Chinese investment rebounds despite growing frictions - Chinese FDI in Europe: 2024 Update

Report by Rhodium Group and MERICS

Key findings

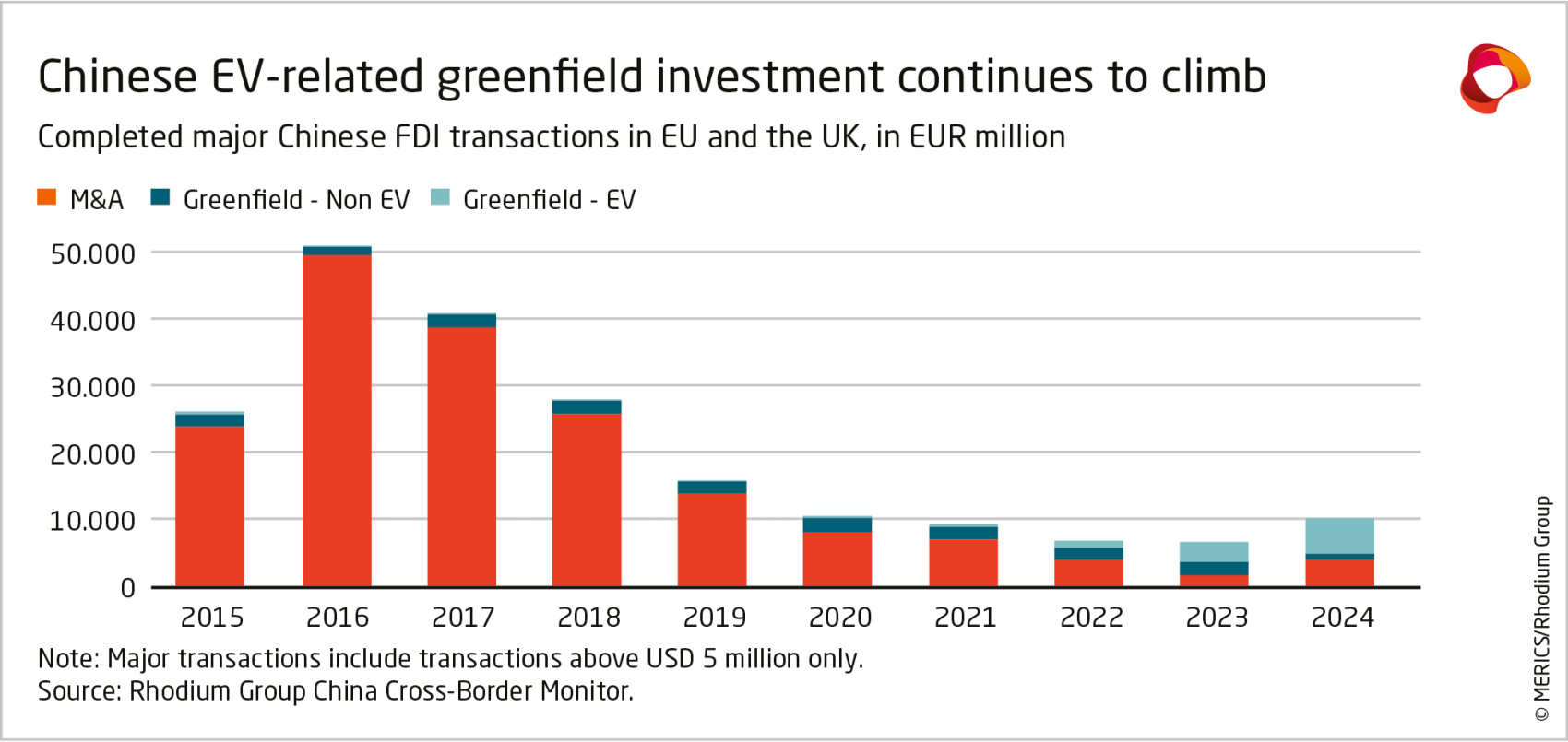

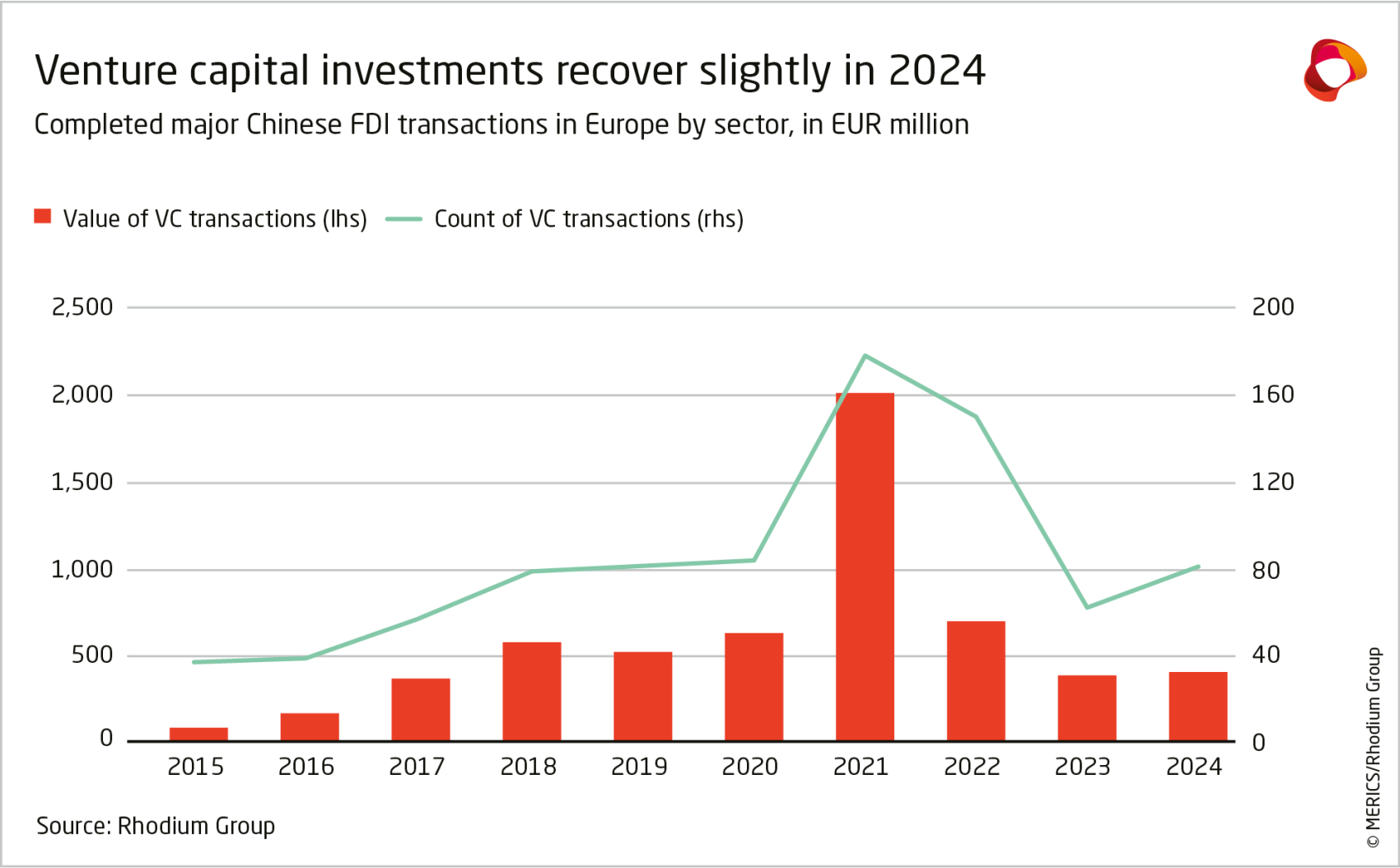

- Investment rebounds for the first time since 2016: Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU and UK reached EUR 10 billion in 2024, rising 47 percent from the previous year. Europe remained the leading destination for Chinese investment in high-income economies, drawing 53.2 percent of all Chinese FDI in such markets. In 2024, the EU and UK’s share of total Chinese FDI also rose to 19.1 percent, the first significant increase since 2018.

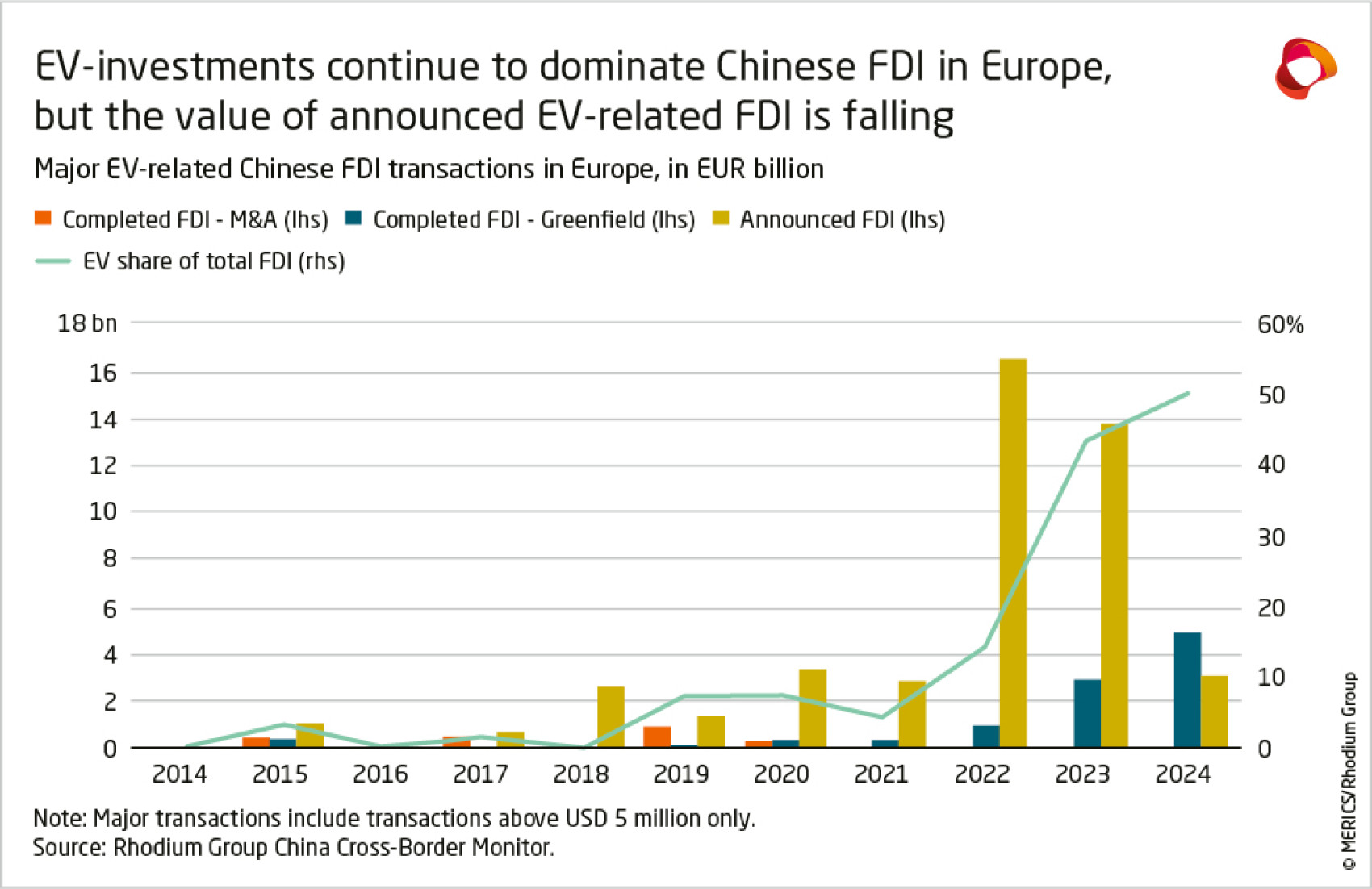

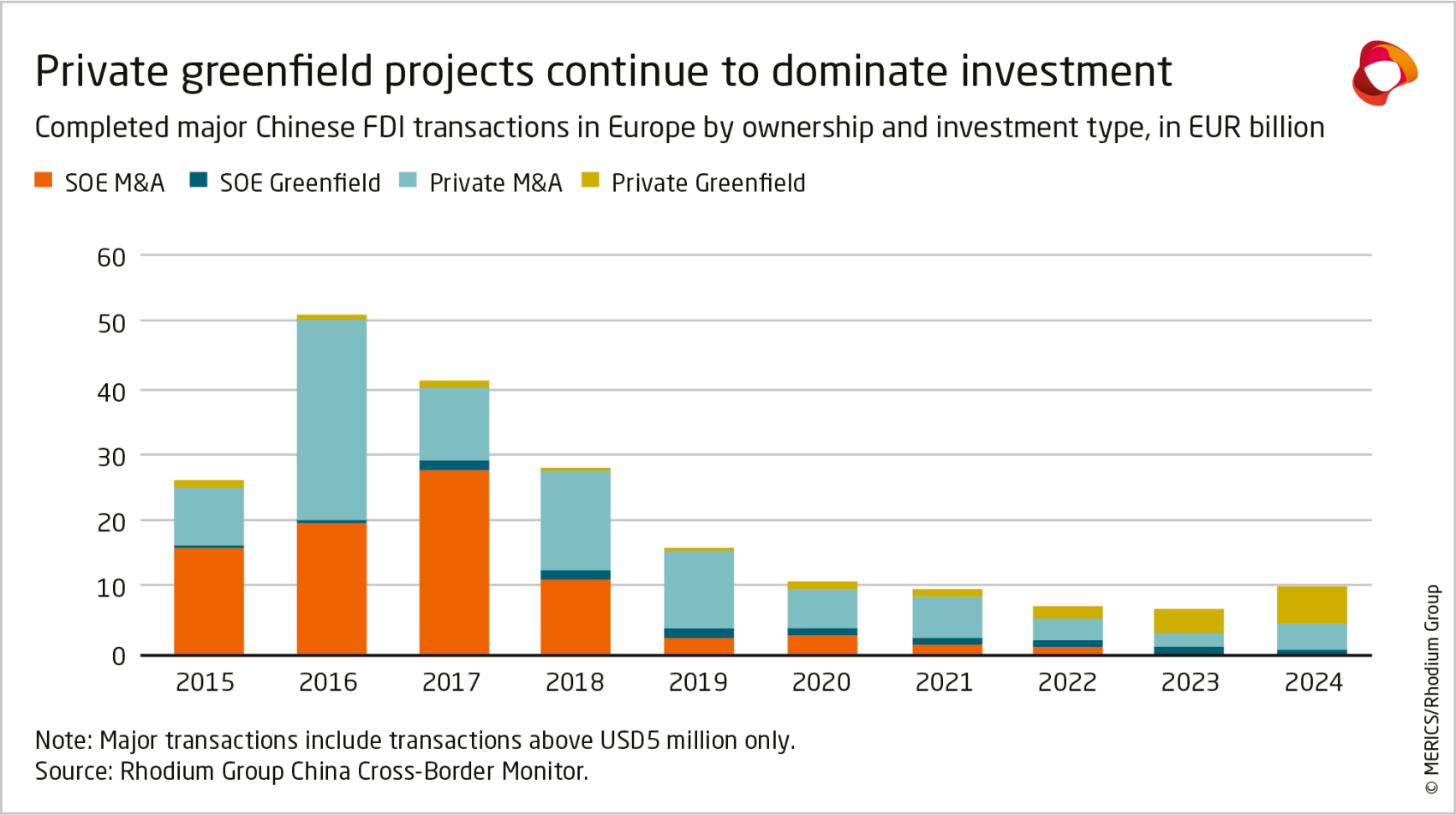

- The recovery is fueled by record greenfield investments and stronger M&A: Greenfield investment grew for the third consecutive year, rising by 21 percent year-on-year and hitting a record high of EUR 5.9 billion. It remained the dominant form of Chinese investment in Europe, but an improvement in M&A, which jumped 114 percent year-on-year to EUR 4.1 billion, also contributed to lift overall investment levels.

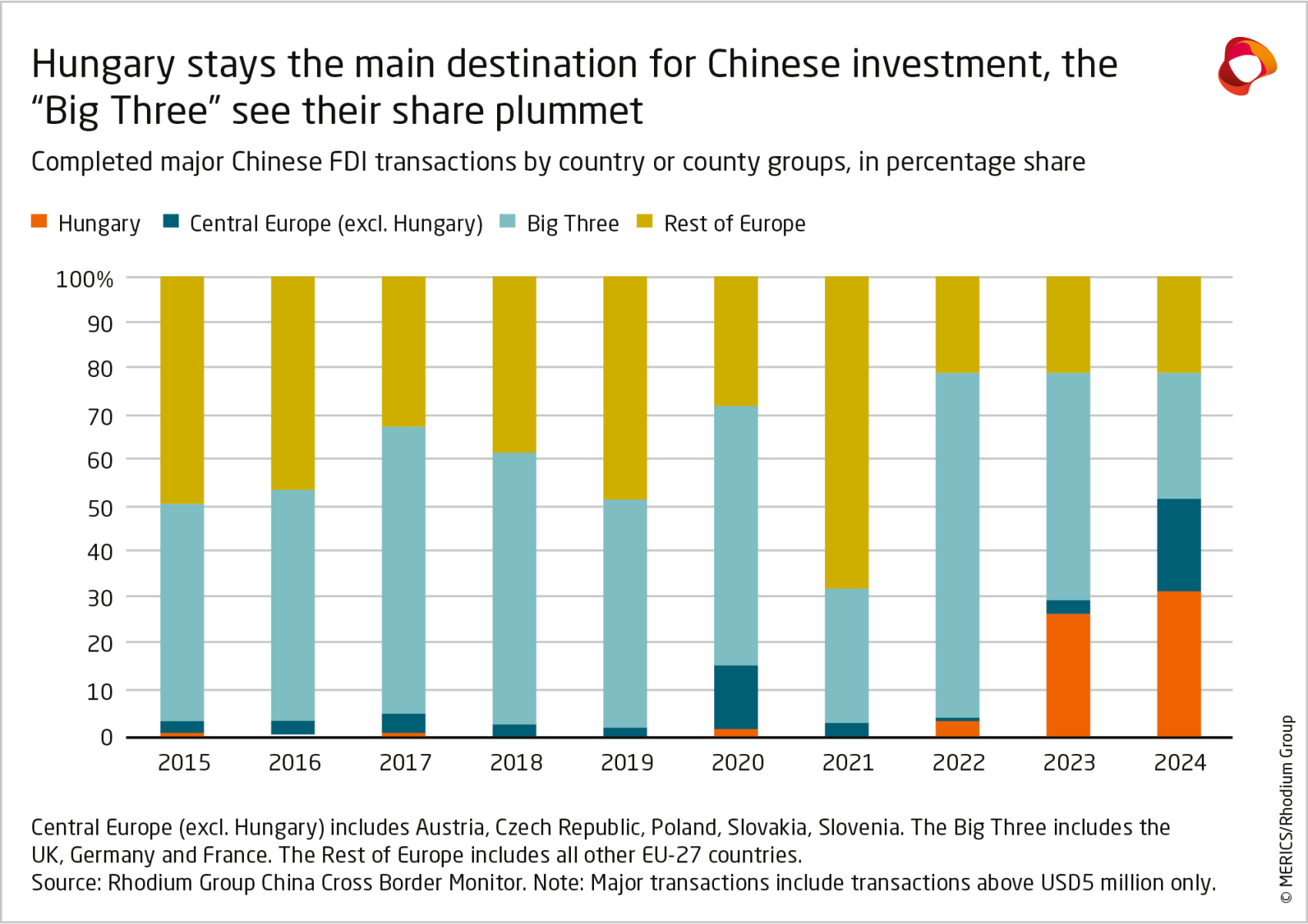

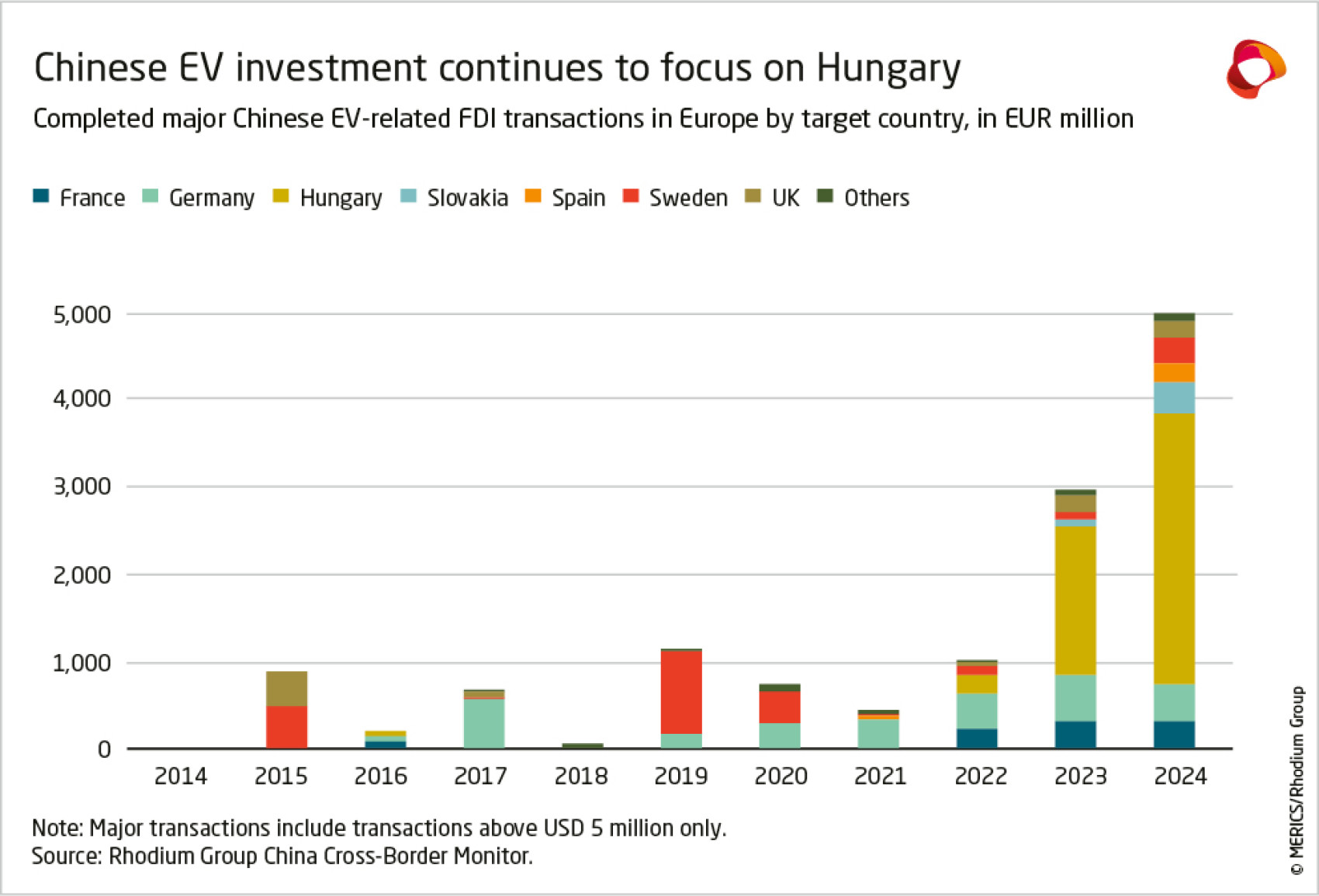

- Germany, France, and the UK lose ground as Hungary again takes the top spot: The combined share of the “Big Three”—the United Kingdom, Germany, and France—dropped to just 20 percent, sharply down from the 2019–2023 average of 52 percent. The decrease reflects both shifting investment patterns and a significant fall in overall investment. In contrast, Hungary—buoyed by capital-intensive greenfield projects—accounted for 31 percent of all Chinese FDI in Europe – the highest share of any country.

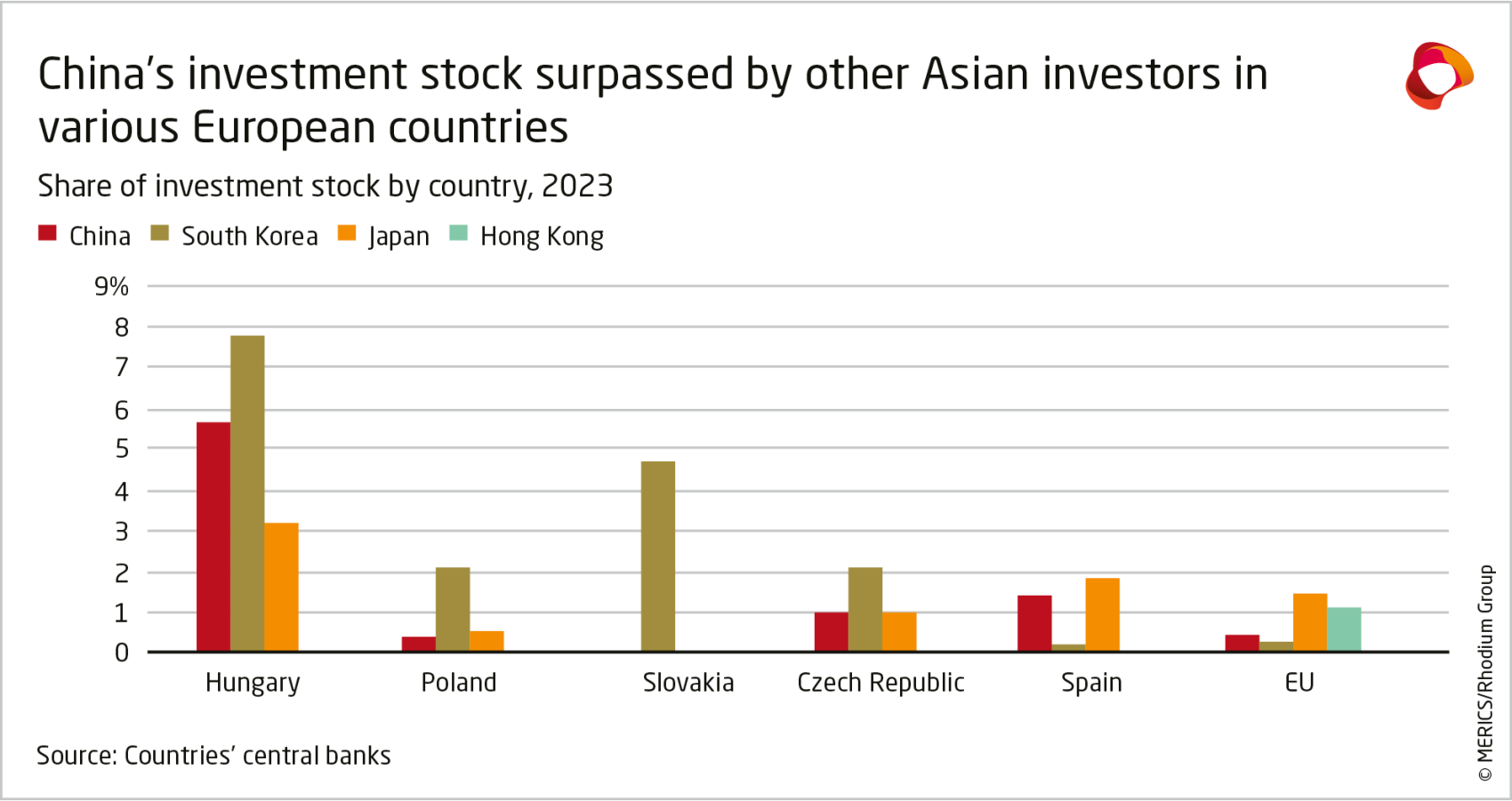

- China’s investment footprint in Europe remains limited: New Chinese greenfield EV investments in Europe have drawn attention, but the total stock of China’s EV FDI remains negligible compared to overall FDI stock in Europe, Europe’s FDI stock in China, and the scale of the EU-China trading relationship. While China is emerging as a lead investor in certain countries like Hungary, EU, US and South Korean partners are still ahead.

- A further increase is possible in 2025, but slowing EV FDI momentum puts the longer-term outlook for Chinese investment into question: A few large M&A transactions in 2025 could lead to another rebound, and greenfield FDI will hold steady with two EV battery plants confirmed to break ground in 2025. However, a sharp drop in the value of newly announced Chinese EV projects in 2024, as well as the cancellation of three major EV battery projects last year, raise questions about whether the increase in Chinese FDI in Europe can be sustained, with no other sector poised to offset a possible decline in EV investment.

1. Chinese investment in Europe rises for the first time since 2016

1.1 The rebound in Europe is part of a global recovery in Chinese investment

Chinese global outbound FDI rose for the first time in 2024 after seven consecutive years of decline, reaching EUR 52 billion according to Rhodium Group’s China Cross-Border Monitor1 (CBM) database.2 Chinese firms’ growing appetite for capital-intensive overseas greenfield projects drove the renewed momentum, despite a volatile investment landscape. The uptick also reflects attempts to circumvent rising trade barriers abroad, pressure to diversify supply chains, and the increasing global competitiveness of Chinese firms in advanced industries like clean technologies.

Geographically, Chinese FDI is weighted more heavily toward emerging markets (64 percent), particularly in Asia (32 percent). But for Chinese investment in high-income economies, Europe remained the key investment destination, capturing EUR 10 billion or 53.2 percent of these flows. The EU and the UK’s share of total Chinese FDI also rebounded to 19.1 percent in 2024, the first notable increase since 2018. This was better than its decade-low share of 15.4 percent in 2023. By contrast, investments in the United States continued falling, attracting less than EUR 2 billion in 2024 (or 4 percent of global Chinese outbound FDI).

1.2 Chinese investment in Europe rebounds in 2024 after a seven-year slump

Chinese companies invested EUR 10 billion in the EU and the UK in 2024, 47 percent more than the year before. This represents only one fifth of the 2016 peak but is nonetheless the first significant rebound in Chinese investment in Europe since 2016.

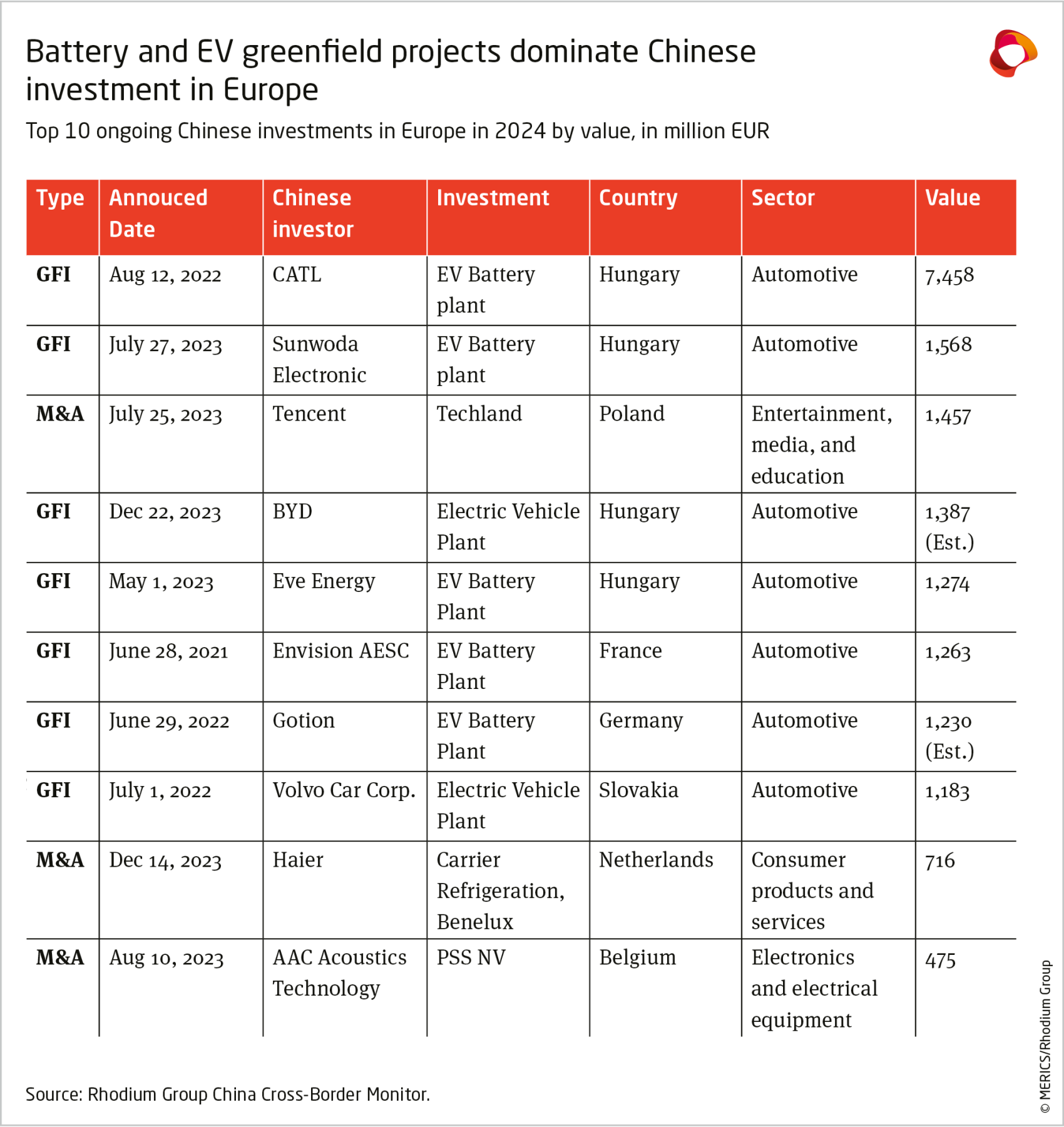

The rebound was driven by a slight recovery in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity and continued appetite for greenfield investment. After falling to its lowest level since 2009 in 2023, M&A investment more than doubled in 2024 to EUR 4.1 billion. However, this only put it on par with 2022 levels, which were already the lowest since 2010. The new momentum came from several large acquisitions, including three major transactions that accounted for nearly two thirds of total M&A FDI: Tencent’s purchase of Polish videogame developer Techland (EUR 1.5 billion), Haier’s takeover of Carrier’s Netherlands-based commercial refrigeration business segment (EUR 716 million), and AAC Acoustics Technology’s acquisition of the Belgian company PSS NV (EUR 475 million).

Greenfield investment also increased for the third year in a row (up by 21 percent year-on-year) and reached a new all-time high of EUR 5.9 billion. Greenfield projects made up the bulk (59 percent) of Chinese investment in Europe in 2024. EV-related projects continued to dominate, pulling in EUR 4.9 billion, or 83 percent of all Chinese greenfield FDI in 2024 (see exhibit 2). This ratio has been rising steadily over recent years, from just 17 percent in 2021.

China’s FDI rebound in Europe happened against a complex economic and geopolitical background. Chinese firms faced weak GDP growth, rising overcapacity, and fierce market competition at home, pushing them to seek opportunities abroad, either through exports or outbound investment. Internationally, growing trade tensions incentivized Chinese firms to expand their footprint overseas to avoid tariffs and other market barriers. But new investment from Chinese companies also triggered pushback. Europe is tightening regulatory scrutiny and the debate around conditioning or screening new Chinese greenfield projects is intensifying. There are also growing concerns in Beijing about technology transfer, and a desire to safeguard Chinese know-how—on top of the already extensive strict capital controls in place (we dive into these issues later on in the report).

1.3 Hungary remains top destination in 2024

Hungary maintained its role as the top destination for Chinese investment in Europe for the second year in a row thanks to large-scale EV projects. Hungary attracted Chinese investments worth EUR 3.1 billion in 2024, up 73 percent from EUR 1.8 billion the previous year. In 2024, four of the top 10 ongoing Chinese investments in Europe were located in Hungary, including three EV battery plants and one electric vehicle plant.

While the “Big Three” – the United Kingdom, Germany, and France – still hold the largest aggregate investment stock, recent shifts are affecting the geography of China’s European investment footprint. Hungary accounted for 31 percent of Chinese investments in Europe in 2024, while the combined share held by the “Big Three” was just 20 percent (see exhibit 4), a significant decline from an average of 52 percent between 2019 and 2023.

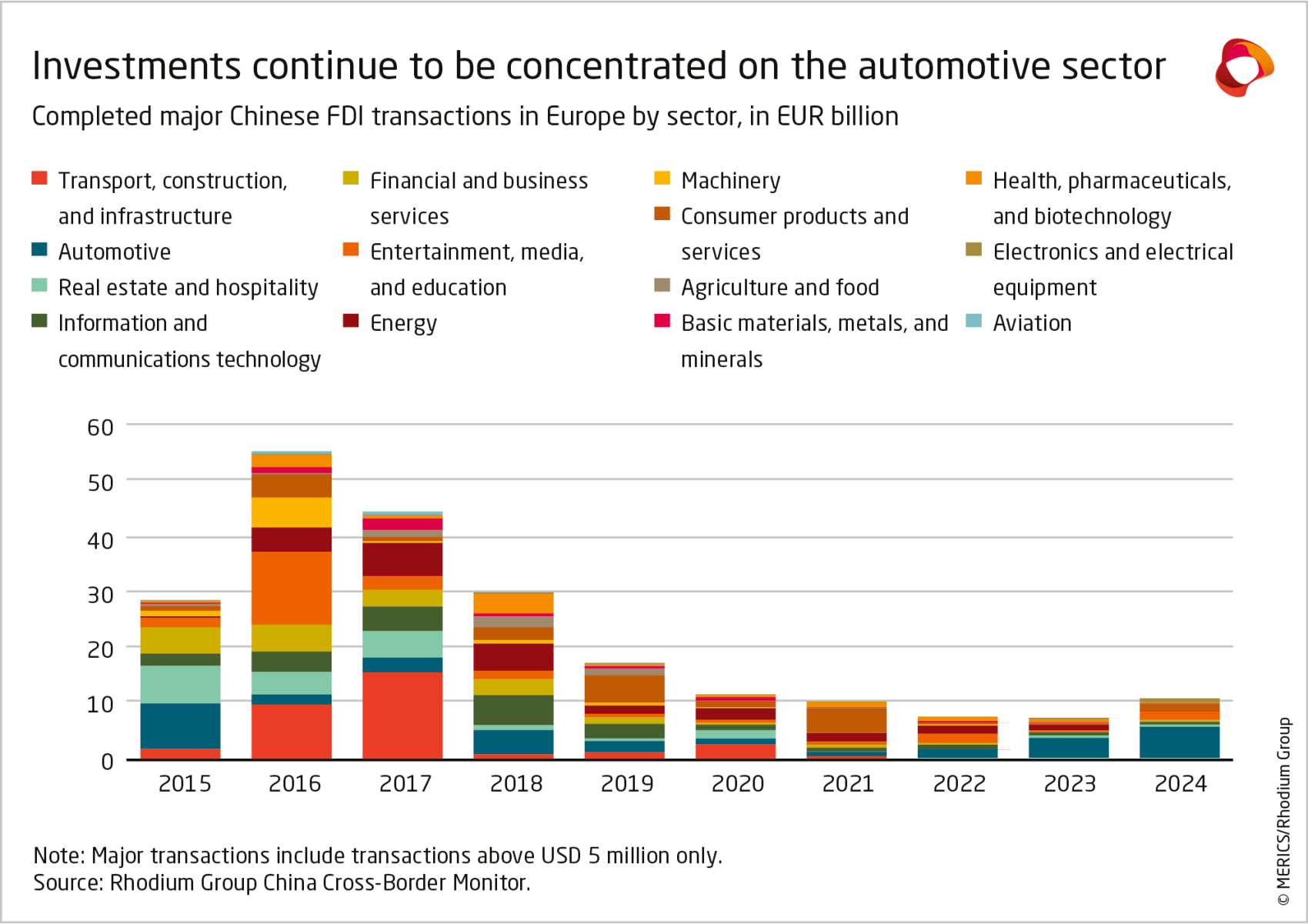

1.4 The automotive sector and EV projects continue to dominate Chinese investments

Chinese investment in the European automotive sector, by now overwhelmingly dominated by greenfield investments in EV-related sub-sectors, continued to drive most Chinese FDI in Europe in 2024 (see exhibit 5). It attracted EUR 5.2 billion in 2024, 57 percent more than the year before. These auto investments represented more than half of total Chinese investment in 2024. Seven of the top 10 Chinese FDI transactions in Europe in 2024 were related to EVs. Some of these are ongoing projects, such as CATL’s EV battery plant in Hungary (EUR 1.6 billion) and Envision AESC’s EV battery plant in France (EUR 1.4 billion). But new projects also contributed, including BYD’s EV plant in Hungary, estimated at EUR 1.4 billion.

Geographically, Chinese EV investments in Europe remain highly concentrated (see exhibit 6), with Hungary attracting 62 percent in 2024, up from 57 percent in 2023. Large investments included Sunwoda Electronic’s and Eve Energy’s EV battery plants, in addition to mega-projects mentioned above. Germany and Slovakia were the second and third largest destinations for China’s auto investments in 2024, making up 8 percent and 7 percent respectively. Key projects were Gotion’s EV battery plant in Germany, and Volvo’s EV plant in Slovakia.

Despite a flurry of ongoing projects, 2024 saw a 79 percent plunge in newly announced Chinese EV projects, down from EUR 15 billion on average in 2022 and 2023 to just EUR 3.1 billion. 2024 also witnessed several EV project cancellations. For instance, Svolt Energy confirmed the cancellation of its two battery plants in Germany worth a total of about EUR 4.2 billion.3 Nuode also suspended the construction in Belgium of a EUR 500 million battery component plant. Both cited financial difficulties and global market uncertainty. Meanwhile, Swedish authorities blocked Putailai’s planned construction of a EUR 1.2 billion anode plant due to unmet regulatory conditions that included management structure.

The level of investment in the automotive industry is expected to remain somewhat stable in the coming years, given long investment horizons and a few large projects still moving forward, including CALB’s EUR 2 billion battery plant in Portugal. That said, the attractiveness of localized production could diminish on the back of lower-than-expected demand for EVs in Europe, greater conditions applied to Chinese greenfield FDI, and growing incentives for Chinese battery firms to ship their products to Europe rather than make them on the ground.

There is no clear replacement industry for when the ongoing automotive projects lose steam. In 2024, the second most important sector for Chinese FDI was the entertainment, media, and education sector, attracting EUR 1.5 billion or 15 percent of Chinese investment. The consumer products and services sector was third, with EUR 1 billion or 10 percent of Chinese investments. However, investment in both sectors was characterized by just a few large M&A transactions, such as Tencent’s purchase of Techland (EUR 1.5 billion) and Haier’s takeover of Carrier’s Dutch refrigeration business division (EUR 716 million).

The only sector outside automotives to attract a sizeable amount of Chinese greenfield investment in 2024 was information and communications technology (EUR 457 million). Major projects included Nexperia’s EUR 185 million expansion of its main production site in Hamburg in Germany and Okmetic’s construction of a EUR 400 million silicon wafer production facility in Finland.

Looking ahead, the renewable energy sector may emerge as a promising new frontier for Chinese FDI—particularly in wind and hydrogen. In 2024, a dozen manufacturing and power generation projects were announced, most of them relatively modest, except for Envision’s EUR 900 million electrolyzers plant in Spain. As these projects have not yet broken ground, they are not reflected in our figures for 2024.

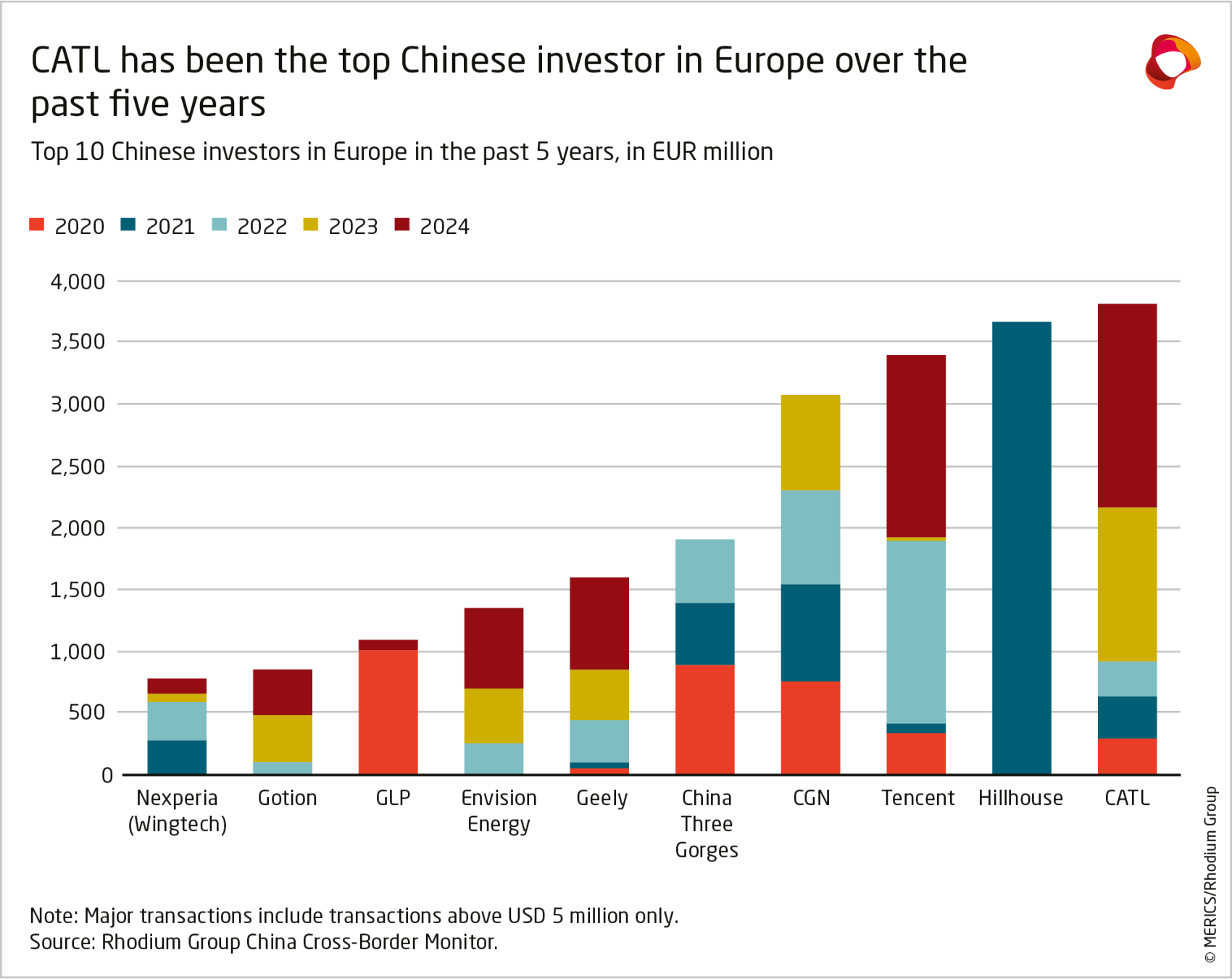

1.5 Chinese investment remains largely driven by a few firms

In 2024, a small group of highly active firms drove Chinese FDI into Europe. The top five investors—CATL, Tencent, Geely, Envision, and Gotion—accounted for almost half of total investments, a big jump from 35 percent on average the previous five years. CATL emerged as the leading investor in 2024, accounting for 16 percent of total investment, mostly from the ongoing construction of its battery plant in Hungary. This growing concentration reflects a broader trend: While fewer Chinese firms are investing in Europe, those that remain are scaling up significantly. Battery manufacturers such as CATL, Gotion, Envision, and Geely are rapidly expanding their production footprint across Western and Central Europe, with multiple gigafactory projects underway. Tencent, a leading Chinese M&A player in Europe, is accelerating its multibillion-euro acquisition spree in the video game sector. After two major transactions in recent years, Tencent is now planning a third for 2025—a EUR 1.1 billion acquisition of mobile game developer Easybrain. Over the past five years, Tencent has accounted for 8 percent of total Chinese FDI in Europe, just behind CATL’s 9 percent.

2. In-focus: The politics of Chinese EV greenfield FDI in Europe

China’s greenfield EV investments in Europe, now the main channel for Chinese FDI in the EU and the UK, have become more politicized in 2024. Many member states, facing challenging domestic economic conditions, have been eager to attract Chinese investment. China’s leadership has used investment prospects to seek to sway member states over key items of the EU-China relationship, including last year’s vote over EU’s EV duties.4 As transatlantic and US-China ties sour, Beijing’s efforts to sway Europeans may strengthen, including through the use of promised investment.

In this context, we seek to offer data on key questions for European policymakers at this juncture: How important is Chinese EV FDI in Europe in comparison to other EV FDI sources? Are Chinese companies picking certain countries out of commercial or political motivations? And how much local value added are China’s greenfield projects really contributing?

2.1 China’s investment footprint in Europe remains relatively small according to official FDI statistics

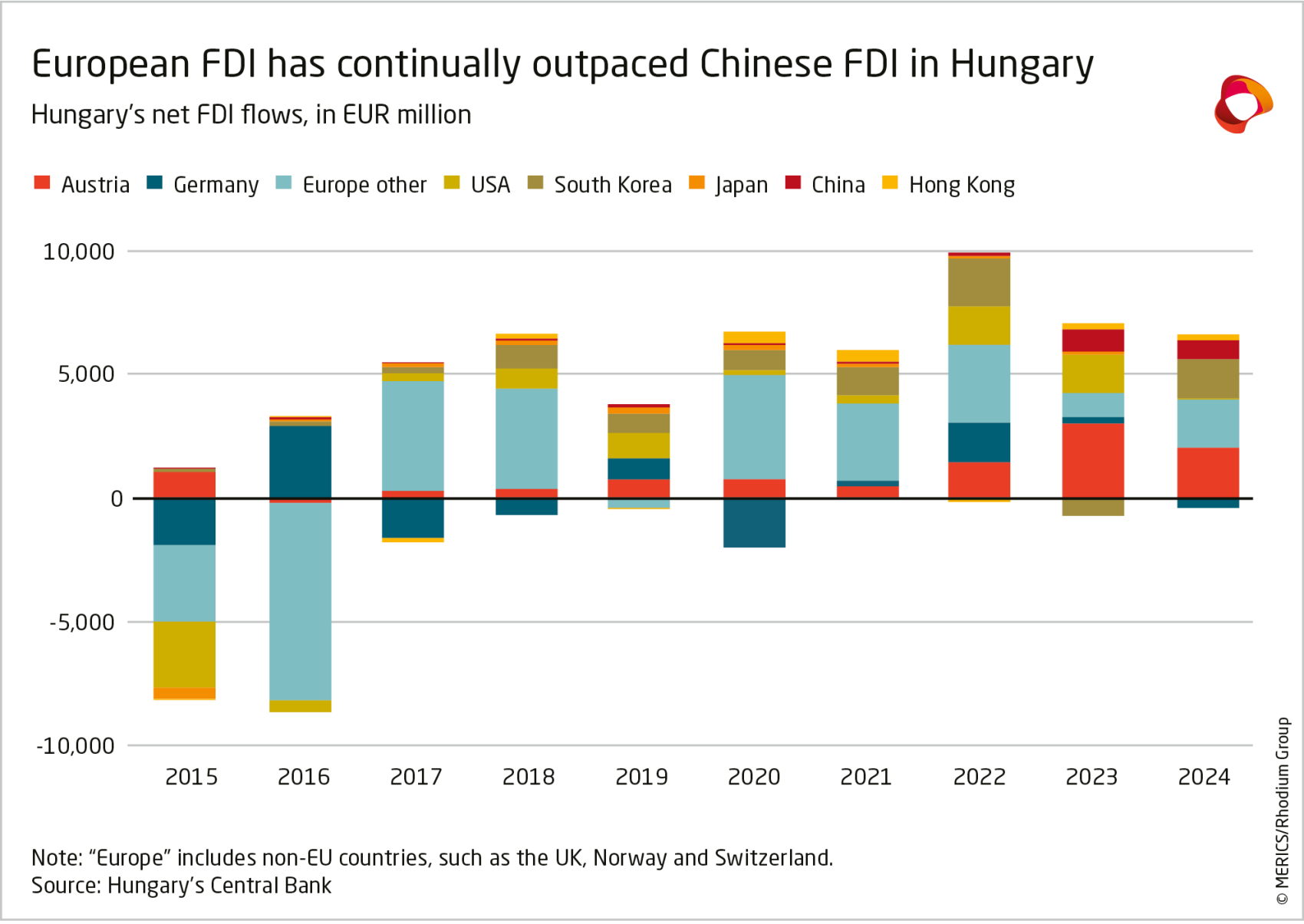

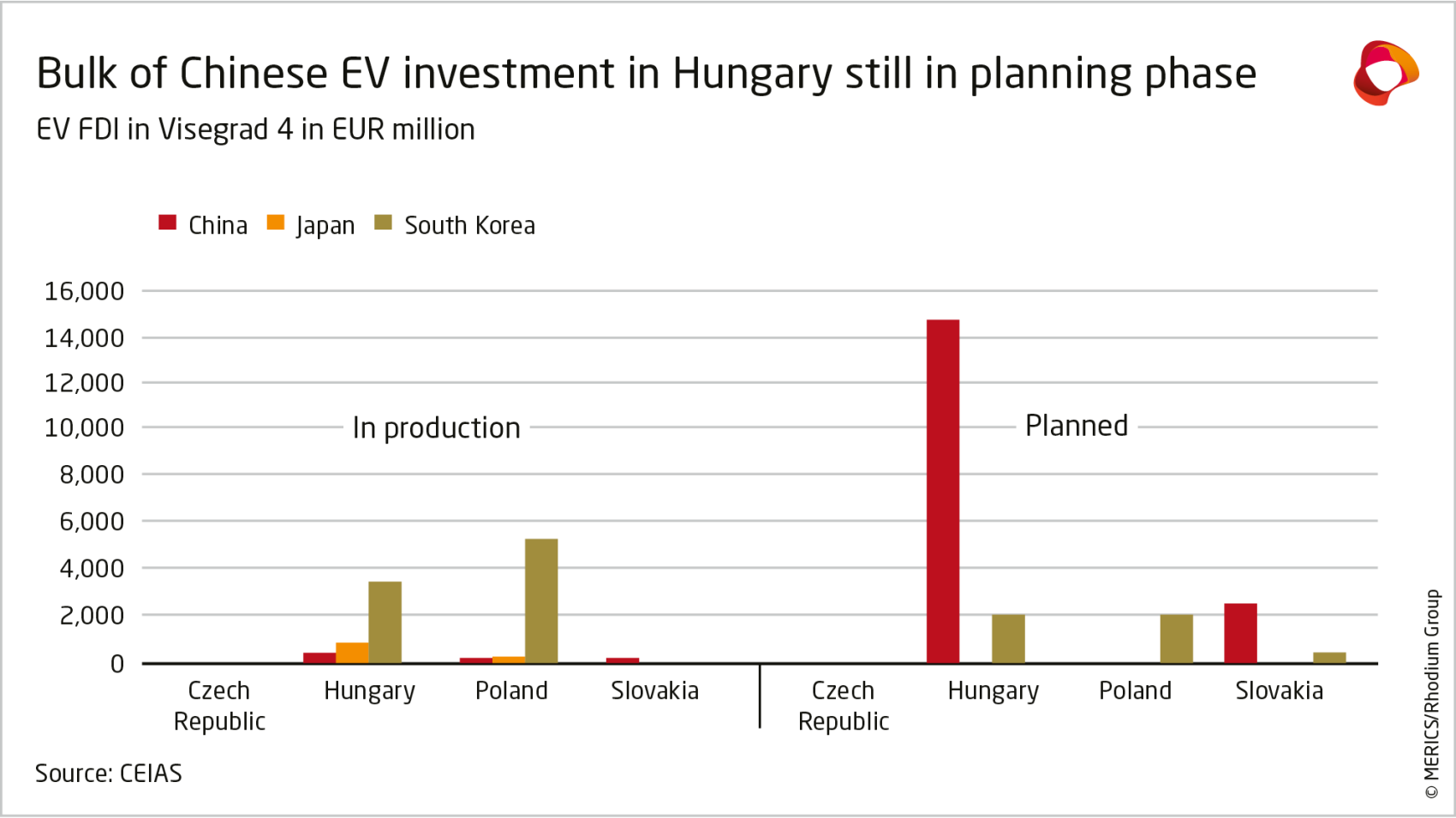

China today remains a relatively small investor in the EU, overshadowed by intra-European investments, as well as FDI from the United States and Japan (see exhibit 8). Even in Visegrád countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) and Spain, where China’s investment has concentrated in recent years given the strength of local automotive supply chains, investment stocks from South Korea and Japan outstrip Chinese FDI. South Korea stands out as the dominant Asian investor in Central Europe, thanks to the presence of major battery producers such as LG, SK, and Samsung and automakers Hyundai and Kia. In Hungary, which attracted the lion’s share of Chinese FDI in Europe the past three years, China’s overall footprint is growing but still somewhat limited compared to other partners.

In terms of FDI stocks, China only ranks sixth among Hungary’s foreign investors, behind Germany, Austria, the United States, South Korea, and France. If Hong Kong is included, China moves up to fifth place, accounting for 5.6 percent of Hungary’s total FDI stock in 2023. In terms of flows, Chinese FDI (including from Hong Kong) accounted for 18.6 percent of Hungary’s net inbound FDI in 2024, but Chinese investors were still third to European as well as South Korean investors (also in the EV sector, yet with considerably less political fanfare). Cumulative US FDI the past three years also exceeded Chinese FDI in Hungary.

This is not to say China is not gaining ground in select member states. Official data often comes with caveats, especially as regards Chinese FDI flows,5 and a closer look at announced EV-related FDI across the Visegrád countries shows much Chinese investment in Hungary is still in the planning or construction phase and so may not be fully captured by Hungary’s Central Bank data. This includes two flagship projects: BYD’s planned multibillion euro passenger car plant and CATL’s EUR 7.3 billion battery gigafactory. We therefore expect China’s FDI stock to grow in the years to come. These mega-investments also anchor a growing upstream supply chain, attracting Chinese component makers like Kedali (battery casings), Huayou Cobalt (cathodes), and Semcorp (separator films), as well as Western firms such as Forvia.

2.2 Local spillovers from China FDI

Greenfield investment is usually viewed in a positive light due to associated local benefits from job creation, knowledge transfer, and broader economic growth. Yet Brussels and several European capitals have become concerned that Chinese EV investments may primarily consist of mere assembly operations aimed at circumventing trade barriers, and/or producing limited local value add.

At this stage, most Chinese EV investments in Europe are still in early development phases, making it hard to gauge their long-term impact. For instance, BYD’s passenger car plant in Hungary is scheduled to begin production in late 2025. So far, localization seems limited. Reports suggest BYD is importing even the steel to construct its new Hungary plant and intends to continue importing battery cells—one of the most value-intensive EV components—from China. BYD executive Stella Li has said only that the company may consider EU-based battery production in the future.6

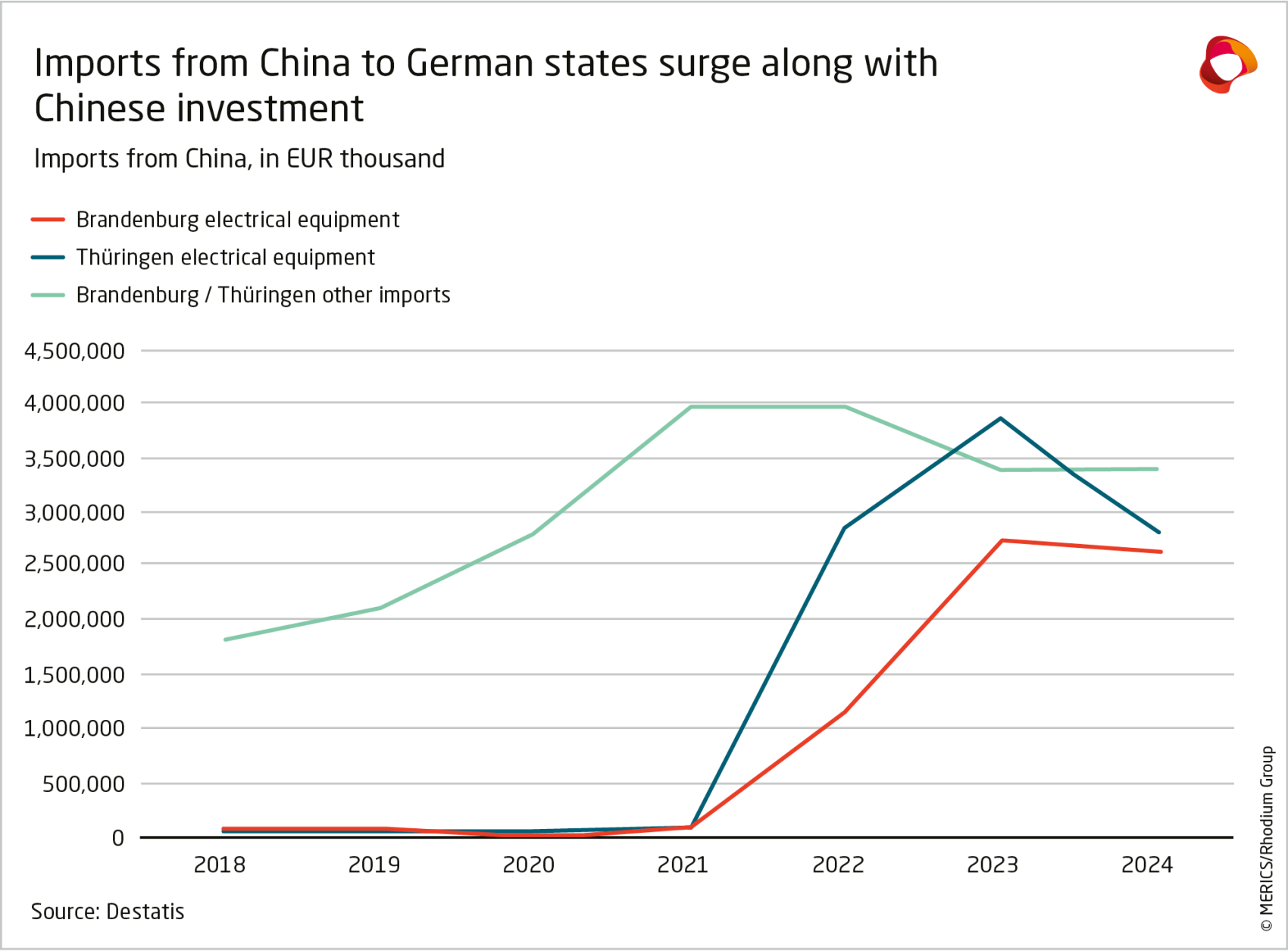

Beyond BYD, there are also signs that Chinese investment, and foreign investment more generally, tend to rely primarily on imports during their operations’ early stages. This is visible in the sharp rise in imports of electrical equipment from China into German states like Thuringia, where CATL began building a battery plant in 2019 and launched operations in 2023. But these trends can also be observed in Brandenburg, where Tesla’s Gigafactory broke ground in 2020 and began production in 2022.

Yet this early-stage dependency on foreign inputs might come down over time. BYD’s electric bus plant in Komárom, operational since 2017, initially sourced around 20 percent of its components from European suppliers, but that number then rose to 30–50 percent by 2019. Roughly 90 percent of the 260-person workforce were Hungarian locals, with a small number of PRC managers and short-term staff.7

For its EV plant, BYD has already signed supply agreements with at least five European firms, including Brembo8 and Forvia9—both of which have partnerships with BYD in China. BYD also held supplier conferences in Austria, Hungary, and Italy, collectively involving several hundred potential partners.

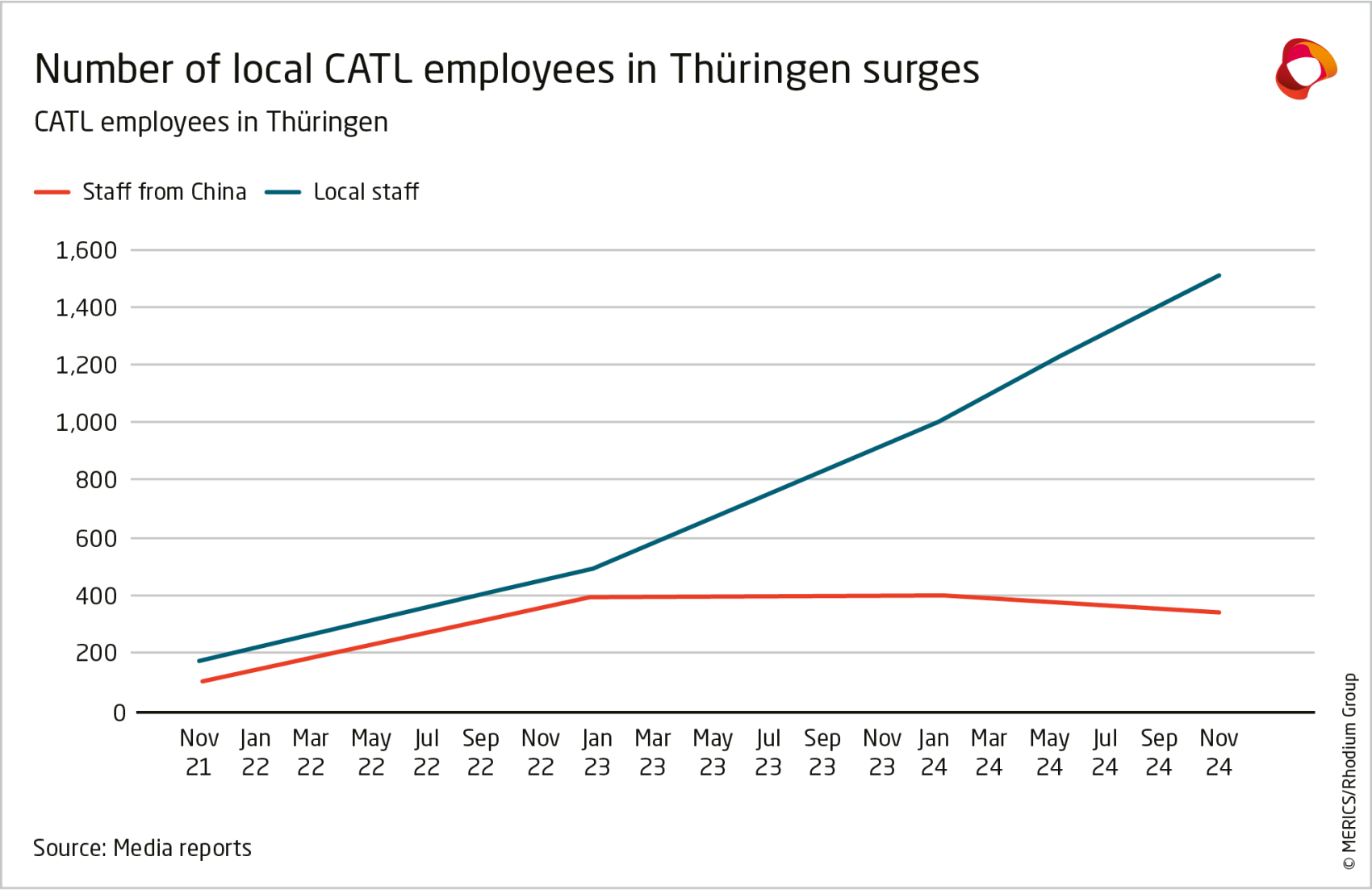

A few other case studies point to local value add increasing over time. When CATL began ramping up production at its German plant, PRC staff initially made up nearly half of the workforce, to provide technical expertise to set up production lines and train local staff on complex machinery and processes. But by late 2024, these made up only 23 percent of the workforce and their absolute numbers seem to have peaked in 2022–2023. As operations stabilized, most new hires were local, reflecting a gradual shift toward workforce localization. CATL’s investment in Germany also generated secondary local activity. In 2021, KDL Germany—a subsidiary of Kedali Shenzhen Industry—announced a EUR 60 million investment to produce aluminum castings for CATL batteries, with plans to create up to 290 local jobs.10

In short, while the local value added of Chinese greenfield EV investments in Europe appears so far limited, this might reflect a broader trend in the auto sector rather than a uniquely Chinese challenge—particularly in the battery segment, where local supplier eco-systems and skilled labor remain underdeveloped. Evidence from a small number of case studies suggests that local content tends to increase over the medium term.

Still, current economic and political dynamics could affect the trajectory. Chinese authorities might encourage firms to retain higher value-added activities at home to support domestic jobs, industry and exports, especially given rising US tariffs. In contrast, European policymakers may seek to condition market access on greater local content. If such measures are well-targeted, they could accelerate value creation within Europe. If poorly designed, they may end up diverting FDI to other destinations (e.g. Turkey or Morocco) or deterring investment altogether by increasing operational costs beyond commercial viability.

2.3 Location decisions are shaped by a mix of political and commercial factors

Various European governments—such as France and Italy—have actively welcomed Chinese EV investment. In 2024, then French economy and finance minister Bruno Le Maire publicly urged BYD to invest in France. However, Chinese EV-related FDI has been largely concentrated in Hungary and, increasingly, in Slovakia and Spain. This has raised questions about whether Chinese EV investment decisions in Europe are based more on political or commercial considerations. Hungary and Slovakia, after all, opposed the EU’s EV duties, and Spain switched its vote from support to abstention after Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez visited Beijing. By contrast, Italy and France have been persistent supporters of the EU’s EV investigation. The reality is more complex, however, as Chinese FDI decisions in Europe respond to a combination of commercial, political, and structural factors.

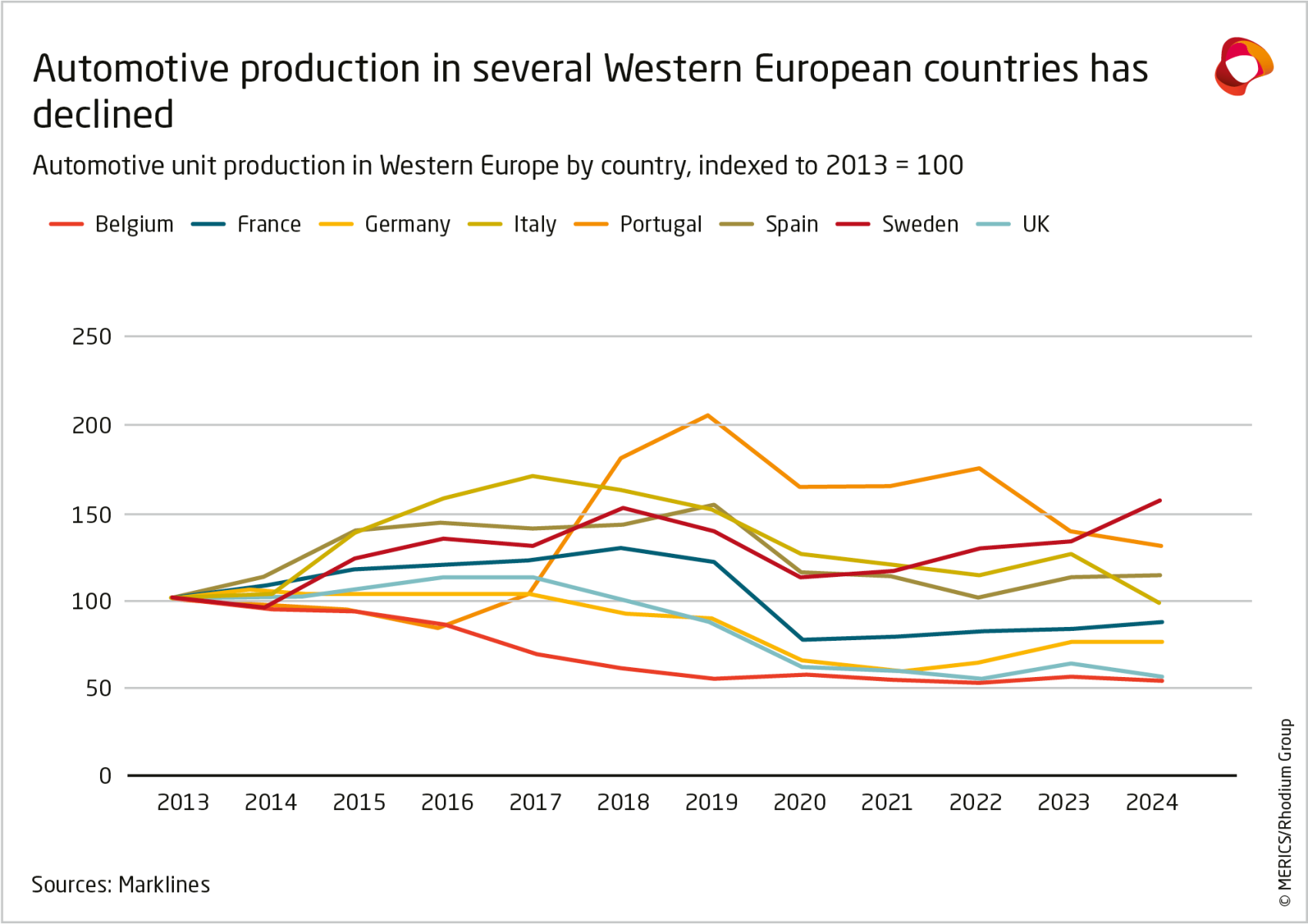

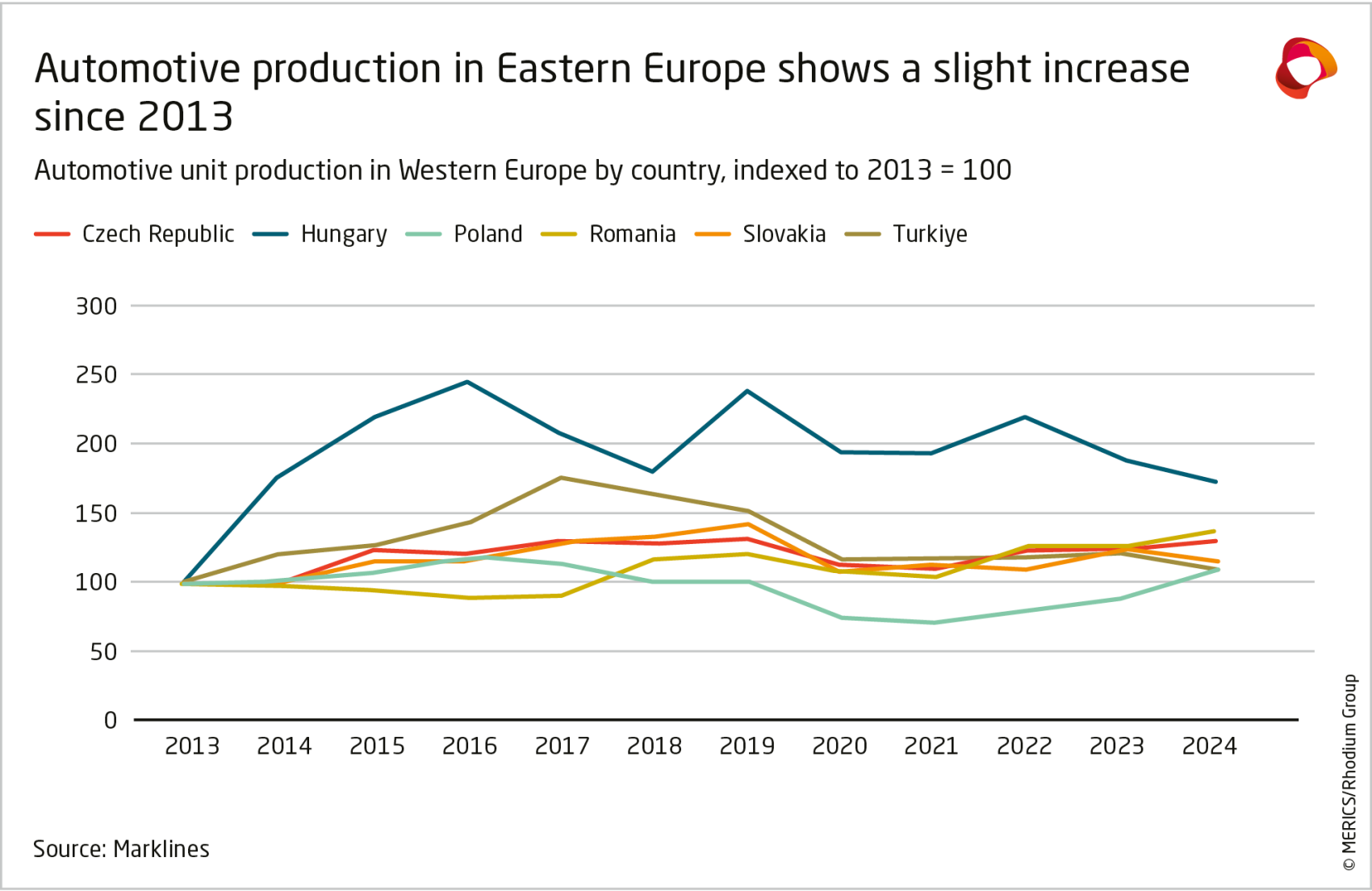

For one, traditional automotive hubs—Germany, France, the UK, and Italy—are seeing manufacturing decline as both Western and Chinese automakers shift production to lower-cost locations in Eastern Europe, North Africa, or (to a lesser extent) the Iberian peninsula. High energy and labor costs, along with western Europe’s stricter regulatory frameworks, are pushing auto firms to reconfigure their investment strategies. It would be counterintuitive in this context for Chinese EV firms to prioritize Germany or France over southern or eastern European destinations, unless for political reasons. Although Germany and France have deep talent pools and strong R&D ecosystems, the commercial case increasingly favors alternative destinations.

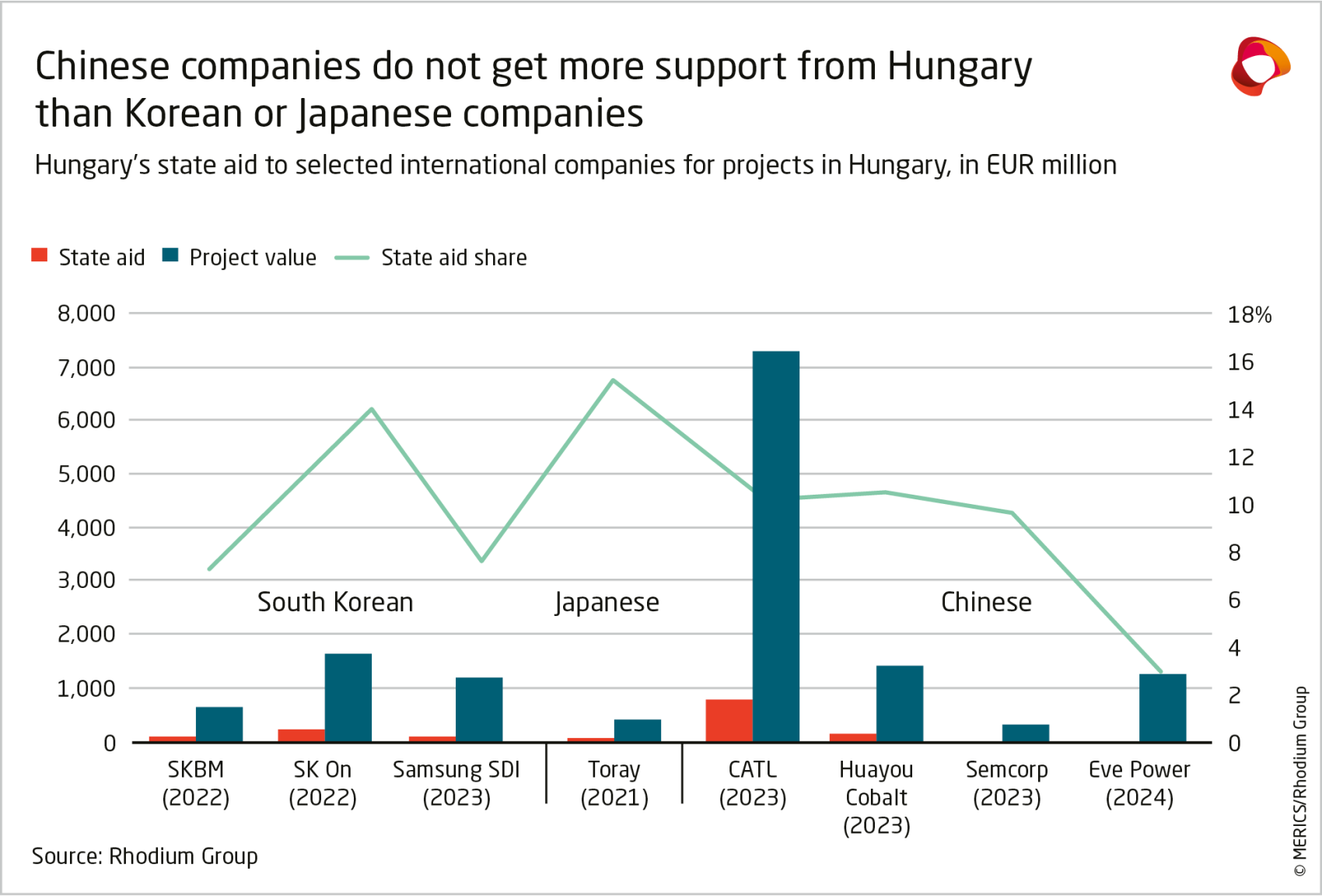

Hungary has also been handing out generous state support packages and may, though difficult to verify, impose fewer conditions linked to technology transfer, local workforce development or local content. By contrast, Rome tried to negotiate local content requirements with Dongfeng, a Chinese state-owned carmaker, including at least 45 percent of all components sourced in Italy data stored locally, in exchange for state aid. While Chinese firms do not seem to receive more support than Korean or Japan ones,11 Hungary probably benefits from the combination of state aid and limited conditions imposed on investors.

In short, there is a strong commercial motive for investments in Hungary and Spain. The main question then is why countries like Poland—also an automotive hub and recipient of significant South Korean EV investment—do not attract more Chinese FDI. This is where political factors may come into play. Since early October 2024, when member states voted on EV duties, Chinese government pressure seems to have tempered Chinese firms’ appetitive for new investments.12 New announcements have tended to favor countries that opposed or abstained from the duties—such as Kunlun Chemical in Hungary. Political factors may also have played a role in the decision by Leapmotor and Stellantis to build the Leapmotor C10 in Spain, rather than Poland. After all, although Poland signaled interest in EV collaboration during President Duda’s visit to China, it still voted for EU anti-subsidy duties on Chinese EVs.

But there are also exceptions. After the EV vote, Ningbo Ronbay announced plans to acquire a cathode materials facility in Poland after Johnson Matthey exited its battery materials business. And while Germany opposed the EU’s EV duties in the crucial October vote, it has received the least Chinese FDI in 2024 in fifteen years and seen projects cancelled in favor of more cost-competitive destinations (Spain and Portugal).

3. Regulatory developments: Europe expands its approach to reviewing Chinese investments

Europe has grown increasingly sensitive to the potential risks presented by Chinese investments. This has come alongside rising concerns about the security of critical infrastructure, supply chains, technology transfer in critical and dual-use fields, and level playing field issues related to China.

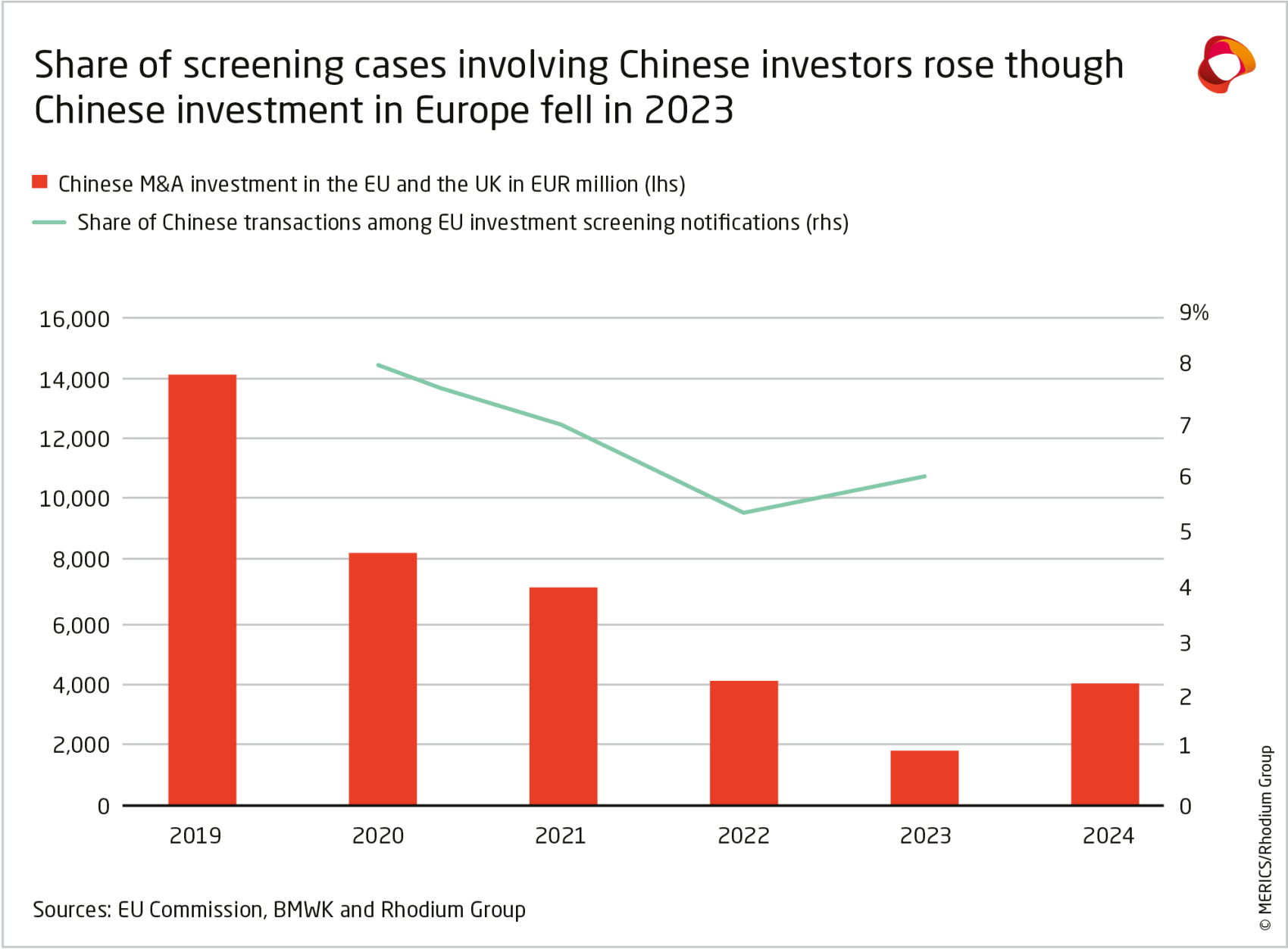

These concerns are reflected in recent trends in European reviews of Chinese FDI. According to the EU’s latest yearly investment screening report (covering 2023), the share of screened transactions involving Chinese companies rose for the first time in years—to 6 percent in 2023, up from 5.4 percent in 2022.13 This was despite Chinese FDI to Europe dropping from 2022 to 2023, especially via M&A transactions.

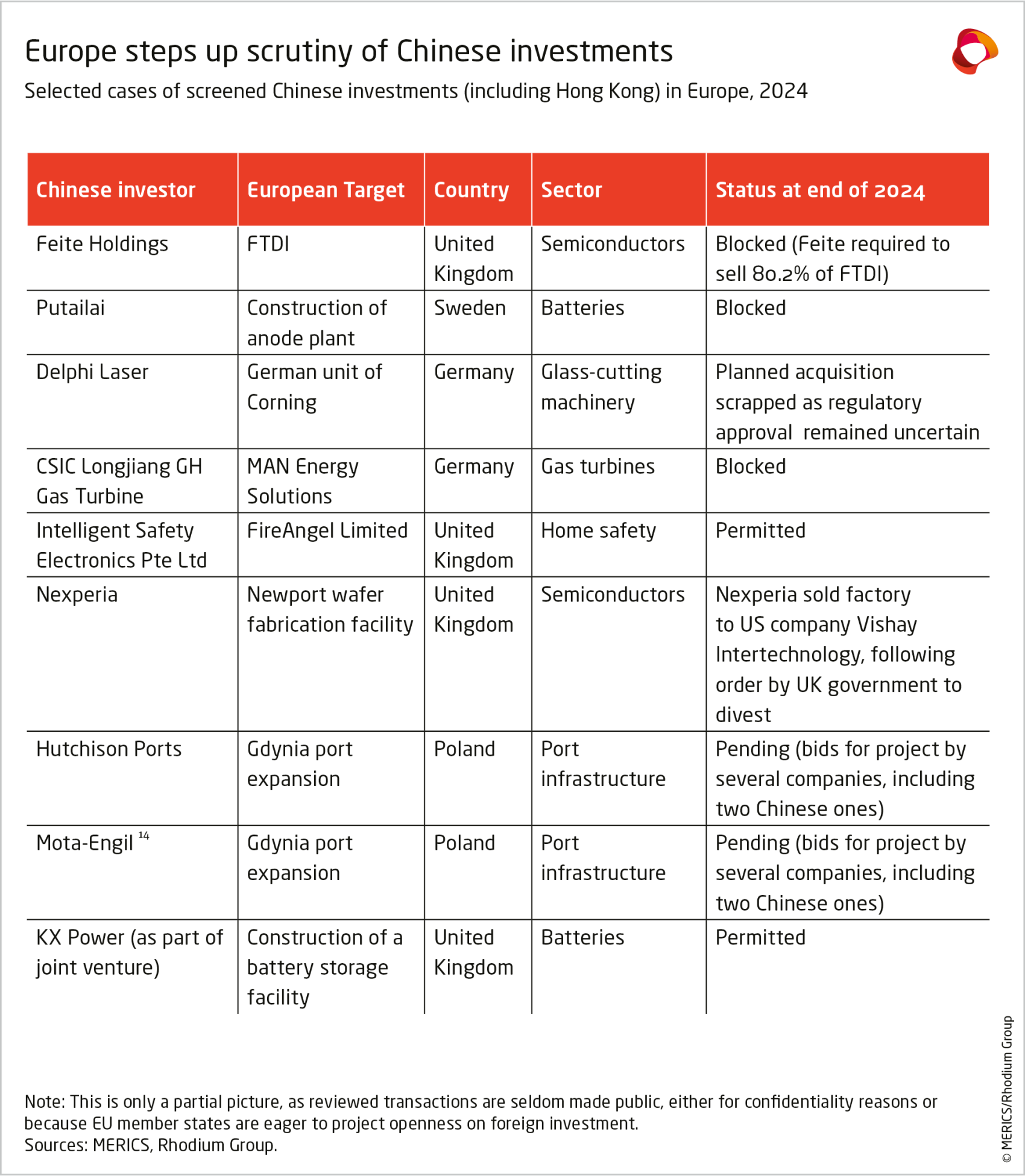

We found Chinese companies were involved in nine publicly disclosed investment screening cases in 2024, meaning either a screening review was launched or a decision was made. This was fewer than we found in 2023 (12) and 2022 (16), but may also reflect greater efforts to keep these cases confidential. Somewhat unsurprisingly, publicly disclosed reviews involved sectors with a national security dimension, including semiconductors, batteries, and gas turbines. Reviews of two semiconductor transactions concluded in divestments by Chinese firms, while in the battery sector, one transaction was blocked and another was permitted.

These reviews happened on the back of tightening screening mechanisms. As of February 2025, 24 countries of the EU-27 had investment screening mechanisms in place and the three members without a regime—Greece, Cyprus, and Croatia—were all reportedly working on setting one up.15, 16, 17 On a European level, the European Commission published a proposal to revise—and tighten—the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/452) in January 2024.18

The Commission proposal and the European Parliament’s negotiating draft19 are reflective of new debates around investment screening in Europe, especially with a focus on China. While the Parliament’s draft is broadly in line with the Commission’s, it goes further to propose granting the Commission authority to overrule member states’ FDI approval decisions on the grounds of threats to national security or public order. This would be a major change as at present FDI screening is strictly a member state competency, with the Commission’s role largely limited to offering opinions.

The draft also introduces the possibility of “conditioning FDI” via a range of mitigating measures to investment approvals in certain strategic sectors. The proposal reflects growing debates in Europe about the need to extract more benefits from the boom in greenfield Chinese FDI, including through greater requirements in terms of local value added, local content or skill and knowledge transfer (the later being especially important in fields where China leads globally, including EVs, batteries, and a range of other green technologies). Parliament’s proposed “mitigation measures” include:

- Requirements for the investor to maintain or create local added value;

- Prevention of unauthorized access to sensitive technologies or information;

- Investor commitments to address the risk of dependency, including the transfer of technologies and know-how; and

- Cybersecurity protocols to protect against potential threats as well as obligations to store and process specific data within the EU.

The Parliament’s proposals are likely to face strong pushback from the European Council, the third negotiating partner in this review process. The Council’s negotiating position reportedly pares down the Commission’s proposed list of technologies for mandatory investment screening (for example, removing semiconductors and AI).20 The Council is also likely to push back against the Parliament’s proposal to empower the Commission to overturn national level decisions on screening cases, and its desire to leverage the screening regulation to start conditioning Chinese FDI.

Yet if the Parliament’s proposals fail, policymakers in Brussels and European capitals might start considering other avenues to the same goals.21 This could include, for example, applying similar stipulations (on local hiring, local content and transfer of knowledge, and skills) to foreign companies receiving EU financial support or operating in publicly procured sectors.22

The Commission might also tighten its grip over Chinese FDI through other means. In recent years, the EU expanded the legal grounds for reviewing FDI to include competitive and subsidies concerns under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR). A few months back, the FT reported23 that Brussels was considering launching an FSR investigation into BYD’s EV plant in Hungary. This would mark the first ex officio use of the FSR in relation to greenfield investment.

Increasing, we might also see governments use various policy tools to “claw back” certain assets that have come under Chinese ownership. The UK recently rushed through legislation to authorize the government to direct the use of—or, as a last resort, nationalize—assets in the steel sector if a company is at risk of closing operations against the public interest.24 These emergency powers came as Chinese firm Jingye threatened to shut down British Steel’s plant in Scunthorpe, the country’s last remaining blast furnace.

Some companies finally may seek to distance themselves from their Chinese owners to mitigate political and regulatory pressures. Italian tire-maker Pirelli, for example, is reportedly locked in a boardroom battle to reduce majority shareholder Sinochem’s stake, amid concerns that Chinese ownership is blocking its investment plans in the US, crucial for the company to navigate the US’ new tariffs on auto parts.25

4. Outlook

The weakness in Chinese FDI in Europe in recent years stemmed from a dearth of Chinese M&A activity. Tight outbound investment controls and lesser financial capacity at Chinese firms put a cap on dealmaking, all while more tech and IP transfers started happening directly within China (rather than by buying European assets). Greater European scrutiny of Chinese investments might also have discouraged transactions in more sensitive sectors. While we do not expect a return to historic heights, 2024 data shows that a few large acquisitions can, at low current levels, create spikes in Chinese investment. We expect Chinese M&A investment in Europe to remain stable or rise modestly in 2025.

What’s more, ongoing projects will put a floor on greenfield FDI value for the next two-three years. While three multibillion EV battery plants were abandoned in 2024, two projects were confirmed and will start showing in our data from 2025. Current projects could also attract additional investment by Chinese suppliers looking to follow their Chinese clients overseas, especially as member states start demanding more local content from Chinese investors.26 In addition, Europe attracted a new wave of greenfield investment in clean tech sectors in 2024, including manufacturing and power generation, though these projects tend to be less capital intensive than the earlier surge in EV battery investments, in what would constitute a new emerging pattern, Chinese firms could finally seek to take over European plants from distressed owners.27

Against that backdrop, a few more factors will determine the trajectory of Chinese FDI in Europe this year:

China’s economic weakness and continued deflationary pressures will incentivize Chinese firms to look abroad. Europe faces low growth too, especially in its auto sector, but higher margins in the EU and UK will have a strong appeal to Chinese firms. Europe has one of the most open investment environments among developed economies and is a great sectoral fit with China’s overcapacities and priorities.

Whether Chinese companies internationalize through exports or FDI will depend on policies in China and Europe. New European policy documents that raise market barriers, including the Competitiveness Compass,28 the Clean Industrial Deal,29 and the Industrial Action Plan for the European automotive sector,30 could incentivize Chinese firms to take the FDI route. However, these trade barriers will need to be high enough to drive investment (otherwise the export route will remain preferable), yet not so burdensome (in raising input prices or requiring local content) as to negate the business case of manufacturing in Europe.31 If barriers go too high, certain Chinese firms might also start doubling down on alternative pathways, including licensing agreements and strategic partnerships—approaches that are not captured in traditional FDI statistics. Notable existing examples include Leapmotor’s collaboration with Stellantis in the automotive sector and the Huasun–Bee Solar partnership in photovoltaics.

European policymakers must walk this tightrope carefully. Many countries are seeking to attract FDI and Chinese firms confront hard choices between destinations. In the auto sector, for example, Chinese OEMs will be pressed to weigh the advantages of producing in Europe against those of Turkey or Thailand, including for re-export to the EU market.

US tariffs and attempts at dealmaking will complicate this picture, potentially pushing Chinese firms to favor the export route. If new US tariffs cause a large enough shock to China’s export sector, firms may choose to maximize usage of China-based production capacity, even if margins fall. China’s reaction to US measures, including allowing the CNY depreciate, will besides make outbound investment more expensive.

Security concerns will continue rising over connected technologies, from connected vehicles to wind equipment to medical devices. All are undergoing risk reviews under the EU’s NIS 2 directive. These concerns could especially put the brakes on Chinese firms’ expansion into renewable energy, a popular sector over for greenfield investment the past couple of years in southern Europe.

Finally, Chinese investment will be affected by the trajectory of EU-China relations. EU-China ties could improve momentarily amid the United States’ new trade war.32 With growing economic and geopolitical uncertainty, a more conciliatory approach towards Beijing may emerge. Some member states will urge Brussels to avoid a two-pronged trade war— and could be rewarded with further promises of Chinese FDI (EUR 4.2 billion in investment has been committed in Spain in 2024, more than in any EU country). Yet Brussels is also likely to response to structural and systemic production overcapacities in China with more defensive actions. By increasing the cost of imported goods, these measures could draw in Chinese FDI. Yet they will also increase the level of uncertainty for Chinese investors, especially if paired with reviews of Chinese FDI on competitive grounds. If Brussels’ investigation into BYD’s Hungary factory is confirmed, it could have a chilling effect on Chinese companies’ willingness to invest in Europe. So could the EU’s revision of its FDI screening regulation if it ends up conditioning Chinese inbound investment in strategic sectors. Finally, these measures could trigger strong counter-reactions from Beijing, including direct guidance to Chinese firms not to invest into certain European economies.

- Endnotes

2 | By capturing verified investment transactions, the CBM avoids the distortions common in official statistics and enables a granular breakdown of trends by destination, sector, and investment type, offering a more accurate view of Chinese outbound investments (https://cbm.rhg.com/methodology).

3 | Svolt Energy reportedly suspends 2 battery factory projects in Germany - CnEVPost

5 | Official FDI statistics are subject to well-documented distortions, which are particularly pronounced in the case of China due to the nature of its external economic configuration. Chinese investment flows are often routed through offshore jurisdictions such as Hong Kong or the Cayman Islands. In Europe, they are sometimes recorded under the jurisdiction of Chinese companies‘ regional subsidiaries—frequently located in the Netherlands or Germany in the case of EV investors—rather than being attributed directly to China.

6 | https://www.automobilwoche.de/autohersteller/vizechefin-stella-li-kundigt-drittes-byd-werk-europa

7 | https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13602381.2022.2093535

11 | While CATL’s EUR 800 million incentive package is the largest in absolute terms, the share of aid relative to the total investment is lower than that granted to South Korean or Japanese firms.

13 | 2023 is the latest year, for which investment screening data aggregated on a European level is available.

14 | China Communications Construction Co., Ltd. owns a 32 percent non-controlling stake.

15 | https://www.lloydsbanktrade.com/en/market-potential/greece/investment

16 | https://cyprus-mail.com/2024/11/04/calls-for-swift-passage-of-foreign-investment-screening-law/

19 | https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/INTA-PR-767951_EN.pdf

20 | https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-capitals-fdi-screening-rules-china/

22 | https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_636

23 | https://www.ft.com/content/0ef28741-6194-4ee6-8f23-945415de7458

28 | https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_339

29 | https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/clean-industrial-deal_en

31 | https://rhg.com/research/aint-no-duty-high-enough/

32 | https://rhg.com/research/trump-and-the-europe-us-china-triangle/

Building on a long-standing collaboration between Rhodium Group and MERICS,

this report summarizes China’s investment footprint in the EU-27 and the UK in

2024, analyzing the shifting patterns in China’s FDI, as well as policy developments

in Europe and China.