Made in China’s next chapter: What users on China’s Q&A platform Zhihu are debating

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

Summary

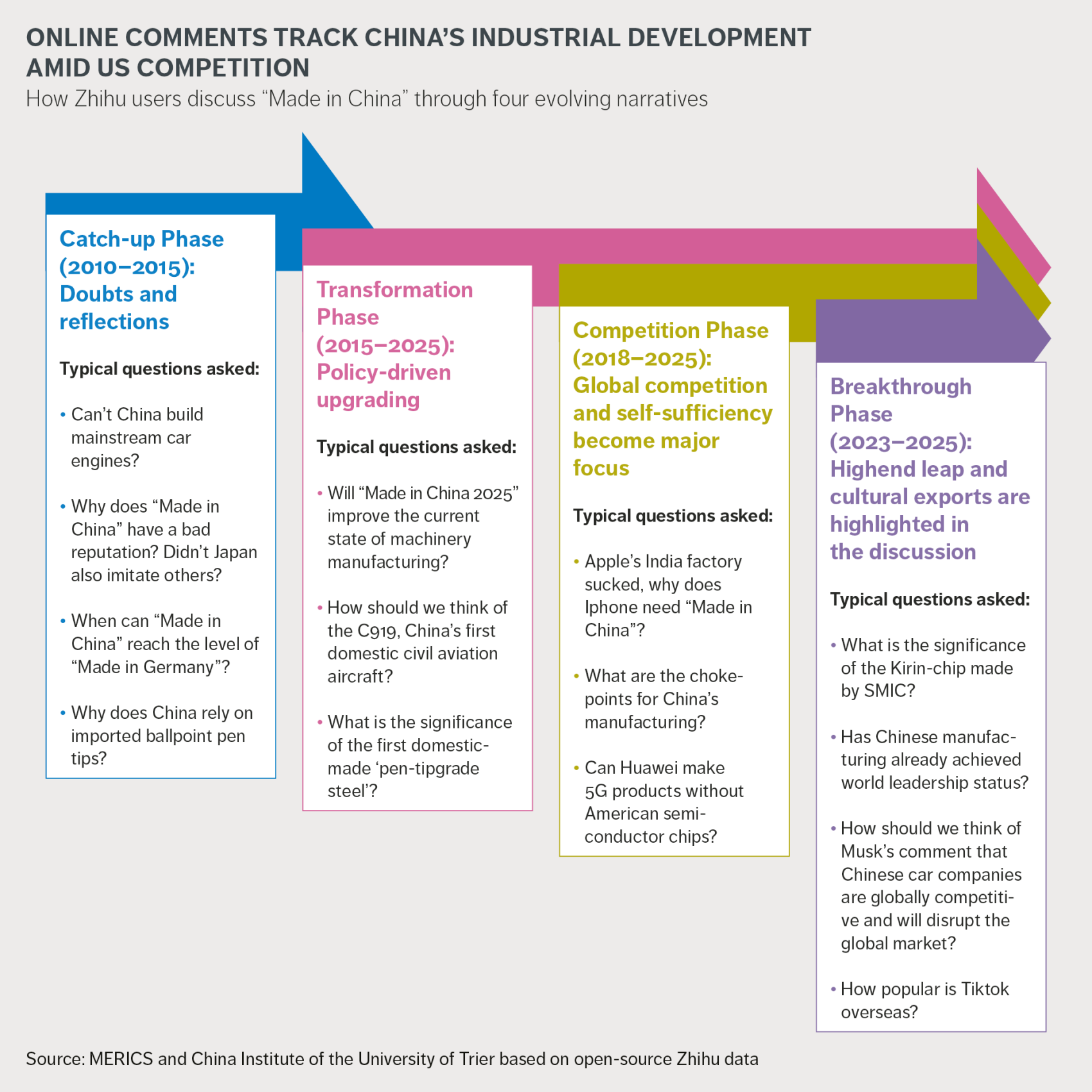

- China’s major industrial strategy “Made in China 2025” was launched in 2015 but soon after disappeared from official discourse. Yet lively online debates on the topic persisted.

- Within the debates, a consensus emerged: different economic sectors require tailored approaches. For example, state-led development works well for capital-intensive industries like high-speed rail or nuclear power, whereas market-driven strategies are more effective in areas such as machine tools.

- Online discussions highlight how poor treatment and widening class divides demotivate workers and raise broader concerns about inequality and social justice in the context of industrial upgrading.

- The question “big but not strong” captures a deeper anxiety in China about whether scale alone can secure global leadership without addressing structural and social weaknesses. While some see China's manufacturing size as its core strength, others warn that without deeper innovation and fairer labor conditions, it risks stagnation beneath its industrial bulk.

According to the “Made in China 2025” strategy, this year was meant to be the milestone year for China’s plan to build one of the world’s most advanced and competitive economies. Launched in 2015, China’s sweeping industrial strategy aimed to upgrade its manufacturing sector by advancing into high-tech fields such as robotics, aerospace, and electric vehicles, while reducing reliance on foreign technology. The plan revealed China's ambition to achieve global leadership in advanced technology sectors traditionally dominated by the West, thereby posing a potential challenge to their economic and technological supremacy.

In response, it caused significant concern of foreign companies, business associations, and governments among major powers such as the United States and the European Union. Over time, these actors came to view China more as a systemic rival than a partner. Since 2018, the term “Made in China 2025” has largely disappeared from official discourse in China, and today no authoritative mention of it is made.

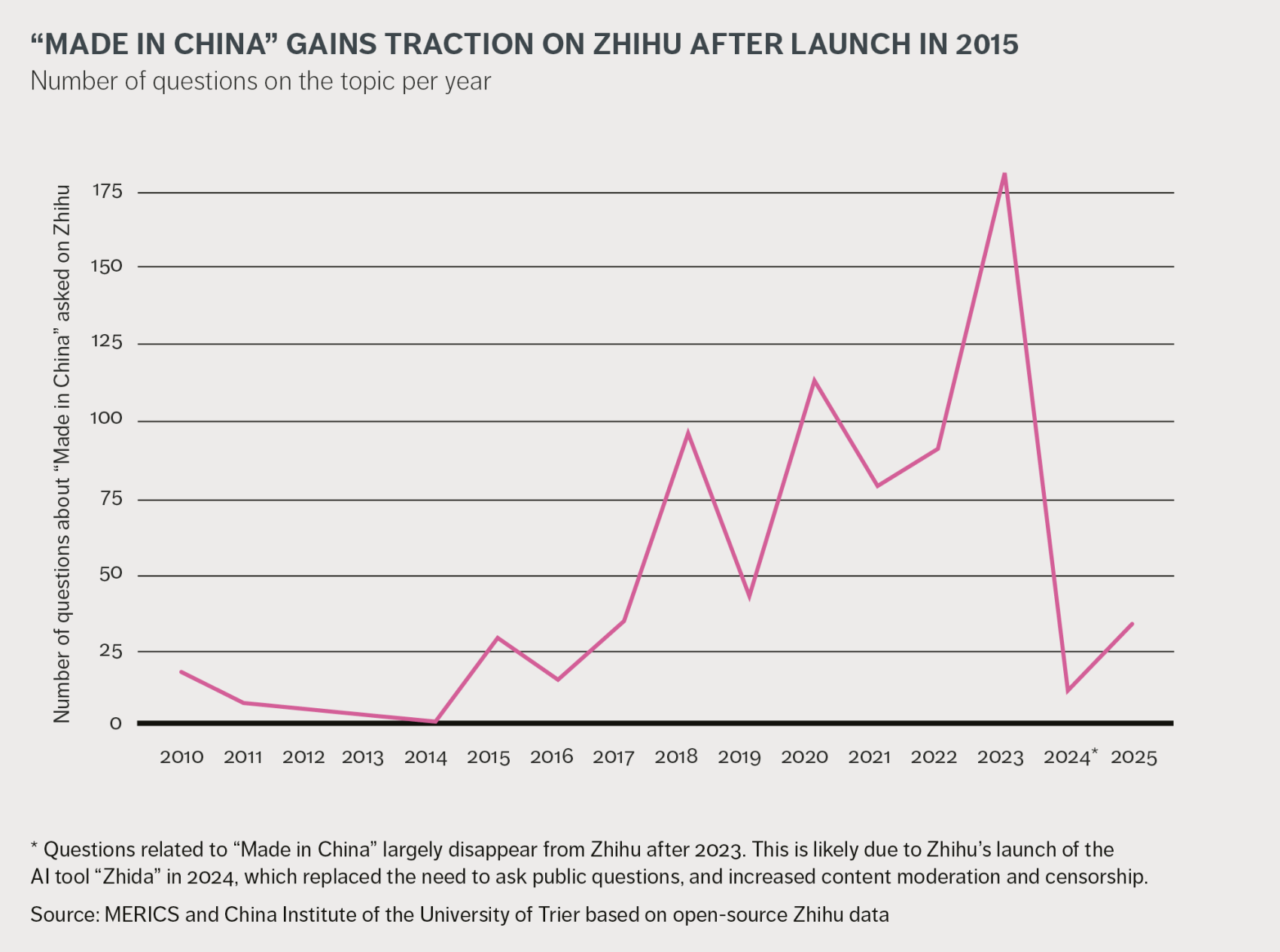

Despite silence at the top, public discussion of China’s industrial ambitions is still very much alive – particularly on Zhihu, a widely used question-and-answer platform that draws in tech-savvy users and industry professionals. Unlike entertainment-oriented platforms like Weibo or more state-aligned sites such as Guanchazhe, Zhihu fosters more in-depth and open exchanges. This makes it a valuable resource for exploring how people in China discuss and assess the development of Chinese manufacturing more broadly.

To tap into those debates, we explored public discussions on the Zhihu topic page titled “中国制造” (Made in China). We focused on a broad range of question-and-answer threads, covering content posted between December 2010 and March 2025.

Our analysis of these discussions paints a nuanced picture: while many users acknowledge significant progress in China’s manufacturing capabilities, they also point to underlying tensions and uncertainties about its long-term direction and implications.

The innovation dilemma: State mobilization or market agility?

One of the most debated topics is whether the market or the state should lead innovation. Advocates for stronger state involvement argue that relying solely on market forces for breakthroughs in core technologies is unrealistic due to steep entry barriers, long development cycles, and the geopolitical necessity of self-reliance. As the user momo [2020]1 insists, “Without policy support, core technologies cannot be developed through market forces alone because newcomers lack both the time and stability to improve products via customer feedback in markets dominated by foreign giants.” Echoing this urgency, Qin Wen [2020] declares: “Even if it takes 10,000 years, we must build our own nuclear submarines,” arguing that unless China develops its own core technologies, “imperialists will not let us live in peace.”

Some commentators, like phymath [2022], argue that the state system (举国体制) is uniquely suited to mobilize the large-scale coordination needed for deep-tech industries like Electronic Design Automation (EDA). EDA involves specialized software tools used in the semiconductor industry to design and create complex microchips and integrated circuits. Success in this field requires decades of interdisciplinary collaboration.

In contrast, critics of strong state involvement emphasize the limitations of centralized planning in fast-moving sectors. Ding Zhaqiao [2022] argues that the success of US tech giants like NVIDIA or Microsoft emerged not from state planning but from a consumer-driven feedback loop. They warn that state-led systems perform well only in long-cycle, low-feedback projects like nuclear energy or aerospace, but fail in IT and semiconductors, where rapid iteration is key – “Moore’s Law moves in 18-month cycles, and you must deliver on time or be swept away.” They also point out the mismatch between rigid planning and community-driven innovation, where new developers in open-source projects can test code and upload features alongside veterans. They argue that China’s top-down system, with its slow feedback loops and rigid planning, can’t match this dynamism.

Gao Tian Liuyun [2022] contends that state-led innovation frequently falls short because “creating a successful product is not the same as building a competitive industry.” He cites the development of the i5 smart CNC system by Shenyang Machine Tools as an example. Despite an investment exceeding 1 billion yuan and securing 10,000 orders, the initiative resulted in a loss of 1.4 billion yuan. Gao states: “While Chinese state research institutions have successfully built world-class equipment, creating a single top-tier machine is very different from establishing a sustainable, globally competitive industry. Unlike sectors like high-speed rail or nuclear power, the machine tool market is highly market-driven. Even with unlimited state support, pilot projects may succeed technically but fail commercially, serving only niche military needs rather than winning in the open market.”

Supporting this view, RainBowThurder [2024] warns that China may be at risk of repeating the Soviet Union’s mistakes: “Administrative power cannot bring about industrial upgrading – it only leads to niche and specialized sectors.” They draw a comparison with the post-Soviet aviation industry, which struggled to thrive despite its technical capabilities.

Together, these voices sketch a divided landscape: one side sees the state as an indispensable anchor for national survival, the other as a bottleneck in the age of agile innovation. The debate is also evident among Chinese experts.

Industrial upgrading at a crossroads: Technological growth first, income distribution later?

As China pushes for industrial upgrading, a key debate is emerging: Is heavy investment in R&D, education, and infrastructure enough – or must better treatment of workers come first?

User Hardpoint [2023] firmly rejects the idea that better labor rights or freer ideology alone can drive progress. In their post “Can Vietnamese manufacturing surpass China’s in three years because they allow strikes and have a more advanced ideology?” they argue that China’s rise rests on “first-class organizational capability” and “decades of technological accumulation, engineering discipline, and infrastructure development.” Fairer labor laws may ease tensions, they admit, but they cannot replace the hard work of building national industrial strength.

Supporting this view, user Information Counterpoint [2023] insists that real wealth for workers will naturally follow industrial advancement. “Low-end sectors must be phased out to free up space, energy, and labor for high-end industries,” they argue. Only after China becomes a global leader in exports of cars, planes, chips, and medical devices, they claim, will workers enjoy “9-to-5 jobs, full social benefits, and family vacations in Europe.”

However, critics warn that this “eating bitterness first, fairness later” approach carries serious risks. RainBowThunder [2024] warns that ignoring income distribution now risks stalling innovation at its roots. “Low wages lead to sloppy work, and sloppy work simply cannot meet the demands of precision industries,” they write. Without raising wages and expanding domestic demand, China will remain dependent on foreign demand for industrial upgrading. They point to Japan’s 1960s income-doubling plan, where rising wages were central to building a tech powerhouse.

Other users highlight a deeper cultural concern. User Find Some Fun [2024] posts a viral photo from SpaceX showing two company chefs proudly featured in a team photo – a stark contrast to the often invisible status of Chinese factory workers. Their point: respect isn’t a luxury; it’s a driver of motivation and innovation.

User Rain on a Sunny Day [2023] adds that even in sectors where China has made great strides, the benefits have not been widely shared. They note a recent joke: “Tesla had to lower wages at its Shanghai factory after competitors accused it of ‘disrupting the market’ by paying workers too much,” implying, ironically, that even arch-capitalist Elon Musk exploits his workers less than some Chinese business owners.

Across these debates, one dividing line becomes clear: whether China’s industrial strength must be built first at all costs, or whether true industrial upgrading depends on sharing the rewards more fairly from the start.

Is Chinese manufacturing “big but not strong”?

China’s manufacturing boom has sparked debate about whether it’s led to industrial upgrading or if it’s simply a scale-based phenomenon lacking high-value output. Some critics argue that China’s model prioritizes quantity over quality, while proponents label them as overly skeptical for not acknowledging China’s rapid development efforts and results.

User Leng Zhe [2023] argues that while China has achieved leading status in a few areas, the overall position is still lacking: “With 1.4 billion people, it’s unacceptable that we have not yet become the global leader in at least three-fifths of industrial sectors.” Similarly, user Fonyuan [2023] points to looming demographic and economic challenges: “Soon, we won’t even be big anymore. Birth rates are collapsing. In the ghost towns at night, you only see a few scattered lights – like ghost fires.” Others, like Yun Zhongjun [2024], tie the industrial problem to broader social issues: “If people aren’t treated with dignity, what’s the point of getting stronger?”

The message from this side is clear: size alone won’t save China. Without boosting worker dignity and deepening domestic innovation, China risks stagnation beneath its massive industrial surface.

But a second camp fires back: China’s scale isn’t a weakness. User MagicJess [2023] ridicules: “Today they call us ‘big but not strong.’ Tomorrow, if we lead in high-tech, they’ll say ‘sophisticated but not strong.’ For some, ‘strong’ simply means ‘not Chinese.’” They back this with hard numbers: In 2023, the United States ran a USD 940 billion trade deficit. Europe and India posted huge gaps too – much of it with China.

User Xiao Huo Man Dun [2023] criticizes endless nitpicking: “Even if one foreign part appears in Chinese technology, they say China’s a fraud. Even if one sector lags, they call it weakness. MagicJess [2023] sums it up: “Big itself is strength. I’ve never seen a strong manufacturing power that wasn’t big. Because strength creates size – and size creates strength.”

Ultimately, while size can be measured in numbers, strength remains a subjective judgment – the debate reflects deeper competing visions of what “strength” really means, and for whom.

The discussions also show how users frame China‘s industrial development in relation to key global players. While Germany for example is seen as the gold standard for manufacturing quality, the US appears as China‘s main geopolitical rival.

Made in China, left behind: The human cost of growth-first policies

Among the topics discussed by Zhihu users, the question of whether China should prioritize income distribution or industrial growth stands out as the most pressing.

Life remains challenging for many rural migrant workers living in China’s cities. The hukou system continues to restrict their access to essential public services such as local schooling, healthcare and affordable housing. Because of this, many are forced to leave their children in their hometowns and live frugally to cope with the high cost of urban life. At the same time, their work is getting less stable. Automation risks taking over many low-skilled jobs, and flexible work models – such as ride-hailing and food delivery – often come with on-demand, short-term tasks with no guarantee of steady employment or ongoing income. Big platform companies also make it difficult for workers to ask for better pay or working conditions, leaving many stuck in low-paid, high-pressure jobs.

At the policy level, the government remains focused on technological progress and industrial upgrading, often at the expense of income redistribution. Leaders have emphasized the need to avoid falling into the so-called “welfare trap,” reinforcing a continued emphasis on supply-side investment and productivity-driven growth.

In this context, the commonly held belief in future fairness as a reward for hard work is increasingly disconnected from reality. A growing sense of disillusionment could be a troubling sign for the broader economy. A workforce that feels undervalued and overburdened can undermine economic resilience – not only through reduced productivity but also by dampening consumer confidence, as pessimistic workers are less likely to spend or invest.

- Endnote

1 | User names are followed by the year of the post in square brackets to indicate when the statement was made.