China-Russia alignment – a shared vision, without fully seeing eye to eye

Despite growing alignment between China and Russia, the countries’ self-proclaimed "no-limits partnership" does have limits, says Claus Soong in his analysis for the China-Russia Dashboard. They emerge when Beijing needs to address the evolving geopolitical situation.

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping announced their no-limits partnership on February 4, 2022, three weeks before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and since then China and Russia have noticeably strengthened their ties in key areas. However, the countries’ self-proclaimed "no-limits partnership" does have limits, which emerge when Beijing needs to address the evolving geopolitical situation. There are also fields in which Beijing is adopting a stance distinct to that of Moscow – a reminder that their shared antipathy to the West and its global influence makes them aligned, but not formally allied.

The MERICS-OSW-UI China-Russia Dashboard shows the growing economic alignment between China and Russia. Bilateral trade reached a record USD 245 billion in 2024, 66 percent more than in 2021, a year before the start of the war, driven in part by a surge in Chinese exports of civil-military dual-use goods like computer and telecoms equipment – and, increasingly, advanced machine tools and chip-making equipment. Chinese imports of Russian crude oil hit a record USD 62.26 billion, 54 percent higher than 2021, a year before when the US, EU and other G7 countries sanctioned Russian oil exports. Close to 40 percent of Russia’s international trade is now denominated in Chinese Yuan, up from 2 percent in January 2022.

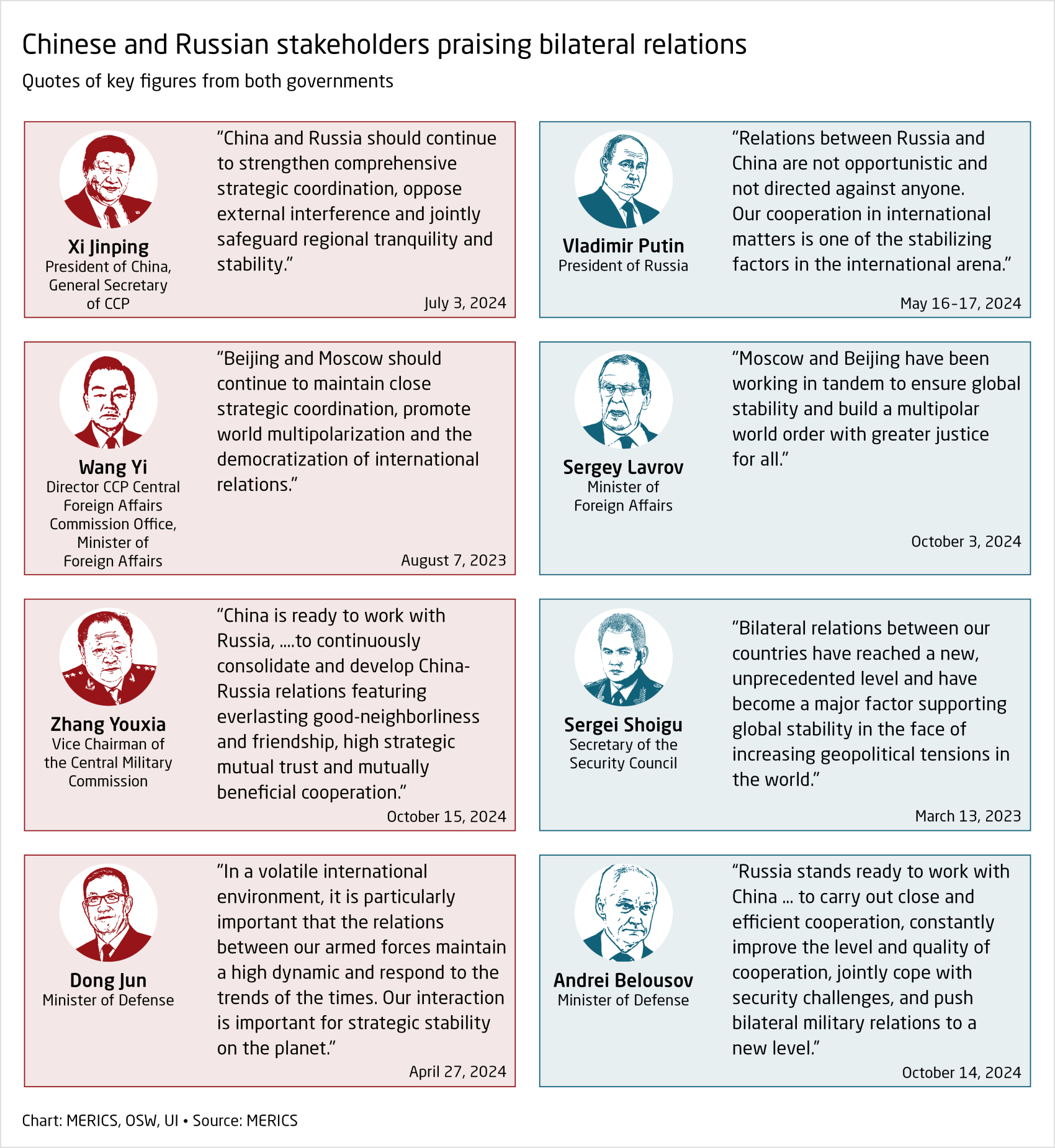

The frequency of high-level exchanges has surpassed that of any other bilateral relationship for both China and Russia

Border checkpoints between China and Russia have also become much busier since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There has been notable progress in expanding capacity, such as the construction of bridges across the Amur River and additional checkpoint facilities. This shift suggests that Moscow is putting aside concerns about China's growing influence in the sparsely populated Russian Far East in order to strengthen ties. Politically, the frequency of high-level exchanges has surpassed that of any other bilateral relationship for both China and Russia – Xi and Putin met or spoke by phone ten times between February 2022 and February 2025, and their foreign ministers spoke or met close to a monthly basis.

Amid this wealth of data pointing to a growing alignment between China and Russia, the Dashboard reveals one intriguing case of receding alignment – the United Nations. While both countries voted the same way in the UN Security Council 96 per cent of the time in 2018, their full alignment dropped to 83 per cent in 2024, as one country abstained from taking a clear position on the issue at hand. The receding alignment is even more visible in the General Assembly: its full alignment dropped from 77 per cent in 2018 to 67 per cent in 2024, with Russia and China taking opposing positions in about one in ten UN plenary votes.

The divergence in the General Assembly has been particularly noticeable with regard to the war in Ukraine. Between 2018 and February 2025, there were 21 votes in the General Assembly and Security Council on resolutions with “Ukraine” explicitly mentioned in the title, revealing a clearer trend of decreasing alignment between China and Russia in their voting behavior. Of the 8 votes on Ukraine from 2018 to 2021, China abstained only once, while in the remaining 7 instances, both China and Russia voted against the resolutions. However, China's tendency to abstain on Ukraine-related issues has increased significantly since the war began. From February 2022 to February 2025, there were 11 votes in the General Assembly and 2 in the Security Council concerning Ukraine, and China abstained in 8 of these 13 votes, including one in Security Council.

The “no-limits” partnership clearly has limits that are shaped by shifting geopolitical realities

Moreover, the interpretation of the so-called “no-limits” partnership changed over time showing the limits exist when there is a need to address the external geopolitical environment. In March 2022, Qin Gang, then Chinese Ambassador to the United States, stated that while there are indeed no “forbidden” areas of cooperation between China and Russia, there are clear bottom lines in the partnership—namely, “the principles of the UN Charter, the universally recognized norms of international law, and the fundamental guidelines for international relations.” In an interview in April 2023, Fu Cong, then Chinese Ambassador to the EU, described the “no-limits partnership” as “nothing but rhetoric,” emphasizing that China was not on Russia’s side in the war in Ukraine. Despite this, on the third anniversary of Russia's invasion—and shortly after Donald Trump held a call with Putin pushing for a deal to end the war—Xi Jinping reaffirmed the no-limits partnership between China and Russia.

Despite these reservations about full alignment with Russia, Beijing for now continues to view Moscow as an indispensable strategic partner. In China’s broader geopolitical calculus, the deepening partnership with Russia extends beyond the Ukraine conflict. Russia is a useful partner to gather the Global South in support of building an alternative global order to counter Western dominance. Western sanctions against Russia, and Moscow’s methods of navigating them, provide Beijing with valuable lessons and motivation to develop methods that could shield it from similar measures—particularly in the context of its claim to Taiwan.

The China-Russia alignment has helped Moscow pursue its war against Ukraine and distracted NATO from pursuing any ambitions in the Indo-Pacific. The Trump administration’s pursuit of a peace deal between Moscow and Kyiv could put paid to that and lead the US to reallocate military resources away from Europe to focus on deterring a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan, as Trump’s Pentagon policy lead, Elbridge Colby has argued that the US cannot fight a two fronts war and should focus on deterring China.

The China-Russia alignment is aptly described by the Chinese saying “sharing the same bed with similar, yet different dreams.” Their “no-limits” partnership clearly has limits that are shaped by shifting geopolitical realities shaped by their respective relations with the West, regardless united or not. China signals these limits to reassure the US and Europe that it does not fully support Russia in the war in Ukraine, when the West was pushing Beijing not to support Russian’s war effort. But when seeing Trump talk directly to Putin, Beijing also like to reaffirm the no-limit partnership with Moscow to prevent Moscow from drawing closer to Trump administration. Despite these fluctuations, Xi shares a fundamental common interest with Putin: preserving regime security and working towards an alternative world order.

This analysis is part of the China-Russia Dashboard, a collaborative research effort of the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), MERICS, and the Swedish National China Centre (NKK) and Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS) at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI). Explore the project here.