1. A new era: Xi steers China’s economy on a different path

You are reading chapter 1 of the report "The party knows best: Aligning economic actors with China's strategic goals". Click here to go back to the table of contents.

Key findings

- China is contending for the central position in the global economic order and to establish itself as an innovation power. Xi’s new policies are responding to slower growth and perceived Western containment, but they also aim to establish foundations for a new development path for its economy.

- Beijing’s answer is a tech-centered agenda – to deal with a shrinking workforce, enhance productivity, and decrease reliance on the US and its allies.

-

China’s future development path is shaped by growing distrust between China and liberal market economies. In contrast to previous decades of economic integration and accepted interdependencies, in the new era risk mitigation is at the top of everyone’s agendas.

After four decades of market reform and global integration, China’s economy is at a critical juncture. It now faces the most challenging phase of economic development as a new growth model is needed to break through the middle-income trap and become more innovative and productive. The Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee in fall 2023 will shape China’s economic trajectory for years to come. At the Third Plenum in 2013, Xi Jinping introduced his priorities for political and economic reform: a careful balance between the role of the state and the market. Many abroad were hopeful he might be the reformer China needed, even as his reforms represented a compromise between the more liberal and more conservative forces in the party. Xi’s adjustments to China’s economic policies aim to deal with the negative side effects of what he terms “unbalanced and inadequate growth”, a legacy of the previous growth model. This includes, for example, a highly leveraged financial system and a real estate sector accounting for nearly 30 percent of GDP”. Simultaneously, they are also a response to perceived Western containment and its efforts to limit China’s access to technology.

Xi Jinping wants new kind of modernity for China by 2049, achieving key milestones and development targets by 2035. The path forward under Xi will lay the foundation for the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) aim of “national rejuvenation” – returning a strong and prosperous modern China to the center of the global economy and innovation by 2049. Achieving this with China’s special economic model – Socialism with Chinese Characteristics – would establish a system that can outcompete the liberal market economic system and prove that Chinese-style modernization can be dynamic and innovative. If successful, the CCP could establish China as the superior economic system. But there is also a real risk that the economy will hit a period of stagnation during Xi’s third term, as the country confronts a complex set of domestic and international challenges.

1.1 Policy priorities are unlikely to meaningful change even as economy is facing headwinds

At the start of his third term, Xi clarified his vision of how the CCP should reach its targets for the country. Over his first two terms, economic policy shifted towards political, ideological and security objectives. But 2022 marked a sea change for Xi’s policy priorities and their attendant trade-offs. Xi’s ideological views permeated economic policy – to the detriment of economic growth. To reverse the downturn after the prolonged lockdown of its “zero-Covid” policy, China has downplayed ideology in 2023, and “pragmatism” has returned to economic policymaking.

This is not a course reversal, but rather a matter of tone and timing. Despite softer language and a less ideological tone, the flurry of rules and regulations imposed in 2020-2022 to strengthen the party’s grip over the economy have not been abolished. They are simply taking a back seat to boosting investor and consumer confidence amid a disappointing post-Covid recovery. China’s leadership has gone into overdrive to woo foreign investors who have become wary of China, not only due to growth prospects but also to political dynamics – both in China and at home.

China is now an economic giant, accounting for around 20 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 30 percent of global manufacturing. Xi Jinping no longer feels bound to the foundations that guided his predecessors. In the past, leaders tolerated considerable risk in their domestic reforms in order to maximize economic development opportunities. These included the massive displacement of capital and labor with Zhu Rongji’s state-owned enterprise (SOE) reforms, or Deng Xiaoping’s agenda of opening up and pushing integration with the global economy.

This “gamble” has paid off, and Xi is setting his sights on taking China to a higher level of development and global influence. In pursuit of the second centennial goal (100th anniversary of the PRC / 中华人民共和国成立100周年), Xi has shifted the party baseline (党的基本路线) from focusing on economic development to coordinating development and security (统筹发展和安全). This marks a new direction that emphasizes party control over the free hand of the market and puts a greater priority on minimizing risks and achieving political and geopolitical goals than on economic development.

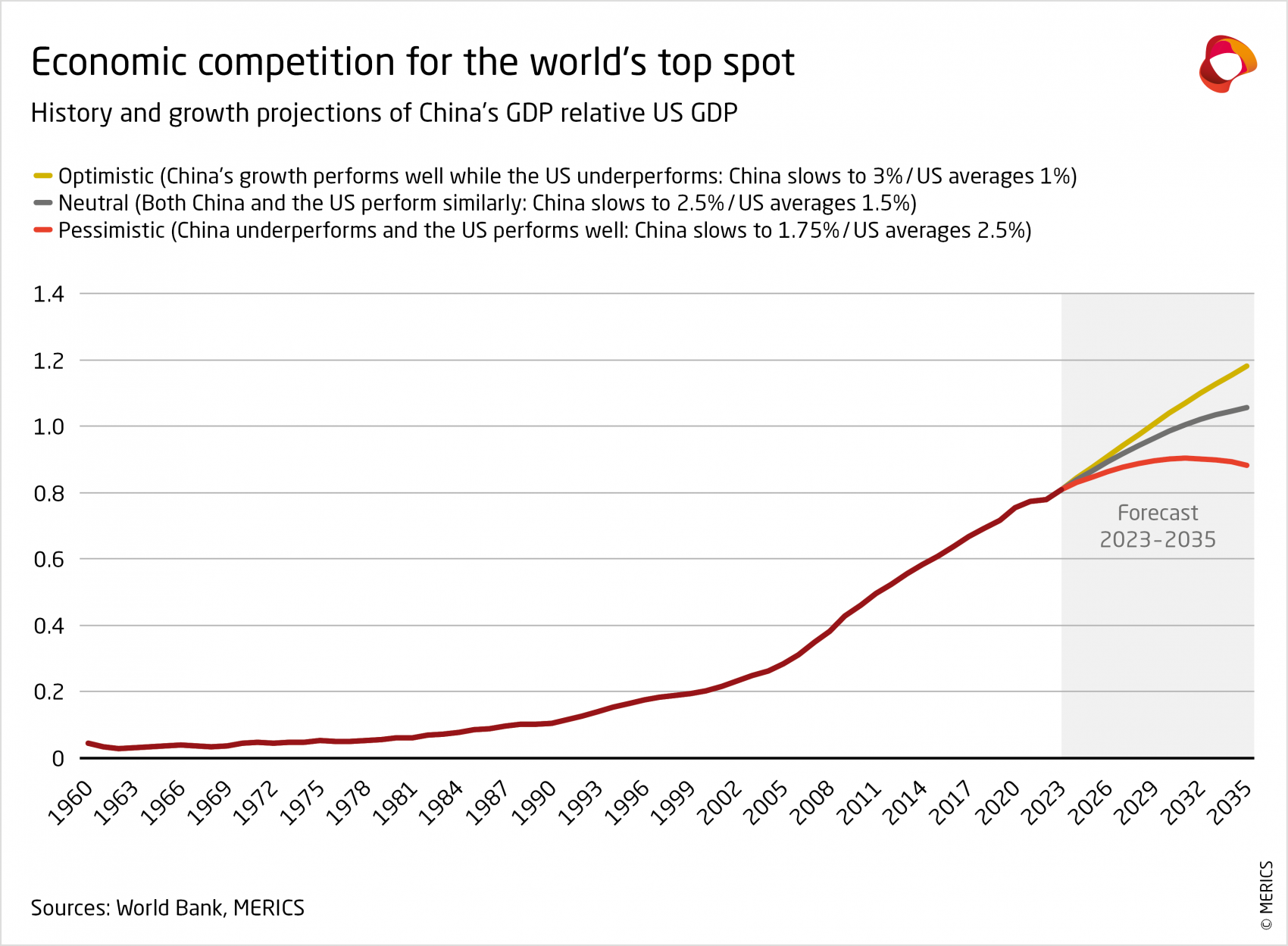

China’s economic policymaking in the last decade was characterized by an urgency to build an economy that could withstand external shocks. Increasingly, its policy priorities are geared toward a geopolitically oriented economy that is obsessed with US-China competition and deprioritizes the emphasis on social development. A key metric in measuring success is whether or not China can eclipse the US economy. This depends on many factors, including GDP growth in China and the US, inflation and exchange rates. This offers a range of possible outcomes (see Exhibit 1). Following years of strong growth, China’s next phase of “catching up” will be accompanied by slower growth. But success is also measured in relative terms: China sees the US and the West as in decline. Regardless of its relative size to the US economy, China is back on the world stage and will remain an economic heavyweight.

Globalization and economic relations with China are likely to be profoundly different in the future. This year’s Third Plenum will have historic significance comparable to the opening up and reform process that began in 1978 or the country’s WTO accession in 2001. But while China’s rise was largely seen as an opportunity in Europe and elsewhere, fundamental changes are at play that could – once again – shake up the world economy. The Third Plenum is taking place at an inflection point for China’s economy, with several key factors shaping its future development:

- A period of slower and more volatile GDP growth: China’s economy is undergoing an inevitable structural slowdown after a period of rapid growth. This requires adjustments to its growth model. Engineering a stable economic slowdown has become more difficult amid China’s disruptive policy shifts in response to external and internal challenges such as Covid-19, high debt levels and the prioritization of national strategic goals in face of rising geopolitical risk.

- Quickly rising innovation capacities that have yet to yield productivity dividends: China has made remarkable strides in boosting its innovation capacity, becoming a cutting-edge nation in a number of technologies ranging from traditional sectors such as high-speed rail to emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence. At the same time China’s total productivity growth has decelerated.

- China’s gravitational pull on the global economy: Despite slower growth, China is an economic heavyweight aiming to challenge the global economic order, establish itself as an innovation power and an expand its global economic footprint.

- The politicization of globalization: Geopolitical risks and efforts to strengthen economic security in China and worldwide are shaping international global supply chains and innovation.

- Non-convergence with liberal market economies: China is seeking its own development path that serves the goal of “perfecting” the Chinese socialist system. Under the leadership of the CCP, new theoretical foundations of economic development are being created with an emphasis on tech-centered economic nationalism.

1.2 Ideology meets economic realities: trade-offs in Xi’s tech-centered economic nationalism

Looking forward, a key challenge will be reconciling Xi’s national strategic priorities with economic prospects, including jobs and income. China is neither ending its era of reform and opening up nor returning to the closed Mao years that preceded it. Instead, its internal reform and external opening agendas are taking place under fundamentally different conditions with new political parameters, incentives, and drivers. In the past, internal reform was heavily driven by maximizing development opportunities, while external opening was about accepting interdependencies to accelerate growth and expand export opportunities with liberal market economies.

Under Xi, internal reform is about fine-tuning control of the economy to steer it through domestic hard times with an aging population and sluggish productivity growth. External opening aims to reduce interdependencies with liberal market economies that recently began to restrict China’s access to their key technologies. Xi’s answer to these problems is technology – to deal with a shrinking workforce, enhance productivity, and decrease reliance on the US and other countries Beijing believes to be Washington’s pawns.

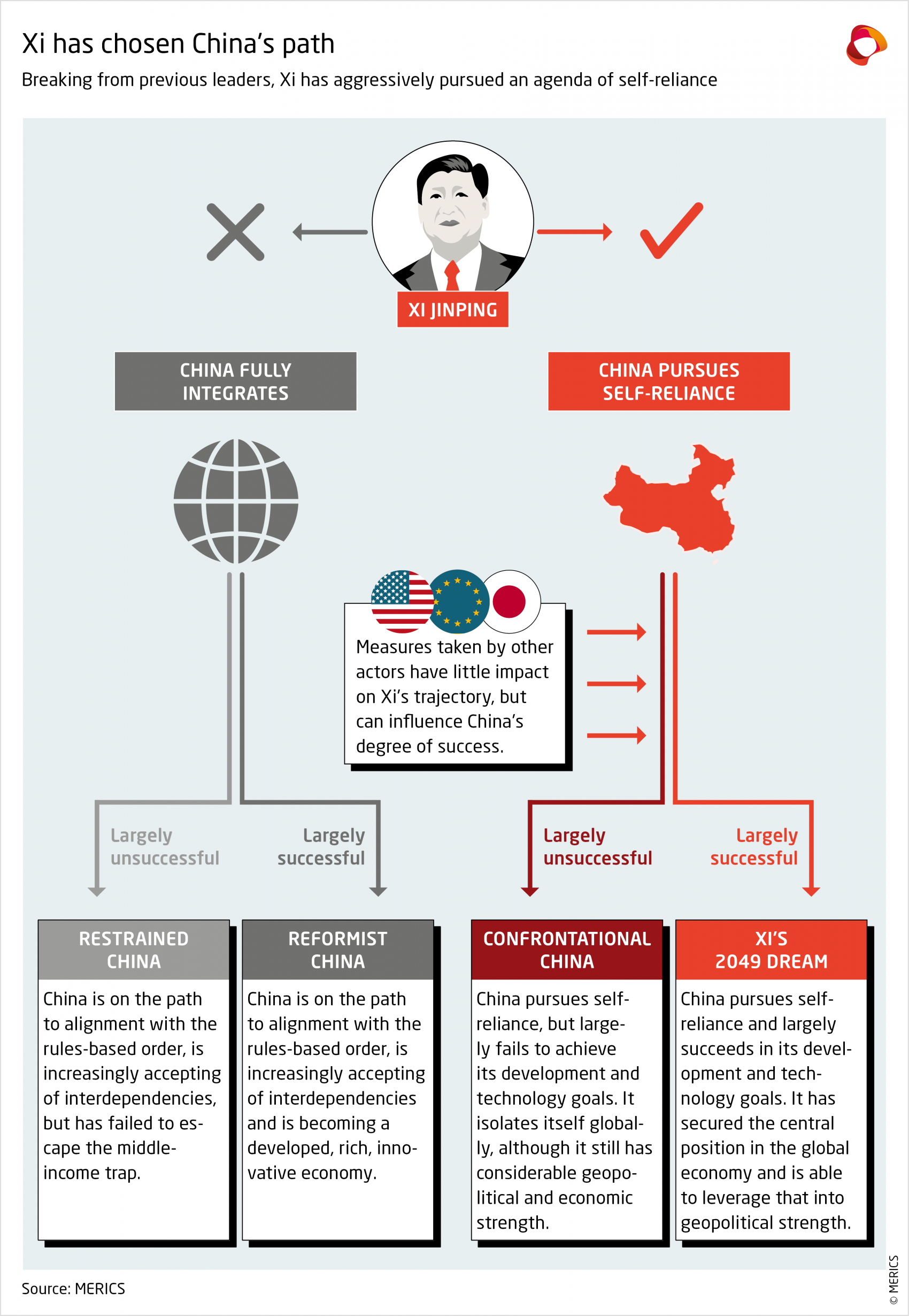

The current technology-centered agenda has set the country on a clear trajectory, though its success is far from guaranteed. The sustainability of Xi’s path will be put to the test when ideology-driven ambitions clash with economic reality. For example, despite China establishing itself as a global innovation power, total factor productivity growth has slowed from 22 percent between 2003 and 2011 to only 5 percent between 2011 and 2019.1 Aligning national strategic goals with the national wellbeing is causing tensions. Another example is the popular backlash in November 2022 over economically stifling zero-Covid policies triggered a rapid course correction, with further corrections taking place amid a sluggish economic recovery in 2023. But this is no paradigm change or return to economic pragmatism. There may be bigger tests ahead if Xi continues down his chosen path and the strategy fails (see Exhibit 2).

1.3 Xi has chosen China’s trajectory, but other actors are choosing how to respond

While countries may only exert limited pressure on China to deviate from Xi’s charted course, there are plenty of other ways to affect its chances for success. Somewhat oversimplified, countries with liberal market economies may continue to give China access to their markets and technologies, or they may further restrict it. China, on the other hand, may accept economic and technological interdependencies with liberal market economies, or further pursue self-reliance. The issue is that every step China takes toward self-reliance pushes liberal market economies to restrict China’s access to their markets and technology. In turn, this drives China further down the road of self-reliance.

In that sense, China and liberal market economies are on a path toward long-term, profound disruption to economic and technological globalization, despite likely worse outcomes for all actors. The net positive result for all would be to restore globalization with all sides willing to accept common rules and norms as well as interdependencies. This goes as much for the US, EU and Japan depending on China as it does China depending on them.

But the disincentive for China to reverse course and abandon its self-reliance campaign is that liberal market economy countries might cut it off anyway, leaving it too far behind to catch up. The disincentive for liberal market economies to allow China access to their markets is that Beijing might maintain its path to self-reliance and succeed, unleashing China’s geopolitical power and “replacing” them in the global economy.

The problem of renewed globalization is that, for each side, the net gain from the best-case scenario is less beneficial than the net damage is from the worst-case scenario – meaning countries have more incentive to take damage-limiting action than to pursue risky opportunities. Furthermore, the growing distrust between China and liberal market economies and previous actions by both China and the US have put everyone in a poor position.

1.4 High stakes: China’s economic development is shaping the global order

The evolution of China’s political economy, market reforms and integration in the global economy under Xi will shape its economic path forward. Its development also very much depends on how advanced economies control access to technology. Success or failure not only depend on China’s own performance but how liberal market democracies respond to the current structural shifts shaking up the global order.

Dealing with an economically large, technological capable, and systemically non-convergent China requires a deep understanding of the structural shifts in China’s next stage of development:

- What are the key building blocks of China’s political economy under Xi’s ideology?

- Which party and state measures are used to steer economic actors?

- How will the CCP attempt to secure the socio-economic base?

- How will innovation look under an increasingly authoritarian regime?

- How will China pursue global integration?

Our baseline scenario is that China will continue down Xi’s chosen path, at least as long as he is in power, with continued uncertainty over the success or failure of his strategy. Keen to ensure success, Xi recently codified his own economic thought in a new development model worthy of his “New Era.” This vision aims to contend with, as he puts it, “changes unseen in a century,” and is matched with a growing set of measures to shape the economy. These party and state measures aim to operationalize his ideology and galvanize all economic actors to strive for strategic goals – all to enable the success of the 2049 dream.