5. Xi’s emerging social contract puts strategic objectives first

You are reading chapter 5 of the report "The party knows best: Aligning economic actors with China's strategic goals". Click here to go back to the table of contents.

Key findings

- The transition towards a consumption led growth model is taking the back seat. Achieving industrial policy objectives takes precedence over advancing socio-economic targets, so long as the economic baseline is held.

- Despite Xi’s ambitious social reforms, advancing structural socio-economic change and redistribution have never been the priority for CCP since it embarked on economic reforms.

- Under Common prosperity there is discontent with those displaying excessive wealth and an expectation for companies to take on more social responsibility.

- Aligning strategic priorities with jobs and income is becoming more difficult as China deals with a more demanding middle class and its needs and wants.

- Ideology and geopolitical rivalry are nurturing a more repressive political economy that may well run counter to the expectations of a large middle class.

China’s economic transition has been a remarkable success. In the process, over 800 million people have escaped poverty.58 Just in time for the CCP’s centennial in 2021, Xi declared the end of extreme poverty. The annual income of at least 100 million people had exceeded RMB 4,000 – China’s definition as the rural poverty line. In 2022, GDP per capita reached USD 12,720, putting it close to the World Bank’s definition of a high-income country of USD 13,845.59 But this still leaves China below Bulgaria (USD 13,772) and Romania (USD 15,892), the countries with the lowest GDP per capita in the EU.

Solely focusing on national GDP per capita levels in China might be misleading as it is already an innovation power to reckon with. In a large economy like China, various development stages take place simultaneously. Already 42 percent of its population lives in regions that would be categorized as high income by the World Bank. Jiangsu, Fujian, Zhejiang and Guangdong all have a GDP per capita greater than USD 15,000 in 2022. Together, their population is over 330 million, giving China a very sizable middle class.

Despite this remarkable success in improving the well-being of society, China’s economic policies have remained geared toward supporting industry in pursuit of greater technological sophistication. Reaching national strategic goals requires large capital investments in infrastructure, production capacity and science and innovation. Empowering the autonomy of private households’ consumption patterns is not compatible in a system that seeks greater centralization and control – after all, consumers might not buy what the party wants them to. This sets limits to the decade-old demands for rebalancing the economy to rely less on investment. In Xi’s economic logic, it is a strong capacity to provide effective supply that creates jobs and income – and from that follows demand.

The type of socialism that Xi Jinping envisions for China emphasizes ideology and nationalism. A fundamental part of this are collectivist principles as an important feature of China’s economic system. This means that the nation’s interest supersedes that of the individual. While individuals are not yet only seen as a means to an end by the CCP, more repressive structures in the political economy are limiting their corridors of economic activity.

Advancing authoritarian elements as a key principle of governance under the leadership of Xi Jinping is leaving its marks on the socio-economic structure of the country. As in other parts of China’s economy, the CCP is advancing its position and guidance over economic actors. This does not bode well for a substantial shift in China’s growth model toward more household consumption and has significant implications for China’s development path.

5.1 Consumption-driven growth fails to lift off

One of Xi’s signature policy agendas, The dual circulation strategy, is centered around just that. The core principle is to shift China from its previous model of export- and investment-driven growth to one that is primarily fueled by domestic consumption, and in which exports play a supplementary role. However, broad acknowledgement that such a shift toward consumption-driven growth is necessary does not inherently facilitate that transition. There are other priorities to consider, and Xi has clearly ranked consumption-driven growth as a second-tier goal.

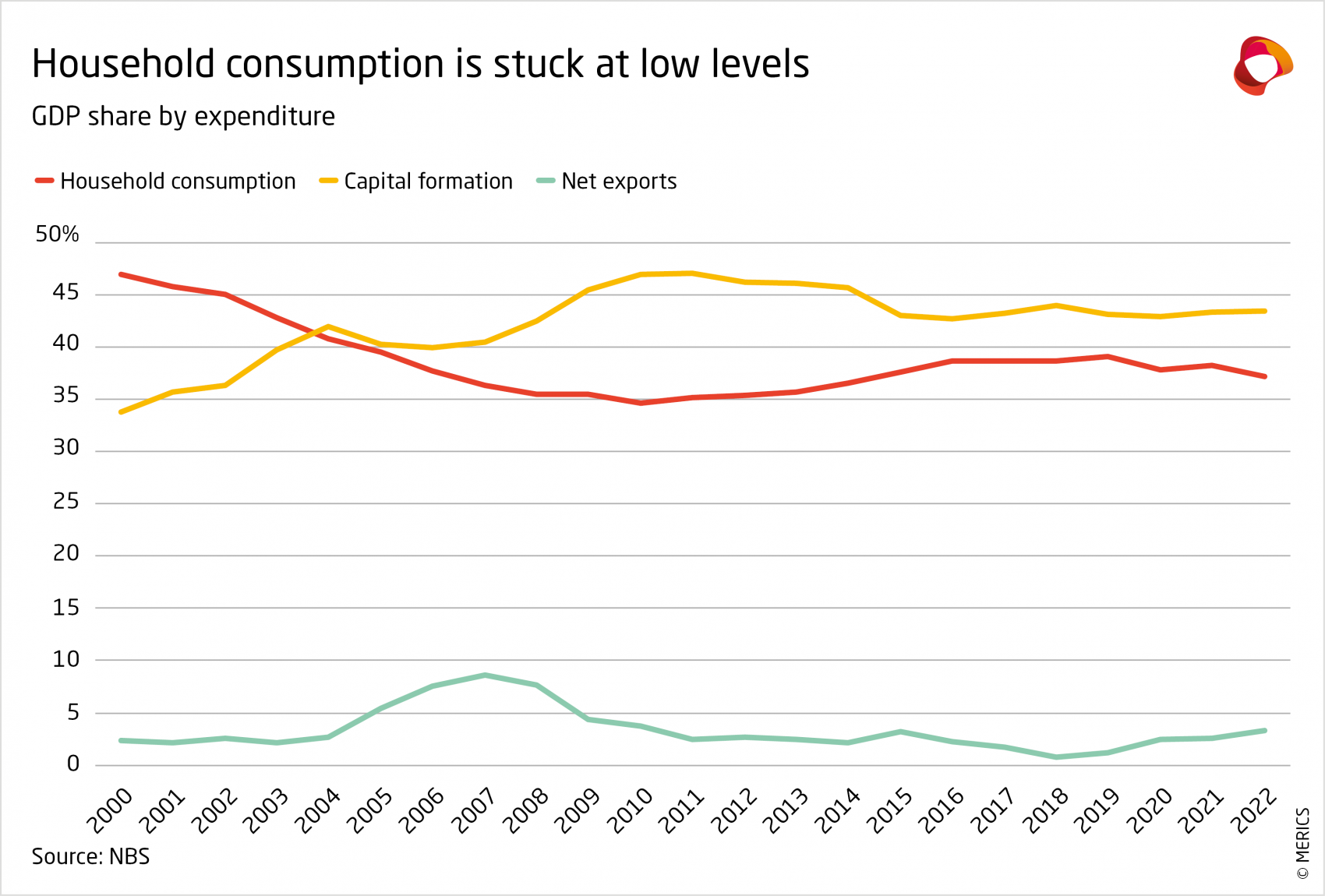

Countries with higher government control over the economy have generally lower degrees of private consumption.60 The household consumption share of GDP has barely improved since Xi’s first term in 2013 – going from 34.3 percent in 2010 to 38.5 in 2021, basically the same level over the past five years. Despite a long debate on the transition to a more sustainable growth model, investment remains the most important element in the economy. This should not come as a surprise as achieving industrial policy objectives takes precedent over advancing socio-economic targets. A higher share of consumption and the autonomy of households would counter efforts toward greater centralization of China’s economic system favoring industrial policy (see Exhibit 11).

The household consumption share of GDP for countries classified as middle income by the World Bank is typically around 50 percent while for high income countries the share is around 60 percent. In isolation, the failure of the dual circulation strategy to drive change might suggest a policy failure, but in the broader context of Xi’s economic policy making, it is rather a failure caused by tradeoffs. From the perspective of Xi’s economic thought, however, a low household consumption share should be understood as a feature of China’s economic system rather than a structural problem.

5.2 The rebuttal of the welfare state: socio-economic indicators stagnate under Xi

Advancing socio-economic policies and redistribution have not been the mainstay of the CCP since it embarked on economic reforms – and are not under Xi Jinping either. Zhu Rongji ended the Mao-era social safety net of the company-level work unit (单位) during the reform of SOEs in the 1990s. Disbanding the “iron rice bowl” was replaced by a laissez faire social system akin to a neoliberal economy.61 Any substantial rebalancing effort would require a meaningful redistribution and increased social expenditure by the government which would come at the expense of investments in expanding manufacturing capabilities and innovation. This requires change to be institutionalized rather than a campaign-style approach such as battling extreme poverty.

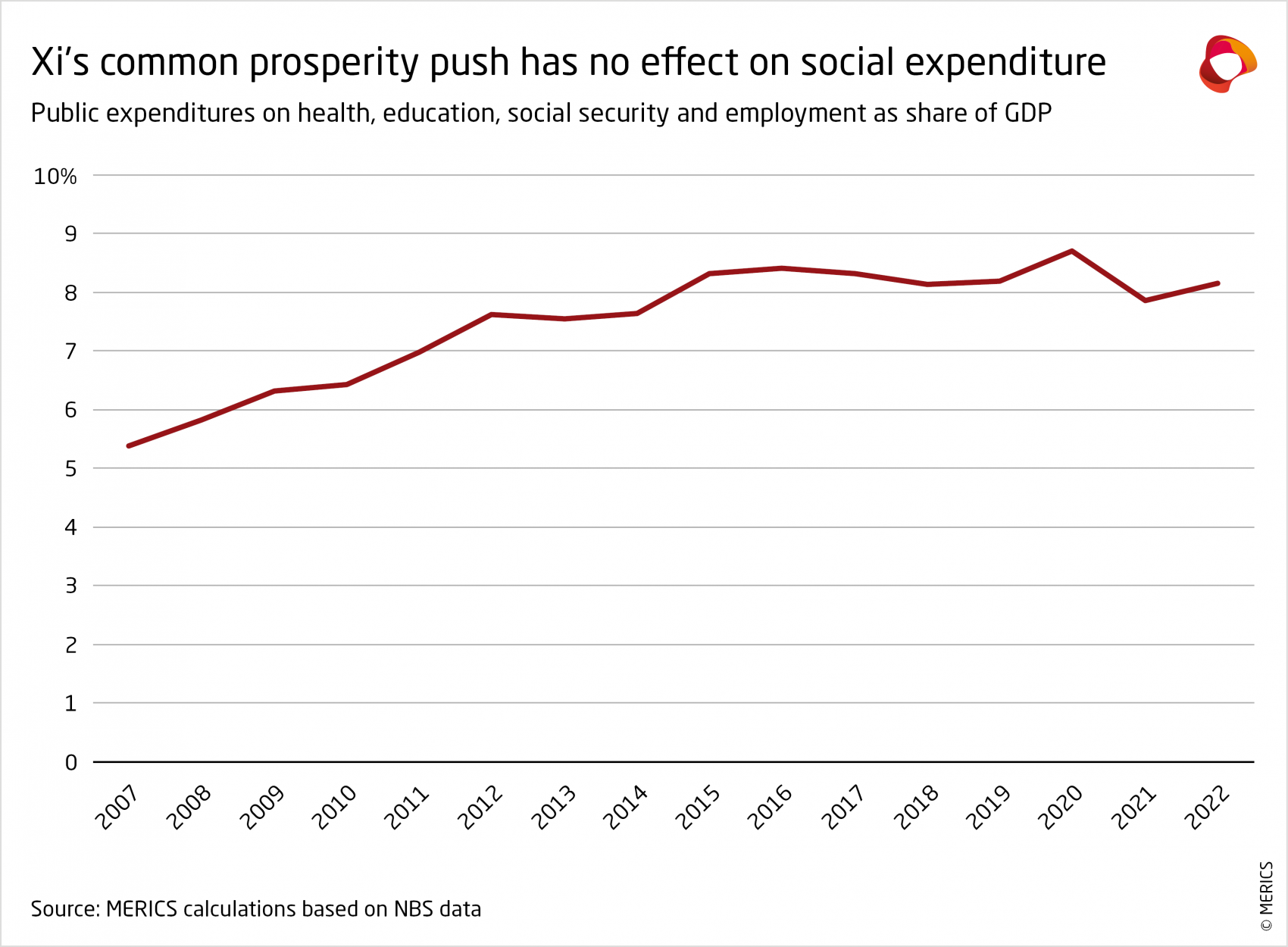

These priorities are unlikely to change anytime soon under Xi Jinping despite ambitious social reforms announced in 2013. Public spending on health, education, social security, and employment largely remained unchanged in Xi’s first two terms, reaching 8.1 percent in 2022. Xi has inherited many of the problems of previous leaders, but despite some lip service to structural reform he continues to kick the can down the road. Addressing these long-lasting structural issues will become even more pressing as GDP growth slows, society ages and the working population shrinks further from its peak in 2015, and highly leveraged local governments struggle to fund social services (see Exhibit 12).62

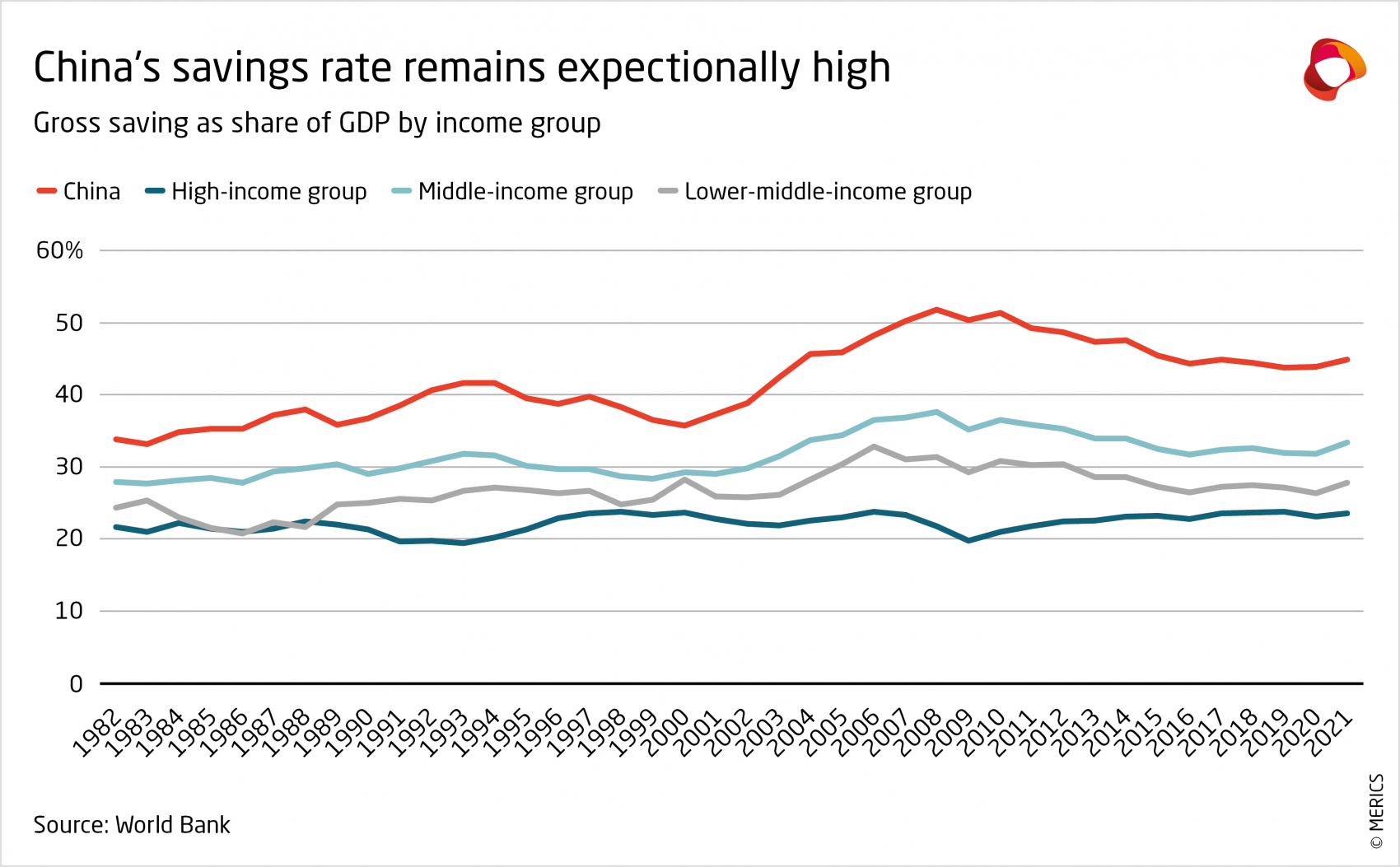

The lack of a proper social safety net helps explain China’s exceptionally high savings rate. Households save money for health care or retirement rather than consume. High saving rates in turn promote an investment-led growth model as it facilitates cheap capital. Savings as share of GDP halve held steady at levels close to 45 percent since 2013. China’s saving rate is almost in a league of its own and far higher than for middle- or high-income countries as classified by the World Bank. The impression of hyper-consumption in China’s modern mega-cities or online retail frenzy do not reflect the macroeconomic reality but rather a snapshot of the society – and entrenched inequality.

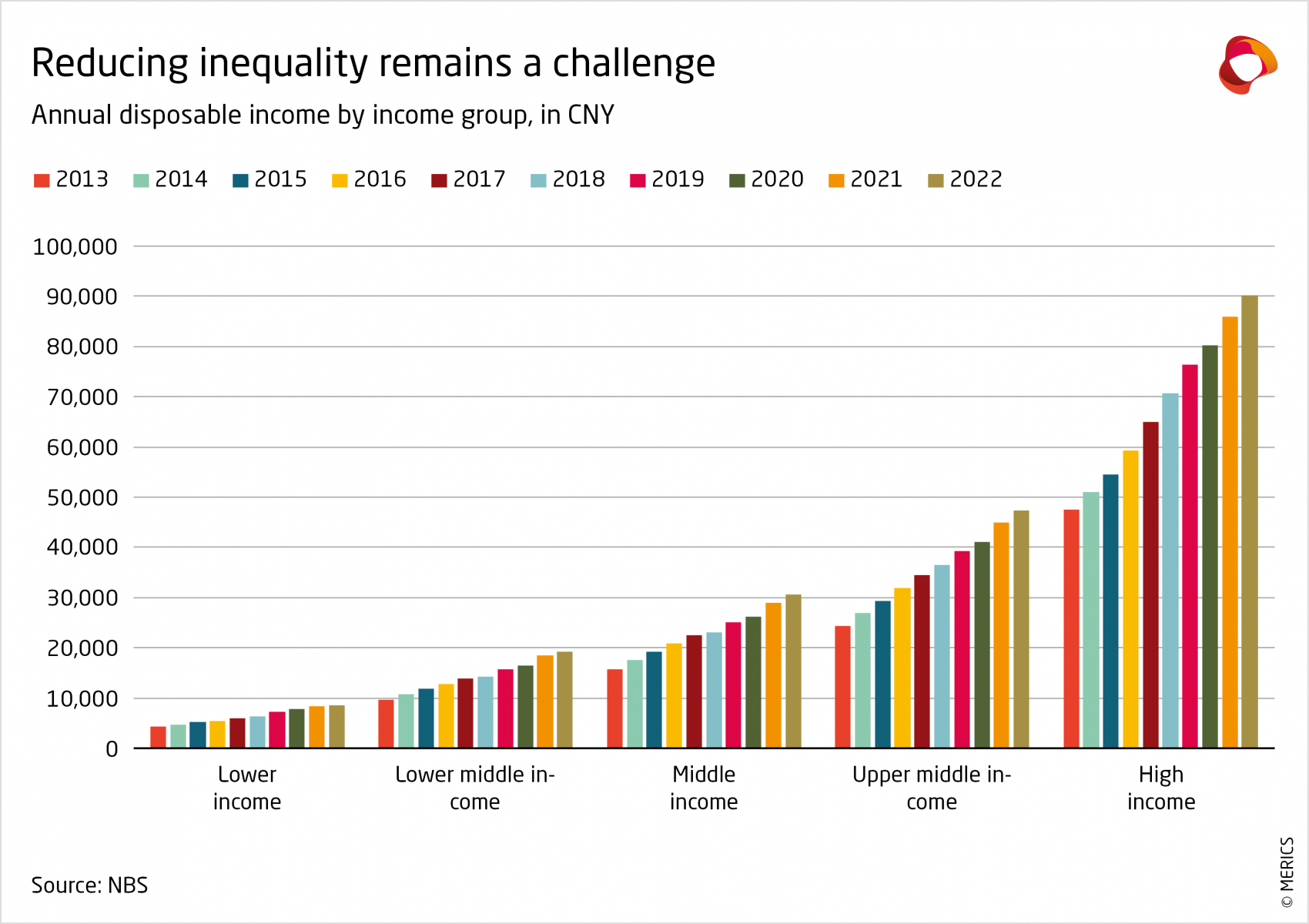

China’s inequality has remained persistent but has been less of a policy issue for as long as economic growth remained strong enough to improve the lives of all income groups. This has given the CCP the liberty to set economic policy priorities other than strengthening the social system (see Exhibit 13 and Exhibit 14).

5.3 Common prosperity is more symbolism than structural change

The failure to direct more income to households belies another core tenet of Xi’s economic ideology in practice. Common prosperity re-entered the lexicon in 2021 when it was wielded alongside the broader crackdowns on digital tech and real estate. Many initially expected that large-scale redistribution was in store, but this failed to materialize beyond some talk of tertiary distribution – the redistribution from wealth via donation or charities. Companies got the message to take on more social responsibility by expanding philanthropic work, including donating to those in need and setting up funds focusing on rural development and announcing measures to reduce the income gap within companies.63

Under Xi Jinping, the flashy display of wealth by business elites is becoming less fashionable – and potentially risky. China’s entrepreneurs could be facing consequences similar to local officials during the anti-corruption campaign in the early days of Xi’s rule. In response, officials could no longer hold fancy banquets or be seen with expensive watches. There is an increasing expectation of modesty and the need to demonstrate a role in developing the nation. As a result, China’s billionaires donated a record sum of USD 10 billion in 2022 – more than a drop in the bucket.64

Common prosperity has been used alongside pressure on China’s most innovative companies to put their capital and expertise to use in achieving national strategic goals, like closing the technology gap. But Common prosperity is not about deriving prosperity for the working class at the expense of higher taxes on the wealthy or increasing costly social services. Xi’s policies, including a crackdown on private companies and elites, in part resemble populist policies introduced by disgraced former senior CCP official Bo Xilai in Chongqing, who was convicted of embezzlement, but they do not concretely address key issues including redistribution and inequality.65

So far, his efforts pale in comparison to those under former President Hu Jintao. Hu expanded labor legislation, including contract law and a more serious implementation of minimum wage and improved access to medical insurance for migrant workers, although these efforts lost steam at the end of his term in 2012.66 Ironically, Xi’s vision of Chinese socialism comes with a rejection of Western-style socialism with its stronger role for the state. Instead of deepening institutional reforms, the responsibility of providing is left in large part to individuals themselves while the state contribution is kept to a minimum. Stronger guidance on companies under Common prosperity is little more than signaling right now, but if accelerated, could shift toward a larger burden falling directly on companies.

This sentiment is also captured in the case study on Tencent at the end of this chapter. The company was front and center during the consumer internet/platform crackdowns of 2020-2021, and it has been pushed by Beijing to align its strengths towards supporting the real economy. Furthermore, Beijing has heavily punished the gaming side of Tencent’s operations, with tight regulations not only limiting approvals for new games, but for restricting gaming time for some users. The result is that the company has been cowed domestically and is strategically going overseas to make up for the lost business opportunities within China.

5.4 The new social contract means contributing to national rejuvenation

Policies under Xi Jinping increasingly appear motivated by non-economic targets that do not aim to increase profits or the welfare of individuals and private companies, but rather to promote self-reliance and national power, including military power. Allocating national resources to building a welfare state is a luxury the CCP does not want to pursue in a time of growing systemic rivalry with the US. Increasingly, the economic beneficiaries of China’s development in past decades, notably entrepreneurs, the wealthy and the middle class, will now be expected to be grateful to the party for allowing them to be far better off than the hard-working generations before them. The new message is: Don’t become complacent. Tighten your (economic) belts and roll up your sleeves to do what is in your power to rejuvenate the Chinese nation.

Aligning national strategic priorities with jobs and income is becoming more difficult as China deals with a more demanding middle class and its needs for jobs and income. This comes as social fault lines are becoming more complex. Youth unemployment reached record levels of over 20 percent in Q2 2023, yet companies are struggling to fill vacancies in factories.67 One reason for this is a growing mismatch of skills and expectations. Workers with the vocational skills needed in manufacturing are scarce. On the other hand, not every university graduate will become a high-profile scientist helping China close the technology gap. Encouraging youth to work in the countryside seems to be a hard sell for an aspiring future generation.68 Most young urbanites most likely do not expect to return to rural life, nor are they keen to work in 3D manufacturing jobs (dirty, demanding, difficult).

Creating a large middle class, one of China’s biggest economic reform successes, now looks like a potential vulnerability for the CCP. There is a real risk that parts of society will see a stagnation, or even a possible deterioration, in economic well-being. The CCP will need to respond to these demands of the middle class. It has already shown a return to pragmatism following intense economic pressure built up during the three-year zero-Covid policy. The CCP must control social economic risks, using, for example, extensive party and state intervention in sectors like real-estate, most infamously with the debt-ridden property giant Evergrande, but also to provide an economic baseline that ensures employment and income to satisfy the minimum needs of the majority of society.

Beijing views the role of most companies as holding that economic baseline. This includes companies with a limited role in driving forward high value-added production or helping in the innovation drive to close key tech gaps. One example, GAC-Toyota, a Sino-Japanese JV internal combustion engine automaker, is covered in the case study below.

The greater importance of ideology and geopolitical rivalry are nurturing a more repressive political economy which tends to be less responsive to a moderate society.69 Under such a system, social and regional divisions are likely to become a major issue going forward. Though more policy changes attempting to address the resulting problems can be expected in the context of Common prosperity, the overall prioritization of national strategic goals over economic growth seems to be a new hallmark of China’s economic system.

Case Study: GAC-Toyota JV shifts from tech provider to economic baseline holder

Gregor Sebastian

GAC-Toyota is a JV between Chinese SOE Guangzhou Auto (GAC) and Japanese car giant Toyota, focused on making passenger vehicles. Both partners have additional, competing automotive JVs and production bases in China. Unlike in the past, Toyota is no longer viewed by Beijing as a technology provider, and such sino-foreign automotive JVs that are not fully committed to EVs will play a limited role in the future – holding up the economic baseline until they are phased out over time.

From Beijing’s point of view, the strategic role of such JVs has shifted in recent years. Initially, Beijing saw these primarily as a means to help Chinese carmakers move up the value chain by introducing Japanese car-making technology and knowhow into China. But China’s shift to EVs means Toyota is no longer seen as such an important technology partner. Nonetheless, the JV continues to fulfill several important functions such as contributing to economic growth and promoting employment and tax payments. What’s more, it continues to serve as an important anchor for Japanese suppliers to localize production in China.

GAC’s state ownership gives Beijing influence through JV requirements

Market access restrictions: To promote the development of Chinese carmakers, Beijing has restricted the access of foreign carmakers, including Toyota, to China’s market. High tariffs have made exporting to China unpalatable but producing locally meant entering into a JV with a local partner and sharing technologies and knowhow.

Promoting electric vehicles: Beijing has reduced its technological reliance on the JV by promoting EV technologies that had not yet been dominated by foreign carmakers such as Toyota. The government incentivized carmakers to develop and produce new energy vehicles (NEVs) using carrots, including subsidies, and sticks, such as a production quota. In an initial pilot phase, hybrid vehicles had been trialed, but fearing future dependency on Japanese carmakers like Toyota, Beijing excluded hybrids from the NEV definition.70

The loss of relevance of hybrid technology made Toyota more willing to share its knowhow. In 2019, the Japanese carmaker even offered patented hybrid technologies free of charge to Chinese producers in the hope that hybrid vehicles would be taken up more widely. In 2020, Toyota licensed its hybrid tech to GAC.71 The JV also announced additional investments for a new NEV plant, further promoting growth in Guangzhou.72

GAC-Toyota is still important for Beijing in promoting growth

The initial goal of promoting technology transfer from Toyota to GAC has partly worked. While GAC is not yet an internationally competitive carmaker and has lagged Toyota in producing internal combustion engine vehicles, it has fared among the best in Chinese state-owned carmakers. Its own brands in the ICE (Trumpchi brand) and EV (Aion brand) have been successful in China. GAC own brands have benefitted from the knowhow and engineering expertise of the Toyota JV. Indeed, with the shift to NEVs, a “reverse technology transfer” has taken place, as jointly produced EVs have used a GAC-developed electric powertrain.

The draw of Toyota has also helped China attract investment from Japanese and other international suppliers. Japanese Nidec formed a JV in 2019 with a GAC subsidiary to produce electric motors for GAC.73

Beijing’s perspective on the JV has shifted from seeing it primarily as a source of technology to considering it more as a means of maintaining an economic baseline. Nevertheless, Guangzhou’s robust local economic prowess and GAC’s capacity to compensate for potential employment losses resulting from the JV have greatly diminished its significance over time, even as an economic baseline.

Case Study: Tencent’s best lines of business are under the most political pressure

Aya Adachi

The Shenzhen-based tech conglomerate Tencent has many lines of business, and has experienced some of the most intense application of Beijing’s party-state toolkit after initially benefiting from protection from foreign tech giants. The bulk of its products are consumer internet in nature: social media companies like Wechat and Weibo, entertainment, digital payment systems and gaming; and have thus been highly exposed. Despite being one of China’s most profitable and innovative companies, the firm has been so besieged to change its behavior at home that it is now seeking foreign markets to balance out the domestic market’s now-diminished growth potential.

From “value-chain climber” to “the untrusted,” Tencent has suffered most in its gaming sector

Once a boon for consumption growth on paper, Tencent has come under heavy pressure not only for failing to contribute to key national strategic goals, but for allegedly dragging them down. Tencent’s data collection across its lines of business likely presented a comprehensive look at many Chinese citizens and their habits, which are seen by authorities as bad enough to become a central focus of the platform crackdown. Tencent has channeled its resources and research capacity to work on, from a stand point of national interests, not-so-important social media, gaming, and entertainment. Worse yet, those very products have proven unwelcome distractions for students whom the party-state expects to focus on their studies, and for young people who, instead of playing video games, should be contributing more to China’s rejuvenation.

Tencent was hit by the tech crackdown and a raft of anti-trust and gaming rules

Golden shares: As a major data-collecting and content-creating/distributing company, Tencent joined firms like Alibaba in having golden shares carved out by state-affiliated en- tities providing them with a disproportionate influence over operational decisions despite only holding a minimal share of equity.

Anti-trust fines: Tencent has been hit with multiple fines: for failure to comply with an- ti-monopoly transaction disclosure rules, for violating “concentration of business opera- tors” rules, and on 12 charges of violating the anti-monopoly law.

Anti-trust M&A blocked: In July 2021, SAMR blocked Tencent’s plan to merge Douyu and Huya, two video game live-streaming websites it controls. SAMR said that Huya and Douyu’s combined market share in the video game live-streaming industry would be over 70 percent if the merger went ahead.

Gaming-specific measures: In 2021, Beijing temporarily stopped approving gaming li- cences for 9 months. Between July and December 2021, around 14,000 small developers closed down. It was only in April 2022 that approvals came through for a mere 45 games.

Prime example of Beijing’s innovation hopes and containment fears

Beijing put tough curbs on gaming in 2021, laying waste to the once-booming industry and shaving over half of the market value of sector leaders like Tencent Holdings and NetEase Inc and shrinking the world’s biggest gaming market for the first time. In 2020 and 2021, Tencent’s Hong Kong-listed shares sank some 60 percent. The company has been so thor- oughly beaten down in its home market that it is now looking overseas for growth, even though China’s gaming market is the world’s largest, with considerable growth potential. The company is trying to adjust to the more restrictive environment, this reflects a certain unease about the political influence over its operations.

Since 2020, the company has proactively sought M&A’s overseas, both to pursue legitimate growth markets, but also to offset the quickly diminishing home market opportunities in China. Tencent has expanded abroad, with 44 deals in 2021, up from 17 the year before, across industries such as gaming, ecommerce, healthcare and fintech. Finally, the company is now embracing an “off the radar” strategy: Several venture capitalists told the Financial Times that Tencent had recently requested its name be omitted from press releases for start- ups’ new funding rounds.