on overseas expansion, is a threat to the profitability of legacy carmakers in Europe, East Asia and North America. Companies need to be aware that their bottom line is at risk, and not just in China, or their home market, but in important third markets. For instance, Brazil is Latin America’s biggest car market. The combined market share of US and European carmakers Stellantis, GM and Volkswagen there is 62 percent.

However, BYD’s global expansion is not without risks. For instance, many of the emerging markets targeted in BYD’s internationalization efforts lack high consumer demand for EVs. BYD risks seeing its investments in countries like Brazil or Thailand become unprofitable. Such setbacks could stall BYD’s global expansion - or make the automaker even more reliant on Beijing’s helping hand.

Global China Inc. Updates

China Inc.’s political and diplomatic developments /BRI

President Xi forges closer bonds with Central Asian countries

China and Pakistan have signed six agreements and MOUs to solidify their bilateral ties at a ceremony attended by Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng. The agreements range across the economy, from the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), to transport links and the export of dried chilies. China has recently doubled down on lending to Pakistan, overlooking frictions over its loans, and recently helped it to unlock a USD 3 billion IMF bailout that had been on hold since December 2022. Beijing's commitment to the CPEC underscores its strategic view of Pakistan as a key gateway to the Indian Ocean, avoiding contested maritime chokepoints in Southeast Asia.

Egypt’s Suez Canal attracts billions in Chinese investment

Egypt has finalized investment agreements with Chinese firms totaling more than USD 8 billion for its Suez Canal Economic Zone in recent months. The zone now contains six ports and four industrial estates, including the BRI-project Teda City, a 7-kilometer square manufacturing hub. Beijing sees the Suez Canal as a “critical maritime conduit” for the Maritime Silk Road due to its strategic importance to global trade. The recent deals include a USD 1.5 billion commitment to build a green hydrogen plant by state-owned China Energy Engineering Corporation. Plans are also underway for a USD 2 billion cast iron pipe facility and a USD 310 million plant making bromine and caustic soda.

Digital, Health, and Technology

China flexes its extra-territorial muscle to block Intel’s acquisition of Tower Semiconductor

Intel has terminated its USD 5.4 billion acquisition of Israeli foundry Tower Semiconductor after failing to secure regulatory approval from China’s antitrust regulator. Neither company is Chinese, yet China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) authorizes mergers or acquisitions of companies with a large China presence. Intel has a substantial market and several factories in China. The case highlights the complexities of global business amid China-US tensions. SAMR’s review authority over global M&As is one of the few tools in the field of advanced chip technologies that Beijing could use to retaliate against US export restrictions.

GPS rival Beidou goes global with Alibaba’s Amap

Alibaba's mapping service, Amap, has expanded its global coverage using China's indigenous Beidou satellite navigation system, which is China’s alternative to the US GPS system. Amap now supports route planning and navigation in over 200 countries and regions. The expansion of Amap (known as Gaode Map in China) was made possible by an upgrade on September 2, leveraging the Beidou system. Amap's CEO, Liu Zhenfei, announced the expansion at a BRI event, saying Amap will “actively participate” in the digitization of Beijing’s global infrastructure connectivity plan. In May, China launched its 56th Beidou satellite. The GPS fleet consists of 24 satellites.

Energy, Resources, and Commodities

Chinese company begins construction of USD 700 million lithium plant

China's Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt has commissioned a lithium concentrator to refine lithium in Zimbabwe, further solidifying Beijing’s lead in lithium refining and processing. Huayou bought the Arcadia hard rock deposit for USD 422 million in April 2022 and has now followed up with an additional USD 300 million to build a refinement facility able to produce 450,000 metric tons of lithium concentrates a year. In the last two years, Zimbabwe’s lithium sector has received more than USD 1 billion from Chinese companies such as Huayou, Sinomine Resource Group, Chengxin Lithium Group, Yahua Group, and Canmax Technologies. Zimbabwe’s government, in turn, wants to move up the value chain by incentivizing the local processing of concentrates into battery-grade lithium, though the commercial viability of localization remains unproven.

Pakistan to build a Chinese-designed USD 3.5 billion nuclear energy project

Last July, Pakistan's Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif approved the construction of a USD 3.5 billion, 1,200-megawatt (MW) Chinese-designed nuclear energy project. The plant will be built in eastern Punjab, using a Hualong One, a third-generation reactor designed by China’s National Nuclear Corporation. The site already hosts four other Chinese nuclear facilities. Pakistan gets only 8 percent of its electricity from nuclear energy but plans to get 20 percent by 2030. French and US firms, have lost market leadership as Chinese and Russian designs now make up 80 percent of new reactors under construction since 2017, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. Western nations have faced significant cost overruns and delays when re-igniting their nuclear industries, casting doubts on their companies’ competitiveness against Chinese firms.

Chinese-backed energy project in Lesotho points to a shift in BRI strategy

Lesotho’s Mafeteng Solar Power Plant has begun generating 30MW of electricity, enough to power 30,000 homes. The Mafeteng plant will reduce Lesothos’ dependence on expensive imported power and improve access to electricity across the country. The project typifies Beijing’s evolving "small is beautiful" approach to African infrastructure as it switches to smaller, more debt-sustainable projects. This pivot reflects a conscious move towards safer investments, and away from previous overreaches amid the debt challenges confronting both African nations and Chinese developers. The solar plant also underscores China's growing commitment to green energy within the BRI.

Volkswagen-backed Gotion High-Tech to open battery plant in Illinois

Chinese EV battery manufacturer Gotion has chosen Illinois for its new USD 2 billion EV lithium battery plant, as state governor JB Pritzker announced on September 8. The plant will benefit from a USD 536 million incentives packages linked to the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act. It is expected to generate 2,600 jobs and to start production in 2024. Chinese FDI into the US has been falling. However, the plant could still face a backlash similar to the one that sank Ford’s battery deal with CATL. Gotion, based in Hefei, is part-owned by Volkswagen and is rapidly expanding overseas. The company is building Vietnam’s first LFP gigafactory and is also looking at opportunities in Morocco and Thailand.

Manufacturing and Construction

China’s Baosteel invests USD 437 million in a ‘green steel’ joint project with Saudi Aramco and the Saudi Public Investment Fund

China's Baosteel is partnering with Saudi Aramco and Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), to build a "green steel" plant there. Baosteel will invest USD 437.5 million for a 50 percent stake. The aim is to make the world’s “most competitive low-carbon emission steel.” The deal comes five months after a Saudi Aramco-Sinopec agreement to build an oil refinery and petrochemical plant in China’s Fujian province. China's BRI strategy is a good fit for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's 'Vision 2030' to diversify the Saudi economy. China is emerging as a pivotal enabler of 'Vision 2030', providing technical know-how and offering the Saudis an alternative to the United States.

China is winning a third of infrastructure contracts in Africa, new report finds

A new report by the Hinrich Foundation has found Chinese companies now account for a third of infrastructure investments into Africa, more than double the share of projects going to Western companies. In the 1990s, US and European companies were winning 85 percent of African construction contracts. The BRI has been central to this story. According to the Green Finance and Development Centre at Fudan University, more than USD 1 trillion globally has been channeled through the BRI.

Trade and Finance

Renminbi achieves milestone in internationalization drive

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) announced last July that the renminbi's share of global payments had surpassed 3 percent for the first time. The currency now ranks as the fifth biggest for foreign reserves, payments, and transactions, and the third largest for trade financing. PBoC spokesperson Jin Zhongxia said that the renminbi is making “steady progress” at enhancing its status as an international currency. The announcement comes after a resurgence of the debate about the renminbi’s potential to upend so-called ‘dollar hegemony’. However, the US dollar still accounts for 60 percent of global reserves – dwarfing the renminbi’s 2.5 percent. While Beijing will celebrate these milestones, fully displacing the US dollar would require deep financial and monetary reforms.

Zambia and China agree to a USD 4 billion debt restructuring after years of negotiation

Zambia has finalized a landmark agreement with China and other major creditors to restructure USD 6.3 billion in loans, including USD 4.1 billion owed to China. The deal, reached under the G20 Common Framework, does not involve debt write-offs, which China opposed. Instead, it extends repayment timelines and introduces a 3-year grace period. The restructuring aims to provide financial relief to copper-rich Zambia and is seen as a precedent-setting move towards longer-term debt sustainability. The issue of debt relief is becoming increasingly important as creditor nations recalibrate their economic engagement strategy with the Global South amidst great power competition.

China Development Bank to finance Nigerian rail project

Nigeria's Senate has approved China Development Bank (CDB) as the new financier for the Kaduna-to-Kano rail project, at a cost of USD 973 million. In 2020, China's Exim Bank withdrew from the project, voicing concerns about Nigeria's creditworthiness. Nigeria sought financial partnerships with Standard Chartered and other European entities before finally returning to Chinese banks. CCECC, the Chinese engineering company carrying out much of the railroad’s construction, ultimately brokered the deal to bring CDB on board. Analysts suggest the loan terms will be tougher than before as Chinese state-owned banks are putting commercial considerations first and are increasingly risk averse.

Transport and Logistics

China-backed Indonesian railway is ready for launch after 4 years of delays

Premier Li Qiang, in Indonesia for the ASEAN Summit, took a test ride on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway earlier in September. The line is finally due to go into commercial operation on October 1, after four years of delays. The high-speed rail link was a flagship project for both the BRI and President Joko Widodo’s modernization plans. However, the construction has faced multiple land disputes, accidents, Covid-related delays and a total USD 3 billion cost overrun. In 2019, Widodo also deal a blow to the rail link’s commercial viability with his announcement the capital city would relocate from Jakarta to purpose built Nusantra on the island of Borneo.

Central Asian land corridor to connect China and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan

In July China inaugurated a 3,125 kilometer land corridor with Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. The route connects Gansu province with Xinjiang by rail, then goes by road through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to Haritan, a town on the Afghan border. While the trade route’s commercial potential of is modest, it is symbolic of China’s desire to foster a working and pragmatic relationship with the Taliban regime. Although it has not formally recognized Taliban rule, it has appointed a chargé d'affaires and was the first country to send a foreign policy chief, Wang Yi, to Kabul. As Russia’s influence has waned, China has sought to enhance its presence in Central Asia and has long pushed for a rail link to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.