From talk to action: Europe’s relations with Beijing in the year ahead

2020 promises to be a critical year in Europe-China relations. Results of a MERICS expert survey, however, indicate that prospects for success look dim, unless European governments can translate last year’s shift in rhetoric into real changes in policy and approach.

Last year marked the end of naïveté on China in Brussels and other European capitals. In addition to labelling China a ‘systemic rival’, the European Commission’s strategic outlook of March 2019 acknowledged China’s rising role as a political and security actor and the implications this has for Europe. This awareness is reflected in the EU’s adoption of an investment screening mechanism and coordination work on 5G risk mitigation. Both will likely affect Chinese actors on the ground, like telecom equipment provider Huawei. Last year, President Ursula von der Leyen also promised to make her Commission ‘geopolitical’ and to better “define relations with an increasingly assertive China”.

All the while, Xi Jinping’s campaign to “tell China’s story right” has prompted Chinese ambassadors in Europe to voice blunt criticism of democratic institutions, targeting individuals and organisations in the media, parliaments, and civil society whose views diverge from Beijing’s official positions. European governments thus face an increasingly delicate balancing act, having to defend their political values against an assertive China while at the same time trying to safeguard potentially lucrative economic cooperation.

Beijing, on its part, has defined Europe as a priority on its diplomatic agenda and has appointed ambassador Wu Hongbo as its first special envoy on European affairs. The Chinese government has also promised to conclude an ambitious Comprehensive Agreement on Investent (CAI) with the EU by the end of the year. Germany would like it to be signed during its presidency of the Council of the EU at a summit in Leizpig in September, which will gather Xi and all 27 EU leaders around the table.

Will Europe and China be able to hail breakthroughs on their stated goals in the year ahead? And which new trends are going to define Sino-European relations going forward? A MERICS forecasting exercise surveyed the opinions of around 150 European China experts and practitioners from think tanks, government, industry and civil society. Their answers give us insights into what Europe should prepare for with regards to China in 2020.

Business as usual is no longer an option in times of systemic rivalry

According to the MERICS survey, political issues will most likely strain Sino-European ties in 2020, adding to long-standing economic issues. Beijing’s politically motivated retaliation against European governments and companies was ranked as the number one factor that might aggravate tensions. This came before restrictions on access to the Chinese market, followed by human rights violations.

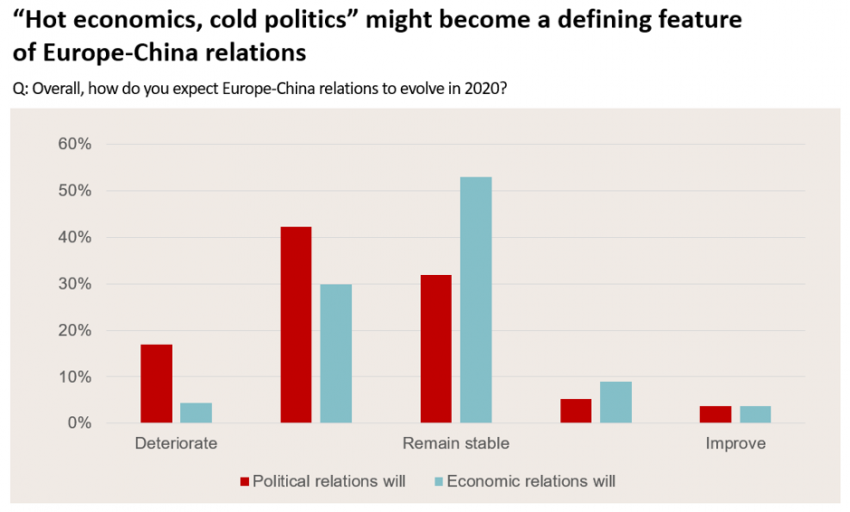

Interestingly, while the majority of experts surveyed expect political relations to worsen (17% said they will deteriorate, 42% believe they will deteriorate slightly), 53% of respondents forecast stable economic ties. Are Europeans naïve to think they can have both? The case of Sweden shows that they might be right. So far, a diplomatic row over China’s detention of Chinese-born Swedish bookseller Gui Minhai has not affected trade and investment ties. This has led Swedish experts to talk about “hot economics, cold politics” in bilateral relations. If survey respondents are right, this might become a defining trend in European countries’ relations with China more broadly.

For some countries, economic retaliation might not be an issue at all. When Prague’s city council decided to terminate its sister city agreement with Beijing over the “One China” pledge – replacing it with Taipei – there was not that much to lose in economic terms. China’s promised investment to the Czech Republic has largely failed to materialize, in spite of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) stipulating closer cooperation in the framework of the Belt and Road infrastructure initiative and regular high-level exchanges through the 17+1 format since 2012. Notably, Czech President Milos Zeman, who had been keen to forge closer ties with Beijing, will not attend the next summit between China and central and eastern European countries over this ‘investment let-down’.

The Czech case is indicative of another fact European countries are beginning to realize, that is, forging stronger political relations with Beijing is no short cut to business or other preferential treatment. Besides the Czech Republic, Italy is also beginning to feel the heat: the country signed an MoU on Belt and Road cooperation in March. But exports to China declined in 2019, highlighting the symbolic nature of the agreement. Additionally, Italian politicians were recently criticized by the Chinese embassy after holding a video conference with Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong, showing that MoU holders are not being spared Beijing’s criticism.

For states like Germany, whose economy is more dependent on the Chinese market, things might be trickier. In the current heated debate over whether to allow Huawei to build the country’s 5G network, Beijing has threatened Germany where it hurts: German car exports to China. Regardless of which of these scenarios European countries find themselves in, it is clear that a sustainable, long-term strategy toward China cannot be dominated by fear of retaliation or the appeal of China’s market potential.

It’s up to the Europeans to make 2020 China’s “year of Europe”

In his December speech at the European Policy Center in Brussels, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi insisted that “we are partners, not rivals”. There is no doubt that the EU and China must do their best to cooperate on global challenges, such as mitigating climate change and promoting peace and security. But how likely is it that China will carry through with its promise and pay more attention to Europe in 2020?

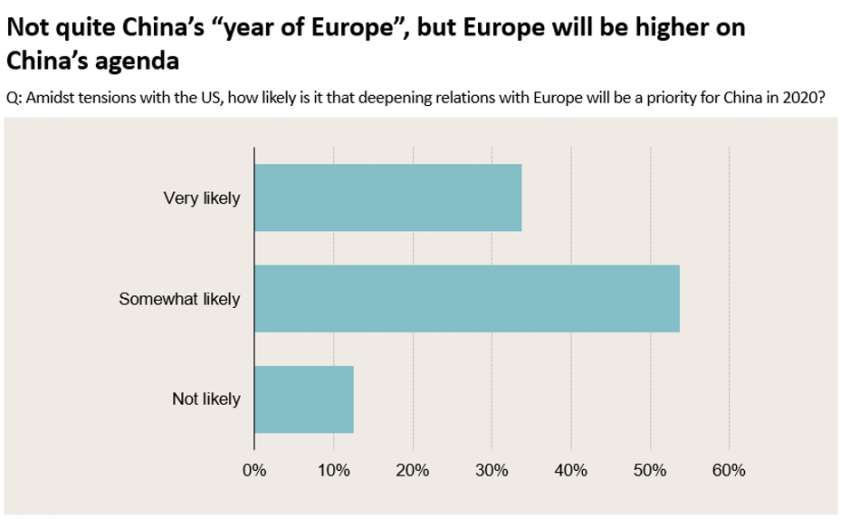

The large majority of experts surveyed by MERICS think that it is credible: 54% said it was somewhat likely and 34% said it was very likely that, against the backdrop of Sino-US competition, China will make deepening strategic relations with Europe a priority this year.

If China is serious about avoiding tensions getting in the way of cooperation, one might ask what Beijing is willing to do to make this possible. However, it does not look like the EU can hope for much from the Chinese side.

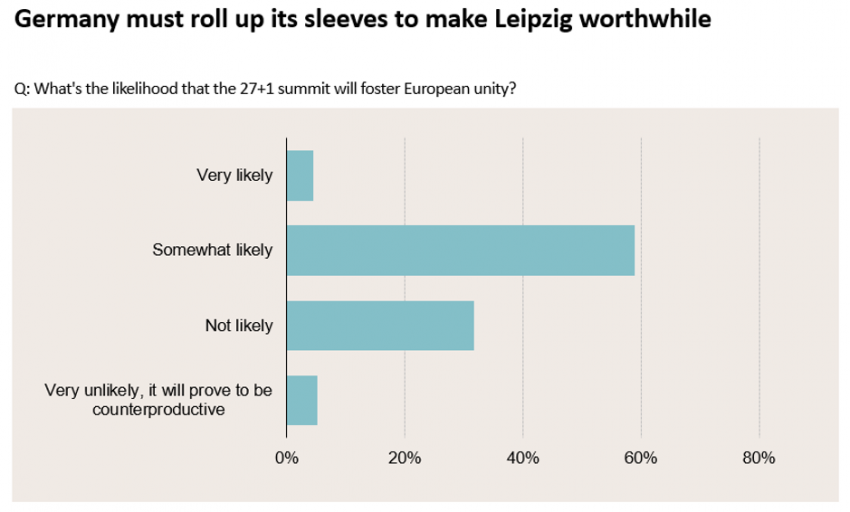

The signing of a first phase trade agreement between the US and China eases the pressure on Beijing to foster friendships in Europe. Beijing’s upgrading of the 17+1 gathering, with Xi Jinping taking over chairmanship from Li Keqiang, weakens German efforts to provide a counterweight to the contested format by hosting Xi and all EU member states leaders in Leipzig. Similarly, thus far unsatisfactory negotiations over the EU-China investment deal, high on the agenda for this summit, threatento undermine its outcomes. Prospects of breakthrough on stated goals are uncertain, and only 4.5% of experts who responded to the MERICS survey find it “very likely” that Leipzig will foster European unity, against a more substantial 32% who consider it unlikely.

It looks, therefore, like it might be up to the Europeans to make this China’s “year of Europe”. Governments across Europe will need to sharpen their policy responses and statements if they want to spur on the desired changes in China’s approach to their countries and ongoing negotiations.

Germany, on its part, needs to ensure that the process leading up to the Leipzig summit provides a platform for real intra-European working-level exchange and coordination. This is an opportunity to get up and running a common European approach to China. More broadly, Germany’s credibility as a driver of a common policy on China will also depend on its ability to decide strategically on the Huawei/5G issue, without letting itself be confined by short-term economic interests.

The debates over Huawei across Europe highlight the need to address the fault lines between short-term economic interests and long-term strategic considerations in member states’ China policies. The Netherlands has set an example of how to approach this by creating a task force to assess the impact of Chinese investments or contributions to 5G build-up on national security matters. In addition, an inter-ministerial task force on China has been created to pull in knowledge and link up issues across domains.

As for Brussels, in the MERICS expert survey investment in industrial competitiveness and innovation emerged as key to getting the EU-China relationship right, and took priority over human rights policy. However, an exclusive focus on internal issues would be short-sighted if the EU is to “learn to use the language of power”, as EU High Representative Josep Borrell recently stated. Besides, the systemic differences, normative and value dimensions of the EU’s relationship with China will need to be factored into the overall geopolitical approach that von der Leyen has committed to. The December proposal for an EU sanctions regime targeting human rights violators is a step in the right direction.

The EU has traditionally been more comfortable and suited for acting on economic issues, which constitute most of the action points formulated in last year’s strategic outlook on EU-China relations. But if it aspires to be a more assertive global player, Brussels will need to grow comfortable acting on political and security issues as well. In 2019, the EU did a good job at describing the China challenge. 2020 is the time to act.

The complete MERICS survey on European China Policy is available here.