Country Profile: Poland

You are reading the country profile for Poland. Click here to go back to the country profiles overview page.

1. Introduction

Poland’s China policy has moved towards a security and geopolitical focus since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine revealed China’s unwavering alignment with Moscow, and since the case of Chinese economic coercion against neighboring Lithuania. Poland’s earlier enthusiasm about economic opportunities from China has cooled down and it deals with Beijing in a far more skeptical way. The shift has taken place in Poland’s government, but also its people, whose view of China has worsened.

Warsaw has been open in linking Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s threats against Taiwan, and it has strengthened ties with Taipei. Poland’s general election in October 2023 is likely to bring a change in government. However, the major parties seem to have enough political consensus on China to expect the current approach to continue.

2. Key Categories

Economy

In 2022, Poland had the EU’s third largest deficit with China – EUR 34.64 billion - after the Netherlands and Italy. Imports from China totaled EUR 37.5 billion in 2022, or more than 10 percent of Poland’s total imports. The value of its exports to China has been low since 2019, at about EUR 3 billion, or 1 percent of Poland’s exports.

Chinese FDI into Poland is low: only EUR 200 million was invested there between 2020 and 2022, according to Rhodium Group data. Negative views of China have also changed Poland’s stance on foreign investments. It amended its foreign investment screening mechanism in 2020, expanding the list of sectors and entities it covers. China is one of the countries implicitly in focus, though the mechanism is country agnostic.

Warsaw has signaled it wants to reduce the trade deficit and increase economic cooperation with China, but prospects seem rather low amid the worsening of political relations between Beijing and Warsaw.

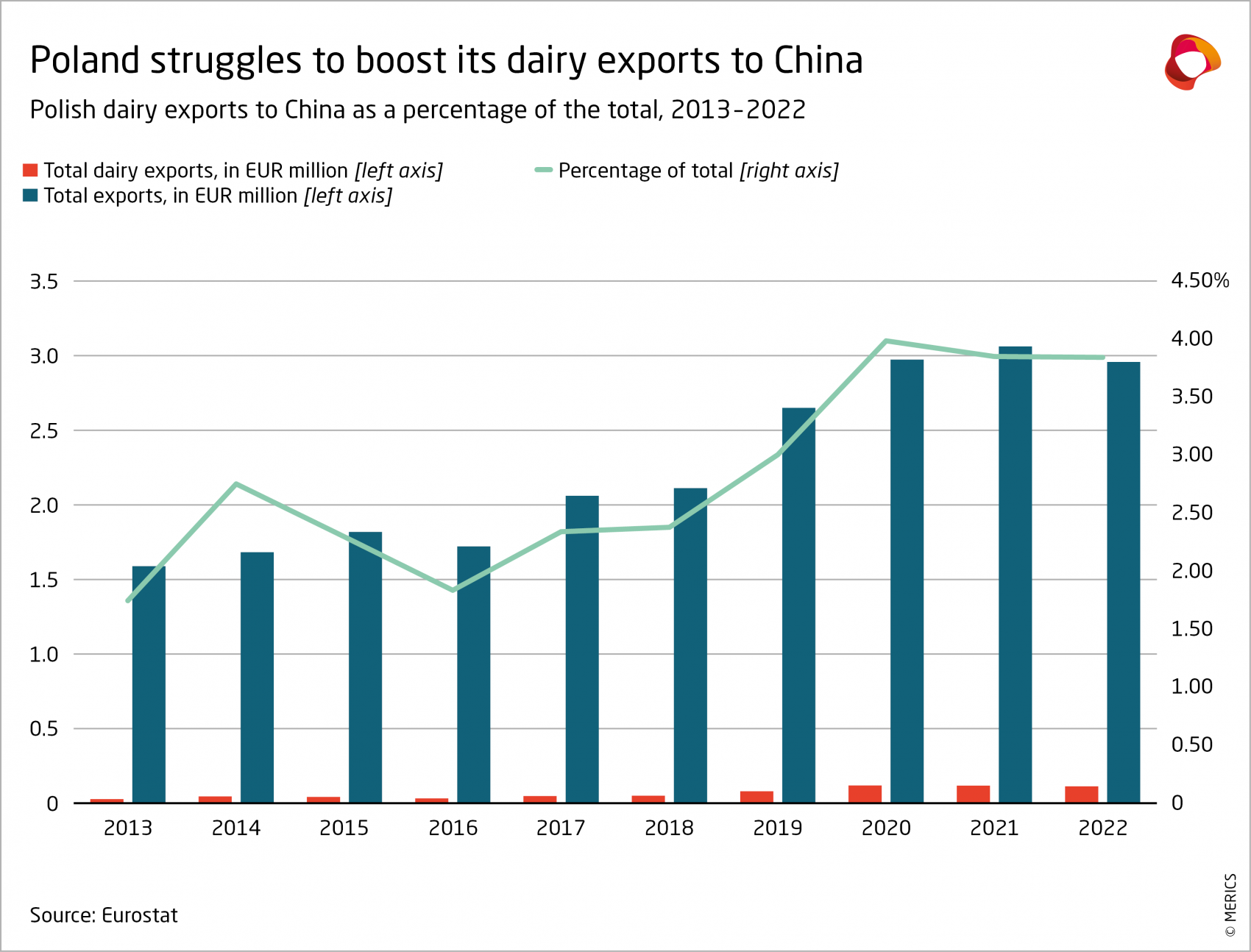

Polish exports to China are dominated by copper products, which were 18 percent of its exports to China in 2022 and around 23 percent in 2021. Warsaw hopes for a boost to its dairy industry exports, given rising dairy consumption and demand in China. But though dairy exports have increased since 2020, they are not yet significant: in 2020, Poland exported dairy products worth a record EUR 118 million to China, which still represented less than 4 percent of its total exports to China.

Politics

The bilateral relationship has deteriorated recently. Initially enthusiastic about the prospects of economic opportunities from China’s market, Poland joined the (then) 16+1 format, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the BRI. Beijing was also seen as offering geopolitical opportunities, and a potential alternative funding source outside of the EU amid complicating relations between Warsaw and Brussels. This approach is all but gone. Disillusioned at the lack of tangible results from endorsing China’s projects, Warsaw’s caution deepened as Beijing gave tacit support to Russia during the invasion of Ukraine. The shift started to become visible before the Covid-19 pandemic but accelerated with Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2022.

High-level political contacts continue between the two sides; the number of engagements stayed fairly stable between 2019 and 2022. Polish President Andrzej Duda was an active interlocutor of Beijing. He participated in the 2021 virtual (then) 17+1 summit despite the lower level of representation sent by most other member countries, and was the only EU leader not to boycott the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022.

Although Poland lacks a formal China strategy, the main political parties seem to be in agreement about the need to develop a more risk-conscious China policy, while avoiding openly antagonizing Beijing. The public debate on China remains limited to specialist circles, although the growing interlinkage with Russia debates has increased China’s prominence in public debates.

China’s economic coercion against Lithuania in 2021 and ensuing Taiwanese outreach towards the CEE region sparked a major shift: Warsaw began strengthening ties with Taipei, albeit in a more low-key way when compared to neighboring Lithuania or Czech Republic. Warsaw’s key objective has been to expand cooperation on high-tech. In 2022, Poland’s deputy minister of economic development and technology Grzegorz Piechowiak visited Taiwan, which led to a MoU to establish a working group on semiconductors. Warsaw has also worked with Taipei to distribute Taiwanese aid, including USD 3.5 million for Ukrainian refugees in Poland and a shipment of 95 tons of winter supplies to Ukraine.

Security

Security concerns about China focus on critical infrastructure and cybersecurity and Beijing’s relationship with Russia. Poland is working on a new cybersecurity law to settle the 5G question. In the meantime, it seems to have banned Huawei, de facto. The Trump administration’s lobbying on 5G led to the 2019 US-Polish declaration to exclude “bad actors” from next generation infrastructure. In January that year, Polish authorities also arrested a sales director at Huawei on espionage charges in a very public case. Poland’s government likely hoped to tighten ties with the United States as relations with Russia worsened – in an implied quid pro quo, Poland stood with Washington on China policy to cement US support in any potential conflict with Russia. Poland has therefore become one of the few EU states to reduce Huawei’s share of its networks, to 38 percent of 5G in 2022, compared to 58 percent of its 4G network in 2022.

Poland has limited security ties or cooperation with China. Between 2019 and 2022, their militaries only met in the context of UN peacekeeping operations. Warsaw has never signed an extradition treaty with either China or Hong Kong. Law enforcement cooperation agreements consist only of agreements on mutual legal assistance in criminal matters, one with the PRC signed in 1987 and one with Hong Kong in 2005.

On dual-use equipment trade, the situation is unclear. Poland used to publish annual reports on arms exports but has not done so since 2019.

Society

In 2023, the Pew survey found 67 percent of Poles had negative views of China. Poland also had the biggest jump in negative perceptions among European countries, up 12 percentage points from 2022 to 2023. By contrast, in 2019 only 34 percent of Pew’s Polish respondents had negative opinions of China. This rapid shift is most likely due to Beijing’s stance on Russia’s war in neighboring Ukraine.

People-to-people exchanges between China and Poland are limited and stable, despite worsening relations. Roughly 9,000 Chinese citizens are registered as living in Poland and about 1,250 Chinese students attend Polish universities. As elsewhere, Chinese tourist visits fell from 137,000 (or 0.4 percent of Poland’s 36.5 million tourists that year) to only 28,000 in 2022. It remains to be seen if numbers will climb again.

Academic exchanges also seem immune to the political and security tensions so far. Poland hosts six Confucius Institutes and the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) has identified 617 agreements between Polish and Chinese universities. Most do not imply heightened risks, but some research collaborations have potential dual-use or military implications, with little debate or apparent awareness of the risks. For example, the Polish Academy of Sciences received 2 million Polish zloty (PLN) – equivalent to almost EUR 430,000 – to research topological materials (with potential applications in making quantum computing memory units) with the Beijing Institute of Technology, one of China’s ‘Seven Sons of National Defense’.1

- Endnotes

-

1 | https://academytracker.ceias.eu/articles/6yquKSFOjr8qAyMnRBKWck

You were reading the country profile for Poland. You can return to the country profiles overview page here.

This MERICS analysis is part of the project “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.