Orbital geopolitics: China's dual-use space internet

Key findings

- China is investing massive resources into satellite internet infrastructure as part of a state-led vision for an integrated network linking land, sea, air, and space. This has been a priority since 2016, but high-bandwidth connections have come to the fore since the ascension of US Starlink.

- As a strategic, dual-use civilian and military infrastructure, satellite internet has become a focal point in global competition. China’s military was surprised by Starlink’s extensive use in the war in Ukraine, heightening the urgency to develop its own constellation.

- China’s massive investments have so far underdelivered, which explains its renewed support for private space companies. One key challenge is the high cost of launching satellites due to the lack of reusable rockets, which private firms are working to overcome. In the past, including private companies in China’s strategic technology development has sped up progress significantly.

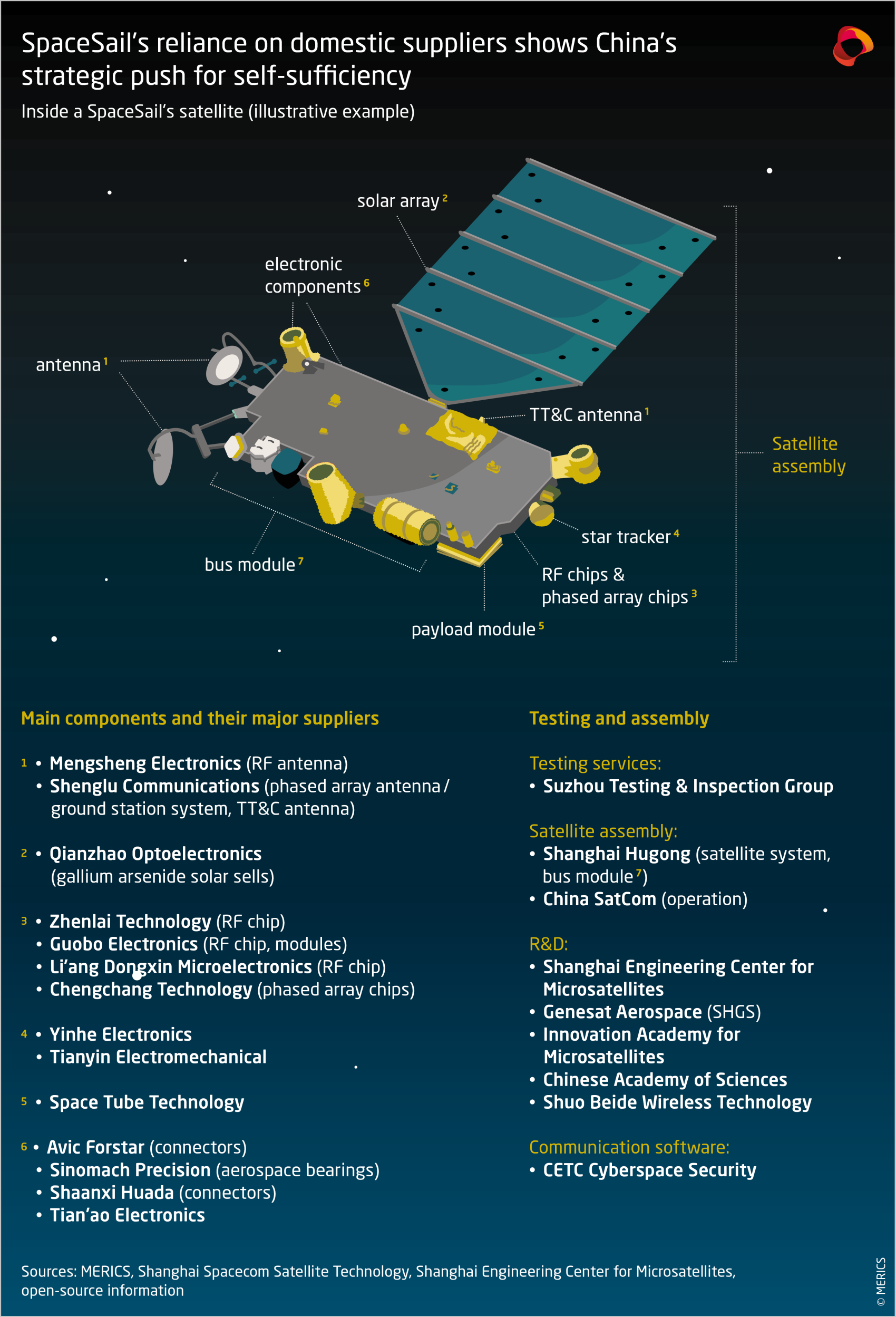

- A breakthrough in reusable rockets could quickly lead to an extensive network of deployed satellites, since China has made progress in strategic technologies and can leverage its large electronics supply chain. For radiation-hardened chips, China is basically self-sufficient, even though its technology still lags behind leading Western firms. In laser and quantum communications, Chinese firms and labs are forging ahead.

- European expertise and spectrum allocations may have contributed to Chinese advances in space-based internet. As this technology is dual-use and satellite spectrum a finite resource, European actors should take national and economic security risks more seriously and limit cooperation in this contested domain.

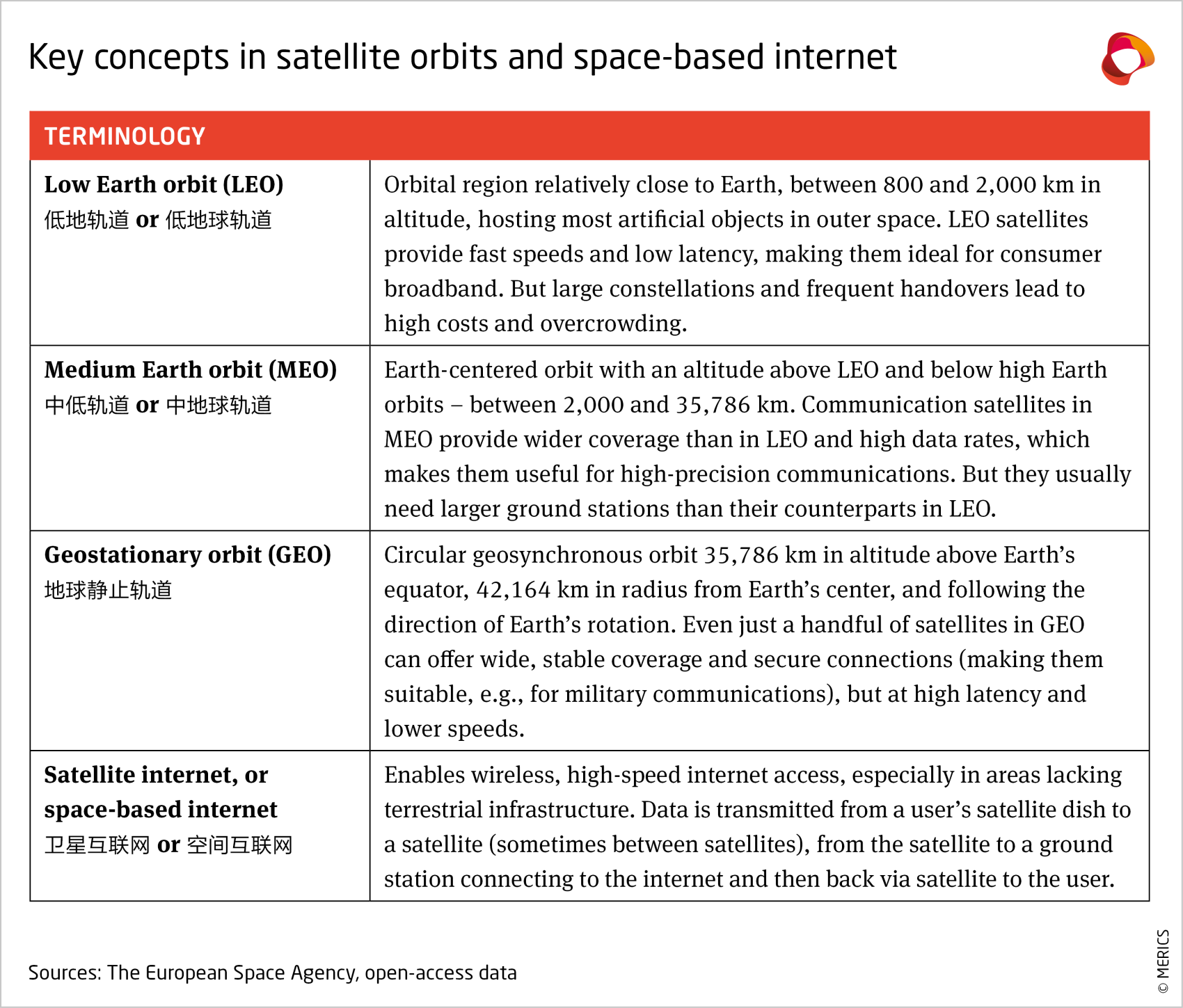

China has recognized the strategic stakes of satellite communications

Satellite internet has become a commercial and geopolitical focal point. Satellite communications promise to deliver connectivity to underserved areas, while bypassing the limitations of terrestrial networks. Concerns about the vulnerability of these critical networks have intensified since the recent sabotage of subsea cables in the Baltic Sea and the waters around Taiwan, for example.1 Satellite internet requires minimal ground infrastructure, thus offering a more resilient, reliable, and widely available option. This explains why this dual-use infrastructure is not just vital for civilian communications but increasingly also for militaries worldwide. While Russia’s war on Ukraine has exposed the pitfalls of relying on commercial providers,2 US-based SpaceX’s Starlink network of satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) offers unparalleled speed, affordability, and redundancy.

Starlink’s effectiveness and its use in Ukraine have spurred China’s military to closely study LEO as a strategic subdomain of space.3 Beijing is investing massive resources in building an independent and complete space-based internet, encompassing low, medium, and high orbits and integrating technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT). The state-led projects Qianfan (literally “Thousand Sails,” 千帆星座, also known as SpaceSail) and Guowang (“National Network,” 国网) together aim to place 27,992 broadband satellites into LEO – 15,000 and 12,992 by 2030, respectively. Additional private sector-led constellations, if successfully deployed, would bring the number to over 50,000 satellites.

But Chinese constellations are not on track to meet these lofty goals. Despite its unmatched levels of state support and a dynamic commercial ecosystem, China must overcome major technological, operational, and institutional roadblocks. However, the competitive landscape may quickly shift if its aerospace industry developed reusable rocket technology, allowing for cheaper and more frequent launches. Both private firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are working to eliminate this bottleneck while testing a range of other technologies. In addition, experts suggest that roughly 1,000 LEO satellites would be sufficient to provide basic connectivity to a small number of users across the world. Since each satellite only has limited bandwidth, Starlink needs many more to cover its over 9 million active users.4

Europe, which is home to one of Starlink’s strongest competitors, Eutelsat, and is building the IRIS² multi-orbit constellation, has a chance to step in before more countries become dependent on Chinese-controlled infrastructure for satellite connectivity as they did for traditional broadband. Concerned about SpaceX owner Elon Musk’s business interests in China, Taiwan in 2024 contracted Eutelsat to boost the resilience of its telecommunications infrastructure, considering the possibility of a military conflict with China.5 However, Eutelsat’s 650 LEO satellites cannot match Starlink’s scale of over 7,000 units.6

This report offers an overview of China’s ambitions, progress and setbacks in this domain. Key is that Beijing has a strategic vision for space internet, driven by acute national security concerns and underpinned by industrial and innovation policy. Europe should note that while China is not leading globally in satellite internet as it is in other sectors, like solar panels, underestimating this rising competitor would be a dangerous mistake.

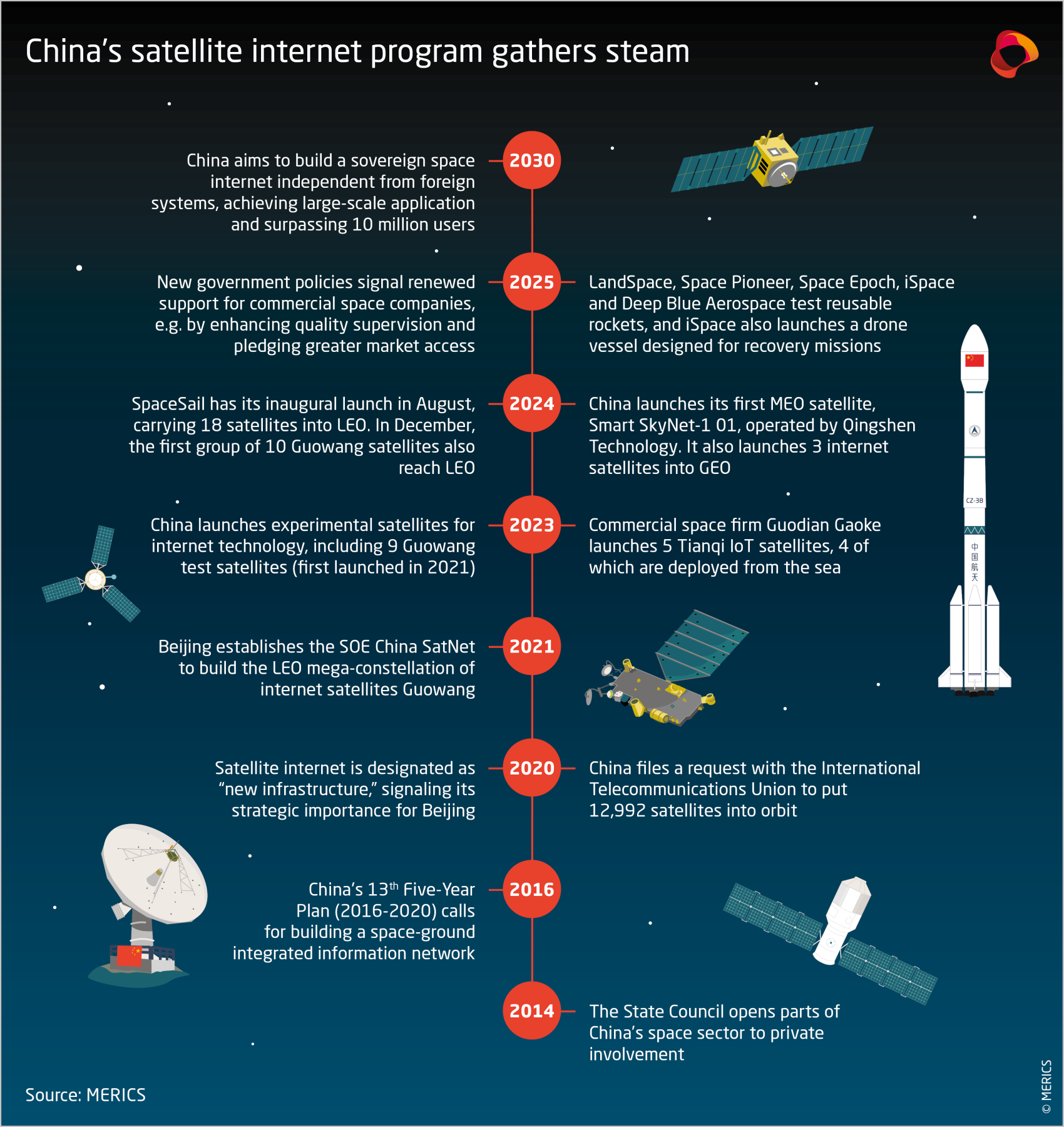

Beijing plans a self-reliant, dual-use network in space

Satellite networks are a key piece in China’s ambition to become the world’s leading space power by 2045,7 but the focus on mega-constellations, i.e., large groups of connected satellites providing internet connectivity from LEO, is relatively recent (see Exhibit 3). In 2016, Space-Ground Integrated Information Network (天地一体化信息网络) was included among the major science and technology projects in the 13th Five-Year Plan.8 It was supposed to include space-based backbone and access networks and a ground-based node network, in addition to high-altitude platforms and unmanned aerial vehicles.9 In practice, however, efforts at building constellations remained fragmented. Then, in 2020, satellite internet was designated as “new infrastructure” and Beijing stepped up support, while embracing an even grander vision for “Space-Air-Ground-Sea Integration” (空天地海一体化).10

Building a resilient satellite internet infrastructure is part of China’s goal of self-reliance in civilian and battlefield connectivity. Chinese experts suggest that while China already has “strong domestic infrastructure,” it lacks international infrastructure for “emergency scenarios” and “handling complex international situations.”11 Additionally, China’s lack of control over the ground network outside its borders is seen as a reason to invest in a space-based backbone.12 Reducing reliance on Western infrastructure has therefore become key, as it would minimize the vulnerability of China’s economic, technological, and security interests to surveillance or disruption by foreign actors. By developing its own satellite internet, China would achieve more secure, rapid, and low-latency data transmissions.

Much of this is driven by a concern over strategic vulnerabilities and perceived “orbital containment” by the United States.13 Space has been embedded in the doctrine of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) since 2015, with major investments into precision navigation and targeting under the Aerospace Force (formerly part of the Strategic Support Force).14 Although these efforts date back to the 2000s, Starlink’s rise provided a significant boost.15 PLA observers fear that Starlink could strengthen US military dominance and threaten China, for example by intercepting its missiles or engaging in electronic warfare.16

Beijing’s response has been twofold. First, PLA researchers have been exploring ways to sabotage or take down adversaries’ satellites through deliberate supply chain disruption and anti-satellite capabilities.17 Second, in 2021, the government set up the SOE China SatNet to build the Guowang constellation, which PLA analysts view as a counter to US military capabilities and activities in LEO despite the project’s ostensibly civilian nature.18 In particular, Guowang could boost China’s military’s C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) architecture by enabling high-speed, low latency and high-bandwidth communications, for instance for drones and mobile units.19

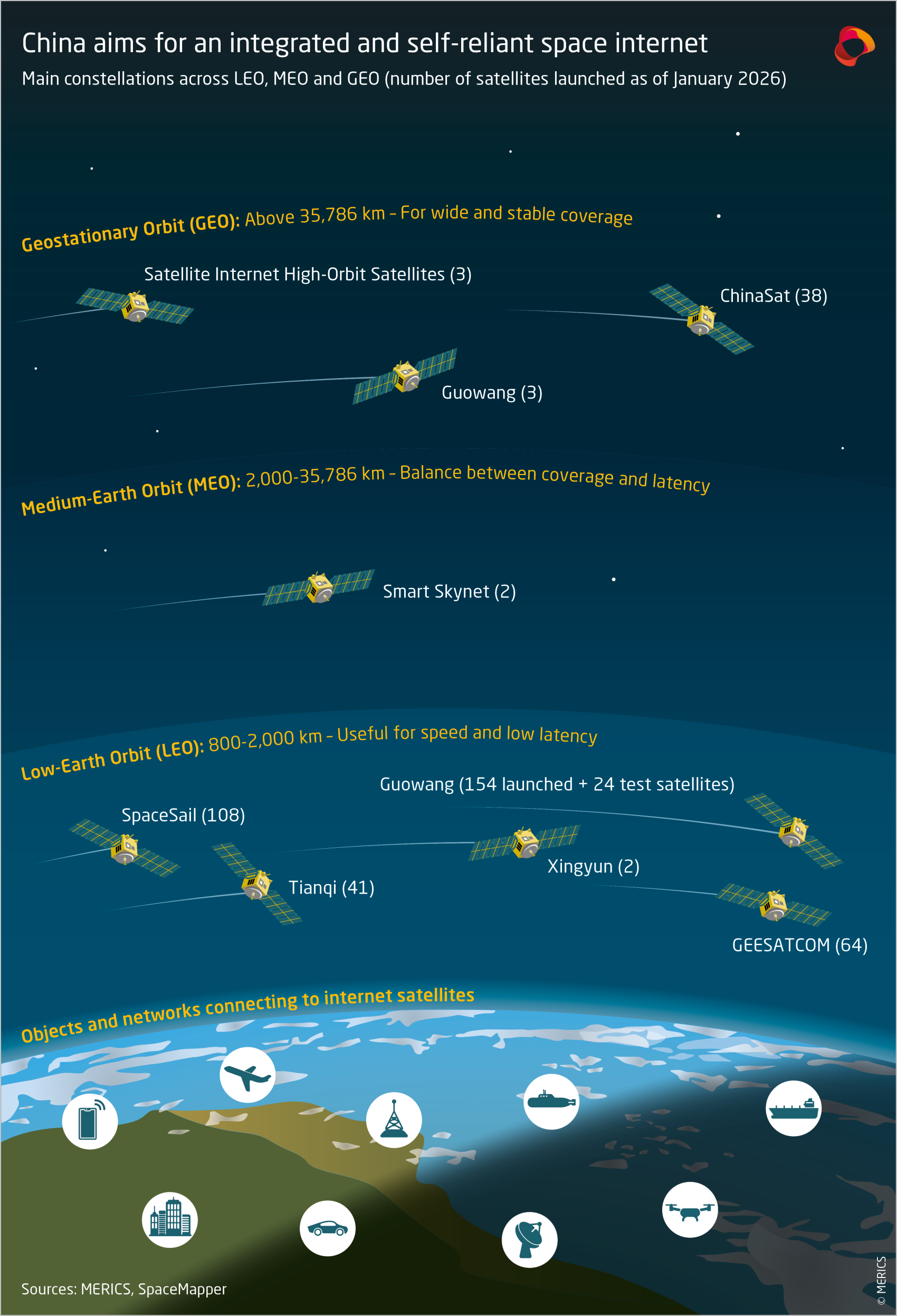

Beijing has an integrated vision for satellite internet, encompassing LEO, MEO, and GEO constellations (see Exhibit 1).20 Guowang is setting itself up to be a hybrid GEO-LEO constellation,21 with GEO relays expanding coverage even with a smaller number of LEO satellites. China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC)’s Fifth Academy, also known as China Academy of Space Technology (CAST), has launched three GEO satellites amid little transparency, strongly suggesting military involvement.22 Through its subsidiary CASC Satcom, CASC also operates the ChinaSat (中星) communication satellites in GEO. Moreover, China is slowly expanding into MEO with Smart SkyNet (智慧天网), with two satellites launched so far and 30 more planned.23

This multi-orbit strategy is supposed to pave the way for a seamless, reliable network of terrestrial and non-terrestrial layers, supporting commercial and military applications. The vision is to leverage intersatellite crosslinks, in-orbit IoT networks, and AI-powered satellites.24 Non-terrestrial networks are testing grounds for 6G technology and quantum-encrypted communication. Potential civilian uses include private communications, connected vehicles, smart factories, and smart cities.25 Moreover, a multi-orbit strategy allows the PLA to fill gaps in ground-based sensors, boosting the resilience and security of military communications through “multi-satellite networking.”26 Some Western analysts also suggest that China’s “TJS” satellites (通信技术试验) ostensibly test satellites for multi-band civilian broadcasting, likely support military and intelligence operations.27

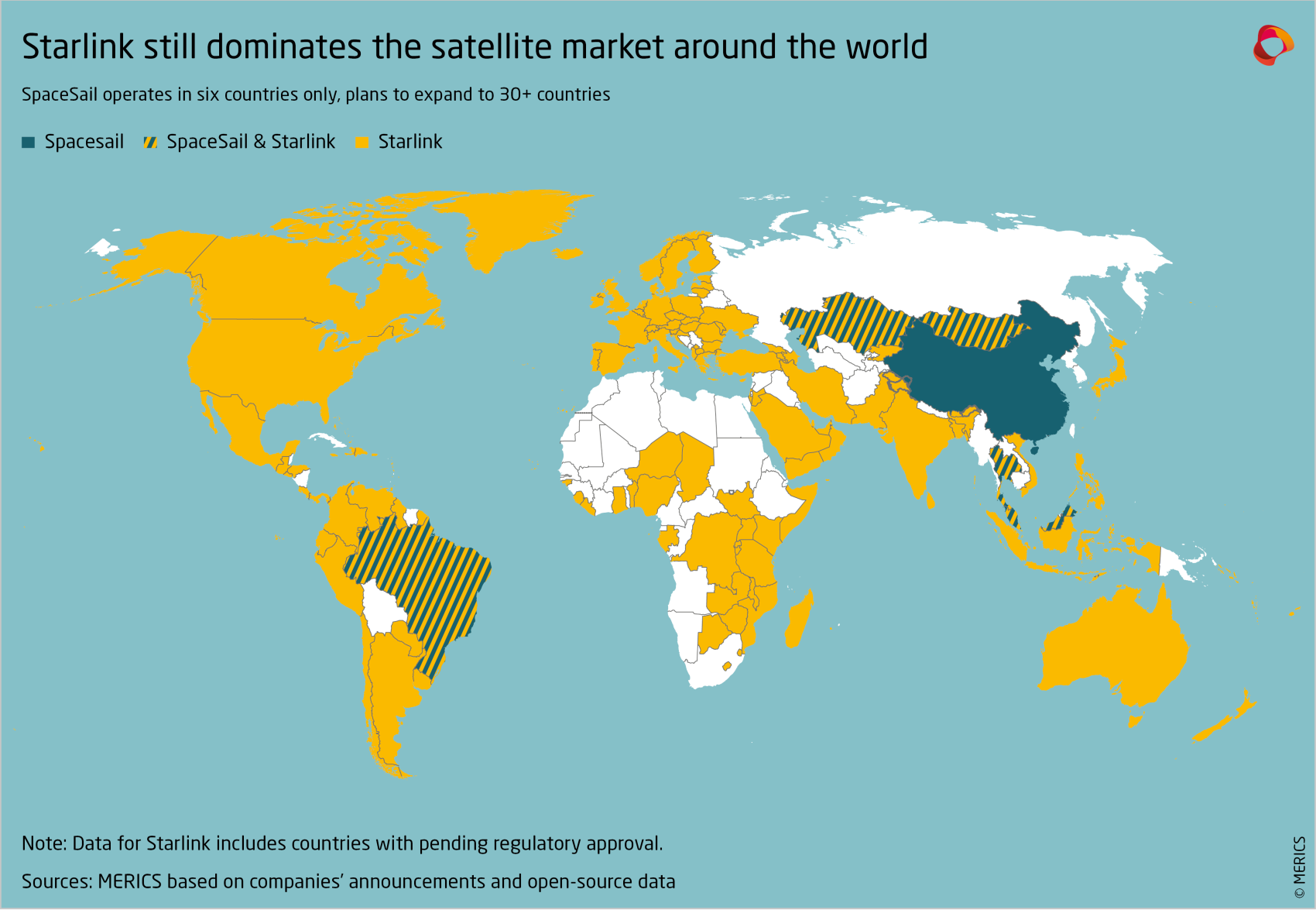

China is already fighting for the international market. On the one hand, it aims to delegitimize Starlink, arguing that its rapid expansion could block developing countries from accessing space and create “safety and security” risks.28 The Chinese government also accused Starlink of intensifying the risk of collision between satellites.29 On the other hand, China, long a laggard in the global competition for spectrum allocations, is proactively engaging at the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) to secure slots for its own constellations. It is also forging international partnerships. SpaceSail is already working with six countries, such as Brazil and Pakistan, and it aims to provide services to at least 30 more by the end of this year. For now, though, it is nowhere near the coverage of Western competitors (see Exhibit 4).

China's ecosystem still faces bottlenecks despite progress

Once a marginal player compared to Europe and the United States, China is now targeting ten million satellite communication users by 2030. In 2024, China counted three million users across all offerings, compared with Starlink’s 4.6 million users worldwide.30 With a comprehensive national strategy, heavy state investment and a vibrant private space sector, the country is making progress, and recent policies seek to speed up commercialization of satellite internet.

Two indicators of China’s progress are its manufacturing capacity and increasingly mature infrastructure. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)’s Innovation Academy for Microsatellites (微小卫星创新研究院), which makes SpaceSail’s satellites via the joint venture Shanghai Gesi Aerospace Technology (格思航天, also known as Genesat), can now produce up to 300 units per year.31 In terms of infrastructure, China has made progress in data-relay satellites, which are important communication links between Earth and space.32 On the ground, China hosts at least ten Tracking, Telemetry & Control (TT&C) stations and has access to additional stations overseas (see Exhibit 5). This ground infrastructure strengthens Chinese firms’ ability to manage their satellites while boosting China’s signals intelligence capabilities (SIGINT).33

Despite these accomplishments, China still faces significant technological and engineering challenges, limited launch capacity, as well as structural and operational constraints.

China’s satellite internet build-up is constrained by bottlenecks for state-owned firms

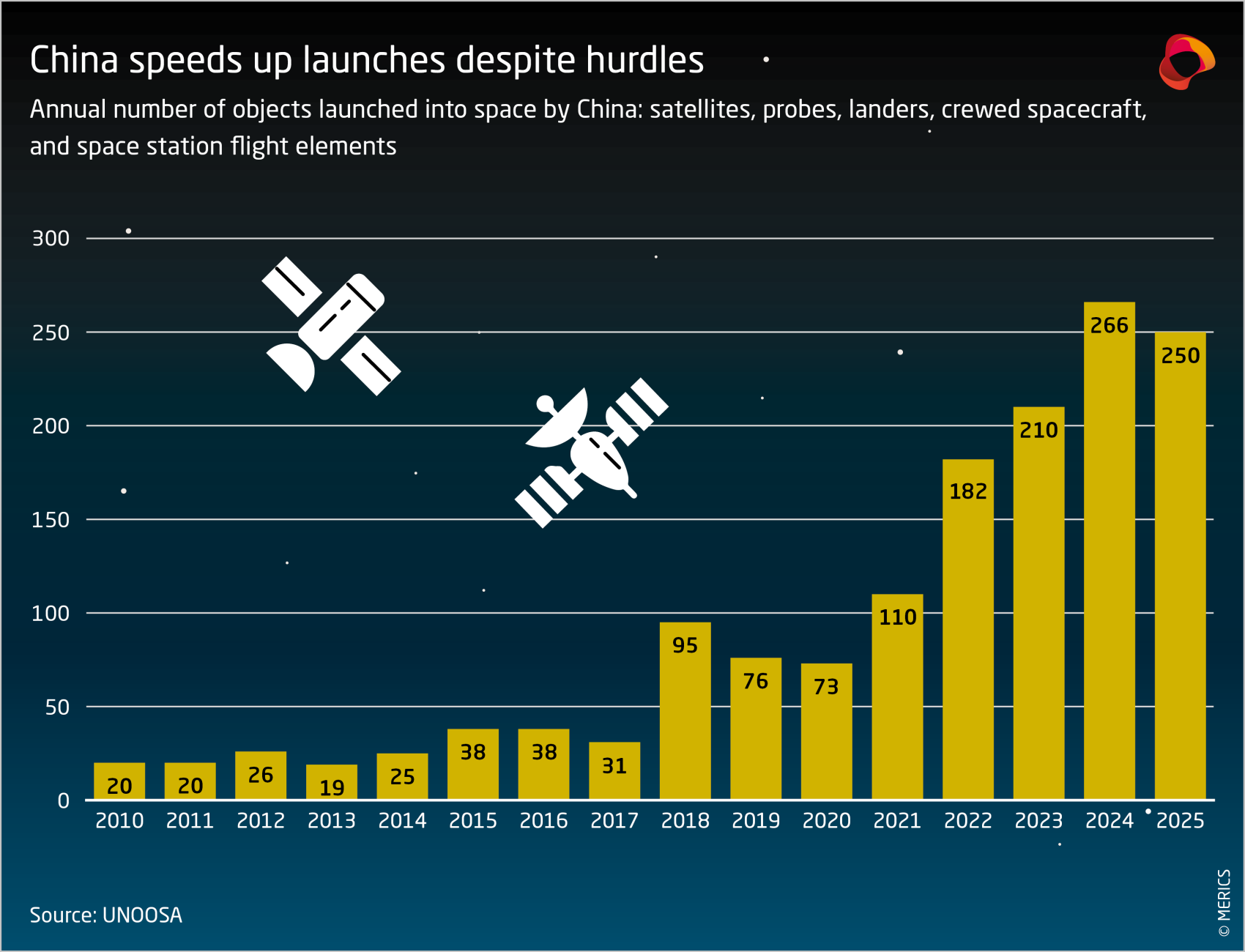

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) remain the backbone of China’s space sector. They run the Long March rocket family, BeiDou navigation satellites, and the two internet mega-constellations Guowang and SpaceSail. They also hold spectrum rights and orbital slots, giving Beijing direct control over critical space infrastructure. Between 2014 and 2015, the government officially opened the space sector to private investment and introduced its National Medium- and Long-Term Plan for Civilian Space Infrastructure (2015-2025).34 Since then, the number of satellites in orbit has grown more than eight times, reaching over 1,100 units as of August 2025.35 Many of these support satellite internet.

To deploy LEO satellites at scale, China needs speed, modularity and cost reduction, which is where private firms come in. The private sector in China is strongest in market-driven areas like reusable rockets, low-cost manufacturing of small satellites, components, and broadband services. The number of commercial space companies has increased from just 30 in 2018 to nearly 600 today.36 Until recently, private firms still faced obstacles, for example to be licensed for launches or to access national testing facilities. New policies, for example a 2025 directive to turn satellite communications into a consumer-oriented service, a new CNSA department to oversee commercial space with a two-year support plan, and an upcoming national plan for civilian space infrastructure (2026 – 2035), are expected to increase support.37

This is because SOEs cannot scale fast enough on their own. SpaceSail was scheduled to deploy around 650 satellites by the end of 2025, but deployment to date remains well below this target, with just over 100 satellites in orbit.38 To try and meet its target of 15,000-satellites in LEO by 2030, Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology (SSST), the company behind SpaceSail, is working with LandSpace (蓝箭航天),39 a private firm that is developing and testing reusable rockets (the Zhuque series, 朱雀). If commercialized, these rockets would support the launch of 10 to 18 satellites at a time. Guowang is also far from meeting its target: only a small share of its planned constellation is in orbit.40 The latest batch was designed and built by GalaxySpace (银河航天), another private company.41

Private ventures are also developing their own constellations. Two notable projects are Honghu-3 (鸿鹄-3) by LandSpace-backed Hongqing Technology (鸿擎科技) and Geely’s Future Mobility Constellation (吉利星座, or GEESATCOM), which aim to put into orbit around 16,000 satellites combined.42 The IoT network Tianqi (天启), a planned constellation of nearly 4,000 satellites, is being developed by Guodian Gaoke (国电高科), another private enterprise.43 These projects are still in their initial stages, and their intended use-cases are not always clear.

Satellite internet ventures rely heavily on state capital

China’s commercial space sector is heavily funded by state capital, with private capital playing an important but supporting role. According to Orbital Gateway Consulting, an authoritative source, total investment reached about CNY 21 billion (approximately EUR 2.5 billion) in 2024, and investment in launch companies reached a record of CNY 8 billion (EUR 966 million) in 2025.44

Through own analysis of an original dataset of 100 Chinese space-related companies from Chinese data provider ITjuzi, we found that about 48 percent of funding rounds involved direct government sources, while 50 percent involved state-linked venture capital (VC) or private equity (PE) investors.45 Only 24 percent of firms in our sample did not disclose any state-linked funding. Even firms that appear to have no state investors often have indirect investment, for example through limited partnerships with private VC/PE.46 This suggests government influence is strong even in ostensibly private funding.

Core segments such as satellite manufacturing and ground systems are funded largely by the state. Rocket and component manufacturing, remote sensing, and navigation services increasingly rely on the private sector for funding.47 With few exceptions, smaller players work as subsystem providers rather than full constellation operators. Most also remain structurally tied to the state through funding and policy alignment.

State support comes from the central government, local governments, and banks. In March 2025, the government created a national venture capital fund and is also expanding its technology-specific lending program from CNY 500 billion to between CNY 800 billion and 1 trillion through the People’s Bank of China.48 Other banks have provided funding, for example for iSpace's (星际荣耀) Hyperbola rockets and LandSpace’s Zhuque series.49 Local governments support space firms via mechanisms such as subsidies, tax incentives, loans, and spaceports.50 Beijing’s Haidian District, for example, is planning a CNY 100-billion industrial cluster for 200 commercial aerospace companies,51 while Shanghai’s government is offering CNY 300 million in subsidies.52

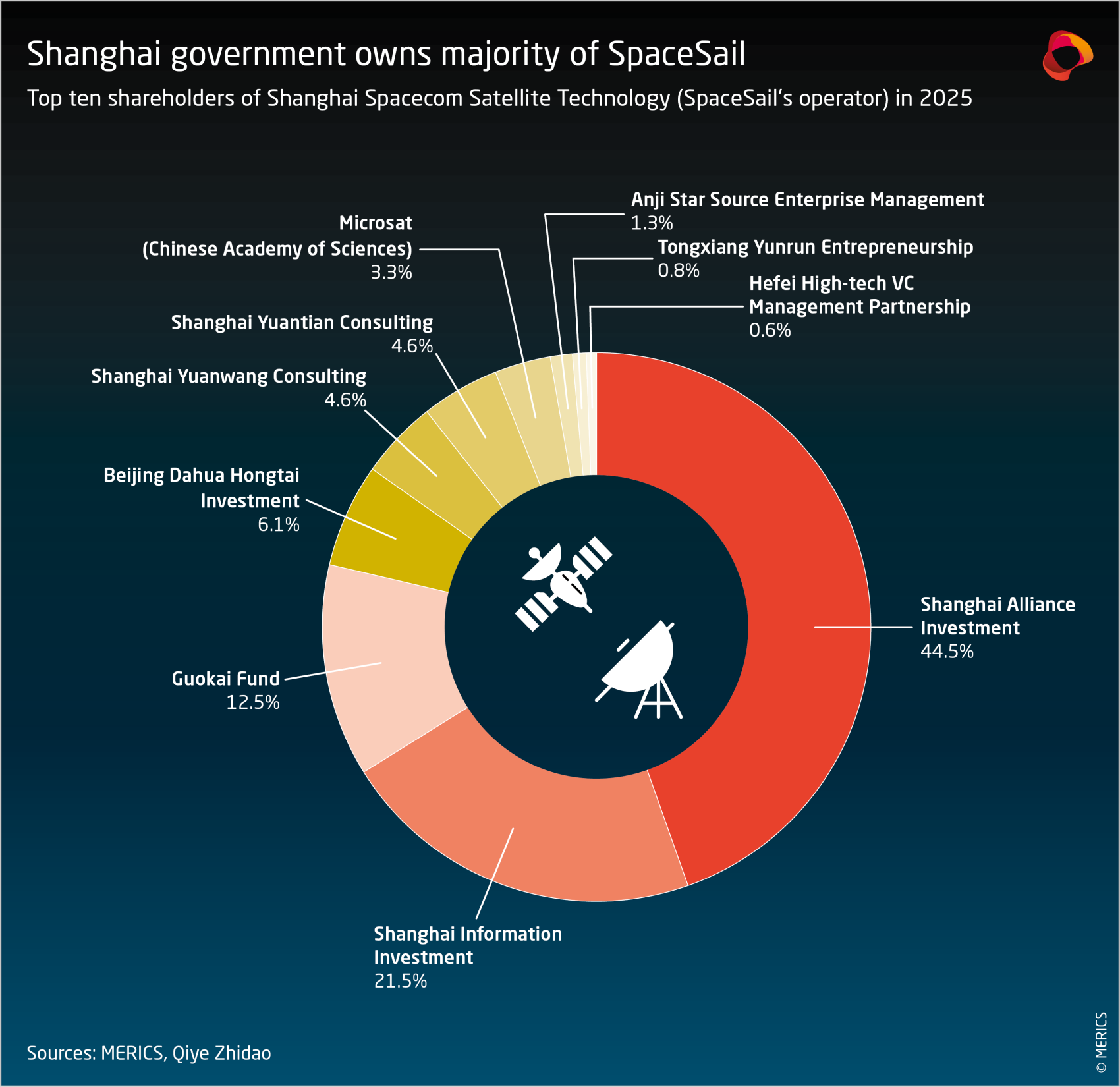

Private firms and state-linked venture capital have also funded China’s satellite projects. The state-controlled SSST (see Exhibit 6) raised CNY 6.7 billion (EUR 900 million) in 2024 to develop SpaceSail, including from private investors alongside state-owned funds like CAS Star.53 iSpace, a private rocket developer, is backed by venture investors such as HongShan Capital Group, as well as by state-linked funding from Chengdu. Overall, the role of private investors is dwarfed by state capital.

China still lacks a reusable rocket

The technology behind LEO systems requires complex engineering, from satellite design and propulsion to orbital mechanics and communications. Unlike traditional geostationary satellites, LEO satellites circle the Earth in 90 minutes at 17,000 miles per hour. This needs inter-satellite links, software, and reliable ground terminals – areas where China is still at the early stage of development. China’s main bottleneck, however, lies in its limited launch capacity.

Since rockets are expensive and can only carry small payloads, deployment remains slow. Even with 100 satellites ready, if a launcher carried only 10 – 18 per flight, it would take months to get them into orbit. The problem is pressing: To keep their full spectrum rights with the ITU, Guowang and SpaceSail must each have at least ten percent of their planned networks in orbit by the end of 2026. With only about 260 LEO satellites launched so far, the two combined must deploy over 2,600 within a year, an impossible target; in 2025, they launched just 180 satellites altogether (see Exhibit 7).

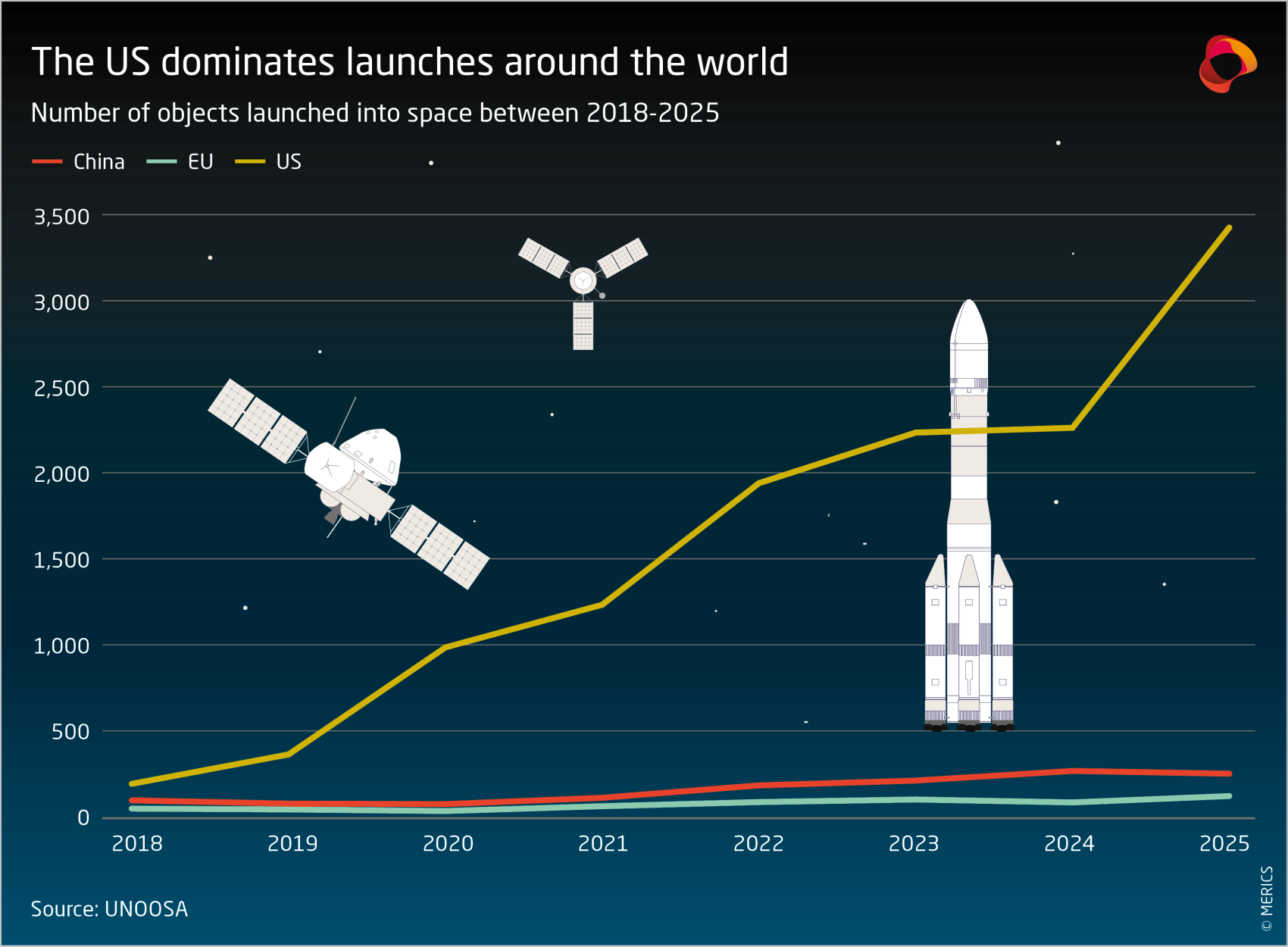

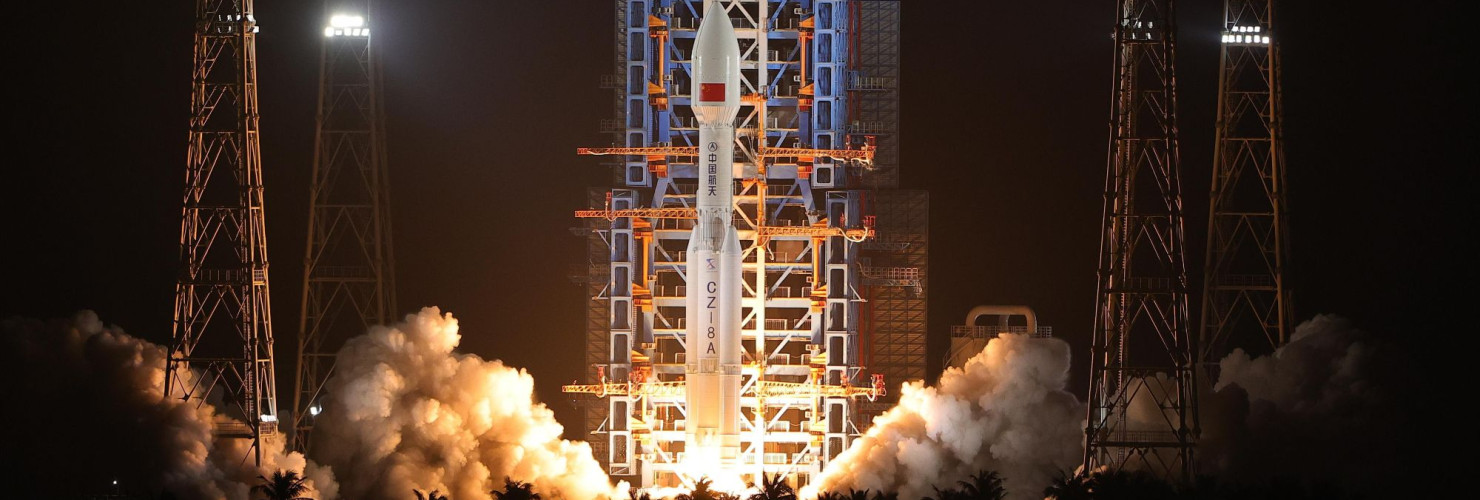

The chokepoint here is the lack of a reusable rocket. SpaceX’s reusable Falcon series has allowed the company to significantly cut launch costs and increase launch frequency. By contrast, China relies on the single-use Long March rockets, which makes launches expensive.55 The launch cost in China is about CNY 150,000 (ca. USD 21,000) per kilogram. By comparison, SpaceX’s launches cost USD 2,700-3,000 per kilogram aboard a Falcon 9, about 94 percent cheaper. Starlink’s next-generation rocket, Starship, could drop costs to USD 13 – 32 per kilogram.56 The US experience shows that launches sped up significantly once the reusable rocket became ready.

This gap explains why SOEs see reusable rockets as a promising solution. A host of private firms, such as LandSpace, iSpace, Galactic Energy (星河动力), Space Pioneer (天兵科技), Space Epoch (箭元科技), and Deep Blue Aerospace (深蓝航天), as well as the state-owned CASC are all prototyping reusable rockets.57 In 2023, LandSpace launched a methane-fueled rocket and is currently developing and testing a reusable stainless-steel rocket, the Zhuque-3.58 Progress has been limited, however, with many companies surviving only for a short time. The number of rocket companies in China decreased from 49 in 2019 (of which 8 SOEs) to 35 (3 SOEs) as of July 2025.59

Some of China’s hurdles may be due to structural and operational challenges. Reliance on SOEs for orbital slots and spectrum allocation creates limitations for the private sector. Overlapping bureaucracies also limit efficiency: Firms rely on China Great Wall Industry Corporation to work with international contracts, which must pass through layers of red tape.60 Regulations are still incremental and lack clarity around spectrum rights, licensing, and market priorities (see Exhibit 8).

China is testing new technologies

China’s private space sector is taking on a larger role in strategic domains, for example relay systems that manage data flows in LEO and beyond. Several companies are also researching and testing new technologies that could eventually transform commercial and military applications. Many of these are still at the prototype stage, but it is a matter of time before some reach industrial scale.

Radiation-hardened chips: Western export controls galvanized localization in China

China has progressed toward self-reliance in developing radiation-hardened (rad-hard) chips, boosted by US restrictions. These chips are needed in rockets, spacecraft and satellites because of the higher levels of ionizing radiation present in space. According to the chief scientist on CASC’s rad-hard program, US export controls61 incentivized Chinese scientists to develop alternatives.62 Chinese technology still lags that of Western firms such as BAE Systems and Microchip Technology, and commercialization remains difficult due to limited scale.63 Still, China has localized most core components for its satellites.64

Several players are researching and developing rad-hard integrated circuits. The CAS Institute of Microelectronics houses a State Key Laboratory for rad-hard technology.65 In early 2025, its researchers validated high-voltage rad-hard silicon carbide chips on the Tianzhou-8 cargo spacecraft.66 The other pioneer is the Beijing Micro-Electronics Technology Co. (CASC 772 Institute), whose chips are used in the core module of China’s space station.67 Two smaller players are Sunwise Space (CASC 552 Institute) and Loongson.68

Chinese scientists are also working on networking technologies for satellite communications. For example, Pengcheng Laboratory and the Harbin Institute of Technology verified a new antenna for improved signal and satellite tracking in LEO.69 Another promising area is the use of laser technology to speed up data transmissions between and from satellites. In 2024, China achieved a 100 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) satellite-to-ground optical transmission. About a year later, Laser Starcom (极光星通) made headlines for transmitting data between two satellites at 400 Gbps using lasers, twice the current capacity of Starlink. The company is now eyeing mass manufacturing of its laser terminals.70

Quantum communications are the next frontier, and one where China is well positioned to overtake. The country has been building a satellite-based quantum communication network across LEO and MEO, including the first 10,000 km quantum-secured link between Beijing and South Africa in March 2025.71 Pan Jiawei, a leading quantum physicist, is also spearheading efforts to develop GEO-based quantum platforms, with a plan to launch China’s first high-orbit quantum communication satellite in 2027.72 Since GEO satellites maintain a fixed position above Earth, they can provide larger and uninterrupted coverage for military and civilian applications.

These developments support national security and commercial goals, paving the way for space-based 6G communications independent of Western infrastructure. Tech giant Huawei is working on LEO and Very-Low-Earth-Orbit (VLEO) satellite communications.73 In 2024, the company started testing its first 6G satellite, reportedly developed entirely with Chinese hardware and software.74 Successful deployment of 6G satellites could provide China with a strategic advantage in global communications, with potential military applications such as operational coordination and precision targeting.

High-risk cooperation: Europe learned its lesson the hard way

Until recently, the strategic and national security implications of satellite internet infrastructure were rarely discussed outside the defense and intelligence communities in Europe. China, moreover, was largely not seen as posing direct security challenges to the EU. That geopolitical context allowed for several cooperation initiatives between European and Chinese commercial actors in LEO. The subsequent setbacks or suspension of those projects offer lessons regarding the importance of risk assessments prior to any collaboration with China-based partners on critical space technology or infrastructure.

The failure of KLEO Connect, a joint venture (JV) between a German startup, a US-based firm, and state-linked Chinese investors, demonstrates how the European side might have underestimated the strategic significance of satellite communications. KLEO Connect, which has since gone bankrupt, was created in 2017 by Western partners and SSST, the company behind SpaceSail, to launch more than 300 internet satellites in LEO by 2028. The JV ended in legal disputes, with the German partner accusing the Chinese side of sabotaging the project by trying to use its spectrum allocation to build its own constellation.75 SSST has disputed the accusation.76

The case highlighted the geopolitical competition around the allocation of space in orbit. In 2021, the Shanghai Engineering Center for Microsatellites, the manufacturer for KLEO Connect’s constellation and SSST’s shareholder, launched two LEO satellites with the same technical specifications, orbital slot and frequency range of the JV’s planned deployment – unbeknown to its European partners.77 There are still ongoing disputes on the frequency allocation registered to KLEO Connect in Liechtenstein.78

Another high-risk collaboration was a partnership between the French propulsion startup ThrustMe and the Chinese micro- and nano-satellite maker Spacety. In 2020, Spacety (officially Changsha Tianyi Space S&T Research Institute, 长沙天仪空间科技研究院) launched the world’s first iodine-propelled satellite.79 Iodine is cheaper and easier to use compared to other propellants like xenon.80 Though the collaboration focused on applications in airplane tracking and remote sensing, electric ion thrusters can make small satellites more maneuverable, thus limiting collisions that would produce even more space debris in the already crowded LEO.81

Despite the potential benefits, ThrustMe’s collaboration with Spacety also raised clear national security concerns. Spacety, whose Luxembourg subsidiary has since filed for bankruptcy, was hit by US and EU sanctions for providing satellite imagery of locations in Ukraine to assist the mercenary Wagner Group in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.82 It is unclear whether Beijing, which has been supporting Russia’s war in Ukraine, was aware of those activities. Spacety is also known for its work on air defense radar.83

As the strategic relevance of space is growing, and more European countries increasingly view China as a security challenge, scrutiny of such collaborations has fortunately increased. A plan by OneWeb to enter the Chinese market never materialized, and the stake of a Chinese sovereign wealth fund was reduced to two percent when the company merged with Eutelsat in 2022.84 In Germany, the government in recent years barred a laser tech company from operating in China and blocked the takeover of another satellite communications firm by the Chinese state.85

Given China’s strategic and geopolitical ambitions, any collaboration should be vetted thoroughly, provide clear benefits to European stakeholders, and include safeguards to ensure that no technology or know-how is compromised in ways that could jeopardize economic or national security.

European constellations are ahead but need scale to compete

China’s progress in satellite internet does not yet match its ambitions. While Starlink galvanized Chinese efforts, the country still struggles to execute. However, Starlink’s extensive use in Ukraine is now spurring the PLA to put its weight behind the technology. Technical hurdles, especially insufficient launch capacity, add to regulatory hurdles and the traditional dominance of SOEs.

China has been trying to expand the role of commercial companies in space, drawing lessons from the US. However, the dual-use nature of space technologies and entrenched SOEs make the US commercial model inapplicable, especially as China is still lacking completely private funding. Still, the agility and innovativeness of private firms make them indispensable, which likely explains why Beijing is signaling renewed policy support.

But China has some advantages. The country is strong at scaling up manufacturing and is a major production hub for the electronics required for satellites and ground terminals. Chinese companies have a history of taking advantage of being second movers. Due to its highly regulated internet, moreover, Chinese firms will not need to worry about competition from Starlink.

China’s extensive ties to lesser developed and emerging markets and its experience as a connectivity provider could enable it to establish a footprint quickly, as the country did in terrestrial network equipment like 5G base stations. Lacking affordable alternatives, many developing countries might well choose SpaceSail’s services, especially if they can integrate into existing 5G/6G offerings. While this prospect could narrow the global digital divide, it would also embed countries into China’s state-controlled, dual-use information infrastructure.

Even though China is currently not meeting its ambitions, Europe would do well to take the challenge it poses seriously. A Chinese satellite internet with global coverage could deepen global dependencies on China for digital connectivity, and Europe risks being left behind. In addition, Beijing’s extensive support and huge ambitions, demonstrated again at the end of 2025 with its ITU spectrum filings for over 200,000 satellites, are unlikely to completely evaporate. The country is already in a favorable position as an electronics manufacturing hub, and in other technologies inclusion of the private sector has led to significant breakthroughs for China. In satellite internet, breakthroughs in reusable rockets could significantly speed up satellite deployment.

This critical infrastructure requires a strategic approach. While Europe’s first concern is its reliance on Starlink, China’s activities also have implications for Europe. Satellite internet could boost the PLA’s capabilities in areas such as optical-radar fusion, precise signals, and quantum-encrypted communications. While not covered in this report, China’s counterspace capabilities are also a cause for concern. The new German government strategy for space safety and security notably singles out China for having demonstrated capabilities to destroy or sabotage foreign satellites.86

Europe is yet to capitalize on its strengths in network technology, which could be expanded into satellite internet. For example, it is a major player in laser communications. In terms of regulation, however, market fragmentation keeps holding the continent back. In addition, Europe struggles with funding and scale for similar projects, as demonstrated by repeated failures at building an independent cloud ecosystem. European alternatives to Starlink need to be competitive or to provide a unique selling point to attract users.

Like China, Europe is also dealing with insufficient launch capacity. The European Space Agency’s new European Launcher Challenge is supposed to replicate the model that the US successfully used to build capacity with SpaceX, Amazon, and Boeing. The winners must achieve an orbital launch no later than 2027, after which ESA will commit to procuring their launch services for its missions.

Recommendations

- Monitor Chinese advances in satellite internet: China’s forays into space-based communications carry economic, geopolitical, and security implications. Relevant actors in Europe should systematically track China’s activities and technological progress, including by building on EU-led efforts87 to monitor space value chains.

- Invest in European satellite internet services for civilian and military applications: European startups paved the way for the new space economy, but Europe’s capacity in space-based internet is eclipsed by SpaceX’s. Europe should treat space-based internet as it did with satellite navigation and build its own networks.

- Consolidate the market, focus on launch capacity: China’s experience shows that even with ample policy and funding support, insufficient launch capacity can hinder constellations’ deployment. European efforts should be efficient, targeted, and seek to remedy the fragmentation of Europe’s space and internet markets.

- Foster European innovation and supply chain resilience: EU incentives for innovators in critical space technologies, like lasers, are crucial for keeping the industry competitive. These efforts should be accompanied by supply chain resilience measures, especially in critical minerals like gallium and rare earth elements where Europe relies on Chinese suppliers.

- Consider access to space as a security priority: As LEO becomes increasingly crowded, it is now a more contested area where adversarial actors can restrict European access, either intentionally or otherwise.88 China’s potential access to spectrum around Europe should be considered a potential indirect threat to European security.

- Review all cooperation agreements with China and limit them in areas of strategic concern: Cooperation in such a strategic technology area as space poses considerable risk. In areas of shared concern, like mitigating space debris, there could be opportunities for selective, highly scoped engagement.

- Consider offering affordable access to lesser developed countries: European companies are already competing with SpaceSail across markets from Central Asia to Latin America. European governments should consider ways to embed satellite internet within the EU’s connectivity partnerships.

- Endnotes

1 | Ogryzko, Lesia and Alberto Rizzi (2025). “Shallow seas and “shadow fleets”: Europe’s undersea infrastructure is dangerously vulnerable.” ECFR. April 8. https://ecfr.eu/article/shallow-seas-and-shadow-fleets-europes-undersea-infrastructure-is-dangerously-vulnerable/. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Ewe, Koh and I-ting Chiang (2025). “Taiwan jails China captain for undersea cable sabotage in landmark case.” BBC. June 12. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cwy3zy9jvd4o. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

2 | Balmforth, Tom (2025). “Musk ordered shutdown of Starlink satellite service as Ukraine retook territory from Russia.” Reuters. July 25. https://www.reuters.com/investigations/musk-ordered-shutdown-starlink-satellite-service-ukraine-retook-territory-russia-2025-07-25/. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

3 | International Cooperation Center 国际合作中心 (2023). ““星链”军事化发展及其对全球战略稳定性的影响” (The Militarization of Starlink and Its Impact on Global Strategic Stability). September 24. https://web.archive.org/web/20250412021224/https://www.icc.org.cn/strategicresearch/laboratory/internationalsecurity/xgwz/1954.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Wang, Howard, Jackson Smith and Cristina L. Garafola (2025). “Chinese Military Views of Low Earth Orbit - Proliferation, Starlink, and Desired Countermeasures.” RAND. March 24. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3139-1.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

4 |Forrester, Chris (2026). “Starlink exceeds 9.2m customers.” Advanced Television. January 5. https://www.advanced-television.com/2026/01/05/starlink-exceeds-9-2m-customers/. Accessed: 06.01.2026.

5 | Davidson, Helen (2024). “Taiwan to have satellite internet service as protection in case of Chinese attack.” The Guardian. October 15. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/oct/15/taiwan-to-have-satellite-internet-service-as-protection-in-case-of-chinese-attack. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Wang, Joyu, Micah Maidenberg and Yang Jie (2024). “Taiwan’s Race for Secure Internet Detours Around Musk’s Starlink.” The Wall Street Journal. October 30. https://www.wsj.com/tech/taiwans-race-for-secure-internet-detours-around-musks-starlink-7c273912. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

6 | Hille, Kathrin (2024). “Taiwan in talks with Amazon’s Kuiper on satellite communications amid China fears.” Financial Times. December 17. https://www.ft.com/content/cbbcf94b-d326-4edd-b926-8a91d5297df8. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

7 | Chi, Ma. China Daily (2017). “China aims to be world-leading space power by 2045.” November 17. https://web.archive.org/web/20230328123304/https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-11/17/content_34653486.htm. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

8 | National Development and Reform Commission 发改委 (2016). “中华人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十三个五年规划纲要” (Outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China). https://web.archive.org/web/20220131142913/https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/ghwb/201603/P020190905497807636210.pdf. Accessed: 03.11.2025.

9 | Ibid.

10 | Huaxin Consulting 华信咨询 (2021). “头条看点丨空天地一体化信息网络真的要来了吗?” (Headline Highlights | Is an Integrated Space-Air-Ground Information Network Really Coming?). Retrieved via WeChat. June 25. https://archive.ph/vFVSy. Accessed: 11.11.2026.

11 | Xu, Xiaofan 徐晓帆, Niwei Wang王妮炜, Yingyuan Gao 高璎园 et al. (2021). “陆海空天一体化信息网络发展研” Development of Land–Sea–Air–Space Integrated Information Network.” Strategic Studies of CAE 23(2): 39-45. May 14. https://doi.org/10.15302/J-SSCAE-2021.02.006. Accessed: 03.11.2025.

12 | Ibid.

13 | Nanping Yu 余南平and Jiajie Yan 严佳杰 (2024). “国际和国家安全视角下的美国“星链”计划及其影响” (The U.S. Starlink Project and Its Implications from the Perspective of International and National Security). Journal of International Security Studies. Retrieved from China Institute of Command and Control. September 14. https://archive.ph/p7rbV. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

14 | China’s State Council (2015). “China’s Military Strategy.” May 27. https://web.archive.org/web/20251023035037/https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

15 | Wang, Howard, Jackson Smith and Cristin L. Garafola (2025). “Chinese Military Views of Low Earth Orbit - Proliferation, Starlink, and Desired Countermeasures.” RAND. March 24. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3139-1.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

16 | Nanping Yu 余南平and Jiajie Yan 严佳杰 (2024). “国际和国家安全视角下的美国“星链”计划及其影响” (The U.S. Starlink Project and Its Implications from the Perspective of International and National Security). Journal of International Security Studies. Retrieved from China Institute of Command and Control. September 14. https://archive.ph/p7rbV. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

17 | Burke, Kristin (2023). “PLA Counterspace Command and Control.” CASI. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Research/PLASSF/2023-12-11%20Counterspace-%20web%20version.pdf. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

18 | Julienne, Marc (2023). “China in the Race to Low Earth Orbit: Perspectives on the Future Internet Constellation Guowang.” Ifri. April 27. https://www.ifri.org/en/papers/china-race-low-earth-orbit-perspectives-future-internet-constellation-guowang. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Wang, Howard, Jackson Smith and Cristin L. Garafola (2025). “Chinese Military Views of Low Earth Orbit - Proliferation, Starlink, and Desired Countermeasures.” RAND. March 24. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3139-1.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

19 | Cheng, Dean (2021). “Space and Chinese National Security: China’s Continuing Great Leap Upward.” In: Wuthnow, Joel et al. The PLA beyond borders. Chinese Military Operations in Regional and Global Context, pp. 311-330. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/beyond-borders/990-059-NDU-PLA_Beyond_Borders_sp_jm14.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

20 | Huaxia 华夏 (2021). “十四五”期间我国将加快布局卫星通信” (During the 14th Five-Year Plan period, China will accelerate the deployment of satellite communications). November 22. https://web.archive.org/web/20250812124147/https:/www.huaxia.com/c/2021/11/22/888353.shtml. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

21 | Zhihu 知乎 (2025). “长征六号甲年度第5飞为中国星网再添5星!” (The fifth Long March 6A launch of the year adds five more satellites to China's satellite network!). July 30. https://archive.ph/L0qjx. Accessed: 11.11. 2025.

22 | Sina 新浪 (2024). “独家:我国首颗正式卫星互联网高轨卫星!这才是重大看点!” (Exclusive: China's First Official Satellite Internet Geostationary Orbit Satellite! This Is the Real Highlight!). March 1. https://archive.ph/zFMz1. Accessed: 11.11.2025; China Satellite Communications Co. 中国卫通集团股份有限公司 (2025). “中星10R成功发射!我国高轨卫星通信能力持续增强” (Zhongxing-10R successfully launched! China's high-orbit satellite communication capabilities continue to strengthen). https://archive.ph/kDTmJ. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Ma, Shuaisha马帅莎 (2025). “中国成功发射中星10R卫星助力共建“一带一路”” (China successfully launches Zhongxing-10R satellite to support the Belt and Road Initiative). Ifeng. February 23. https://web.archive.org/web/20260114185539/https://i.ifeng.com/c/8hBU3UCfXwh. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

23 | Tsinghua University 清华大学 (2024). “智慧天网一号01星成功发射!” (Sky Net-1 Satellite 01 Successfully Launched!). May 9. https://archive.ph/U8PJL. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

24 | People’s Daily Online (2025). “Chinese space firm deploys IoT satellite constellation for global coverage.” September 25. https://web.archive.org/web/20250925092113/https://en.people.cn/n3/2025/0925/c90000-20370916.html . Accessed: 28.10.2025.

25 | Ibid.

26 | Xinhua 新华 (2021). “卫星互联网:高科技领域的低成本挑战” (Satellite Internet: The Low-Cost Challenge in a High-Tech Field). July 19. https://web.archive.org/web/20240310013510/https://www.xinhuanet.com/tech/20210719/da3c70bfbffe46758a1672659fb5ec5e/c.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

27 | Smid, Henk (2022). “An analysis of Chinese remote sensing satellites.” The Space Review. https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4453/1. Accessed: 11.11.2025; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2025). “Hearing on the Rocket’s Red Glare: China’s Ambitions to Dominate Space.” April 3. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2025-04/April_3_2025_Hearing_Transcript.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

28 | Hitchens, Theresa (2023). “At UN meeting, space cooperation picks up momentum, but Moscow and Beijing play spoilers.” Breaking Defense. February 3. https://breakingdefense.com/2023/02/at-un-meeting-space-cooperation-picks-up-momentum-but-moscow-and-beijing-play-spoilers. Accessed: 11.11.2025; South China Morning Post (2026). “China warns satellites from Elon Musk’s Starlink are ‘safety and security’ risk.” January 1. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3338409/china-warns-satellites-elon-musks-starlink-are-safety-and-security-risk. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

29 | UN General Assembly (2021). “Information furnished in conformity with the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.” December 6. https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2021/aac_105/aac_1051262_0_html/AAC105_1262E.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Ministry of Foreign Affairs China (2022). “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference on February 10, 2022.” February 10. https://web.archive.org/web/20260114193633/https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/fyrbt/lxjzh/202405/t20240530_11347221.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

30 | MIIT 工信部 (2025). “工业和信息化部关于优化业务准入促进卫星通信产业发展的指导意见” (Guiding Opinions of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology on Optimizing Business Access to Promote the Development of the Satellite Communications Industry). August 27. https://archive.ph/9u2sq; China Baogao 报告大厅 (2025). “2025年中国卫星通信市场新纪元:互联网融合与千万级用户目标达成路径解析.” August 28. https://archive.ph/IMENH. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Business Insider (2025). “Elon Musk's Starlink is adding 20,000 new users a day as it hits 9 million customers.” https://www.businessinsider.com/spacex-starlink-customer-numbers-surge-9-million-elon-musk-ipo-2025-12. Accessed: 11.01.2026.

31 | Innovation Academy for Microsatellites of Chinese Academy of Sciences 中国科学院微小卫星创新研究院. https://archive.is/yqZ8q. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

32 | ST Daily 中国科技网 (2024). “我国首次!星地100千兆比特每秒激光通信试验完成” (My country's first-ever 100 gigabits-per-second laser communication experiment between space and ground completed!) December 28. https://web.archive.org/web/20250102185514/https://www.stdaily.com/web/gdxw/2024-12/28/content_280059.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Sina 新浪 (2025). “速率提升75%!我国高阶体制高码率星地通信地面技术实验成功” (A 75% increase in speed! my country successfully conducts high-speed, high-bit-rate satellite-to-ground communication terrestrial technology experiment). May 26. https://web.archive.org/web/20260114201409/https://finance.sina.com.cn/tech/roll/2025-05-26/doc-inexwxma9771530.shtml. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

33 | Boyd, Henry, Erik Green and Meia Nouwens (2025). “Space: China’s TT&C capabilities and space diplomacy.” IISS. July 17. https://www.iiss.org/charting-china/2025/07/space-chinas-ttc-capabilities-and-space-diplomacy/. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

34 | China National Space Administration 国家航天局 (2015). “2015年10月29日《国家民用空间基础设施中长期发展规划(2015-2025年)》正式发布” (On October 29, 2015, the "National Civil Space Infrastructure Medium and Long-Term Development Plan (2015-2025)” was officially released). October 29. https://web.archive.org/web/20250925010531/https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758968/n6758972/c6797602/content.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025; State Council 国务院 (2014). “国务院关于创新重点领域投融资机制鼓励社会投资的指导意见” (The State Council's Guiding Opinions on Innovating Investment and Financing Mechanisms in Key Areas and Encouraging Social Investment). https://web.archive.org/web/20250901173805/https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2014/content_2786819.htm. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

35 | FuturePhecda 未来天玑 (2025). “全球及中国卫星行业:发展概况、产业链关键环节与未来转型方向” (Global and China’s Satellite Industry: Development Overview, Key Segments of the Industrial Chain, and Future Directions). September, 26. https://web.archive.org/web/20260115093336/https://www.futurephecda.com/news/19737. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

36 | Reuters (2019). “China to announce rules soon to regulate commercial rocket industry.” April 23. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-space-regulations/china-to-announce-rules-soon-to-regulate-commercial-rocket-industry-idUSKCN1RZ0UN. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Xinhua (2025). “China's commercial space sector strives to reach new heights.” June 20. https://web.archive.org/web/20260115094220/https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202506/1336571.shtml?utm_source=ts2.tech. Accessed: 28.10.2025; State Council (2025). “China's space authority sets up new department to oversee commercial space sector.” November 30. https://web.archive.org/web/20260115095243/https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202511/30/content_WS692b9763c6d00ca5f9a07da0.html. Accessed: 14.01.2026; State Council (2025). “China's space authority sets up new department to oversee commercial space sector.” November 30. https://web.archive.org/web/20260115095243/https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202511/30/content_WS692b9763c6d00ca5f9a07da0.html. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

37 | State Council (2025). “China's space agency unveils plan to boost commercial growth, international cooperation.” November 26. https://archive.ph/vl2xm. Accessed: 14.01.2026; China National Space Administration 国家航天局 (2025). “关于印发《国家航天局推进商业航天高质量安全发展行动计划(2025—2027年)》的通知” (Notice on Issuing the "Action Plan of China National Space Administration for Promoting High-Quality and Safe Development of Commercial Spaceflight (2025-2027)”). November 25. https://web.archive.org/web/20251204001357/https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758823/n6758839/c10719382/content.html. Accessed: 14.01.2025; MIIT 工信部 (2025). “工业和信息化部关于优化业务准入促进卫星通信产业发展的指导意见” (Guiding Opinions of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology on Optimizing Business Access to Promote the Development of the Satellite Communications Industry.) August, 27. https://archive.ph/9u2sq. Accessed: 28.10.2025; STCN 每日经济新闻 (2024). “《国家民用空间基础设施中长期发展规划(2026-2035)》正在编制” (The National Medium- and Long-Term Development Plan for Civil Space Infrastructure (2026–2035) is under development). November 11. https://web.archive.org/web/20241111071550/https://stcn.com/article/detail/1407521.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

38 | Space Mapper 太空地图 (2025). “Qianfan.” https://archive.ph/HI9kc. Accessed: 14.01.2026; CWW (2025). “垣信卫星13.36亿元招标,民营火箭将成“核心玩家”?” (Yuanxin Satellite's 1.336 billion-yuan tender: Will private rocket companies become "core players" ?) July 28. https://archive.ph/9wKCn. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

39 | In this report we spell out the original Chinese-language name of the main space companies we mention unless their international name is widely known outside China.

40 | Space Mapper 太空地图 (2025). “Guowang.” https://archive.ph/QMgk8. Accessed: 14.01.2026; IT Times IT时报 (2025). “独家:我国卫星互联网牌照发放倒计时,追赶马斯克星链” (Exclusive: China's Satellite Internet License Issuance Countdown Begins, Racing to Catch Up with Musk's Starlink). August 25. https://archive.ph/dw3vU. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

41 | ST Daily 中国科技网 (2025). “长征十二号火箭成功发射卫星互联网低轨卫星” (Long March 12 Rocket Successfully Launches Satellite Internet Low-Earth Orbit Satellites.) August 4. https://www.stdaily.com/web/gdxw/2025-08/04/content_380284.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

42 | State Council (2024). “China's new mega-constellation marks milestone in satellite internet.” August 9. https://web.archive.org/web/20241216132922/https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202408/09/content_WS66b55ad9c6d0868f4e8e9cf8.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Geely (2024). “Geely Future Mobility Satellite Constellation Nears Halfway Mark With Most Recent Global Service Launch.” September 6. https://web.archive.org/web/20251111080431/https://zgh.com/media-center/news/2024-09-06/?lang=en. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

43 | Space Mapper 太空地图 (2025). “Tianqi.” https://archive.ph/SkJxo. Accessed: 14.01.2026; Wang, Huabing 王华炳(2025). “基础化工周报:关注商业航天相关化工材料投资机遇” (Weekly Report: Focusing on Investment Opportunities in Chemical Materials Related to Commercial Aerospace). State Investment Securities via Sina. December 21. https://web.archive.org/web/20260115111322/https://stock.finance.sina.com.cn/stock/view/paper.php?symbol=sh000001&reportid=819638610124. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

44 | Curcio, Blaine (2025). “Chinese Space Financing Goes Mainstream.” China Space Monitor. October 20. https://chinaspacemonitor.substack.com/p/chinese-space-financing-goes-mainstream. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

45 | ITjuzi IT橘子. https://www.itjuzi.com/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

46 | ITjuzi IT橘子. https://www.itjuzi.com/. Accessed: 11.11.2025. Similar findings have been reported by the Space Ambition Research Center (2025). “China: Private Space Ecosystem of the Rising Superpower.” https://spaceambition.substack.com/p/china-private-space-ecosystem-of. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

47 | Ibid.

48 | Shijia, Ouyang, et al. (2025). “Fresh measures set to help create new growth drivers.” China Daily. March 7. https://web.archive.org/web/20250403233115/https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202503/07/WS67c9d1a4a310c240449d9282.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

49 | Shanghai Observer 上观新闻 (2025). “上海银行助跑“中国版SpaceX” 打造商业航天新生态” (Shanghai Bank Propels “China's SpaceX” to Build New Commercial Space Ecosystem). February 25. https://archive.ph/0GXYc. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Zheshang Bank浙商银行 (2025). “浙商银行助力中国商业航天追赶Space X!” (Zhejiang Commercial Bank Empowers China's Commercial Space Industry to Catch Up with SpaceX!) Weixin. March 5. https://archive.ph/wAgrI. Accessed:11.11.2025.

50 | Hainan International Commercial Aerospace Launch Co. 海南国际商业航天发射有限公司 (2025). “风云星闻|海南商业航天发射场二期项目今日开工” (Phase II of Hainan Commercial Space Launch Site Project Commences Construction Today). Weixin. January 25. https://archive.ph/z0W2G. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

51 | Sohu 搜狐 (2025). “两会·新质观察团|商业航天“造星”拼出千亿产业集” (Commercial Space Industry's “Star-Making” Efforts Forge a Hundred-Billion-Yuan Industrial Cluster). January 16. https://archive.ph/VBzEM. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

52 | Xu, Xiaofei and Frank Chen (2025). “Shanghai launches plan to lead development of China’s commercial space sector.” SCMP. April 28. https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3307880/shanghai-launches-plan-lead-development-chinas-commercial-space-sector. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

53 | 21st Century Business Herald 21世纪经济报道 (2024). “上海卫星企业获67亿元A轮融资:行业利好政策频出,盈利预期仍不乐观” (Shanghai-based satellite company secures 6.7 billion yuan in Series A funding: Despite frequent favourable industry policies, profit expectations remain pessimistic). February 2. https://archive.ph/6z6Ye. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

54 | ITjuzi IT橘子. https://www.itjuzi.com/. Accessed: 11.11.2025; STCN 每日经济新闻 (2025). “头部火箭公司星际荣耀再获7亿融资,此前披露IPO辅导工作进展”( Leading rocket company iSpace has secured another 700 million yuan in funding, following its previous disclosure of progress in IPO preparation). September 19. https://archive.ph/PMsUK. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

55 | Yicai 第一财经 (2025). “25天9次发射! “中国版星链”冲刺期有烦恼” (25 days, 9 launches! China’s Starlink equivalent faces challenges during its sprint phase). August 22. https://archive.ph/DPk4U. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

56 | Ibid; Guosen Securities 国信通信 (2025) “国信通信·卫星互联网专题四. 民营火箭亟待突破,手机直连与激光通信未来可期” (Guosen Communications · Satellite internet special topic 4: Private rockets urgently need breakthroughs; Direct-to-Cell and laser communications show great future promise). July 14. https://web.archive.org/web/20250826134514/https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202507141708784950_1.pdf?1752515352000.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025; STCN 每日经济新闻 (2023). “那个烧钱炸火箭的Space X,终于赚钱了” (SpaceX, the company that burned through money to blow up rockets, has finally made a profit). https://archive.ph/XoTrl. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

57 | Beijing Government 北京政府 (2025). “多款可重复使用火箭2025年将首飞北京打开万亿级低轨经济“太空入口”” (Several reusable rockets are scheduled for their maiden flights in 2025, opening a “space gateway” to a trillion-yuan-level low-Earth orbit economy for Beijing). June,19. https://archive.ph/xv1lY. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Mingyang, Tao. Global Times (2025) “China’s private space firm Galactic Energy completes reusable rocket test for forming satellite constellations.” https://archive.ph/b46su. Accessed: 11.11.2025; JF Daily 上观新闻 (2025). “在可重复使用火箭探索之路上,朱雀三号和长征十二号甲都值得点赞” (Both the Zhuque-3 and Long March 12A rockets deserve praise on the path of exploring reusable rockets). https://archive.ph/7zXSg. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

58 | LandSpace (2023). “China launches first globally successful orbital mission for methane-fueled rocket.” https://web.archive.org/web/20250815120521/https://www.landspace.com/en/news-detail.html?itemid=15. Accessed: 28.10.2025; China National Space Administration 国家航天局 (2025). “朱雀三号重复使用运载火箭发射入轨” (The Zhuque-3 reusable launch vehicle was launched into orbit). https://web.archive.org/web/20251209135528/https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758823/n6758838/c10720622/content.html. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

59 | Shenzhen Business Daily 深圳商报 (2019). “中国商业火箭企业已达49家 专家:量子卫星相关技术走在世界前列” (China now has 49 commercial rocket companies; experts say China's quantum satellite technology is among the world's leading). November 19. https://archive.ph/52X4T#selection-285.0-285.31. Accessed: 14.01.2026; Zhihu 知乎 (2025). “2025上半年,我国新增3家商业火箭公司” (In the first half of 2025, my country will add 3 new commercial rocket companies). July 15. zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/1926607327424939632. Accessed: 14.01.2026.

60 | China Great Wall Industry Corporation 中国长城工业集团有限公司. https://cn.cgwic.com/About/index.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

61 | U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2011). “2 Chinese nationals pleaded guilty to illegally attempting to export radiation-hardened microchips to the PRC.” May 31. https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/2-chinese-nationals-pleaded-guilty-illegally-attempting-export-radiation-hardened. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

62 | Yiwei, Wang (2019). “A State Scientist’s Views on China’s Microchip Industry.” Sixth Tone. February 8. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1003539. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

63 | EE World (2024). “中国版“星链”来袭,什么芯片“上天”了?” (The Chinese version of "Starlink" is coming, but what chips have been put into space?). August 8. https://archive.ph/M532k. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Futurephecda 未来天玑 (2025). “浅析中国商业航天元器件技术突破与生态重构” (A Brief Analysis of Technological Breakthroughs and Ecosystem Restructuring in China's Commercial Space Components Industry). June 26. https://web.archive.org/web/20250911113706/https:/www.futurephecda.com/news/13144. Accessed: 11.11.2025; STCN 证券时报网 (2024). “专访国科环宇董事长张善从:构建有竞争力的商业航天产业链,需关注底层基础创新与硬核研发” (Exclusive Interview with Zhang Shanzhong, Chairman of Guoke Huanyu: Building a Competitive Commercial Space Industry Chain Requires Focus on Foundational Innovation and Core R&D). December,12. https://web.archive.org/web/20241213013213/http:/www.stcn.com/article/detail/1449628.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025

64 | Semiconductor Industry 半导体产业纵横 (2022). “国产芯片“上天记”” (The Journey of Domestic Chips to Space). Retrieved via NetEase. August 23. https://web.archive.org/web/20250911120954/https:/www.163.com/dy/article/HFFKN8DQ0552OH9Y.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Zhihu 知乎 (2022). “自主可控!“神十四”用上国产宇航级CPU、FPGA” (Self-reliant and controllable! Shenzhou-14 employs domestically produced aerospace-grade CPUs and FPGAs.) June 6. https://archive.ph/wlPNf. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

65 | CAS 中国科学院 (2025). “抗辐照器件技术重点实验室-部门概况” (Key Laboratory of Radiation-Hardened Device Technology- Department Overview). https://archive.is/oiDXA. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

66 | CAS 中国科学院 (2025). “中国首款高压抗辐射碳化硅功率器件研制成功 通过太空验证” (China's First High-Voltage Radiation-Resistant Silicon Carbide Power Device Successfully Developed and Space-Tested). January 21. https://archive.ph/WHkFQ. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

67 | China High-Tech Industrialization Association中国高科技产业化研究会. “航天772所推出高可靠高安全亿门级宇航用FPGA” (Aerospace Institute 772 Unveils High-Reliability, High-Security Billion-Gate-Level Space-Grade FPGA). https://web.archive.org/web/20250911140242/https:/www.chia-spec.org/nd.jsp?id=85. Accessed: 11.11.2025; EET China 电子工程世界 (2024). “中国版“星链”来袭,什么芯片“上天”了?” (China's Starlink Alternative Arrives: Which Chips Made It to Space?) August 8. https://web.archive.org/web/20250911123222/https:/www.eet-china.com/mp/a337519.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

68 | EETOP 易特创芯 (2019). “我国星载、机载计算机和核心器件相关公司及水平” (China's Companies and Capabilities in Satellite-borne and Airborne Computers and Core Components.) April 6. https://web.archive.org/web/20220810201023/https:/www.eetop.cn/semi/6943515.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Zhihu 知乎 (2024). “24家太空芯片主要玩家及产品” (24 Key Players in Space Semiconductor and Their Products). December 10. https://archive.ph/4M2Fz. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

69 | Global Times (2025). “Chinese scientists achieve breakthrough in low-Earth orbit satellites.” August 25. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202508/1341694.shtml. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

70 | Arcesati, Rebecca (2025). “Laser Starcom (极光星通): A breakthrough for optical intersatellite communications?” MERICS. October 2. https://merics.org/en/comment/laser-starcom-jiguangxingtong-breakthrough-optical-intersatellite-communications. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

71 | Xinhua (2025) “Chinese-led team achieves world's first 10,000-km quantum-secured communication.” March 21. https://web.archive.org/web/20250321192701/http://english.scio.gov.cn/chinavoices/2025-03/21/content_117778711.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

72 | South China Morning Post (2025). “China’s new Dawn: Pan Jianwei reveals high-orbit quantum satellite for global network.” June 26. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3315963/new-dawn-pan-jianwei-reveals-high-orbit-quantum-satellite-global-network. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Er, Donglie尔东烈(2025). “曙光计划揭幕:中国高轨量子卫星瞄准全球通信” (Dawn Project Unveiled: China's High-Orbit Quantum Satellite Targets Global Communications). Baidu. June 27. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1836015846564198399&wfr=spider&for=pc. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

73 | Huawei (2022). “Very-Low-Earth-Orbit Satellite Networks for 6G.” https://www.huawei.com/en/huaweitech/future-technologies/very-low-earth-orbit-satellite-networks-6g. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

74 | DigiTimes (2024). “Huawei and Unisoc targeting 6G with new strategies.” October 24. https://www.digitimes.com/news/a20241023PD226/6g-huawei-unisoc-technology-communications.html. Accessed: 28.10.2025.

75 | Olcott, Eleanor (2022). “The corporate feud over satellites that pitted the west against China” June 22. https://www.ft.com/content/f1f342ab-d931-44ca-bf0d-f7762db76982. Accessed: 28.10.2025; Mc Nicholas, Aaron (2023). “China, Europe and the U.S. Struggle for Satellite Supremacy.” The Wire China. October 8. https://www.thewirechina.com/2023/10/08/china-europe-and-the-u-s-struggle-for-satellite-supremacy-kleo-connect/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

76 | KLEO. https://kleo-connect.com/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

77 | Olcott, Eleanor (2022). “The corporate feud over satellites that pitted the west against China.” Financial Times. June 22. https://www.ft.com/content/f1f342ab-d931-44ca-bf0d-f7762db76982. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

78 | Rainbow, Jason (2024). “Rivada brushes off regulatory setback for proposed broadband constellation.” Space News. December,13. https://spacenews.com/rivada-brushes-off-regulatory-setback-for-proposed-broadband-constellation/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

79 | ThurstMe (2020). “ThrustMe and Spacety announce the launch of a satellite carrying the world’s first iodine electric propulsion system.” November 6. https://en.spacety.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Thrust-Me-Launch-PR-v6-EN.pdf; https://www.thrustme.fr/our-missions. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

80 | Rafalskyi, Dmytro. Martínez, Javier Martínez. Habl, Lui. Rossi, Elena (2021). “In-orbit demonstration of an iodine electric propulsion system.” Nature 599(7885):411-415. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356290781_In-orbit_demonstration_of_an_iodine_electric_propulsion_system; NASA (2024). “4.0 In-Space Propulsion.” March 17. https://www.nasa.gov/smallsat-institute/sst-soa/in-space_propulsion/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

81 | ESA (2021). “Iodine thruster could slow space junk accumulation.” January 22. https://www.esa.int/Applications/Connectivity_and_Secure_Communications/Iodine_thruster_could_slow_space_junk_accumulation. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

82 | Krauss, Luka (2023). “Space company investigated over alleged Russian ties.” EURACTIV. March 15. https://www.euractiv.com/short_news/space-company-investigated-over-alleged-russian-ties/. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Nardelli, Alberto et al. (2023). “US Urges EU to Sanction Chinese Satellite Firm Over Russia Aid.” Bloomberg. March 29. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-29/us-urges-eu-to-sanction-chinese-satellite-firm-over-russia-aid. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Agarwal, Kabir (2024). “Luxembourg unit of sanctioned space firm files for bankruptcy.” Luxembourg Times. October 14. https://www.luxtimes.lu/luxembourg/luxembourg-unit-of-sanctioned-space-firm-files-for-bankruptcy/22950888.html. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Council of the European Union (2024). “COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) 2024/1745 of 24 June 2024 amending Regulation (EU) No 833/2014 concerning restrictive measures in view of Russia’s actions destabilizing the situation in Ukraine.” Official Journal of the European Union. June 24. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401745. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

83 | SPACETY 天仪研究院 (2022). “天仪研究院率先实现国产商业SAR卫星批产组网” (Tianyi Research Institute Leads the Way in Achieving Mass Production and Network Deployment of Domestic Commercial SAR Satellites). Zhihu. February 27. https://archive.ph/Tfxv2. Accessed: 11.11.2025; Hundman, Eric (2025).“China’s Air Defense Radar Industrial Base.” China Aerospace Studies Institute. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Research/Infrastructure/2025-03-10%20Air%20Defense%20Radars.pdf?ver=n23Kh46_R--EG2y9MEQAPg%3D%3D. Accessed: 11.11.2025

84 | Titcomb, James (2023). ”MI5 investigated attempted Chinese takeover of British satellite company.” Telegraph. July 30. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2023/07/30/mi5-investigated-chinese-takeover-attempt-oneweb-satellite/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.; UK Parliament (2023). “Eutelsat. Question for Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.” October 13. https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-10-13/201047/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

85 | Feigl, Maximilian (2020). “Mynaric withdraws from China and appoints new US head.” Munich Startup. August 22. https://www.munich-startup.de/63600/mynaric-zieht-sich-aus-china-zurueck-und-ernennt-neue-us-chefin/. Accessed: 01.23.2026; Nienaber, Michael (2020). “Germany blocks Chinese takeover of satellite firm on security concerns – document.” Reuters. December 8. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/germany-blocks-chinese-takeover-satellite-firm-security-concerns-document-2020-12-08/. Accessed: 01.23.2026.

86 | Die Bundesregierung (2025). “Space Safety and Security Strategy.” https://www.bmvg.de/resource/blob/6042580/128dbebd8cce8d7b8e61eb680edf91ad/weltraumsicherheitsstrategie-2025-en-data.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

87 | European Commission (2022). “COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS - Roadmap on critical technologies for security and defence.” February 15. https://www.kowi.de/Portaldata/2/Resources/fp/2022-com-Security-Defence.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

88 | European Commission (2025). “White Paper for European Defence – Readiness 2030.” March 6. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6d5db69-e0ab-4bec-9dc0-3867b4373019_en?filename=White%20paper%20for%20European%20defence%20%E2%80%93%20Readiness%202030.pdf. Accessed: 11.11.2025; U.S. Department of War (2024). “Joint Statement From the Combined Space Operations Initiative.” September 26. https://www.war.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3918135/joint-statement-from-the-combined-space-operations-initiative/. Accessed: 11.11.2025.

Ackowledgements

The authors would like to thank MERICS student assistants Mauricio Selig and Ru-Tung Sun for their research support.