China keeps generative AI on simmer

Beijing's attitude towards generative AI seems to be one of measured progress rather than cutting-edge innovation, says Wendy Chang. AI technologies should serve its goals of modernizing the manufacturing base and developing high-tech, higher value-add industries.

Since the arrival of ChatGPT, companies everywhere have been racing to build on the early success of large generative AI models that can produce texts and images, answer prompts, and perform other sophisticated tasks. But China’s adoption of the transformative technology has been lukewarm, even though Beijing sees artificial intelligence as a key driver of economic and military competitiveness.

Given generative AI’s potential to upend China’s meticulously censored domestic internet, this comes as no surprise. It reflects President Xi Jinping’s heightened focus on perceived threats to national security. China’s generative AI therefore faces significant challenges to innovate and compete with Western rivals. Beijing’s support for AI lies instead in applications it hopes will revitalize its industrial sectors, creating competition for Western firms with leadership positions in industrial AI.

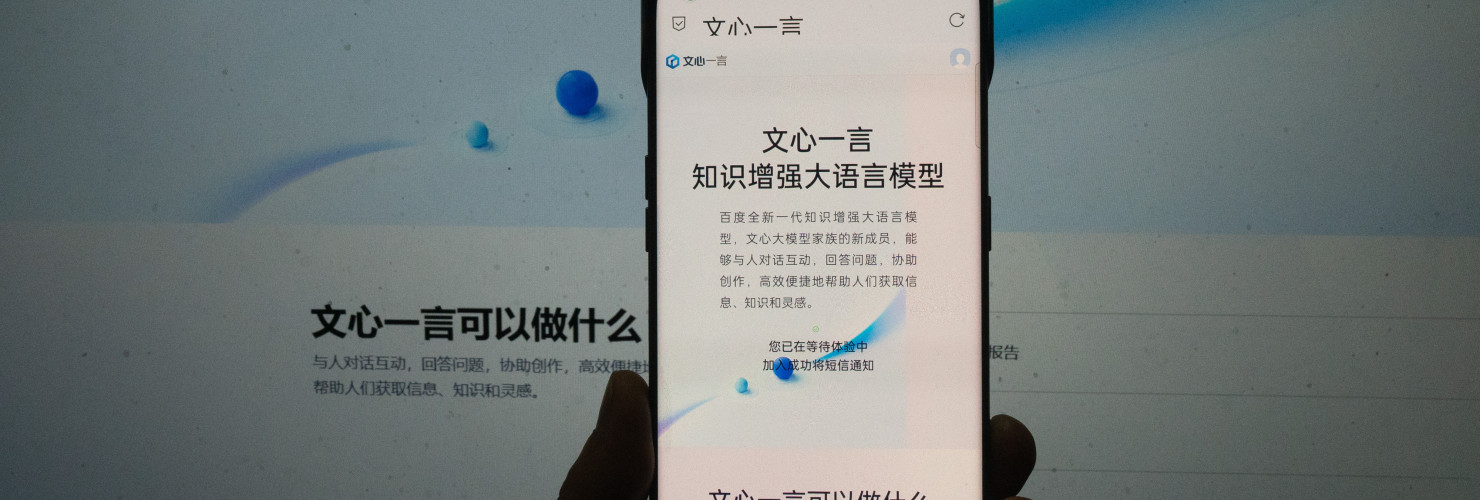

Generative AI is sparking a frenzy of developments that will vastly alter how we use technology. On the heels of ChatGPT, Google and Meta each released chatbots backed by their own Large Language Models (LLMs). In comparison, China’s large tech companies were curiously muted – their first serious contender, Baidu’s ERNIE Bot, was announced but not released for months. From the get-go, the Chinese government was strict with chatbot technology – ChatGPT was inaccessible and approval of domestic offerings withheld. It wasn’t until August 2023, a full nine months after ChatGPT’s release, that Beijing finally allowed public access to the first generative AI services. This attitude has directly affected the vibrancy of its tech community’s development of generative AI.

Headwinds from inside and outside China

Beijing has been working with remarkable speed on AI regulation, alert to the potential threat of AI-generated content for its heavily censored internet. Its 2023 regulation on generative AI services requires large models to be registered with the state’s algorithm registry, to meet truth and accuracy requirements, and to “reflect Socialist core values.”

The cyberspace administration has since released its own set of approved LLM training data. Influential technical working group TC260 provided additional, stringent and remarkably detailed standards on input training data and the output of a model. Notably, development based on unregistered foundational models is explicitly forbidden, so foreign open-source models cannot be used. While large tech companies often actively help shape these standards, compliance could still be very costly for them. Smaller companies or entrepreneurs could well be discouraged from venturing into this space.

Failure to comply could be disastrous for a company. iFlytek, which specializes in voice recognition technology, experienced this firsthand when its AI-powered educational tablet allegedly produced a passage criticizing former leader Mao Zedong. The founder had to issue an apology, stating that associated employees and suppliers had been “penalized.” Shares plunged 10 percent in one day.

Such events elsewhere would be likely be a mere public relations blip, but in China could carry graver implications, diminishing incentives for development. Allowing black box technology like LLMs to generate speech is already a thorny problem in most societies, where there are plenty of concerns about the veracity and potential bias of the output. It is uniquely difficult in China’s hyper-sensitive environment, where speech also needs to be aligned with the Communist Party’s messaging.

In another revealing move, the government recently blocked internet access to Hugging Face, one of the major open code repositories where developers can access and work on many generative AI models collectively. This is self-sabotaging from the perspective of keeping up with cutting-edge LLM development. The fact that Beijing is willing to forego these innovation opportunities illustrates that maintaining control over its cyberspace is a higher priority than developing cutting-edge AI. This aligns with a general trend in President Xi Jinping’s third term of tackling perceived threats to national security, often to the detriment of growth.

Meanwhile, headwinds from outside the country are considerable. US export restrictions on advanced semiconductors are focused on exactly the type of high-end chips LLMs require for training. There is also talk of closing the loophole on cloud computing services such as Amazon’s AWS, which for now can still provide Chinese companies access to the same chips. The Chinese government is not at all acquiescent to this, as advanced chips are critical to all types of AI development. It is strongly protesting US restrictions while pouring resources into its own semiconductor manufacturing sector. That struggle will play out for years to come, but continued lack of access to advanced chips would eventually pose a huge deficit to R&D for generative AI in China.

What approaches are China’s AI developers taking?

In this rather discouraging climate, China’s large tech companies are taking a more pragmatic approach to generative AI services. While there are efforts to develop LLMs and other foundational models, companies generally prefer narrowly focused applications, often aimed at enterprise customers. AI developer SenseTime’s new SenseNova system features a series of task-specific tools that will aid industries from financial to marketing. Internet retailer Alibaba is experimenting with boosting its e-commerce platforms using chatbot technology.

The more commercial and application-specific approach to AI development is aligned with the government’s goals, which is much more interested in leveraging AI to transform existing industries. The 2024 Government Work Report announced an upcoming initiative, "AI Plus," that will further promote the integration of AI technology and the “real economy” – production and trade of goods and services.

Examples of this effort already abound. In the automotive industry, some of China’s autonomous driving innovations are already leading the world. In pharmaceuticals, Chinese companies are using generative AI techniques to make breakthroughs in drug discovery. Perhaps most critical to Beijing is to upgrade its manufacturing sector with smart systems in order to make up for rising labor costs and keep its competitiveness as a manufacturing powerhouse.

Viewed as part of China’s overall strategy on AI, the Chinese government's attitude towards generative AI seems to be one of measured progress rather than cutting-edge innovation: AI technologies should serve its goals of modernizing its manufacturing base and developing high-tech, higher value-add industries. Western competitors with leadership positions in industrial AI and electric vehicles should watch these efforts closely, as significant growth in Chinese exports of the “new three” – EVs, lithium batteries and solar cells – have already raised concerns. Chinese generative AI may lag behind for the now, but given Beijing’s stated focus on the real economy, this may be a price it is willing to pay.