Is this time different? The structural economic reform challenges for Xi’s 3rd term

This MERICS Primer takes a closer look into the longer-term policy goals set by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the efforts to realize them. The analysis is accompanied by a slidedeck that provides context for and deeper insights on the topic.

In his report at the 20th party congress , Xi Jinping outlined the success of his previous term in office while also building upon his vision for the future of the People’s Republic. Throughout the report were a wide range of development goals that are familiar to followers of China’s policy agenda. While some of the oft-mentioned goals are simpler to make measurable progress on – issues like administrative reform or support for industrial clusters – other, more structural goals that demand considerable change and upsetting of vested interests also reappeared.

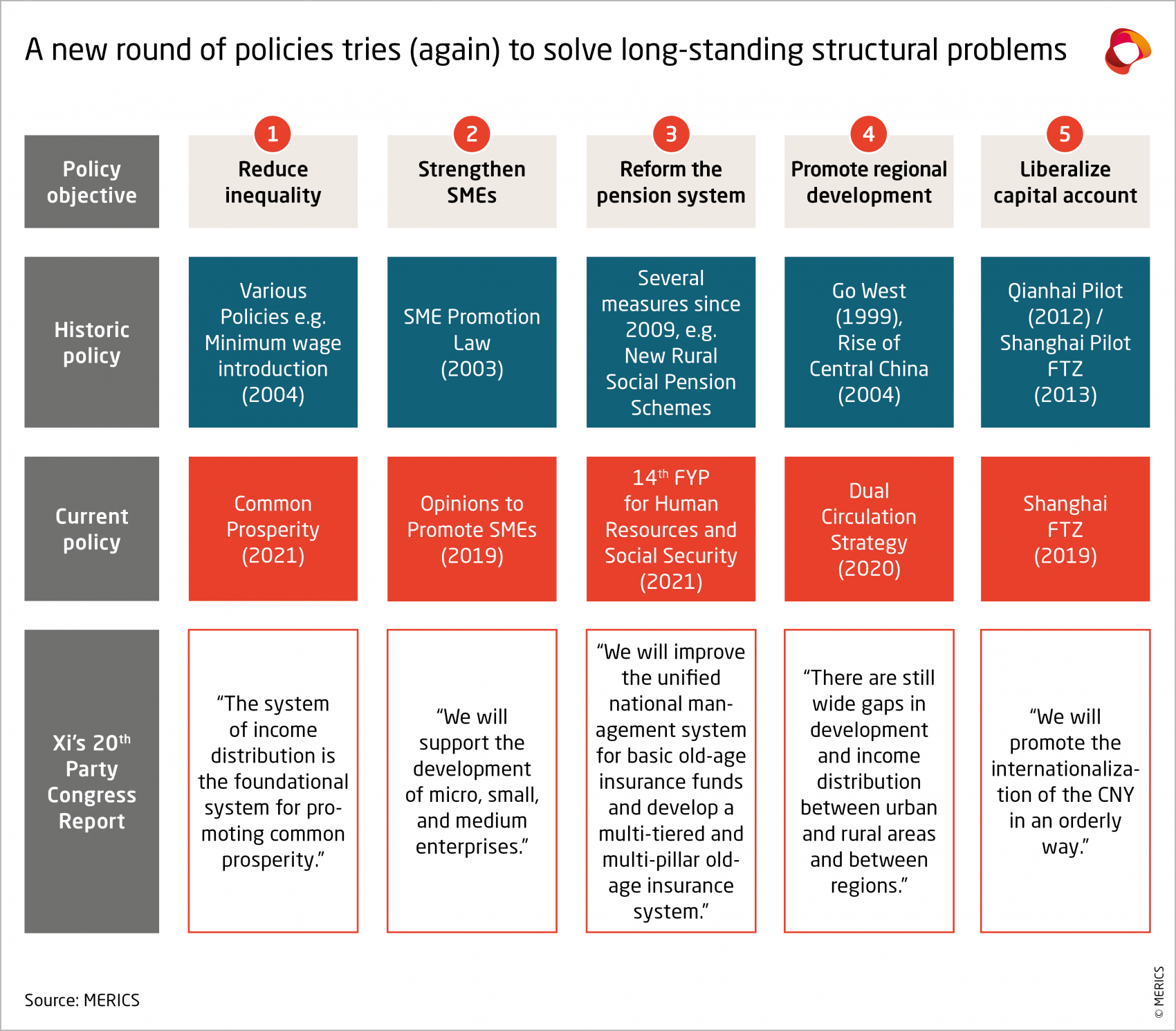

Among that range of issues are five structural reforms to broader development goals that Beijing has repeatedly struggled with advancing. Importantly, these are areas in which the long-term stated policy goals have not meaningfully changed between generations of leadership, unlike, for example, the liberalization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which was advanced by one generation, rejected by the next, then revered under Xi. Instead, these five structural reforms have seen several waves of effort surge forward, only to then be broken up and dissipated by the many inhibitors to structural reform found in the current ecosystem.

Specifically, this MERICS Primer zooms in on the past, present, and future of structural reforms in the following five areas raised, yet again, by Xi Jinping in his 20th party congress report:

- Reduce inequality: “The system of income distribution is the foundational system for promoting common prosperity.”

- Strengthen small and medium-sizes enterprises (SMEs): “We will support the development of micro, small, and medium enterprises.”

- Reform the pension system: “We will improve the unified national management system for basic old-age insurance funds and develop a multi-tiered and multi-pillar old-age insurance system.”

- Promote regional development: “There are still wide gaps in development and income distribution between urban and rural areas and between regions.”

- Liberalize the capital account: “We will promote the internationalization of the CNY in an orderly way.”

Contrary to its self-promoted image, Beijing is struggling to advance meaningful structural reform

Public discourse in Europe frequently compares China’s policy-making apparatus with those of developed liberal market economies as a contest between 3-D chess masters with a 100-year strategy versus amateur checkers players whose planning seldom goes beyond the next election cycle. In public debates in Europe or other high-income democracies, China is often the benchmark against which issues of shoddy infrastructure or slow decision making — in economic policies ranging from digitalization to embracing emerging technologies — are measured. While this account holds elements of truth, a closer look into the longer-term policy goals set by the CCP and the efforts to realize them show more nuanced results.

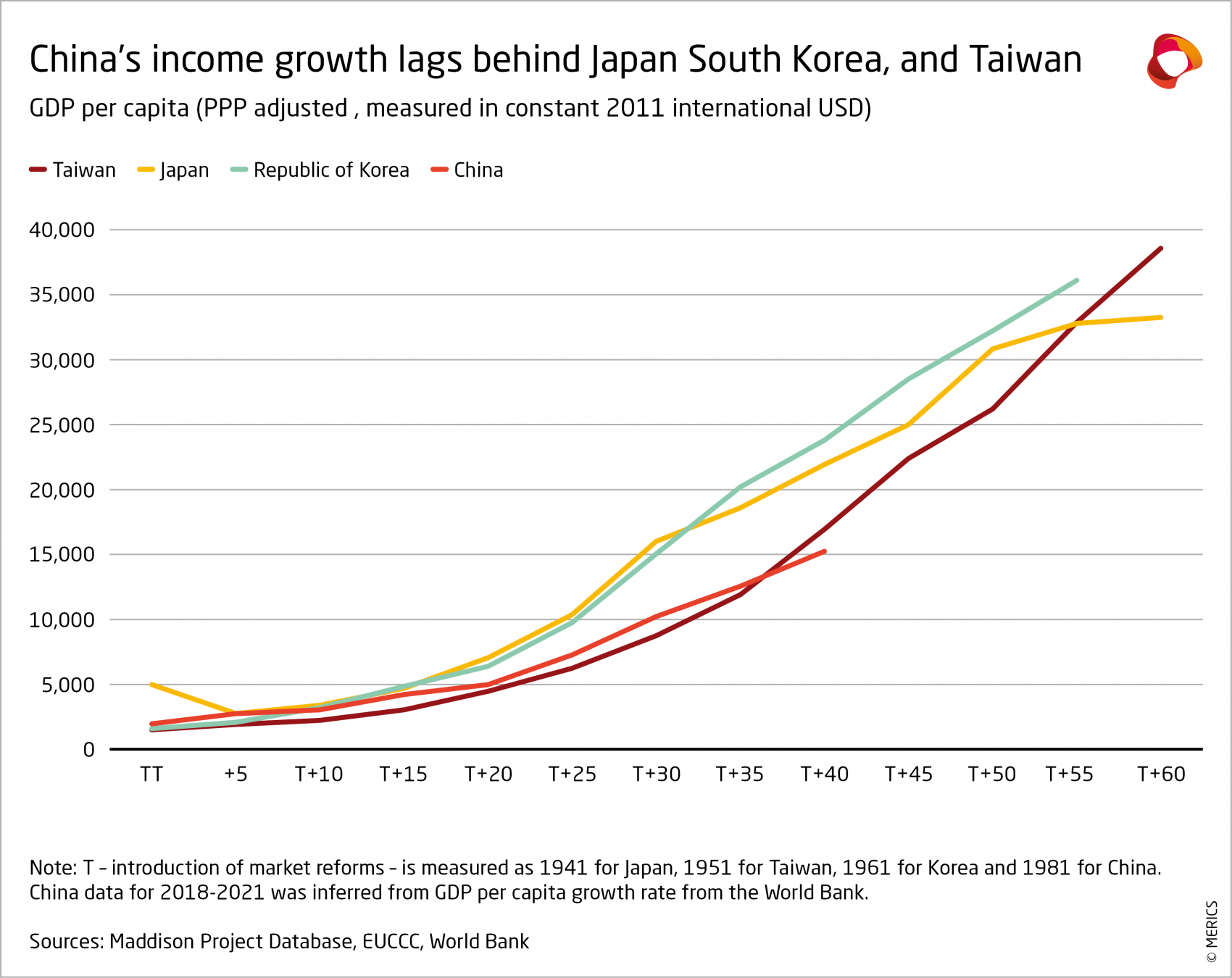

Since the start of the reform and opening-up period in 1978, China has made tremendous strides in its development story. The country’s GDP per capita reached 12,551 USD in 2021 putting it within reach of being classified as a high-income country which the World Bank currently sets at 12,695 USD. In the initial stages of development, picking the ‘low-hanging fruit’ was the means to achieve growth at all costs. However, growth continues to slow, and China may be losing the momentum it needs to keep pace with the development trajectories achieved by its neighbors in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Shifting from an emphasis on such a model towards the much more challenging work of institution building, wealth distribution, and the advancement of the Chinese Yuan (CNY) as a truly global currency will prove deeply challenging for policymakers. Yet, they have spent much of the last several decades trying to resolve certain structural problems with limited results, if any at all. From regional development disparities and income inequality to pension reform, small and medium sized enterprises (SME) development, and capital account liberalization, the party state has struggled to deliver lasting solutions. Instead, macro policies that are rolled out to solve such challenges are often rebranded, dropped or paused after (mostly) lackluster outcomes (see accompanying slide deck for examples).

These efforts stand in stark contrast to the areas in which policymakers have found more success. Beijing has developed a knack for rapid progress in select areas through an ‘industrial policy’ style approach in which considerable capital and manpower are directed to specific issues, leading to timely progress. The success of China’s industrial policy in developing world-leading industries in the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) or photovoltaic cells sectors through such measures has been replicated for resolving social issues under Xi, such as in his signature poverty alleviation campaign that declared itself a success in 2021.

Whether or not President Xi can achieve the kind of progress on key structural issues in the coming years will depend heavily on how his approach compares to previous efforts that stalled. Not only has the General Party Secretary inherited many of these problems, but their growing complexity in a rapidly changing external environment makes them only harder and harder to solve moving forward. Nevertheless, after concentrating power in his own hands for the past decade, Xi has attempted to tackle some long-standing issues in the ‘crackdown on everything’ of 2020 and 2021, which started with Ant Financial, then moved on to the internet platform economy, real estate, and private tutoring.

It may well be the case that ‘this time it’s different’ as the most powerful paramount leader in decades may be able to summon the political will to cut through vested interests and accept the economic price of reform. In order to analyze such prospects, it is critical to understand previous efforts at unravelling the various Gordian Knots in China’s social and economic landscape and to get to grips with the drivers of previous successes, as well as the inhibitors that held back meaningful reform.

Many structural reforms on China’s economic agenda continue to fail from the outset

Advancing key reforms in previous generations took extraordinary resolve to break through vested interests, as well as mass mobilization of capital and manpower, as can be seen in the signature flagship reform priorities of some of China’s leaders.

In the 1990s, Premier Zhu Rongji spent much of his energy on stated-owned enterprise (SOE) reform that sowed the seeds of China’s economic miracle by reforming the Mao-era social safety net — the iron rice bowl - unleashing the private sector and giving it space and capital to grow. Similarly, President Xi Jinping has been eagle-eyed on anti-corruption efforts since the beginning of his administration. Despite the fact that it was also a convenient tool to oust political rivals, the stated intent of the campaign has been largely successful, with even the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China reporting considerable progress — 26 percent of surveyed companies listed corruption as a top three issue in 2014, while only 10 percent did in 2021.

However, in many other areas, China’s economic agenda continues to face long-standing resistance and complexity that have hamstrung repeated attempts to achieve key policy goals. Even before Xi Jinping’s rise to power there have been a number of issues on the policymaker radar that Xi has chosen to prioritize. Ranging from social welfare to financial matters these key areas are undergoing a wave of major policy adjustment, but neither the problems nor the goals are new (see exhibit 2 and the corresponding slides for deeper examination into these areas). New measures can be re-emerging from the policy graveyard or be part of an agenda where progress has been made at a snail’s pace, all of which offer a stark contrast to the narrative of universally streamlined and efficient policy implementation.

Drivers of success: Concentration of resources and political will as well as market developments

Direct action by policymakers has yielded progress in several of these broader policy agendas. For example, decisive efforts from the government bore fruit in addressing the most depredating aspects of income inequality with the alleviation of extreme poverty. Sizeable state resources were directed to China’s poorest citizens, and the very structure of the CCP was leveraged to delegate three million cadres directly to households living on less than 4,000 CNY a year to better manage resource allocation and distribution. The result was an undeniable success in addressing absolute poverty.

However, there are limitations to how this could be replicated at the next level of income, as it would demand higher incomes for a much larger pool of citizens. In this sense, much of China’s direct policy approach to solving these issues remains comparable to its application of industrial policy — allocating resources to addressing a targeted and specific shortcoming.

Market developments that have little to do with government measures — and are rather thanks to the government extricating itself, such as in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone that turned a fishing village into one of China’s most important cities — have also contributed to progress in the structural reform agenda. Relative regional disparity remains high between China’s rich coast and its less developed interior. However, in absolute terms, as coastal wages have risen, China’s core provinces have benefitted from a slow shift in lower-end production moving inland, as well as growing investments from Chinese and foreign companies aiming to tap the growing consumer market of China’s interior.

Similarly, financing access to SMEs has benefitted from the burgeoning venture capital and startup culture developed in the market, and from the fintech industry, though it is notable that these very market sectors and tools have been subjected to intense crackdown on fintech and emerging types of fundraising in recent years.

Inhibitors of success: Stability above all, vested interests and policy schizophrenia

Beijing’s perennial emphasis on stability as the base line of its economic policymaking imposes limits on the kind of major reforms that are necessary to achieve progress on bigger picture issues. In some cases, this takes the form of a clear unwillingness to let market forces play out, such as the steadfast refusal to liberalize China’s capital outflows on the grounds of maintaining the stability of the CNY. As such, efforts to advance meaningful internationalization of China’s currency regime without capital account liberalization generates little more than token results.

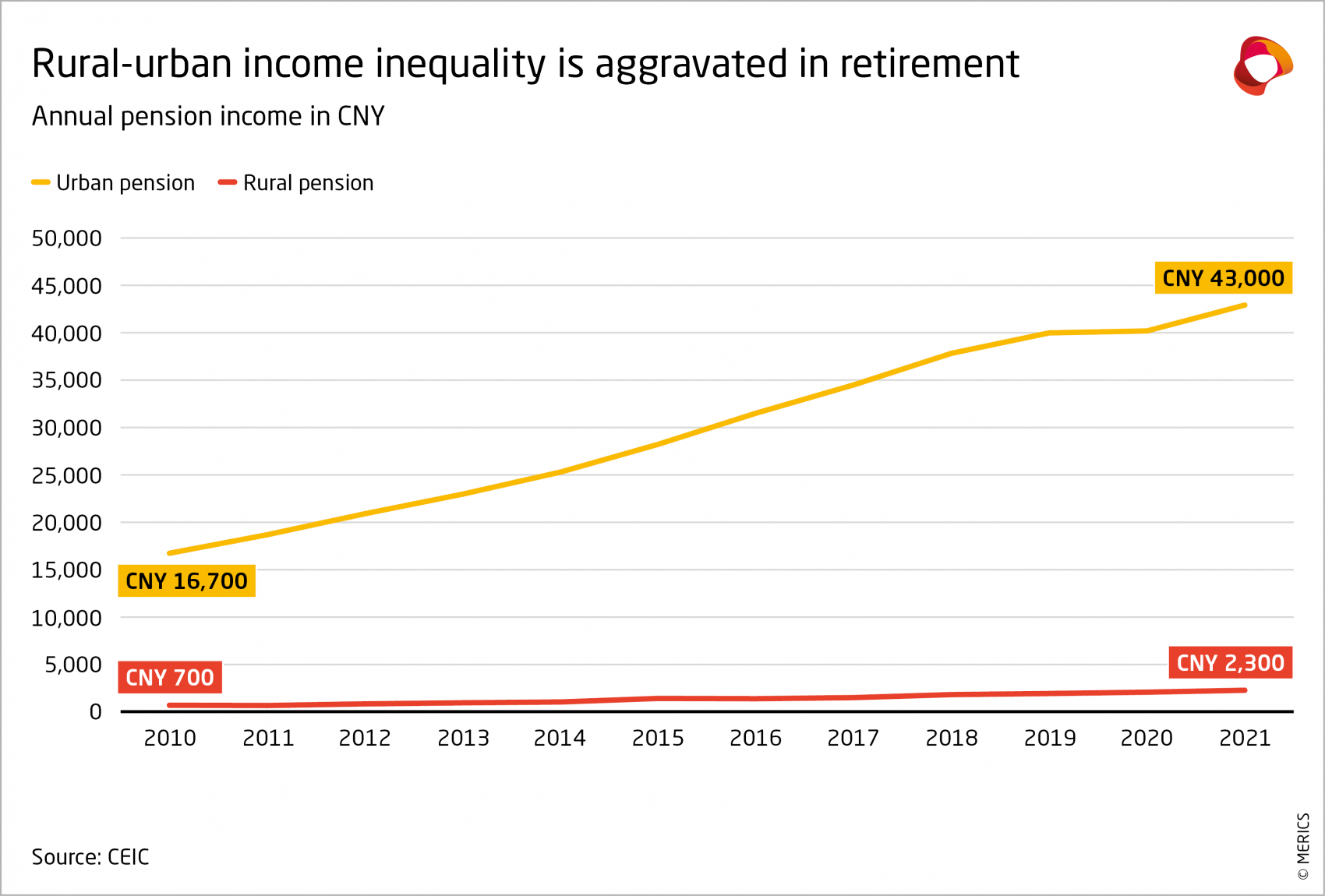

In other areas, prioritizing stability makes it impossible to untangle problems which arise from the intersection of various challenges. For example, income inequality is far higher due to the nature of China’s pension systems and the household registration (hukou) system. These restrict migrant workers’ access to the social security and welfare systems in the cities in which they live and force migrants back to their original locales as they reach retirement age, which also cements regional and individual income disparity. In such cases, one problem cannot be solved without also solving several others at the same time, which could be destabilizing as it risks unwanted side effects, hence the policy gridlock in the name of stability.

The policy agenda is also stagnant in these areas due to political limitations and a wide range of vested interests in the party-state system. The CCP is far from a homogenous block and includes different political factions from liberal reformists to more hardline Marxists. While factionalism is likely at its lowest point in decades under Xi’s consolidation of power, elements of it persist for now and any structural reforms will need to balance between interests of the different factions.

The vested interests of various factions frequently prove to be stumbling blocks. SOEs maintain tremendous amounts of influence over policy, and repeatedly push back on market reforms and changes to financial markets that are necessary to create a stronger foundation for SMEs to thrive in. Similarly, regional disparity alleviation efforts are often hamstrung by the officials and affluent middle class in the country’s developed coastal provinces. This has been seen from resistance to transfer payments to opposition to plans that would require more spots at top universities be reserved for students from poorer provinces.

Another key inhibitor is the mix of policy making and implementation approaches in China. While a strength for achieving quick gains, Beijing’s campaign style approach to policy implementation produces a flurry of activity from officials that dissipates over time. This style, in contrast to institution building, seriously restrains the long-term effort demanded by structural challenges.

One example is in the final months of 2018 when the “battle for blue skies” campaign led zealous officials in Northern China to replace coal heaters with gas ones. This was rushed, and in a demonstration of political zeal, coal heaters were prematurely destroyed even though gas lines and supplies were not yet established. The ensuing winter cold left millions freezing, and once infrastructure was in place, supplies ran short, leading to shortages in industrial centers as far south as the natural gas-rich Sichuan Basin.

Finally, the large host of potential crises facing the CCP at any given moment leads to a kind of policy schizophrenia that inhibits their ability to achieve progress in long-term issues. For example, the 2021 Central Economic Work Conference emphasized stability as the key goal in 2022, but otherwise had a laundry list of every possible economic matter spread over seven broad categories, leaving officials with no clear understanding of where they should put their focus — they know where the problems lie, but do not know which to tackle first. In effect, when officials are expected to achieve progress everywhere, they often end up advancing change nowhere.

The CCP seems to be strengthening its commitment to an authoritarian approach under Xi

With a more powerful Xi Jinping in place the CCP seems to be strengthening its commitment to an authoritarian approach in pushing through policy objectives. The forceful approach will likely be better positioned to break down certain vested interests or political resistance within the party than in the past, perhaps allowing for larger reforms to take shape.

Yet, even when already wielding the power that the core leadership has consolidated over the last decade, a hesitant approach has been adopted towards issues touching on the most widely held of vested interests, such as property owners. Property taxes have been discussed in policymaking circles in the past, but they never went anywhere. Now, Xi’s introduction of property tax pilots as part of the real estate sector shake-up in 2021 are a reminder that despite Xi’s position being strong enough to actually introduce these measures, the cautiousness with which it is being advanced suggests a balancing act not to alienate too many people at once.

The command-and-control approach will leave less room for regional policy experimentation, a hallmark of China’s reform progress in the past. With greater centralization of power and a more ideologically driven political culture, lower-level policy makers will not be willing to stick their necks out and will instead follow what few direct orders they receive, and otherwise do their best to interpret Xi Jinping Thought as gospel for their decision-making.

Corridors of economic activity will become more constrained

This also means that the corridors of economic activity — what private actors can and can’t, or ‘should’ and ‘should not’ do — will become more constrained. There is a shift away from officials adopting pragmatic approaches to solving problems and towards an attitude that favors “engineered” solutions over naturally evolving ones, and even aligning with what is ideologically ‘correct’ rather than what is best from a market perspective. For example, prior to the regulatory crackdown on the fintech sector, China’s private IT companies helped fill a void in China’s state dominated financial system helping to improve among other things access to credit for SMEs. Such solutions would likely be smothered in their infancy by corporate executives that must navigate the complexity of politically appropriate behavior.

Conclusions

China’s political and economic system might very well deliver on some key policy challenges. But this approach is still prone to delivering mixed results. It seems most suitable for breaking vested interests (i.e, SOE reform under Zhu Rongji and regional disparity now) but less so in building underlying institutions (i.e., tackling inequality or strengthening SMEs). Instead, Xi has often relied on ad hoc applications of the CCP as an extralegal force that addresses challenges through short-lived campaigns, which may be suitable for eradicating absolute poverty, but will be insufficient to addressing income disparity in a comprehensive and nationwide way. With a greater emphasis on nationalism and ideology under Xi, there is also an inherent risk of policy makers chasing after propaganda targets at the expense of the long-term structural reform agenda.

However, the success or failure of Xi to meaningfully advance structural reform may be determined less by the drivers and inhibitors of success that affected the efforts of previous generations of leadership and more by challenges unique to Xi’s third term. The 2022 economic downturn stemming from Xi’s prioritization of China’s zero-COVID strategy as well as weak real estate markets resulting from his crackdown on the sector will leave him with fewer resources and less flexibility for bigger reforms – Zhu Rongji had an easier time with SOE reform with a booming, double-digit-growth economy. Furthermore, Xi will almost certainly continue investing resources into China’s technological self-reliance campaign to mitigate the external risk of the US and allies making more dramatic cuts to China’s access to foreign technology. These internal and external challenges may take up all of Xi’s bandwidth, and much of the limited resources that China has to spare as it tries to keep the economy propped up. In that sense, Xi may end up unable to meaningfully advance these structural reforms in the coming years, even if he might otherwise have the right mix of positive factors on his side.