China offers its partners economic lifelines and diplomatic cover – not military guarantees

Crises in Venezuela and Iran have shown the limits of Beijing’s support. But Eva Seiwert argues that relations with Moscow show that non-military backing can still be crucial. This analysis is part of the China-Russia Dashboard.

Beijing’s hands-off approach to recent crises in Venezuela and Iran has thrown a stark light on bilateral partnerships with China. What is the value of closely aligning with Beijing if China will not prevent regimes being threatened or even toppled? In this context, China-Russia relations since Moscow declared all-out war on Ukraine in 2022 are particularly instructive: Even when China withholds overt military support for a country declared a close partner, the government of that country can still derive tangible – even if often less visible – benefits.

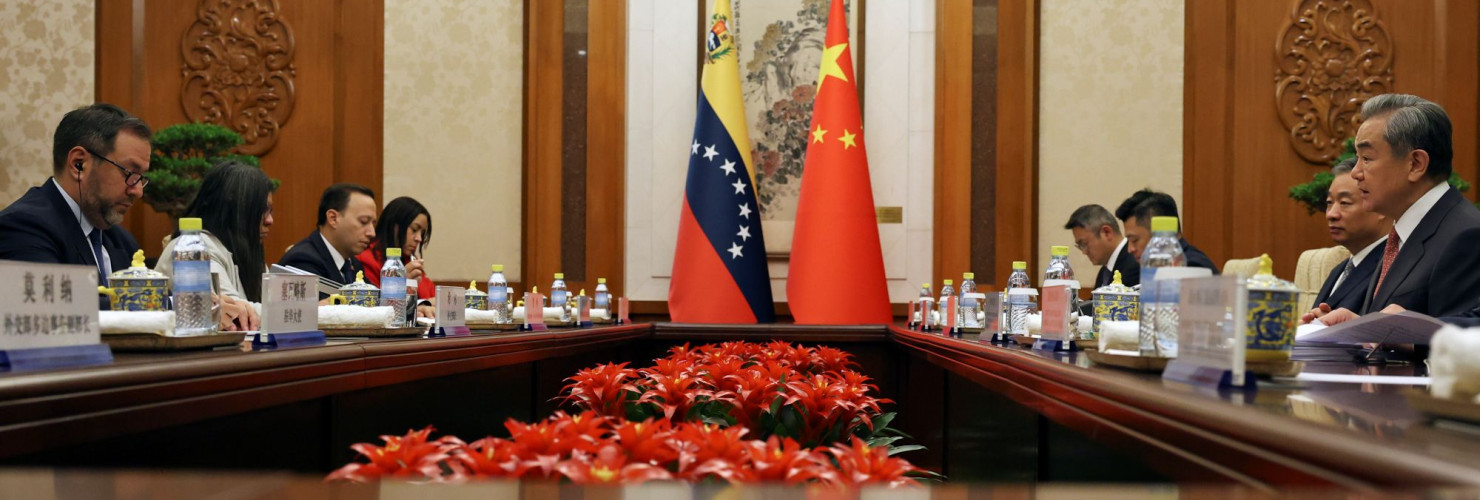

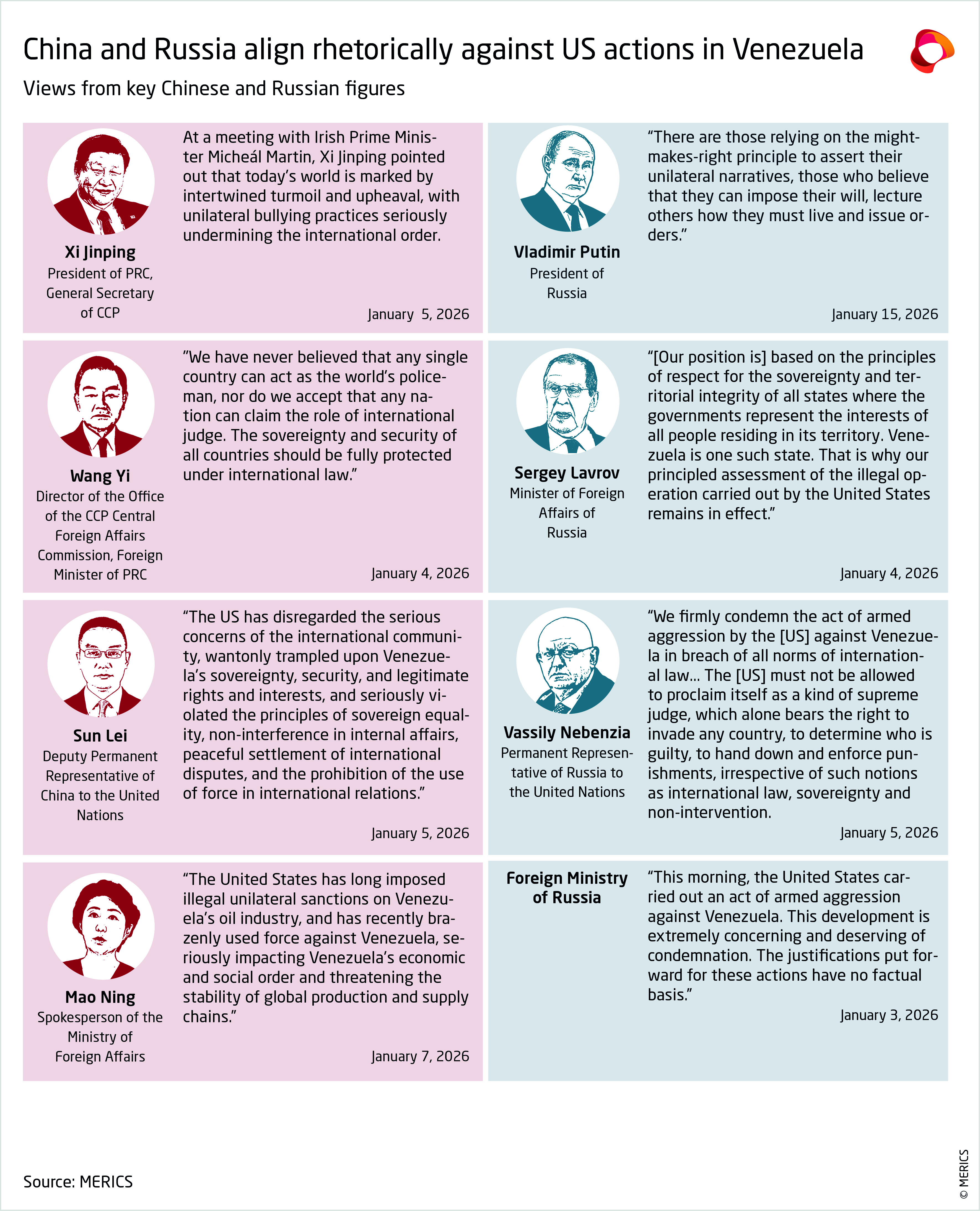

China’s reaction to events in Venezuela and Iran at first glance would appear to contradict this assessment. Beijing issued strong words of condemnation after the United States on January 3 captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. But it refrained from any further moves to help only weeks after China’s leader Xi Jinping had described China and Venezuela as “intimate friends, dear brothers, and good partners” – and pledged Beijing’s continued support for Venezuela’s sovereignty, national security and social stability.

Tehran has similarly received little more than verbal backing from Beijing in the face of mounting pressure. Following Israeli air strikes on Iranian targets mid 2025, Xi called on “major countries that have special influence on parties to the conflict” to de-escalate the situation.

Since then, Beijing’s “comprehensive strategic partner” has been shaken by renewed domestic unrest and threats of US military intervention. Yet China’s position – rhetorical opposition to external interference, short of concrete action – appears unchanged.

Partnership with China can be indispensable - even without overt military backing

But recent data from the China-Russia Dashboard shows that partnership with China can be indispensable, even without overt military backing. China now accounts for more than 40 percent of Russia’s oil exports and is the main supplier of high priority dual-use goods needed for Russia’s war effort. Over 99 percent of bilateral trade was denominated in yuan or roubles in 2025 – providing Russia with an economic lifeline, cushioning the impact of Western dollar-centered sanctions, and allowing the Kremlin to sustain its war.

Similar economic backing also makes China’s partnerships with Venezuela and Iran look less hollow than they first appear. Despite the US tightening sanctions against Tehran in 2018 and Caracas in 2019, China has been the dominant buyer of both countries’ oil. Chinese buyers have in peak periods taken up to 75 percent of Venezuela’s oil exports and an estimated 80 percent of Iran’s. While these shipments account for only a modest share of China’s total imports, they provide both exporting countries with critical revenues.

China’s role as investor and lender only reinforces this economic support. Venezuela has received an estimated USD 60 billion in Chinese loans over the past decades, making it one of the largest recipients of Chinese financing worldwide. Iran, meanwhile, signed a 25 year cooperation agreement with China in 2021, which referenced potential Chinese investments worth up to USD 400 billion. While realized investment so far appears to amount to only a fraction of that figure, the political signal of Chinese economic commitment still matters.

China also offers international legitimacy

China also offers something less tangible – but no less important – than money: international legitimacy. Xi and Vladimir Putin were guests of honor at each other’s commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in 2025 – both have interacted 19 times through in-person meetings or phone calls since Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine. Lastly, as the keystone of BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China also provides Moscow with platforms to present itself as a co leader of multilateral groupings that are gaining traction in the Global South.

Iran has benefited from similar, albeit less pronounced, forms of diplomatic inclusion. Against the backdrop of renewed confrontation with the United States, China supported Iran’s accession to the SCO in 2023 and BRICS in 2024. Additionally, BRICS and SCO members in 2025 issued joint statements condemning US-backed Israeli air strikes against Iran. These moves helped Tehran signal that it was by no means isolated in the face of external pressure and underscored China’s growing role in providing it with international political cover.

Venezuela, while not a member of BRICS or the SCO, has also received consistent rhetorical backing. At the UN Security Council emergency meeting following Maduro’s capture by the US military, China’s ambassador was one of Washington’s most outspoken critics. The Chinese foreign ministry has emphasized that Beijing will continue to stand by Venezuela “no matter how the political situation evolves”. Such declarations signal Beijing’s international support and help legitimize the government at a moment of extreme vulnerability.

China’s support of these countries is not altruistic. It benefits from relationships in which it can dictate terms, secure cheap resources and present itself as the tip of a movement against US dominance. Even so, the three cases show that evaluating China’s partnerships on military or crisis intervention alone obscures their function. They do not mirror US alliances or security guarantees. Beijing offers steady, long-term forms of backing – economic, diplomatic, and political – that help partners withstand pressure and maintain continuity.

This analysis is part of the China-Russia Dashboard, a collaborative research effort of the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), MERICS, and the Swedish National China Centre (NKK) and Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS) at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI). Explore the project here.