China’s overcapacity and the EU + German China policy under Merz + EU-China trade

Analysis

China’s overcapacity and the EU – All you need to know

By Esther Goreichy, Jacob Gunter and Grzegorz Stec

In its pursuit of self-reliance and technological security, Beijing’s economic model is generating intense overinvestment, overproduction, and overcapacity in its industrial base. Effectively, China is producing more and more goods across a range of industries while consumption fails to grow in any meaningful way. China now accounts for roughly one third of total global value-added manufacturing, and its trade surplus hit nearly USD 1 trillion last year. The resulting glut of supply is driving down prices globally as more and more China-made goods enter global markets.

The fierce price wars within China’s own market have driven down profitability, and nearly a quarter of its industrial enterprises are now loss-making. In a normal market economy, this would lead to consolidation as the least efficient players exited the market, and prices and profits stabilized. This is not happening at the pace necessary in China, largely due to China’s extensive industrial policy, massive subsidies, cheap financing, and other support measures.

The resulting waste and inefficiencies are tolerated ideologically under the current leadership, which views self-reliance and technological security as essential goals and the scale of its still-growing manufacturing base as one of China’s core geopolitical strengths. China’s overcapacity issue is troubling not because China is a net exporter, but because it is exporting market distortions that warp prices in market economies on an unsustainable scale.

This is deeply problematic for global markets, including in Europe. The European common market, with its robust competition law that binds companies by fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders, is simply not designed for competition with the firms emerging from China’s new economic model.

Which European sectors are particularly vulnerable?

China’s overcapacity issues are well established and have already impacted some traditional European industries like steel and aluminum. But the current wave is different in that it involves more value-added sectors, like passenger vehicles and EVs.

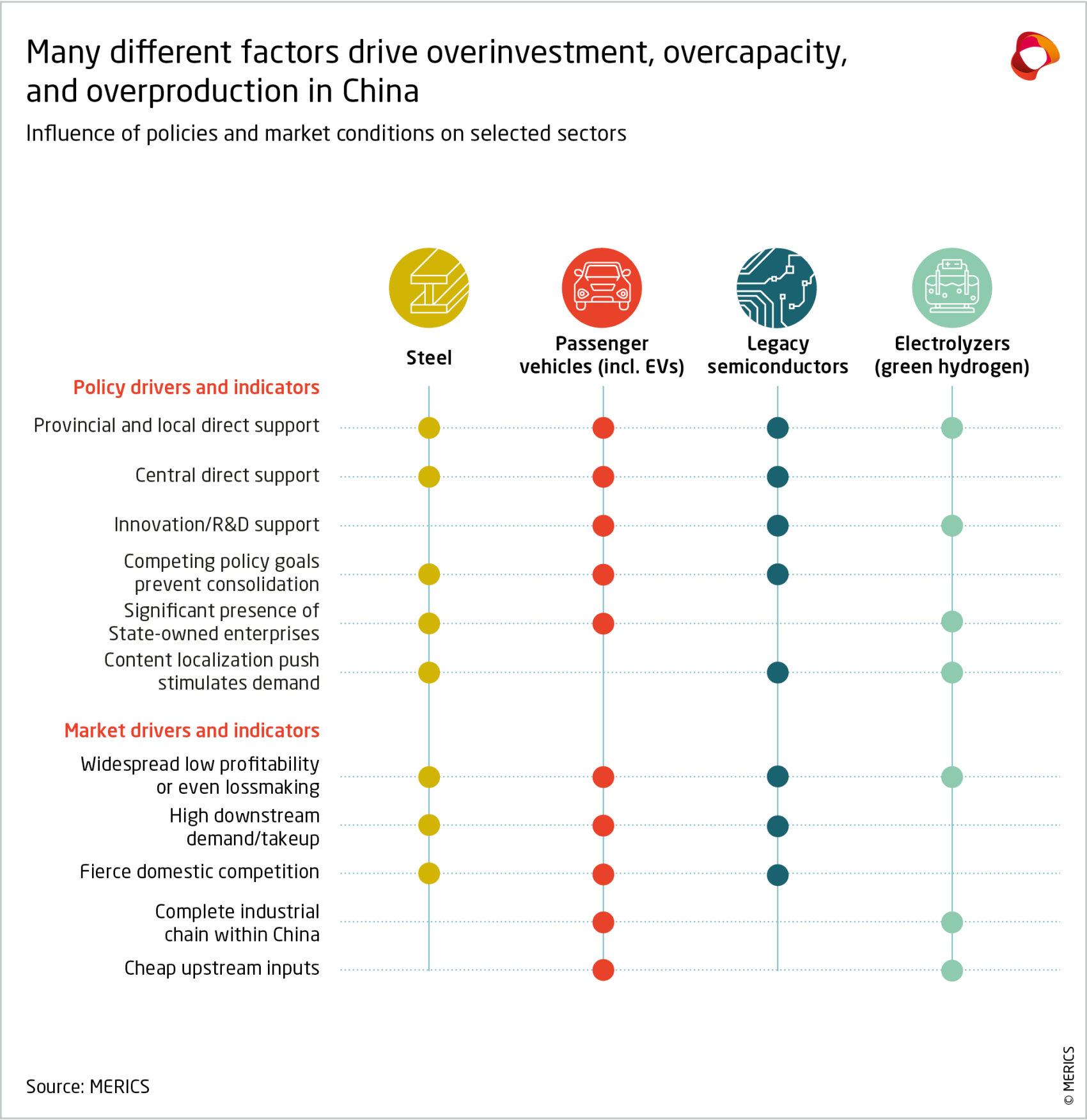

In a recent report, MERICS identified common drivers and indicators of overcapacity across four case studies, then highlighted other industries with the same drivers and indicators, making them more susceptible to overcapacity in the future. The results are concerning for European industry:

- In the short term: Legacy semiconductors, low- to mid-range industrial machinery and components, IT equipment, low- to mid-range medical devices, and pharmaceuticals.

- In the medium to long term: Electrolyzers, advanced medical devices, advanced industrial machinery and components, and new materials.

Has the situation worsened due to Trump's tariffs?

The spillover of Chinese overcapacities did not begin with Trump's tariffs and will not end with their “suspension”. The issue has impacted the EU for some time, as now painfully experienced by a growing range of sectors, particularly the automotive industry.

But it is too early to assess the impact of tariffs, and uncertainties created by their intermittency is creating a new dynamic. China’s exports rose in Q1 2025 over Q1 2024, with a decline in exports to the US more than compensated by an increase in exports to ASEAN (most likely partly to circumvent the tariffs on China) and to the EU. This is aligned with the recent trend, which is not likely to be disrupted by Donald Trump’s stop-and-go tariffs, even if they are disruptive.

In sectors where China exports goods to the US, we expect Trump’s tariffs to cause some exports to be redirected to the EU and third markets, intensifying competition for European companies. The impact will be greater where the EU has strong players, for example machinery and components rather than textiles and footwear.

It is less likely that the tariffs will open opportunities for EU firms in the US market. Evidence from the 2018 US-China trade tensions showed the gap in the US market was not filled by exports from the EU, but rather from South and Southeast Asia, which have a structure closer to China’s (and may be used by Chinese firms to reroute exports to the US).

Would an increase in Chinese demand be the silver bullet?

China’s domestic demand would need to grow significantly to absorb enough excess production to offset its current trade imbalances. It seems unlikely that the current leadership will change course in the economic system it has spent the last 12 years building. Beijing continues to prioritize the supply side of the economy over the demand side. That is unlikely to change, as the entire economic model depends on high savings rates and the deprivation of resources from households to fund industrial policy.

Even with a dramatic increase in consumption, China’s economic model still creates fundamentally different players than those in free-market countries. Because Chinese companies will continue to tolerate razor-thin margins thanks to offsetting government support, European companies, constrained by considerations like return on investment, efficient allocation of capital, and fiduciary responsibility will still face risks.

Can the EU and China resolve this through negotiations?

It is unlikely. The EU has repeatedly raised concerns about China’s industrial overcapacity, with Commission President Ursula von der Leyen calling it a key issue at the EU-China Summit in December 2023. Beijing has consistently rejected the charge, with China’s President Xi Jinping stating during his visit to Europe in May 2024 that “there is no such thing as China’s overcapacity problem.” Consequently, the EU focused on moving unilaterally – imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs calculated based on Chinese dumping in the sector. The Commission convened a high-level forum on “non-market overcapacity” in November 2024 to build momentum for new overcapacity-related policy instruments.

The return of Donald Trump and his use of “reciprocal” tariffs created space for a more amicable tone in high-profile exchanges between the EU and China. With the July EU-China Summit in Beijing and the deadline for Trump’s 90-day tariff pause approaching, chances for a negotiated solution between EU and China remain slim.

That would require Beijing to reverse some of the current prime directives of its economic strategy. EU-induced policy shifts will not be the driver of such change, which would require more fundamental reassessments. Still, the EU may expect some gives at the tactical level and management of the issue rather than resolving it.

What can the EU do in response?

In response to China’s market distortions, the EU can deploy its existing trade defense instruments (TDI): International Procurement Instrument, anti-dumping, countervailing duties, etc. In the short term, the safeguard measures on steel adopted during Trump's first term could be expanded to other sectors and adapted for a faster response. However, increasing DG Trade’s staffing is essential to enhance its investigation capacity.

The EU also needs an approach focusing on strategic sectors. In sectors like EVs and medical devices, the EU should reinforce trade defense instruments, while monitoring greenfield investments to make sure they effectively help reduce dependencies on China. Where there are security risks (steel, green tech, semiconductors, etc.), the EU should pair TDI with the promotion of local production, quotas, and content requirements. The EU could also further incentivize member states to restrict Chinese access to R&D in industries where future distortions are anticipated.

In addition, strengthening the single market and ensuring compliance with the EU’s high environmental and data protection standards can help the EU protect itself from unfair competition from abroad (via mechanisms such as the CBAM, EU ETS, or the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation).

What to watch out for?

China’s overcapacity may materialize through growing exports and higher investment, either directly or via third countries. China can export directly to the EU, but third markets are also intermediate export hubs and key markets in which European companies may face increased competition from China. It will be important to monitor signals that China sends to third countries (such as Xi’s outreach to Malaysia, Cambodia and Vietnam as well as Japan, Korea, Africa and Latin America). China’s trade agreements and cooperation with these countries will undermine both US and European companies’ competitiveness.

The outcome of the July EU-China summit will signal whether it is feasible to manage parts of the overcapacity challenge. Lifting sanctions on sitting MEPs (see more in Diplomatic Tracker below) may revive an appetite for deeper economic engagement, though China and the EU are unlikely to revive the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment given the shift in the geopolitical and economic climate since the EU shelved its ratification in 2021.

Still, in this new reality, overcapacity discussions could evolve into a broader negotiation of the logic underpinning EU-China economic engagement, but any potential progress would likely be only tactical. The EU must carefully distinguish short-term mitigation from the deeper, strategic challenge posed by China’s supply-driven, party-state economic model.

Read more:

- MERICS: Beyond overcapacity: Chinese-style modernization and the clash of economic models

- IFW: The consequences of the Trump trade war for Europe

- European Central Bank: The implications of US-China trade tensions for the euro area – lessons from the tariffs imposed by the first Trump Administration

- ECFR: Brussels hold’em: European cards against Trumpian coercion

Update

Germany’s China policy under Merz: A rocky road towards risk-aware pragmatism

By Claudia Wessling

After months of political deadlock, Germany has a new government. In the first days of Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s government, China was not yet a clear priority: Merz visited his European counterparts in France and Poland and traveled to Ukraine with French President Emmanuel Macron, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer. Merz also spoke to US President Donald Trump on the phone. The conversation was allegedly “remarkably relaxed and polite” (despite US tariff announcements that could considerably harm Germany’s export-oriented economy).

Germany’s new grand coalition of social democrats and conservatives has only revealed the broad outlines of its China policy. But there are a few indicators of where it is headed.

What you need to know:

The Coalition Treaty – A more pragmatic stance on China: The document the CDU, CSU and SPD agreed on in an arduous process does not contain much on China. The coalition pledges to revise Germany’s 2023 China Strategy “according to the principle of de-risking.” It wants to, for instance, expand research and expertise on security-related issues in defense, cyber security, infrastructure and disinformation. It highlights that China’s recent actions have put “elements of systemic rivalry” front and center, but at the same time also stresses that big global problems can only be solved in cooperation with the Chinese government.

Notably, the document does not mention the “partner, competitor, rival” formula that has defined EU relations with China since 2019. This is a sign that the Merz government, while keeping de-risking on the agenda, seeks a less ideological and more economy-oriented, pragmatic stance than the previous coalition of SPD, Liberals and Greens.

- The Merz cabinet – CDU/CSU-led ministries in the lead on China: As government bodies with the strongest focus on China are now all in the hands of the CDU or CSU – the chancellery, economics, foreign affairs, and, to a lesser extent, transport and research – policies across these institutions will now likely be more closely aligned. Friedrich Merz has so far presented himself as an advocate for a bolder German foreign policy, emphasizing the significance of transatlantic relations and a coordinated European approach as well as caution in dealings with China. He even described China as part of an "axis of autocracies" that challenges liberal democracies. To the dismay of some in business, Merz made it clear before the election that his government would not provide bailouts for failed investments in China.

- The new Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul (CDU) is known as a pragmatic politician. Vis-à-vis China, he can be expected to focus on balancing economic interests with strategic considerations. The seasoned parliamentarian has, behind closed doors, shifted his party to a more critical China stance. On the other hand, together with fellow CDU/CSU MPs, he once participated in dialogues with members of China’s National People’s Congress and Chinese Communist Party officials. He recently described his position as staying engaged with China while remaining clear-eyed about the two countries’ differences.

- Katherina Reiche (CDU), the new Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action and a former MP, worked as a top manager in the energy sector for several years before entering the Merz government. She has previously been open to China cooperation in clean energy and hydrogen tech, while also emphasizing the need for clear guardrails and a “green industry diplomacy.”

- The new Minister of Transport Patrick Schnieder (CDU) has in past speeches emphasized the need for diversification. He has called India, for instance, “an indispensable strategic partner for Germany,”, especially in “defending common liberal, democratic, and security interests in the face of the new great power ambitions of authoritarian systems” (like China).

- The new Minister for Research, Technology and Space, Dorothee Bär (CSU) is one of the new government’s more tech-savvy policymakers. She has called for more assertive engagement with China, especially in future aviation and digital industries. Her take: Chinese tech firms should not be demonized, but rather closely scrutinized.

- German business wants more China engagement and de-risking guidance: The new government will face pressure from German business, still heavily engaged in and increasingly dependent on innovation happening in China. Companies from a range of sectors have called for more intensive partnerships with Chinese counterparts in order keep up with innovation. Reciprocity remains high on the agenda, not only regarding market access in China, but also knowledge transfer. Other demands include the need for more (and not less) engagement of German companies in the Chinese market and Berlin’s support in establishing clear rules for cross-border data transfer with China. In the de-risking discussion, business is increasingly critical of the contradictions in pressure for localization (in China). Companies have called for concrete guidance and support to reconcile both trends.

Beijing hopes for an improvement in relations: Xi Jinping has reacted positively to Merz’s election. According to party-state news agency Xinhua, Xi expressed hopes of opening a new chapter in the “strategic partnership” with Europe and steering cooperation between China and the EU in the “right direction.” An editorial in China Daily even evoked the former glory of vibrant economic relations by recommending that Merz should “build on the past for the future.” The next weeks and months will show how the new chancellor will navigate the challenges of an increasingly competitive China on the one hand and a more confrontational US on the other.

The Merz administration’s stance in early China-Germany exchanges, the position it takes on screening Chinese investments in Germany, and how it balances the voiced commitment to pursuing a European approach – amid German business pressure to prioritize national economic interests – will indicate what this new government means for EU-China relations.

Read more:

- MERICS/Hinrich Foundation: Germany’s dilemma over strategic calibration with China

- Die Welt: Merz und Macron: Einen diktierten Frieden werden wir niemals akzeptieren

- Le Figaro: Emmanuel Macron et Friedrich Merz : “Il faut remettre à plat les relations franco-allemandes pour l’Europe“

- Deutschlandfunk: Xi congratulates Merz after election to chancellor (in German)

- China Daily: Merz should build on the past for the future

- Bloomberg: German Frontrunner Merz warns companies against China investments

- AHK Greater China: Business sentiment survey 2024/25: German companies plan to maintain operations in China

EUROPE-CHINA DIPLOMATIC TRACKER

- A diplomatic offensive is unfolding. Beijing is lifting sanctions on sitting MEPs and Committees of the European Parliament in response to the EP’s loosening of internal guidelines on engagement with Chinese representatives – completed despite a scandal surrounding Huawei’s lobbying activities in parliament. The move may rekindle the appetite for a negotiated economic agreement with China, but a return of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment in the form negotiated at the end of 2020 is unlikely.

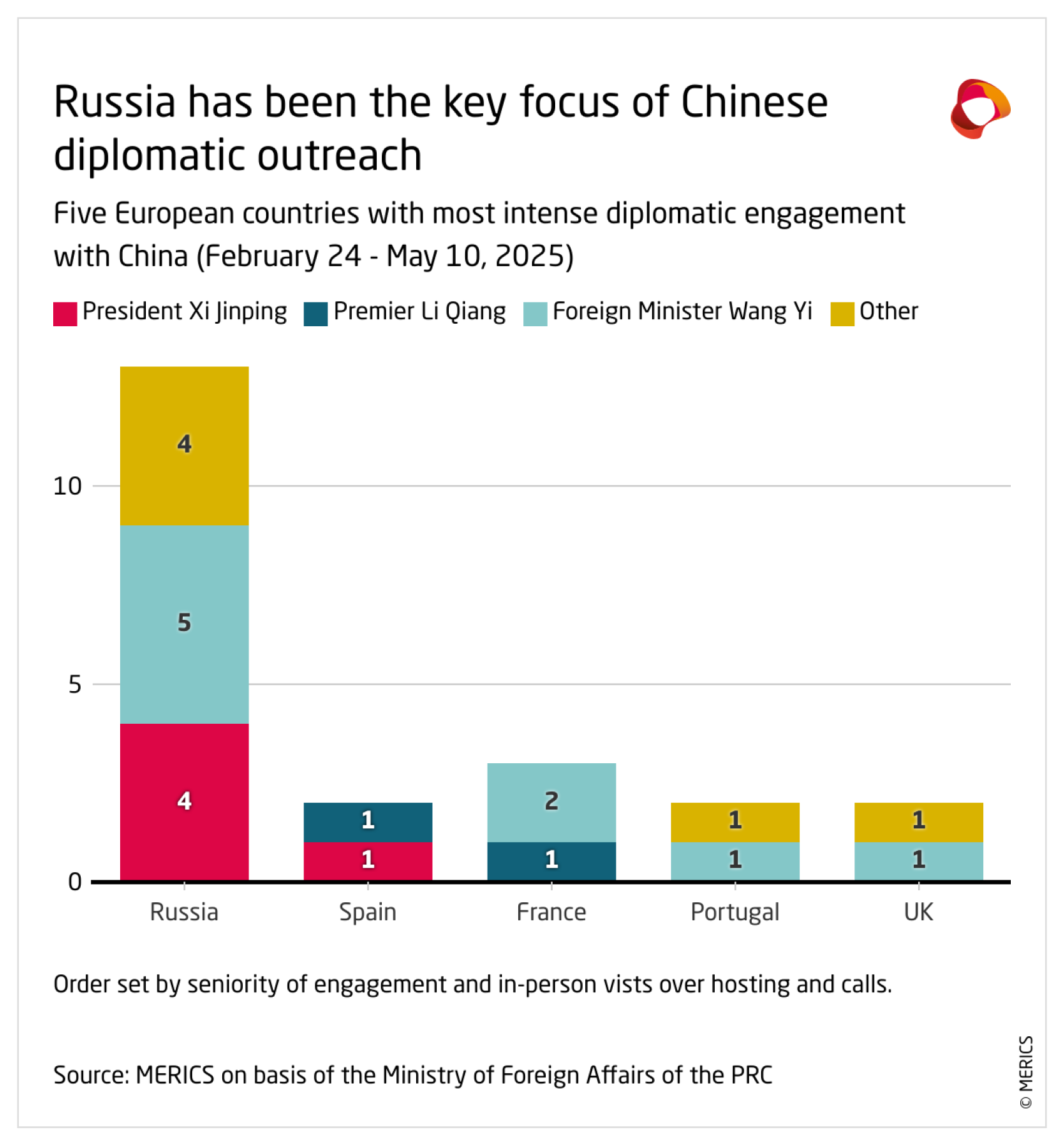

- In a clear sign of priorities of China’s diplomatic outreach in Europe at the time of Trump-induced uncertainties, between February 24 and May 11, Chinese top leadership engaged with Russia alone nearly as frequently as with all EU member states combined and at a higher leadership level. Despite the 50th anniversary of EU-China relations on May 6, Xi had no time to visit the EU for the summit taking place in Brussels. But he flew to Moscow on May 7 for a four-day visit, including participation in Russia’s WWII Victory Day Military Parade and releasing a joint statement on global strategic stability. The visit provided an opportunity to meet with Serbian and Slovak leaders, who were also visiting Moscow.

- Some key EU countries have been engaging with China to potentially expand existing trade agreements with emphasis on agrifood sector. This increased engagement without clear European messaging plays into Beijing’s aim to project a united front in opposition to Trump’s tariffs and create the impression that EU members support China’s bid for multipolarity.

Spain had the most high-level engagement with China in recent months with Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez visiting Beijing on April 10-11. The two sides signed a 32-point action plan to strengthen the bilateral Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between 2025 and 2028. The plan involves trade and investment, agriculture, science and innovation and people-to-people exchange.

In line with this, Madrid also signed seven agreements aimed at facilitating exports of Spanish food, health and cosmetics products as well as culture, science and education agreements. In a telling contrast, the Spanish readout focuses on the agreements, while China’s focuses on multipolarity and the need to oppose the “tariff war.” Notably, only the Chinese readout mentions Ukraine, in the context of views exchanged on the “Ukraine crisis.”

France, China’s top agricultural import partner in the EU, combined agrifood discussions with those on recent geopolitical changes. In terms of concrete outputs, the two countries established a new rapid coordination mechanism for their "from French farms to Chinese tables” scheme to improve cooperation on food supply chains and issued a joint statement on climate change.

On May 15, the two countries also conducted the 10th France-China High-Level Economic and Financial Dialogue that paired calls for a coordination on multilateral system and “safeguarding an open and cooperative international economic and trade environment” with signing of bilateral cooperation documents regarding poultry industry.

Soapbox-MERICS Data Highlight

Germany has been asleep at the wheel in the face of China’s EV policy

| The Soapbox-MERICS Data Highlight offers data visualizations of EU-China economic relations. We have partnered with trade specialist Rafael Jimenez Buendía, Lecturer of International Trade at Taltech University in Tallinn, Estonia, and co-founder of “Soapbox,” a free weekly newsletter focused on China trade. In this edition, Rafael zooms in on German and European trade with China. |

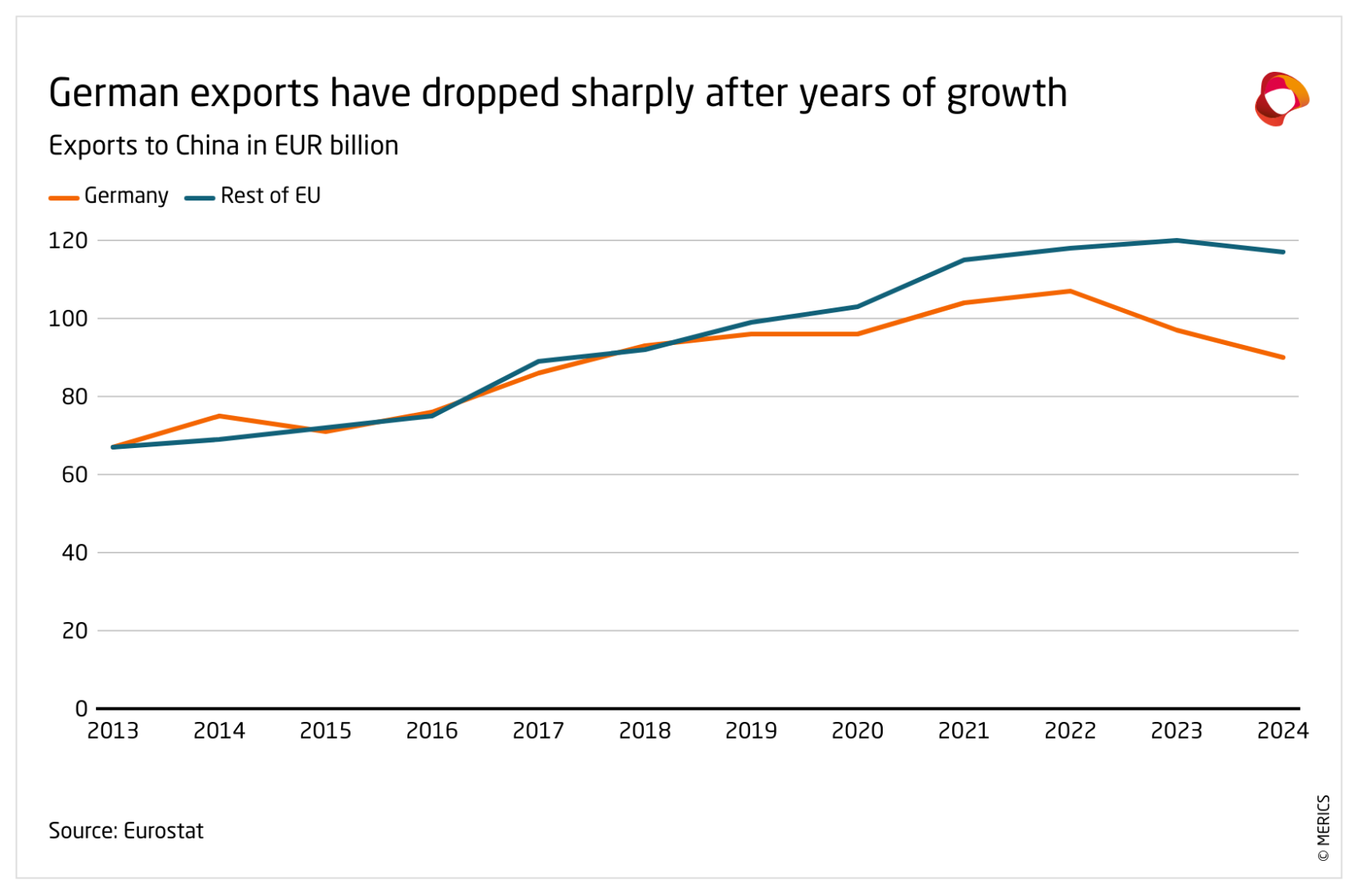

“Between 2013 and 2022, Germany's car exports to China grew by an average of 7 percent per year. In contrast, Germany's other exports to China – excluding automobiles – grew at a more modest rate of 5 percent annually. In 2022, however, everything changed. Between 2022 and 2024, the share of cars in Germany’s total exports to China fell to 16 percent on average annually from 19 percent in the period 2013-2022.

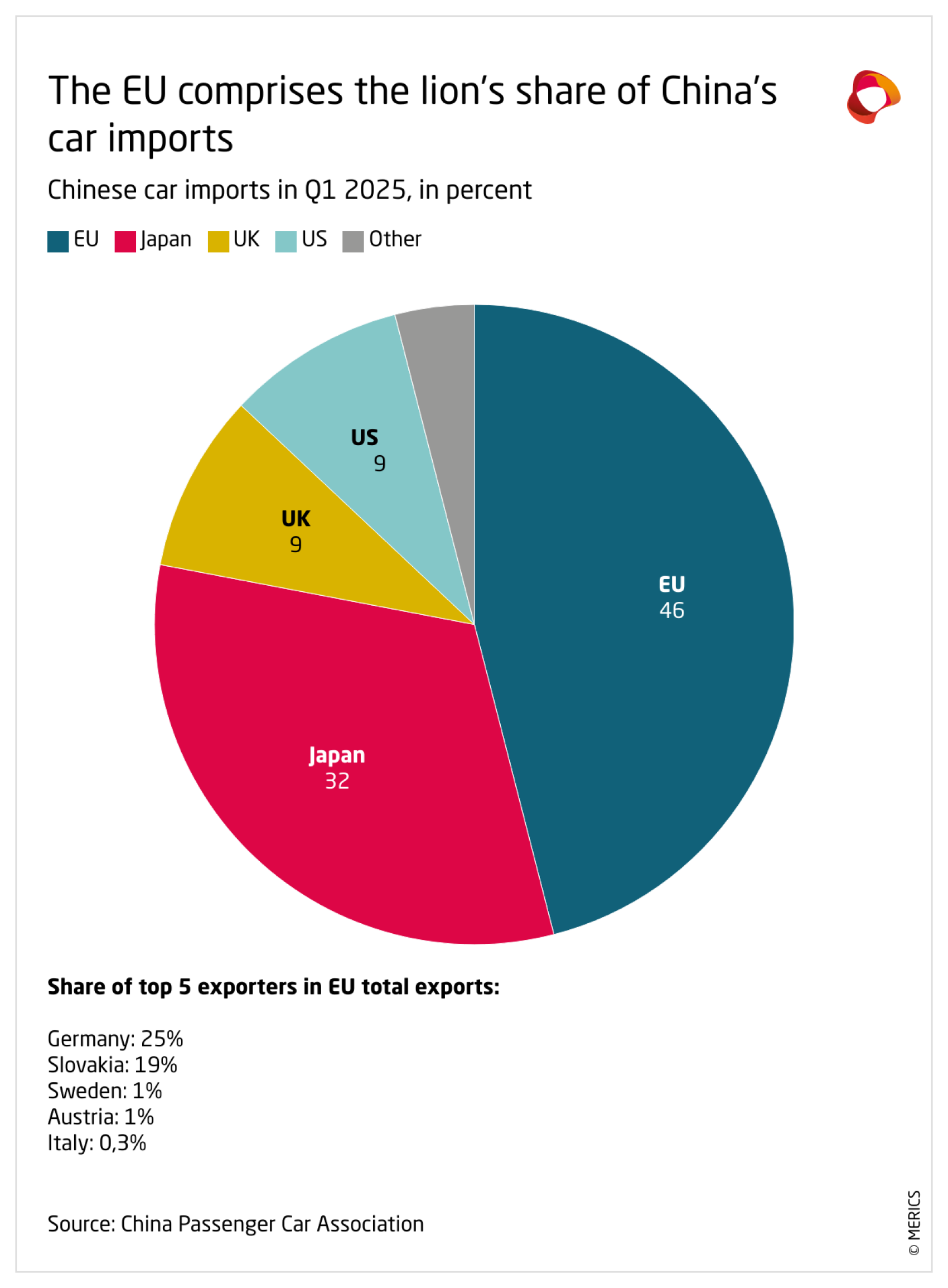

Since their peak in 2022, Germany’s non-automotive exports to China have decreased by 10 percent, while car exports have dropped by a considerable 44 percent in total. This decline is not due to a loss of market share to other exporters. German cars still account for 29 percent of all vehicle imports to China. What has changed is China.

The German automotive industry, like much of the global sector focused on combustion engines, failed to anticipate China's shift toward electric vehicles. Maintaining market share is no longer enough when the market itself is shrinking. In the first quarter of 2025, China imported 65 percent fewer foreign cars compared to the same period in 2022 – a fundamental shift that Germany, a key player in the sector, failed to foresee.”

Short takes

The US and UK sign trade deal with China in the background

The May 8 Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD) lifts targeted tariffs on British steel and cars while opening UK markets to an estimated USD 6 billion in US goods. It also includes a broader commitment to align on economic security, outlining measures such as tighter export controls, investment screening, and supply chain protections – provisions widely seen as aimed at China.

Beijing quickly condemned the deal, asserting that international agreements should not target third parties and warning that the UK risks becoming a conduit for US-led containment efforts. The agreement came just days before Washington and Beijing announced a 90-day tariff truce that cuts American duties on Chinese goods from 145 to 40 percent and has Beijing easing its retaliatory measures.

- Financial Times: China attacks UK trade deal with US

- UK Department for Business and Trade: US-UK Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD)

European Parliament backs EU-wide rules to tighten foreign investment screening

The move is a step toward updating the fragmented 2020 framework of FDI screening, introducing mandatory screening across member states. It could lead to higher thresholds for reviewing investments and greater protection for critical infrastructure. Positioned as a key policy instrument for EU resilience, the law targets risks tied to foreign – particularly Chinese – control over sectors like media, critical infrastructure, and raw materials. The decision highlights the sustained commitment to the EU’s de-risking agenda despite an ongoing thaw in relations with China.

- European Parliament: European Parliament endorses new screening rules for foreign investment in EU

EU’s rollout of trade defense measures on China continues

The bloc is set to impose anti-dumping duties of up to 131 percent on Chinese vanillin by late July, following a complaint by Belgian multinational Syensqo and an investigation launched in May 2024. It mirrors a US finding in January 2025 that China is dumping vanillin and follows the EU’s January 2025 decision to impose definitive duties on Chinese titanium dioxide, as Brussels presses ahead with trade defenses.

- EUR-Lex: Notice of initiation of an anti-dumping proceeding concerning imports of vanillin originating in the People’s Republic of China

- European Commission: EU acts to counter dumping of titanium dioxide from China

Former Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen visited Europe May 10-14

The move was her second trip to the continent since leaving office. Focused on promoting regional security and democratic values, the visit included stops in Lithuania, Denmark, and the UK. Tsai met with former Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė, attended the Copenhagen Democracy Summit, met with several UK lawmakers and visited the parliament. The trip comes amid heightened military tensions around Taiwan, following China’s "Strait Thunder – 2025A" military drills in early April.

Europe-China Resilience Audit

MERICS has analyzed readouts issued by governments after their leaders engaged with Chinese counterparts between 2019 and 2024: less than 40 percent of China’s official summaries in English were matched by an English-language communication from the European side – and even when they were, European readouts were on average 40 percent shorter and much less detailed. This shows that European Union (EU) member states are not taking the competition to shape the narrative of EU-China relations seriously enough. To learn more, read our latest analysis by MERICS Senior Analyst Grzegorz Stec on “How Europe is throwing the strategic communication game with China and how it could go all in” here.

This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page here.