Kazakhstan’s three-way balancing act between competing powers is under pressure

You are reading chapter 4 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 4 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

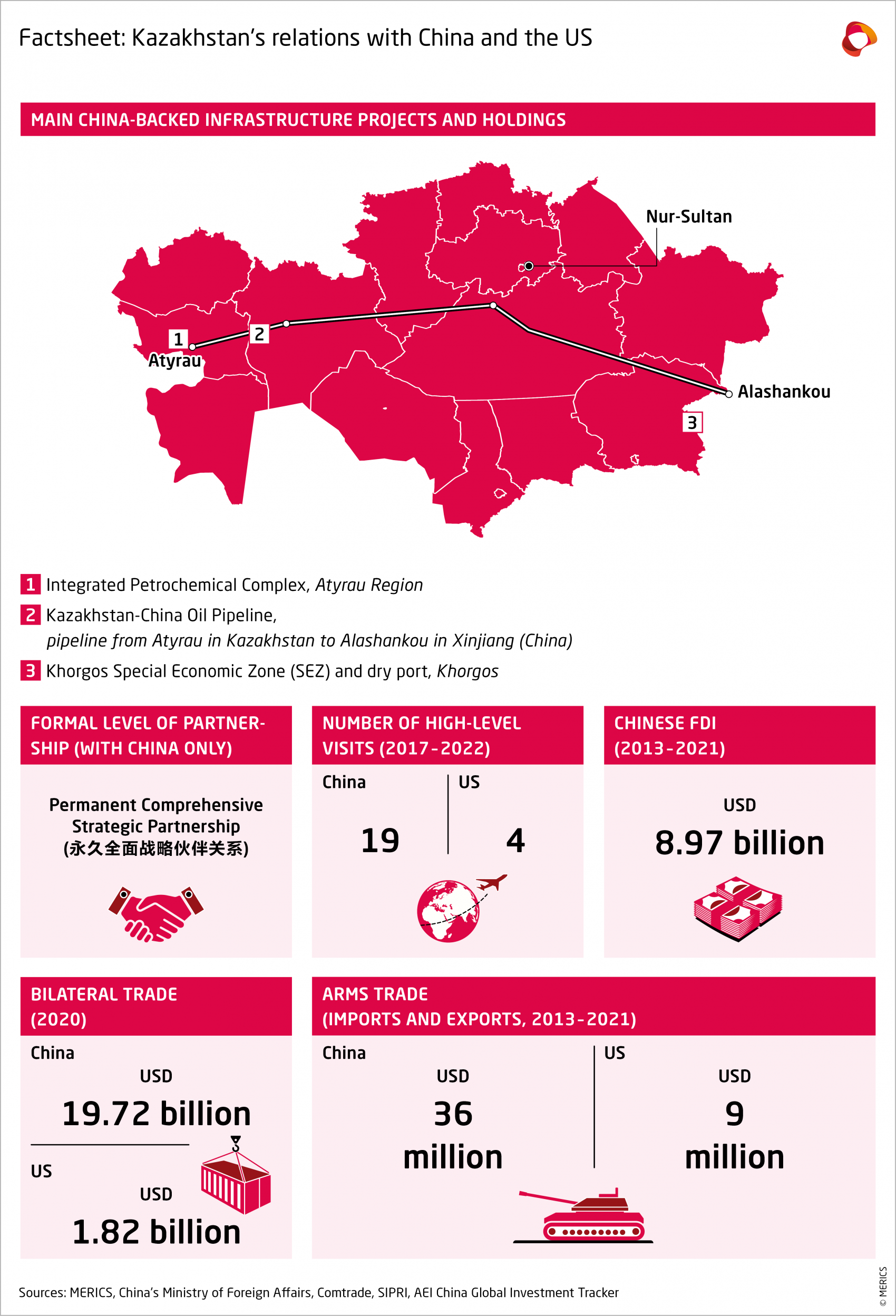

As one of Kazakhstan’s biggest trading partners and investors, China has prioritized the economic relationship over the military one. However, China is becoming more interested in acting as a security provider in Central Asia, given the instability in Afghanistan and growing securitization of Xinjiang. China’s increasing presence in Kazakhstan has provoked concern among expert groups and the wider public, though Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime makes it hard for public opinion to shape policy. Nonetheless, widespread public outcry has sometimes shifted policy towards China. Kazakhstan’s ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy and trade diversification strategy could be undermined by greater economic dependence on China, as Russian’s attack on Ukraine will strengthen China’s role as an economic partner. Kazakhstan needs to diversify its oil and gas-dependent economy, channel more investment into value-added technologies and plan for a low-carbon future. Russia’s unpredictability might also open the way to an alternative security system in Central Asia. Rising tensions between Russia, China and the West could mean Kazakhstan’s three-way independent policy gets squeezed by pressures to take sides.

Status quo: Oil and gas-dependent Kazakhstan needs Russia, China and the West

Kazakhstan’s relationship with China is driven by trade and investment. In 2021, China was the largest buyer of Kazakhstan’s exports (taking 16.4 percent) and second only to Russia as a source of imports, providing 20.2 percent of the total. Kazakhstan predominantly exports commodities – oil and gas, coal, uranium, zinc and iron ores, agricultural and chemical products – and imports industrial goods such as food, light manufacturing goods, medicine, electronics and machinery from China. Total trade between the two amounted to USD 18.19 billion (17.9 percent of the total) and rose 15.2 percent in 2021 compared to the previous year reflecting the ease of Covid-19 trade restrictions.1

China is Kazakhstan’s fourth largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI), after the Netherlands, the United States, and Switzerland. Total gross inflow of FDI from China, excluding Hong Kong, was USD 18.9 billion between 2005 and 2019, roughly 6 percent of total investment in the time.2 The bulk of Chinese FDI goes into joint ventures in extraction, especially oil and gas and other minerals. Other destinations include manufacturing, communications, and service industries.

Kazakhstan’s debt to China was 5.9 percent of its total external debt in April 2021, or USD 9.7 billion, which included government-guaranteed debt of USD 1.39 billion, according to official data.3 Kazakhstan ranks as China’s fifth-largest recipient of grants and loans, having received USD 39.01 billion from official Chinese institutions from 2000 to 2017. It is among the 10 countries whose hidden debt to China (or loans issued to state-owned enterprises with implicit host government repayment guarantees) amounts to more than 10 percent of GDP.4

In the security sphere, Kazakhstan is one of the original members of the Shanghai Five grouping (which became the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, or SCO), set up in 1996 in the aftermath of the disintegration of the Soviet Union to settle territorial disputes between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and China. The SCO countries have held joint military training, fostered academic exchanges and cooperated against the three evils of “terrorism, separatism and extremism.” China is particularly concerned about those three threats in relation to Afghanistan and its own Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. China’s only military base in Central Asia is in Tajikistan, which borders both Afghanistan and China.

Kazakhstan’s government has a vested interest in Afghanistan’s stability, given its proximity and the potential for radical groups to influence Kazakhstan’s own, predominantly Muslim population. The Kazakh public takes a close interest in China’s persecution of the Muslim Uyghurs and Kazakhs in Xinjiang. Hence, the Kazakh government must juggle between keeping close relations with China and responding to popular demand for action to protect Xinjiang’s Kazakh minority. The government has cracked down on activists and protesters seeking information about missing relatives in Xinjiang, but also sent diplomatic notes of protest to Beijing.5

China’s military did not get involved in pacifying protests in Kazakhstan in early 2022, despite Beijing’s concern for stability in Central Asia. Military involvement was coordinated under the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), not the China-led SCO. Beijing embraced the official Kazakh narrative that the protests were a color revolution instigated by external forces and promised its support to overcome the difficulties.6

Geopolitics: Kazakhstan cherishes its “multi-vector” foreign policy doctrine

Kazakhstan has followed a multi-vector foreign policy since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, triangulating between Russia, China and the United States. After the January 2022 protests, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said Kazakhstan would remain open to multifaceted cooperation with the international community.7

On the economic front, Kazakhstan is finding it harder to maintain its foreign policy balancing act between Chinese or Russian influences to fend off US pressures. Chevron and other US companies remain leading oil producers in Kazakhstan, accounting for 30 percent of total oil extracted in 2019. This compares with 17 percent pumped by China’s CNPC, Sinopec, and CITIC, and 3 percent for Russia’s Lukoil.8 The US has attempted to engage with Kazakh financial sector initiatives via a USD 1 billion project from its International Development Finance Corporation to implement joint investment projects through the Astana International Financial Center platform,9 and through Washington’s response to China’s BRI – the Blue Dot Network.10 Although these are meaningful initiatives, US-Kazakhstan trade turnover of USD 2.3 billion in 2020 is tiny compared to USD 18.19 billion of trade with China. Nor can the relationships be seen as comparable, given the scale of Chinese investment, financing, and infrastructure support.

Kazakhstan’s triangulation strategy can clearly be seen in military co-operation. Russia is its primary military partner11 but Kazakhstan has hosted the annual ‘Steppe Eagle’ military exercise with NATO since 2006. It was last held in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.12 From 1991-2020, the US and China each supplied a minor and roughly equal share of Kazakhstan’s total arms imports; 1.3 percent from the US, against 1.1. percent from China.13 The informal and low-grade nature of the US-Kazakhstan security relationship allows Kazakhstan to maintain its multi-vector foreign policy and not upset Russia.14 China’s role has been mainly economic, though Afghanistan’s instability has increased China’s interest in adopting a regional security role.

For the United States, as for China, the two most prominent security issues in the bilateral relationship are Afghanistan and Xinjiang. Both the United States and China are concerned that radical Islamic terrorism in Afghanistan could become a source of regional instability. After the US withdrew its troops in 2021, Afghanistan’s political settlement and stabilization became an interest for China and Russia, just as much as for Central Asian states, and Washington. Xinjiang, on the other hand, is a source of US-China tension and political confrontation. During his official visit to Kazakhstan in February 2020, then US Secretary of State Pompeo urged Kazakhstan to join in pressing China to end its repression of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang.15 However, he failed to persuade Kazakh officials to take a harder line that would have disrupted Kazakhstan’s balancing act.

Perceptions: China is more popular with elites than with the public

The axiom “warm politics, cold public” could have been coined to describe the Sino-Kazakh relationship. The political establishment and the business elites exhibit a cautious pro-China approach, while the wider public is divided. Public opinion readily equates China with Chinese migrants who are often perceived in a negative light.16 Despite the growing number of anti-China protests,17 the Kazakh and Chinese governments enjoy stable high-level relations, underpinned by a 2019 bilateral agreement on a permanent comprehensive strategic partnership. Kazakhstan’s authoritarian nature makes it hard for public concerns to directly impact policy making, though widespread public outcry has sometimes produced policy shifts, as happened with the suspension of land reforms in 2016.

Both expert groups and the public have expressed concern about China’s increasing presence in Kazakhstan. The expert survey “Central Asia Forecasting 2021” found that China’s regional role was expected to grow, leading Beijing to challenge Moscow’s position as the preferred partner of all five states. This was not necessarily a welcome trend; fears included the likely adoption of China-style surveillance technologies and other authoritarian practices.18 Popular views recorded by the Central Asian Barometer also revealed concern; only 7 percent of Kazakh respondents “strongly supported” Chinese energy and infrastructure projects and more than 70 percent were very concerned at the prospect of Chinese land purchases.19

Anti-China protests spread across several cities in 2019 on the eve of President Tokayev’s first official visit to China. Demonstrators protested against the rumored relocation of 55 Chinese factories20 to Kazakhstan. They cited fears about pollution, and rising debt, while also objecting to the mistreatment of Uyghurs and Kazakhs in Xinjiang.21 A preliminary list of the factory projects had been drafted in 2016, but was only publicly disclosed in 2019 after the protests.22

Transboundary water management and land ownership issues also worry the Kazakh population. Two key rivers, the Ili and Irtysh, remain contested, with negotiations on water management and use underway since 1999. Additionally, the growing Chinese presence has seen widespread fears of land takeovers gaining momentum over the past decade. In April-May 2016, people in several cities successfully protested draft amendments to the Land Law that would have permitted foreigners to rent agricultural land for 25 years instead of 10 years. Concerns focused on Chinese citizens, many of whom already work on rented agricultural lands in Central Asia.23 The land reforms were eventually suspended.

The Kazakh public has few ways to influence official policy: Kazakhstan is classed as a consolidated authoritarian regime by Freedom House.24 However, the land protests of 2016 and anti-China protests of 2019 succeeded: land reform was suspended and the “55 projects” list became publicly available. Public opinion cannot be completely disregarded in Kazakhstan’s relations with China.

Outlook: Economic diversification is more urgent than ever

President Tokayev promised Kazakhstan’s major policy paradigms would remain unchanged when he won the June 2019 presidential election, ending the 30-year presidency of Nursultan Nazarbayev. He has continued to follow the ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy that balances pressures from Russia, China and the United States, along with “controlled democratization” and social reforms.25 However, President Tokayev may have over-indebted himself to Russia in January 2022 – and unbalanced Nazarbayev’s carefully-calibrated independent foreign policy – when he asked the Russian-led CSTO to help suppress violent riots in Almaty, the biggest city and commercial metropolis.26

For now, however, Russia’s war in Ukraine has swung Kazakhstan away from Russia and towards China. International sanctions against Russia have worsened Kazakhstan’s economic woes, coming so soon after the January 2022 protests hurt the investment climate. As Kazakhstan seeks to diversify away from Russia, it is likely that China will play a bigger role, given its proximity, sizeable market and alternative financial institutions. Other factors pushing Kazakhstan towards China are the fear of sanctions affecting Kazakh oil in Russian pipelines and risk of secondary sanctions. Yet, China’s Covid-19 management strategy of continuous lockdowns has slowed trade and business travel this year. More broadly, the government will need to weigh whether greater economic dependence on China’s jeopardizes its balanced foreign policy.

The top economic policy in need of revision under current circumstances is the trade diversification strategy and structural transformation of the energy sector. Kazakhstan gets almost 45 percent of its government budget from oil and gas revenues27 – it was the world’s ninth-largest exporter of crude oil and 12th for natural gas in 2018, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) data.28 Shifting patterns of global energy consumption mean Kazakhstan needs to channel more investment into oil and gas processing and value-added technologies to diversify its products; yet it must simultaneously plan for a low-carbon future and develop alternative energy sources.

In security policy, Russia’s unpredictability, and the rise of anti-colonial sentiments in Central Asia, could lead to a push for an alternative Central Asian security system. The Kazakh government’s heightened sensitivity to public opinion after the January protests could also play into this. Here, Kazakhstan’s multilateralism could form the basis of a new regional system, with countries drifting away from Russia to engage more with China, Turkey, the West, and the Arab world. However, rising tensions between China and the West may also hinder Kazakhstan’s ability to continue to maneuver between opposing interests.

- Endnotes

-

1 | State Revenue Committee (2021). Statistics of foreign trade of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://kgd.gov.kz/en/exp_trade_files. Accessed: February 24, 2022.

2 | National Bank of Kazakhstan (2021a). Direct Investments according to the directional principle. https://nationalbank.kz/en/news/pryamye-investicii-po-napravleniyu-vlozheniya. Accessed: November 12, 2021.

3 | National Bank of Kazakhstan (2021b). External Debt. https://nationalbank.kz/en/news/vneshniy-dolg. Accessed: November 12, 2021.

4 | Malik AA, Parks B, Russell B, et al. (2021). Banking on the Belt and Road. Insights from a new global dataset of 13427 Chinese development projects. https://docs.aiddata.org/ad4/pdfs/Banking_on_the_Belt_and_Road Insights_from_a_new_global_dataset_of_13427_Chinese_development_projects.pdf. Accessed: December 11, 2021.

5 | Pron E and Szwajnoch E (2019). Kazakh Anti-Chinese Protests and the Issue of Xinjiang Detention Camps. https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13593-kazakh-anti-chinese-protests-and-the-issue-of-xinjiang-detention-camps.html. Accessed: April 25, 2022.

6 | Xinhua News Agency (2022). Xi sends verbal message to Kazakh president. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/20220107/1d680adbf493472488e555e2ed523bfc/c.html. Accessed: March 31, 2022.

7 | Akhmetkali A (2022) “Open Door Investment Policy Remains Consistent, Says Kazakh President,” The Astana Times, 27 January.

8 | Umarov T. Carnegie Moscow (2021). “Can Russia and China Edge the United States Out of Kazakhstan?”8 March. https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/85078. Accessed: April 2, 2022.

9 | Prime Minister of Kazakhstan (2021). Kazakhstan is developing investment cooperation with the United States through AIFC platform. https://primeminister.kz/en/news/kazahstan-narashchivaet-investicionnoe-sotrudnichestvo-s-ssha-cherez-ploshchadku-mfca-805939. Accessed: April 2, 2022.

10 | Cekuta R (2020). “Blue Dot Network: Avenue for Increasing Investment.” The Astana Times, 28 September.

11 | Neafie J (2022). “Producing the Eurasian Land Bridge: a case study of the geo-economic contestation in Kazakhstan.” International Politics: 1–21.

12 | Putz C. The Diplomat (2022). “Russian Ambassador to Kazakhstan Says US-NATO Steppe Eagle Exercise Will ‘No Longer Fly’.” 11 February. https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/russian-ambassador-to-kazakhstan-says-us-nato-steppe-eagle-exercise-will-no-longer-fly/. Accessed: April 4, 2022.

13 | Zholdas A (2021). Import of Arms in Central Asia: trends and directions for diversification. https://cabar.asia/en/import-of-arms-in-central-asia-trends-and-directions-for-diversification. Accessed: April 4, 2022.

14 | Neafie J (2022). “Producing the Eurasian Land Bridge: a case study of the geo-economic contestation in Kazakhstan.” International Politics: 1–21.

15 | RFE/RL (2020). “Pompeo Urges Kazakhstan to Press China Over Xinjiang Crackdown.” Voice of America, 2 February.

16 | Chen Y-W (2015). “A Research Note on Central Asian Perspectives on the Rise of China: The Example of Kazakhstan.” Issues & Studies 51(3): 63–87.

17 | Toktomushev K (2021). “China and Central Asia: Warm Politics, Cold Public.” CAP PAPERS 261.

18 | Baldakova O, Schiek S, Rinke T, et al. (2021). Central Asia Forecasting 2021: Results from an Expert Survey. https://centralasia-forecasting.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ca_forecasting_report_web_en.pdf. Accessed: July 4, 2022.

19 | Trilling D (2020). “Poll shows Uzbeks, like neighbors, growing leery of Chinese investments.” Eurasianet, 22 October.

20 | The idea of such Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation was first announced in 2014 under the framework of linking Kazakhstan’s own infrastructure development strategy, Nurly Zhol, to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

21 | Baldakova O. MERICS (2019). “Protests along the BRI: China’s prestige project meets growing resistance.” December 10. https://merics.org/en/analysis/protests-along-bri-chinas-prestige-project-meets-growing-resistance. Accessed: April 11, 2022.

22 | Yergaliyeva A (2019). “Kazakh President, officials deny rumours China will transfer 55 old factories to Kazakhstan.” The Astana Times, 7 September.

23 | Pannier B (2016). “Central Asian Land and China.” Radio Free Europe, 2 May.

24 | Freedom House (2022). Kazakhstan: Country Profile. https://freedomhouse.org/country/kazakhstan. Accessed: April 12, 2022.

25 | Gotev G. EURACTIV (2019). “Kazakhstan’s new president vows to pursue controlled democratisation.” September 3. https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-asia/news/kazakhstans-new-president-vows-to-pursue-controlled-democratisation/. Accessed: April 13, 2022.

26 | Stronski P. Carnegie Moscow (2022). “Lessons Learned from the Kazakhstan Crisis.” 16 February. https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/86450. Accessed: April 13, 2022.

27 | Forbes (2020). “44% of the state budget of Kazakhstan is formed by the oil and gas sector.” February 4. https://forbes.kz/process/energetics/44_gosudarstvennogo_byudjeta_kazahstana_formiruet_neftegazovyiy_sektor/? Accessed: November 23, 2021.

28 | IEA (2020). Kazakhstan energy profile. https://www.iea.org/reports/kazakhstan-energy-profile. Accessed: April 16, 2022.

29 | Lillis J (2022). “Ukraine war inspires rival passions in Central Asia.” Eurasianet, 7 March.

30 | Petrenko R (2022). “Kazakhstan does not recognise the “republics” in ORDLO and rules out sending CSTO troops there.” Ukrayinska Pravda, 22 February.

31 | Kumenov A (2022). “Kazakhstan braces for impact of Russia sanctions regime.” Eurasianet, 3 March.

You were reading chapter 4 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You were reading chapter 4 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.