Expert debate on: What does it really mean for Europe to ‘de-risk’ its relationship with China?

At the core of many EU Commission and member states’ recent discussions of China is the concept of “de-risking.” Distinct from “decoupling,” the concept focuses on mitigating risks and limiting strategic dependencies in Europe’s relationship with China. They would achieve this using the EU’s economic defenses more effectively and engaging in open and frank dialogue, while remaining open to targeted cooperation and economic ties that are considered “un-risky.”

On July 13, Berlin unveiled its long-awaited Strategy on China, which states that de-risking is “urgently needed.” Germany is China’s largest trading partner in Europe, it receives far more Chinese investment than any other EU member state, and the German automotive industry alone constituted more than 40 percent of the EU’s foreign direct investment into China in 2021. These deep economic ties mean that Berlin’s approach to Beijing has an outsized influence on those of its neighbors. The Strategy on China may best be described as a position paper, rather than an exhaustive policy blueprint, but it nevertheless serves as an important reference point for Brussels and European capitals as they consider recalibrating their approach towards Beijing.

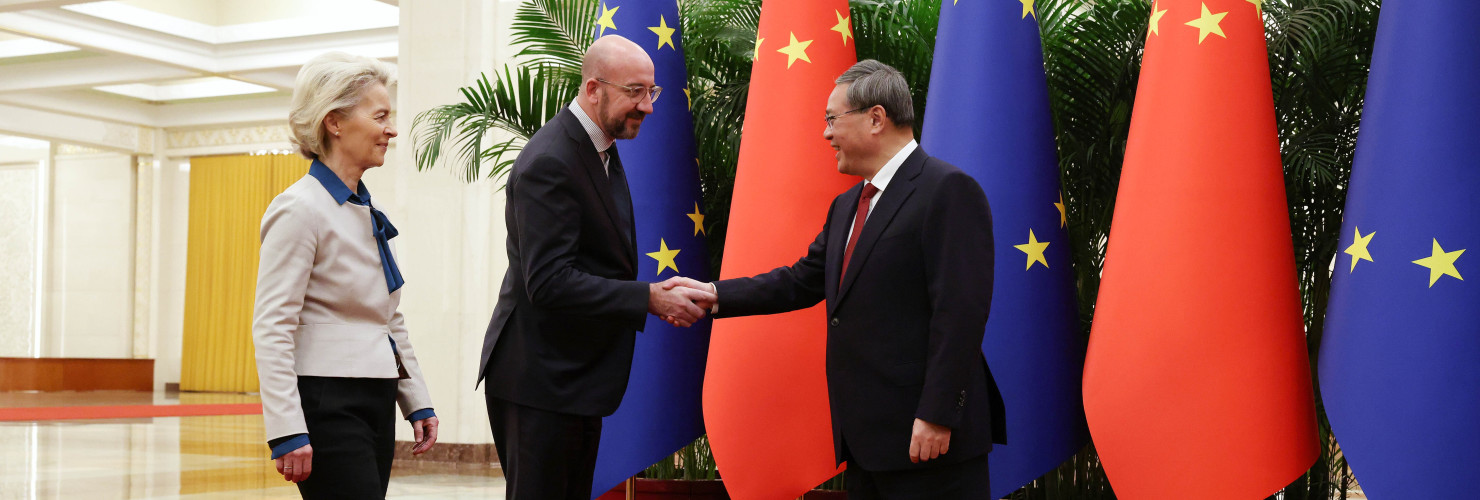

As introduced by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in March, “de-risking” includes not just economic but also diplomatic and geopolitical considerations. Yet in a missive from late June, the European Council - which, together with the European Commission, forms the executive arm of the European Union - only broached “de-risking” in economic security terms. In October, the Commission launched a risk assessment of, initially, four critical sectors (semiconductors, AI, quantum computing, and biotech) relevant in the context of the EU’s exports to China. The number of sectors assessed would likely have been higher had it not been for reluctance among some of the EU member states.

Discrepancies between the Commission and member states underscore the ongoing debate about what it means to “de-risk.” Even as many EU member states broadly agree on the challenges posed by contemporary EU-China relations, their post-pandemic approaches to re-engaging with Beijing have taken very different forms. What is the state of the de-risking China debate following the release of Germany’s China Strategy, and what will de-risking ultimately mean in practice?

In this round of MERICS’ EU-China opinion pool, MERICS Analyst Grzegorz Stec asked several experts:

What does it really mean for Europe to ‘de-risk’ its relationship with China?

This debate was compiled in collaboration with ChinaFile.

Una Bērziņa-Čerenkova

Head of the Asia program at the Latvian Institute of International Affairs,

European China Policy Fellow at MERICS

Even if they agree with the basic idea of de-risking, EU member states differ greatly in how they envision its scale and scope. While Western Europe is struggling with the implications economic disengagement from China might bring, for northeastern member states — including the Baltic states, as well as other nations in Central and Eastern Europe — it is clear that economically painful decisions must be taken to outweigh the geopolitical risks of overreliance on China.

Unlike in larger member states like Germany, the debate on the economic aspects of de-risking in these countries is moot because they have minimal economic entanglement with China. China’s heightened interest in the region over the past decade has not translated into substantial economic benefits, meaning these countries have not become overly dependent on China. As Andreea Brinza highlights, citing data from MERICS, a mere 38 percent of the €147.2 billion invested by China in the EU between 2000 and 2022 went to countries outside the Western European nations of Germany, France, the Netherlands, Italy, and Finland.

Geopolitics, however, is at the forefront of the de-risking debate in northeastern EU member states due to the decades of Soviet occupation (the Baltics) and Soviet-imposed control (Poland). Ukraine’s fight to preserve its sovereignty and align itself with European and Western values echoes the recent history of these northeastern European nations, who similarly reclaimed their statehood and are cognizant of their geopolitical vulnerability. China’s stance following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has not resonated well with these member states. Far from opposing Russia, Xi Jinping showcases Vladimir Putin as a top guest at important events, including the Third Belt and Road Forum that recently concluded in Beijing. For northeastern Europeans, these are signals that China’s geopolitical vision is not one that makes the world safe for small EU members.

Thus, when it comes to the European debate on de-risking, smaller EU members with little to lose are willing to go further than their larger Western neighbors.

Jakub Jakóbowski

Deputy Director at Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW)

“De-risking” is certainly a positive policy innovation in EU-China policy. It is self-explanatory, implies a selective approach, and assumes the global network of capital and trade will be maintained — but with more strategic guidelines. At last, the EU is no longer debating the “decoupling is impossible” strawman, a long-standing excuse to maintain a status quo in which China leveraged its economic relationship with Europe to neutralize the EU in global politics and get a competitive edge over Europe’s industry.

However, the task of filling the “de-risking” concept with tangible, strategically meaningful content will require clear political guidance. Assigning the de-risking task to private business — a strategy selected by Germany, for instance — is a fundamentally wrong solution. It is precisely the short-term attitude aimed at maximizing quarterly profits that got us into serious dependencies in the first place. Even if Beijing’s policies towards the EU as a whole are ham-handed, it often quite skillfully uses a mix of incentives and thinly veiled coercion to encourage Europe’s big industrial players to lobby the EU on its behalf. Increasingly polarized internal politics in Europe mean that the EU will find it difficult to reign in European industrial players’ vested interests. However, the geopolitical awakening of the EU following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gives hope that an EU-wide, top-down political consensus could bring about change.

Even so, calling on EU businesses to fundamentally reshuffle global supply chains without any incentives or support could harm European competitiveness. European car manufacturers are flocking to China—“re-risking,” rather than “de-risking” the relationship—because the People’s Republic of China offers a robust technological ecosystem, regulatory incentives for electric vehicles, and fine-tuned upstream value chains. The EU’s calls for de-risking, then, should be coupled with a robust EU-wide industrial policy targeting both Europe’s industrial core as well as a long value chain that includes EU’s neighbors and select partners in the Global South.

De-risking should transcend the EU’s compartmentalized policy initiatives. It will be possible to achieve only if it is firmly linked with the EU’s industrial policy initiatives, such as the Global Gateway and the Green Deal. In order to achieve this, Europe needs not only strong leadership and consensus, but also a radical policy push towards an EU-wide industrial policy that follows China’s and the U.S.’s footsteps.

Alicia Garcia-Herrero

Chief economist for the Asia pacific at NATIXIS and Senior Fellow at Bruegel

De-risking has become a buzzword, but one with quite different meanings. While the U.S. understanding focuses on national security, the EU takes a more economic approach, aiming to reduce excessive dependence on China for the sourcing of critical raw materials and manufactured goods. EU member states hold different views regarding the risks of dependence on China, ranging from Hungary’s outright rejection of the need to de-risk at the Belt and Road Summit to Lithuania’s calls for fast action to reduce the chance China will retaliate. Germany’s China strategy sits in between these two extremes.

Two large, unexpected shocks explain the EU’s shift from engagement to de-risking. The first is the COVID-19 pandemic, which made painfully obvious how much the EU depended on China for goods like masks, respirators, etc. The second shock was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in which the overreliance on Russian gas suddenly turned out to be very costly.

The EU also depends on China for its decarbonization, through massive imports of solar panels, electric batteries, and wind turbines. Even if the EU were to decide to de-risk quickly by importing from another economy, there is simply not enough capacity anywhere to meet the demand for green tech. The U.S.’ response to its reliance on China has boiled down to reshoring the production of renewables through subsidies, which is also diverting green tech resources away from the EU as they are attracted by U.S. subsidies. This has put a lot of pressure on the commission to create policies that reduce the EU’s reliance on China for our decarbonization. However, the tools available so far, including the Critical Raw Material Act and the Net Zero Industrial Act, will not substantially reduce the many critical dependencies along the supply chain, from extraction and refining to manufacturing and even green tech innovation.

All in all, Europe is fully aware of its excessive dependence on China, but does not have a solution to alleviate this dependence. The EU cannot follow the U.S. path as it lacks the fiscal space to subsidize a reindustrialization process. Europe’s search for diversification of critical raw materials and even manufacturing is commendable, but for EU member states to significantly decarbonize, more concrete actions are needed to diversify green tech sourcing.

Francesca Ghiretti

Former Analyst, MERICS

In broaching the idea of de-risking, Brussels has triggered a very important process, and it has done so in the ambitious fashion that has largely characterized Ursula von der Leyen’s leadership of the European Commission. Like other ambitious Commission agenda items, de-risking—designed to increase EU resilience—now faces uneven and difficult implementation. Two key factors underlie this challenge: the capaciousness of the term “de-risking” itself and the EU’s long-standing coordination issues.

Adopting a flexible term has its advantages: Since EU leaders starting using the term in early 2023, the phrase “de-risking” has become a mainstay of global conversation, including in the U.S. However, expansive terminology also allows for wildly varying interpretations. In the EU, this has meant that “de-risking” has lost its diplomatic component and now only describes economic activity.

Yet, varying definitions of “de-risking” perhaps present a smaller challenge than the task of coordinating between EU member states that cannot, or will not, develop the capacity to enact it. For example, member states already struggle to efficiently implement investment screening and export controls—a long-standing cornerstone of EU economic security policies. The result? A high degree of incoherence within the EU that will only increase as de-risking policies proliferate, unless countries choose to structurally coordinate more and cede more responsibility to Brussels, when needed.

A key component of de-risking is risk assessment. The risk assessment process, however, will likely highlight even more challenges. First among them is data access: Brussels and other member states have, at best, uneven access to data needed to conduct risk assessment—if such data even exists in all cases. Second is methodology: Brussels and member states have not yet defined the core components of a de-risking assessment. Differences in data or methodology could lead to inconsistent results across the EU. Finally, Brussels must find a way to ensure member states carry out risk assessment in a timely fashion and share information afterwards. As is almost always the case for ambitious policy proposals, the success of de-risking will be predominantly determined by its implementation.

Thomas König

China Director at Deutsche Industrie- und Handelskammer (DIHK)

Our debate on “de-risking” needs more honesty about and accountability for the current consequences of that fateful verbiage. On one side, there is mistrust: During recent research trips to China, high-level Chinese counterparts across a number of Chinese decision-making bodies told me that Germany’s “de-risking” ambitions were “just window-dressing for de-coupling.” On the other, there is bewilderment: Contacts at German companies have professed confusion about German policymakers’ vision for engagement with China. Some even tell me that, because their company happens to have a Chinese investor, they are losing official German and EU tenders due to the public perception that they “directly report to the Communist Party of China.”

What’s more, this uncertainty is not based on economic data. Our organization has decades’ worth of empirical data regarding the Sino-German economic relationship, and, over the past five decades, more than 5,000 German companies have contributed significantly to the “China success story.” German companies, in turn, have profited. Despite the challenges presented by COVID—and despite policymaker ambitions to reduce dependence on China for critical resources—German enterprises both large and small continue to depend on China as a key market and remain generally confident of its ongoing potential.

Thus far, German and European policymakers have failed to adequately outline any concrete goals of the China strategy. Nor have they appropriately prepared the business community for the fallout of “de-risking” or created appropriate incentives for the business community to follow the strategy’s vague designs. However, even if the debate surrounding the China strategy has been somewhat clumsy, I view “de-risking” as an important catalyst: because of the “de-risking” debate, the business community has conducted an open assessment of the long-term importance and viability of Sino-German business relations. So far, all signs point towards continued engagement with China—and we should take those signs seriously.

Even so, our organization will continue to raise awareness for the new supply chain law in mainland China and maintain both high-level and working-level Sino-German dialogues. Next year, the network of German chambers of commerce will offer a “Diversification Desk” to help German companies based in China explore potential markets for diversification.

We are just beginning to assess “de-risking,” an undoubtedly worthwhile endeavor. But let’s make sure we use the opportunities that come with it wisely and in a coordinated manner that includes all stakeholders.

This MERICS EU-China Opinion Pool is part of the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.