Reverse Deng? For professionals only

The tables have turned. Western governments are now contemplating extracting industry-leading know-how from Chinese investment in order to help modernize their domestic manufacturing, argues Yanmei Xie.

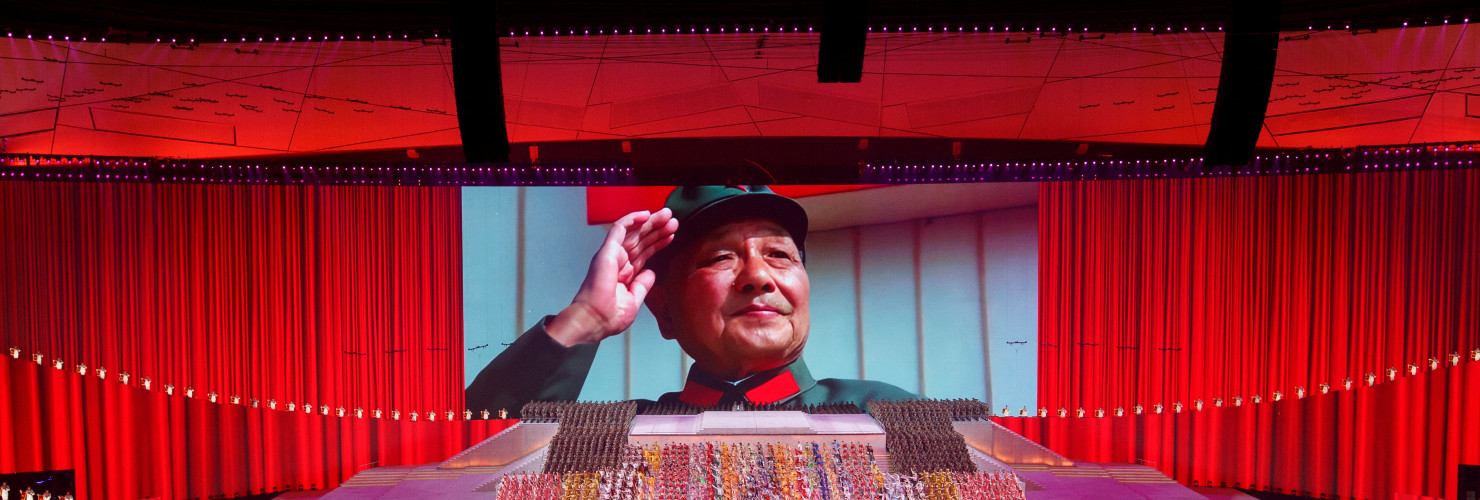

Call it the “Reverse Deng,” in homage to Deng Xiaoping, the chief architect of China’s reform and economic opening up in the 1980s. Deng boldly invited foreign companies in to accelerate the country’s growth and development. That strategic brilliance is evident in the global success of Chinese companies, most notably in EVs, batteries, and clean-energy equipment.

Western governments are considering adapting Deng Xiaoping's playbook

Western governments are now considering adapting his playbook. The European Union, already a major destination for Chinese EV investment, is preparing regulations that would require technology and skills transfer as entry conditions. The US remains mostly closed to such investment, but commentators, notably Thomas Friedman, have been calling for similarly conditioned partnerships. It’s a potentially smart move for Western countries — so long as they understand exactly what it entails. It is a multi-faceted, multi-decade, infant-industry strategy that combines clever utilization of foreign capital and expertise with shrewd protectionism around would-be indigenous champions.

When China first opened its doors 40 years back, it mostly confined foreign factories to a fewcoastal special economic zones to produce mainly for export.

Growing up in China, I heard adults lament that “Made in China” products sold abroad were of far better quality than those found at home. Unscrupulous capitalists got blamed for exploiting less-discerning Chinese consumers.

In reality, this was partly the result of deliberate policy. Segregating foreign firms from the domestic market helped reassure conservative leaders wary of capitalist infiltration. More importantly, this dual system brought in advanced technology and hard currency, while allowing domestic industries to emulate foreign competitors without being crushed by them.

China did not invent this approach. It learned it from other successful East Asian developmental economies such as South Korea and Taiwan. South Korean developmental economist Ha-Joon Chang wrote that his country similarly contained foreign investment initially because otherwise it would “destroy existing national firms that could have ‘grown up’ into successful operations without this premature exposure to competition.”

Over time, China loosened restrictions, but continued to manage a detailed and evolving list of industries that were categorized as prohibited, restricted or encouraged for foreign investment, based on each sector’s strategic importance and competitive readiness. Until 2016, major foreign investment projects still required case-by-case approval. Local and central officials often cajoled and pressured foreign companies to form joint ventures, use local suppliers, and share technology with would-be Chinese national champions. The government also supported home-grown companies through procurement, financing and subsidies, in some cases tilting the field decisively in their favor.

Take the electric vehicle industry. In the mid-2010s, the Chinese government went all in to promote mass production and adoption of EVs. It rolled out a “white list” of batteries in 2015: Only EVs using batteries on this list qualified for purchase subsidies, which peaked at USD 19,000 per car.

No foreign battery makers ever made the list, even though Japanese and Korean manufacturers were the industry leaders at that time. LG Chem had just opened a mega battery factory in Nanjing and Samsung SDI was planning to expand, both hoping to ride China’s EV boom. Instead, their factories wound up running at just 10 percent of their capacity after being excluded from Chinese consumer subsidies. LG Chem sold its Nanjing plant to Chinese carmaker Geely in 2017. Samsung SDI downsized its battery business in China in 2022.

Foreign carmakers were also caught off guard. Many of them had partnered with Japanese or Korean battery makers and had to switch to Chinese suppliers in haste. Redesigning and testing EV models with new batteries set them a couple years behind their Chinese competitors.

Once China’s homegrown companies are mature enough, the government has been willing to let in foreign competition. Beijing allowed Tesla to open a wholly owned gigafactory in Shanghai, using Panasonic batteries, in 2018 and provided it with the full suite of government support. By then, of course, Chinese brands commanded 90 percent of the domestic EV market and had begun exporting.

Joint ventures are no magic wand

Advocates of a Western “Reverse Deng” frequently prescribe joint ventures with local firms as a way to get the most out of inviting Chinese companies in. But China’s own experience shows that JVs are no magic wand. The automotive industry was the first that China opened to foreign partnerships: American Motors Corporation (later taken over by Chrysler) teamed up with a Chinese carmaker in 1983.

There have been a dozen or more JVs formed since then, but none have produced an internationally recognizable Chinese gasoline-car brand. Western carmakers skillfully kept their core R&D at home. Their Chinese partners were mostly state-owned enterprises, hardly known for their adaptability or innovative zest. Perhaps most crucially, it has proven much easier for the junior JV partner — in this case the Chinese company — to profit from the technology and brand recognition of the incumbent than to do the hard work of learning and innovating.

Now it’s Western companies that are becoming the junior partners. The former chief executive of Stellantis, Carlos Tavares, engineered one such JV with Chinese EV maker Leapmotor in 2024. Later relieved of his post, he bluntly assessed that Leapmotor was out “to swallow us some day” and did not sound optimistic about Stellantis’s prospects.

Costs are one of the biggest differences between the Chinese joint venture experience under Deng and the situation for Western firms now. China effectively leveraged its low-cost advantage to attract foreign investment for technological upgrade. In industries that China now dominates, Western companies face the double whammy of lagging technologically and pricier inputs, particularly labor costs. Even if they acquire Chinese know-how through tech transfers or joint ventures, these firms could still struggle to compete. After all, a master chef who pays less for salaries, overheads and ingredients will still outcompete a novice cooking from the same recipe. To narrow the cost gap, Western governments should aggressively enforce local hiring and sourcing requirements as part of any deal.

A demanding, capable and charismatic industry leader — known as a “dragon head enterprise” in China for its ability to lift up an entire sector — can upgrade workforces, whip suppliers into shape and even create new, productive and innovative ecosystems.

Apple and Tesla never entered JVs with Chinese companies, nor did they formally transfer product designs to them. Nonetheless, both American companies helped transform Chinese manufacturing. Chinese officials combined enticements and pressure to ensure both produced and sourced locally. Of Apple’s 187 suppliers, 84 percent had production facilities in China in 2023. Apple provided advanced equipment to suppliers in China and trained their engineers on new manufacturing techniques. The result is a fiercely cost-effective and innovative electronics supply chain in China which has given rise to Apple’s rivals, such as Huawei, Vivo and Oppo.

Tesla by 2022 had localized over 95 percent of its supply chain for its Shanghai plant. It helped Chinese supplier LK Group develop the world’s largest die casting machines to make Tesla parts. Chinese EV makers quickly adopted this so-called “giga press,” which significantly reduced both cost and production time for key components. As the success of China’s strategic use of foreign investment is plain to see, Western countries should attempt to “reverse Deng,” but must absorb the infant-industry strategy in full. Hard as it may be to swallow, Western EV and battery industries are infants compared with Chinese giants. They need to learn from China’s industry leaders but would likely not survive immediate head-on competition with them. Successfully applying Deng’s playbook requires combining and constantly recalibrating emulation, protection and competition.

This article was originally published by The Wire China on November 23, 2025.