Member states’ resilience efforts fall short of looming challenges: Europe-China Resilience Audit Update 2025

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

Introduction

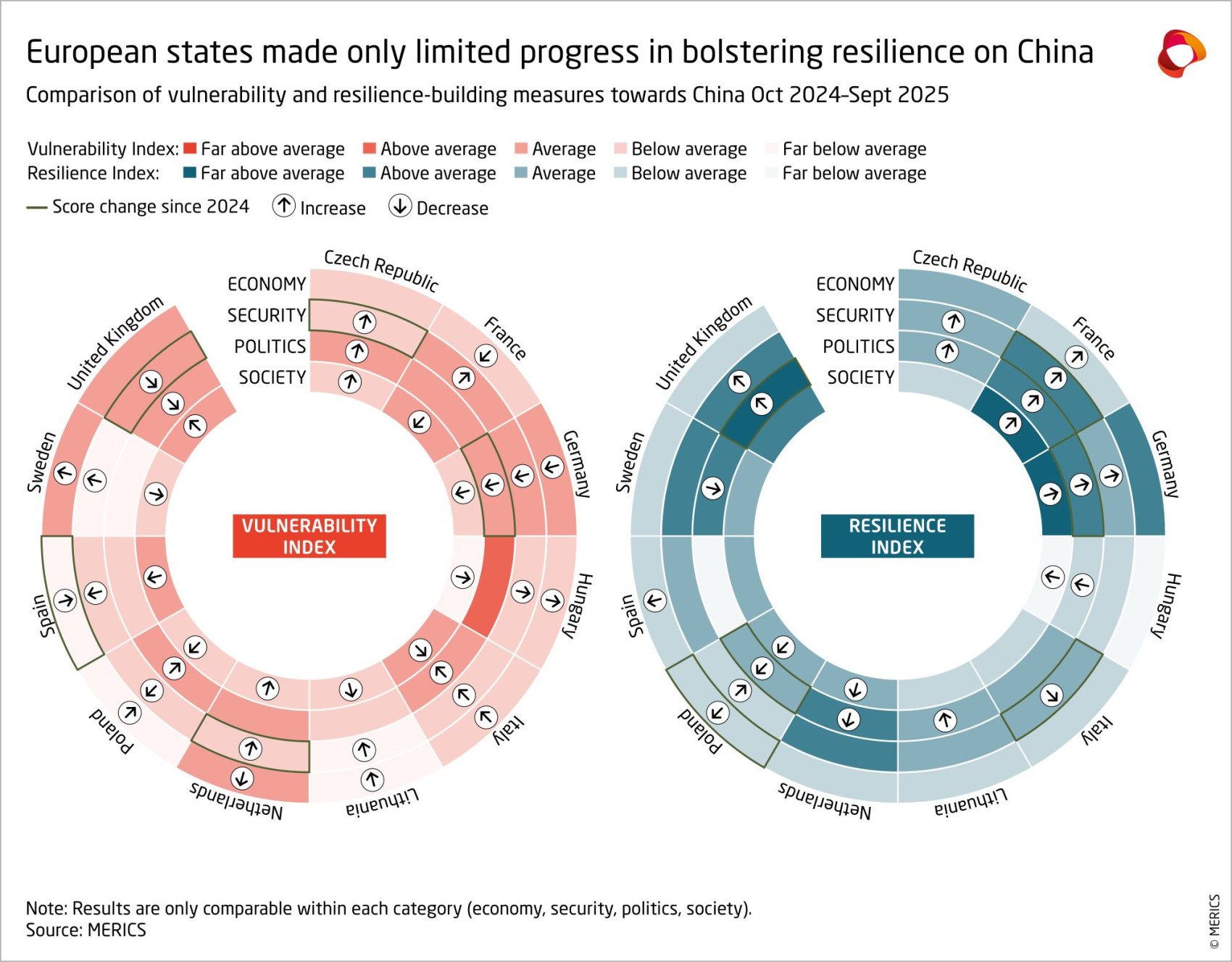

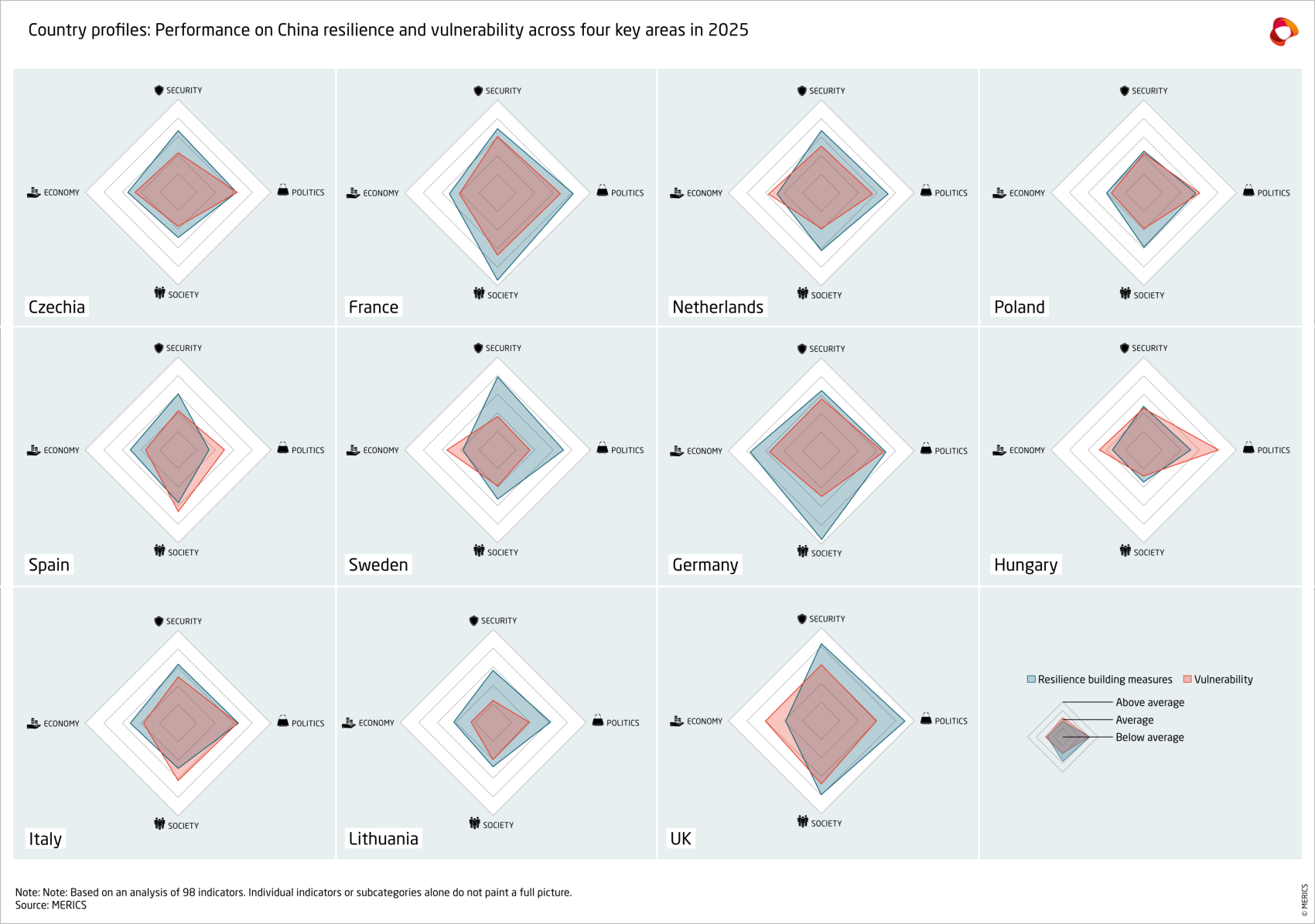

MERICS’ Europe-China Resilience Audit maps China-related vulnerabilities and resilience-building measures, based on 98 indicators, covering 11 European countries. The 2025 update indicates there have been only limited improvement in resilience-building and reducing vulnerabilities since the autumn 2024 report.

Progress remains insufficient in scale and pace given Beijing’s clear readiness to exploit EU vulnerabilities. The EU needs to brace for more pressure and friction in relations with China.

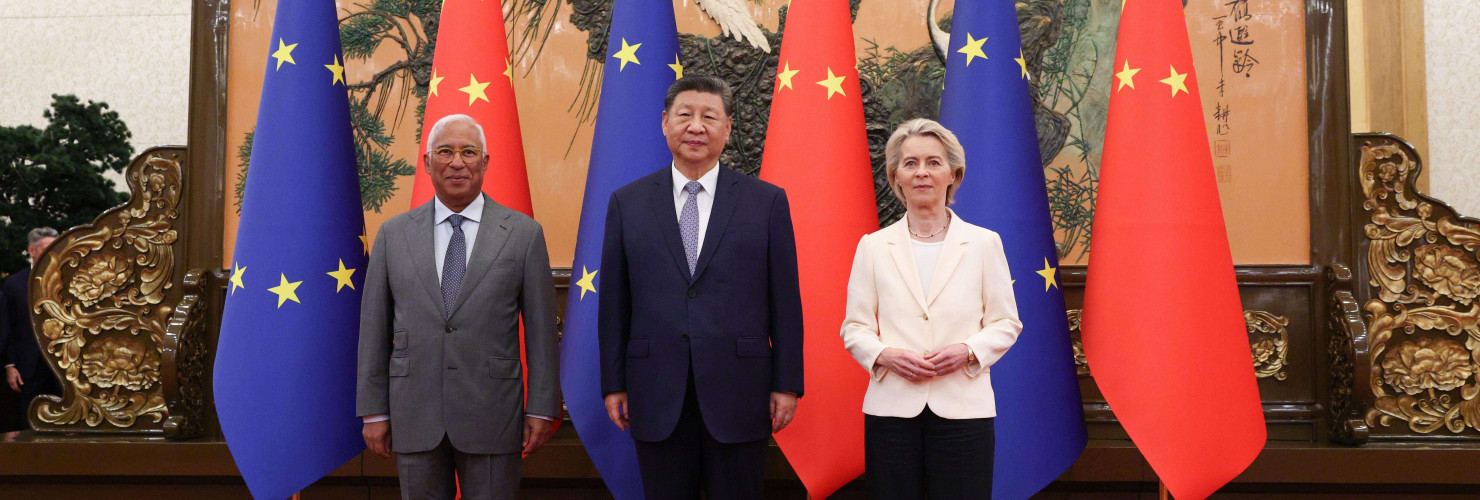

In the first half of 2025, the EU and many member states sought engagement with Beijing to explore whether its leadership might be more open to addressing the EU’s concerns in light of current shifts in the geopolitical landscape. But a lack of progress prompted the EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to declare that the EU-China relations had reached “a clear inflection point.”

Indeed, China has applied its instruments of economic statecraft more actively and even pre-emptively – also toward the EU – since US President Donald Trump returned to the White House in January.

Beijing’s rare earths licensing restrictions, which it continues to expand, are a threat to critical EU industries, including its strategically vital defense sector. Beijing’s techno-industrial system is colliding with more and more sectors of the European economy, already affecting the battery and automotive industries. Paired with an increasing trade imbalance, this undercuts the EU’s ambition for reindustrialization. China has also signalled its intent to respond to the EU’s trade-defense and de-risking measures, for instance, by banning European companies from major public procurement contracts for medical equipment or by targeting European agrifood exports (including through duties on cognac and pork and an anti-subsidy investigation into dairy).

The EU urgently needs to improve its ability to withstand similar pressures and limit Beijing’s leverage to ensure it can protect its interests. Such resilience-building and de-risking efforts are not geared toward decoupling or limiting interlinkages with China across the board, but toward ensuring the EU’s ability to manage risks without compromising long-term development.

Yet, building resilience on China is a tall order, especially with EU budget constraints due to increased defense spending, the focus on competitiveness and a push for deregulation, all while policymakers are focused on the US agenda. It requires sustained commitment from member states in areas where they hold specific competencies making action only through EU-level insufficient. But such political momentum on China resilience is currently lacking.

Limited progress of European countries in developing resilience or reducing vulnerability

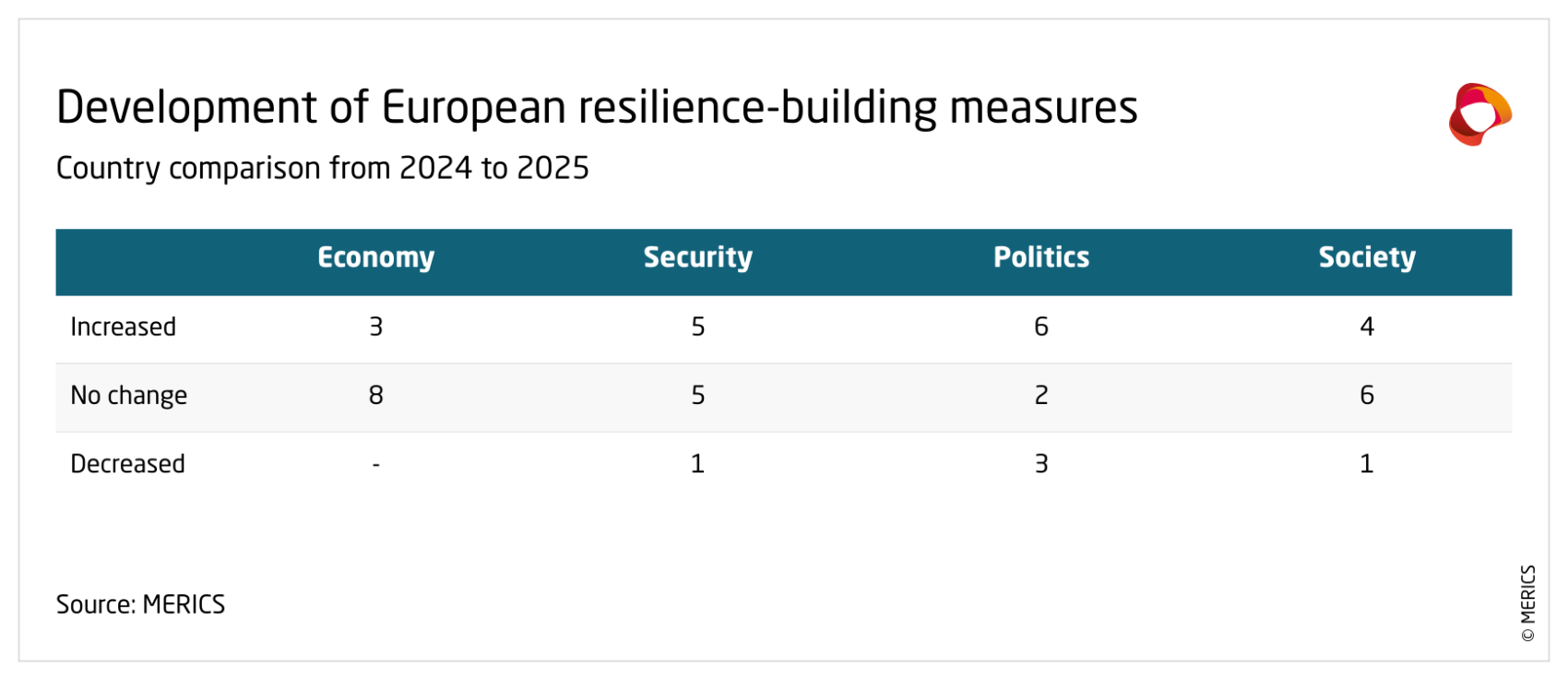

The analysis of 98 indicators – divided into categories of economy, security, politics and society – shows overall limited progress in developing resilience or reducing vulnerability toward China over the past year.

Across the 11 countries, there was no improvement, and in some areas even a decrease, in 26 of 44 areas of potential resilience-building measures. But in several cases where there was improvement, resilience-building was incremental and due only to progress in an individual indicator rather than a major intentional push. Also, countries continue to diverge considerably in some of the key measures, showing the scattered and uncoordinated nature of resilience-building on China across Europe.

Five countries showed progress to an extent that they improved their categories: France, Germany, Italy, Poland and the UK.

- France revised its Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) screening regulations in 2024. Now, it is mandatory to notify the Ministry of the Economy when non-EU/EEA investors increase their voting rights in a French listed company to over 10 percent (previously 25 percent).

- Germany expanded the number of China experts funded through and accessible to the administration, and the number of China-related motions in its parliament rose slightly.

- Italy introduced a new knowledge and research security framework and platform.

- Poland strengthened its cross-administration China coordination mechanism, launched a network of China-focused contact points in strategic embassies and adopted an Economic Promotion Policy that supports diversification.

- The UK conducted a dedicated China Audit, which despite some controversy over transparency of the process and delays represents an effort to improve government’s situational awareness and paved the way for a more coordinated China policy.

Vulnerabilities remained the same or increased in 24 of 44 categories. This reflects, among other things, that six countries increased or retained the use of Huawei and ZTE equipment in their telecommunication networks and that Europeans’ exposure to TikTok is generally growing – both indicative of wider challenges in the digital domain.

The reduction in economic vulnerabilities is largely a result of shrinking exposure rather than a sign of increasing economic wellbeing of European economies. It stems from decreases in exports to China, lower income from FDI in China as a share of GDP, and rising hurdles for firms – reflected in a slight dip in memberships at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. That means the reduction is largely a byproduct of China raising barriers for European actors rather than a result of deliberate European policies to reduce vulnerabilities.

Five countries noted changes significant enough to shift between tiers:

- Czechia: Significantly expanded the presence of Huawei and ZTE in national 5G infrastructure between 2022 and 2024 from 0 to 67 percent.

- Germany: With a lower number of engagements and joint announcements with China throughout the past year - partially fueled by diplomatic slowdown amid government transition - Germany was less exposed to potential risks of indirectly endorsing Beijing’s narratives. However, less engagement is a double-edged sword as it limits the channels to navigate growing frictions in already fraught bilateral relations.

- Netherlands: Significantly decreased the presence of Huawei and ZTE in national 5G infrastructure between 2022 and 2024 from 72 percent to 37 percent.

- Spain: Despite a greater push to attract Chinese investments, data shows a small relative decline in importance of China to the Spanish economy, which pushed Spain to a lower vulnerability threshold. This is primarily because Spain’s revenue from tourism from China and Hong Kong as a share of GDP decreased from 1,29 percent of Spanish GDP to 0.37 percent. FDI from China decreased slightly as a share of Spanish GDP over the past five years.

- UK: The country has limited Chinese ownership in critical industries such as steel (with the government taking operational control of British Steel from its Chinese owner, Jingye Group, and nuclear energy after the government bought China General Nuclear Corp.’s share of the Sizewell C power plant. There are now indications CGN will be effectively removed from Bradwell B project, where it was set to be the lead developer.

Read more on resilience-building in the 11 surveyed European countries here.

Five resilience audit takeaways

1. European resilience building on China remains fragmented and uncoordinated

The scattered progress in resilience building over the past year reflects a broader issue: Member states are not coordinating their resilience-building measures, leaving gaps for Beijing to exploit in gaining leverage or access to the European ecosystem.

For instance, as of this year, member states still differ in their national definitions of critical infrastructure. For instance, they diverge in areas such as the clear inclusion of space, nuclear, or media sectors in that category.

The divergence remains the case also for FDI screening mechanisms. Countries maintain different mandatory notification thresholds ranging from 10 percent ownership by non-EU/EEA entities to over 20 percent and covering different sectors.

This also is clearly visible in research security measures. Only the Netherlands and the UK have institutionalized frameworks. Italy is putting a new support system in place, four states have issued guidelines, and four have no concrete measures.

Read more on EU trade vulnerabilities here and on export controls here.

2. Digital resilience urgently needs to be strengthened – from 5G to IoT

In the digital space, responses to threats and challenges emanating from China are not improving at a sufficient rate, and in some cases, resilience is worsening.

More than half a decade after the EU unveiled its 5G toolbox, not all member states have introduced national regulations. Czechia and Hungary lack clear regulations and Polish government released a draft of law allowing identification of high-risk telecom vendors only in October 2025.

Furthermore, between 2022 and 2024, four countries increased, five decreased, and two maintained the same share of Huawei and ZTE equipment in national 5G telecommunication networks.

This is also the case for more specific restrictions in the public sector. Only five of 11 surveyed states have specific regulations on the use of Chinese smartphones and apps by public officials, with only a single addition compared to last year. No progress was noted on regulating the use of Chinese tech in public buildings (e.g. surveillance equipment), as only two countries have such regulations.

At the same time, the exposure of the broader European population to China-linked products is growing. For instance, the average share of the population using TikTok has grown to 37.3 percent this year from 31.89 percent last year, while Chinese electric vehicle (EV) brands, oftentimes offering digitally connected vehicles, doubled their market share in the EU in the last year.

This shows how China’s digital advancement is bringing more digital products and connected devices to Europe, be it connected cars and a range of IoT and AI-powered products and solutions ranging from security devices, smart wearables to toys. The window to act and preemptively build resilience in this field is narrowing. European states are struggling to keep up. For instance, so far only the Czech Republic and the Netherlands have officially released regulations on the usage of the Chinese AI tool DeepSeek by public officials.

Read more on China-made connected vehicles here.

3. National China policies need more clarity and coordination

Over the past year, only the UK conducted a new major, publicly communicated effort to assess the relations with China through a dedicated audit. Among the surveyed EU states, only Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden have issued dedicated China strategies or public communications, but the latter two did so back in 2019.

Even more important than strategies are mechanisms that help align different government agencies on China policy on a rolling basis. Based on a confidential survey, most member states lack such coordination frameworks. In many cases, coordination continues to take place only ad hoc ahead of high-profile exchanges with Chinese counterparts. Save for one, no country declared a notable increase in the size of the China team within their foreign ministry.

While growing, political debate on China policy remained limited. Most parliamentary databases of the EU member states surveyed revealed an average of less than 40 motions on China-related matters over the past three years. Electoral party programs rarely address China.

Read more on the lack of will to pursue strategic communication with China here.

4. China knowledge needs to be better integrated into administrations

As China’s measures increasingly present cross-sector challenges and generates sudden instabilities requiring rapid responses, governments must improve their capacity to respond to China’s actions and develop a more proactive and informed China policy. That means developing basic China knowledge across administrations and establishing channels for bringing in highly specialized knowledge when needed.

Most governments still lack a systematic approach to China knowledge building within their administration. The UK and the Netherlands do so in the most institutionalized way through dedicated trainings via the Great Britain China Centre and the Dutch China Knowledge Network (CKN).

As for structured ways for administrations to engage external knowledge, there are several active models. They range from the fully funded Swedish National China Centre (NKK) to the Dutch government’s coordinated network approach, and support of existing institutions as in the context of the German Federal Foreign Office and MERICS. Other noteworthy solutions include dedicated China fellowships bringing experts into administrations or secondments of administration personnel to think tanks.

However, broader efforts to expand national China knowledge and situational awareness are still limited. Only five of 11 countries said they had a dedicated national funding scheme for China research. Member states are not supporting journalism, as six of 11 countries have fewer than five correspondents in China, with four having none or just a single correspondent.

Read more on China competence building in European national administrations here.

5. Countries lack political will and action for building China resilience

Progress on resilience hinges less on drafting new policies than on implementing them. For instance, in Hungary, the introduction of resilience building measures, such as foreign direct investment screening, has not translated into implementation vis-à-vis China.

The limited progress of the EU and many of its member states in improving resilience can be broadly explained by a lack of political will to act and limited prioritization of China policy. Based on foresight workshops and expert opinion forums that have been part of the China Horizons project, this tendency is likely to remain in place due to four trends:

- Political focus shifted to Washington: The return of Donald Trump and the ensuing tensions in transatlantic relations impacting European defense have taken priority over China policy, leaving limited bandwidth for European leaders to address the topic. Furthermore, transatlantic tensions have disrupted cooperation and dialogue on China, which previously motivated member states to align with Washington or to develop a distinct European position.

- Engagement competition puts member states in a reactive mode: The EU and member states struggle to navigate the intensifying US-China competition. Seeking to optimize their position amid geoeconomic realignment, member states want to keep their options open. The EU’s US and China policies are becoming increasingly interlinked, and the pace of US-China competition has put the EU in a reactive mode, limiting momentum for bold, assertive action on China policy.

- Economic disruptions have increased the appeal of opportunities – including those from China: The appetite for Chinese EV investments or agri-food exports has focused member states on short-term gains and made them less willing to pursue assertive China policy in fear of retaliation or opportunity costs.

- Domestic constraints limit resources for assertive China policy: The increase in defense spending is taking priority and consuming the bulk of available resources. Paired with anxiety over the potential rise of the populist and far right parties alongside pressure for deregulation, European capitals are keen to limit costs.

Read more on transnational repression and extraditions here.

Options for action: more coordination and investment in China capabilities are key

Align more:

The EU could expand its use of directives, which must be transposed into national legislation, on issues such as cybersecurity or critical infrastructure, to ensure member states are better aligned in policymaking on China. In areas where a directive is not legally or politically possible, the EU should support member states’ alignment through new guidelines and risk-assessment frameworks. Those could then be promoted through organizing “coalitions of the willing” or clubs of member states that can grow over time. Where possible, access to EU funding could be made conditional on implementing specific risk-mitigation measures.

Develop digital measures:

Building on the experience of the 5G toolbox, the EU should intensify its work on coordinated data and cybersecurity risk assessments of China-related platforms (such as cloud services), devices (such as smartphones or connected vehicles) and specific components (such as chips). The new regulations such as the NIS2 directive that introduced common cybersecurity standards for strategic entities in 18 sectors obliged the member states to introduce ways of making cybersecurity decisions based not only on technical but also on political risks. The member states should use such abilities in a more flexible and intentional way, such as allowing selected Chinese products but ensuring they are used with European software.

Structure China coordination:

EU member states could consider appointing national China coordinators tasked with linking government workstreams. The Netherlands offers a model with the role of a coordinator on China & Economic Security Permanent Representations to the EU and NATO. Such coordinators could also engage business, experts, academia and civil society and channel their work into durable national China strategies or guidelines. At the EU level, the bloc could establish a “European China House,” modeled on the US interagency network, to connect the Commission, EEAS, the Council, member states, and other stakeholders and improve China policy coordination.

Invest in China capabilities:

Aside from developing domestic capacities based on models in other member states, European governments and the EU should increase efforts to pull together and coordinate the resources on China across the EU to build an autonomous European China knowledge system. This can include supporting efforts such as Horizon Europe funding for China research (ideally through long-term thematic grants) or engaging with initiatives that seek to structure knowledge transmission from the China expert, academia, business and civil society communities to decision makers.

Plan more tactically, act and evaluate:

Member states should consider developing and updating internal government short- to medium-term China action plans. Those could help to prioritize and provide direction. At the EU level, this could take the form of recurring planned discussions on China during European Council summits and relevant Council or the EU meetings coordinated via the “European China House.”

Appendix

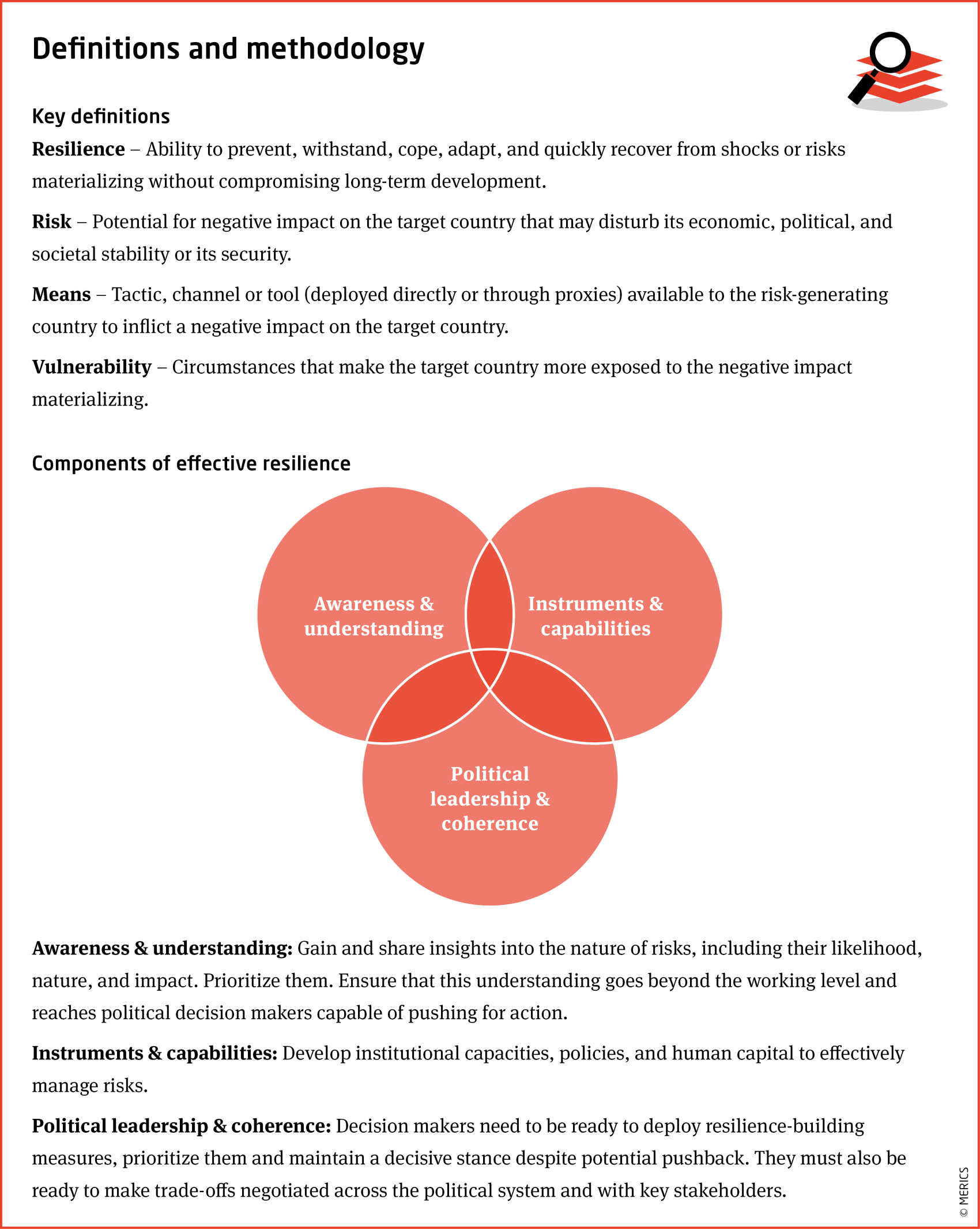

Appendix 1: Definitions and methodology

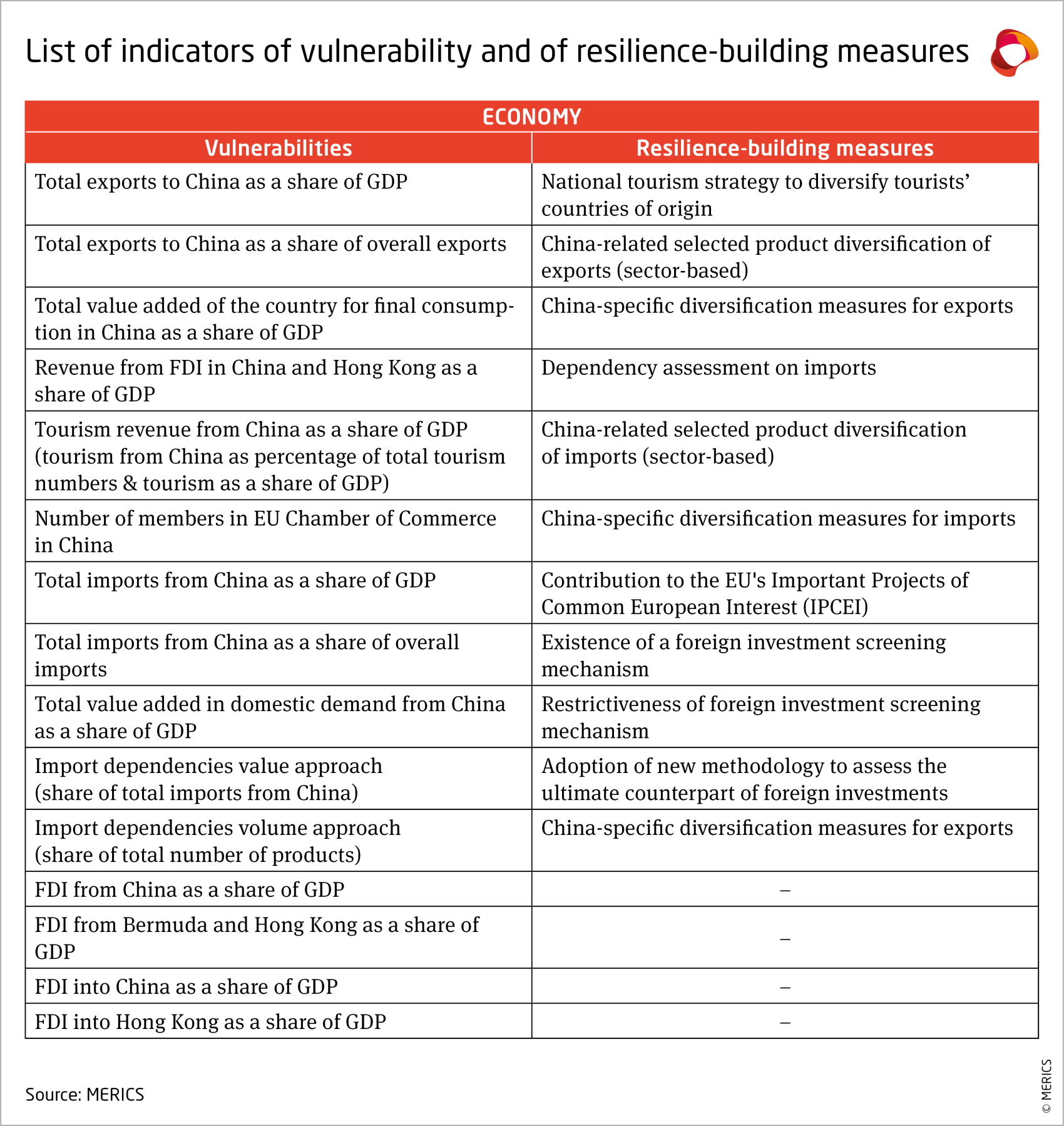

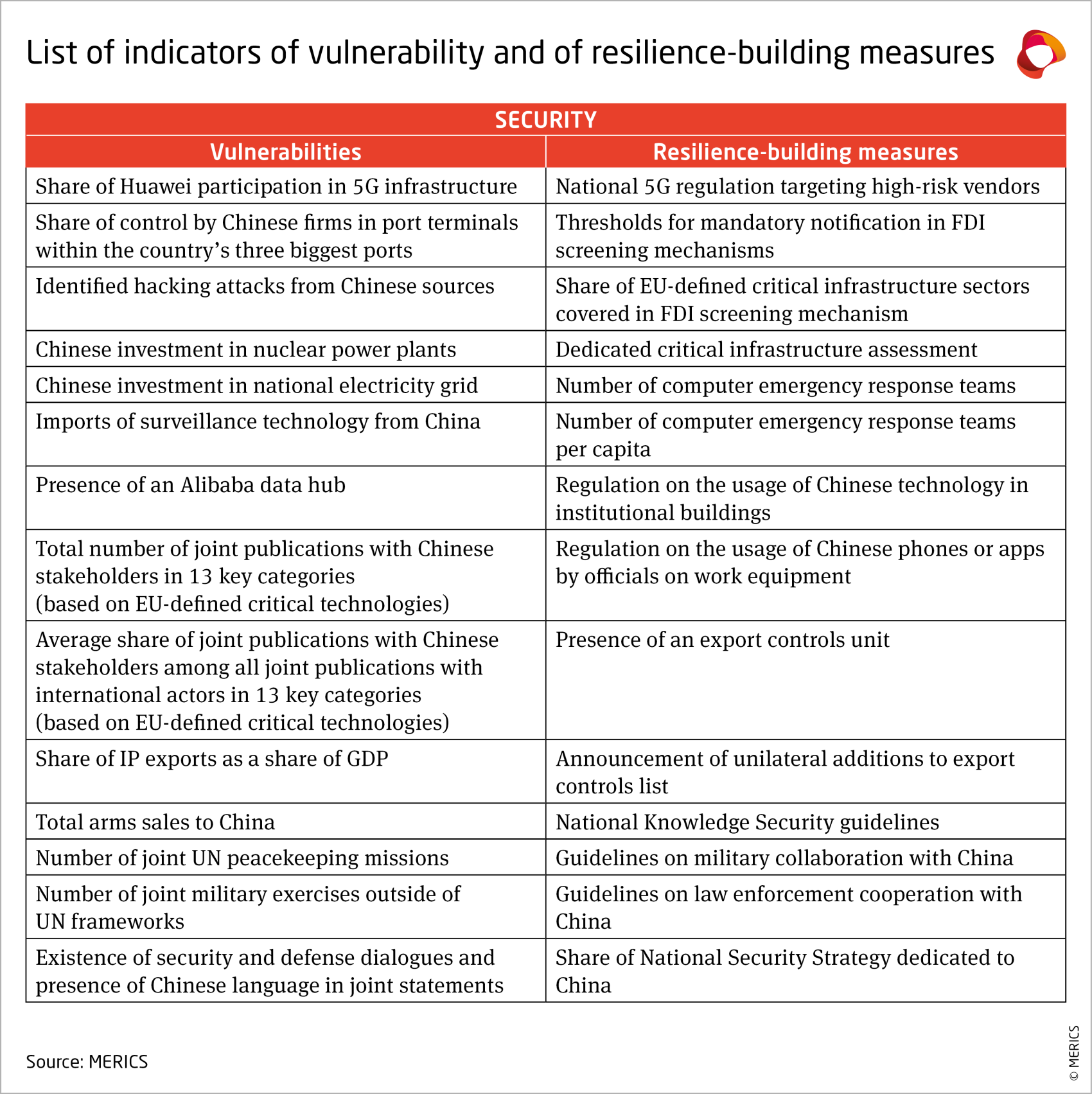

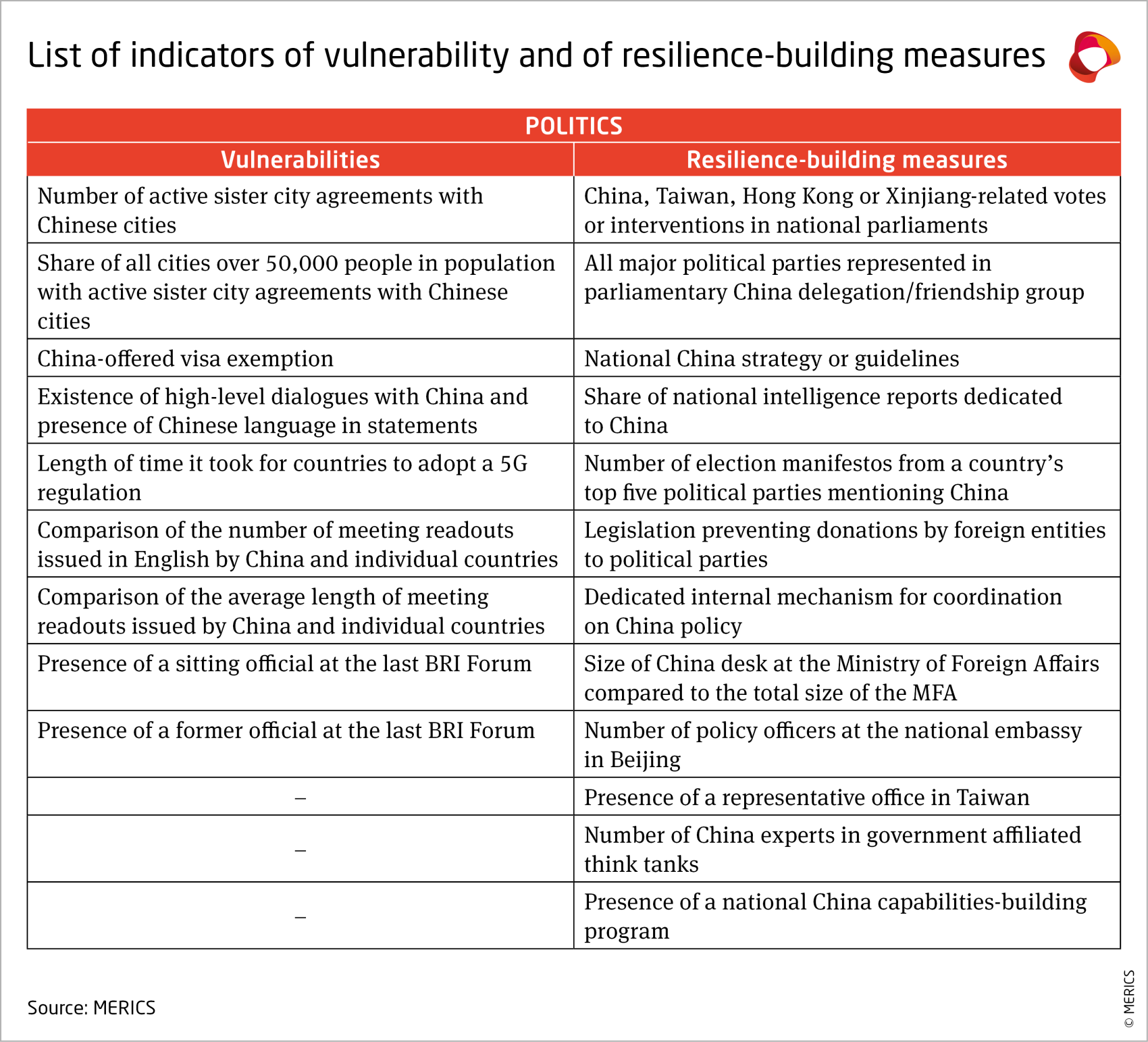

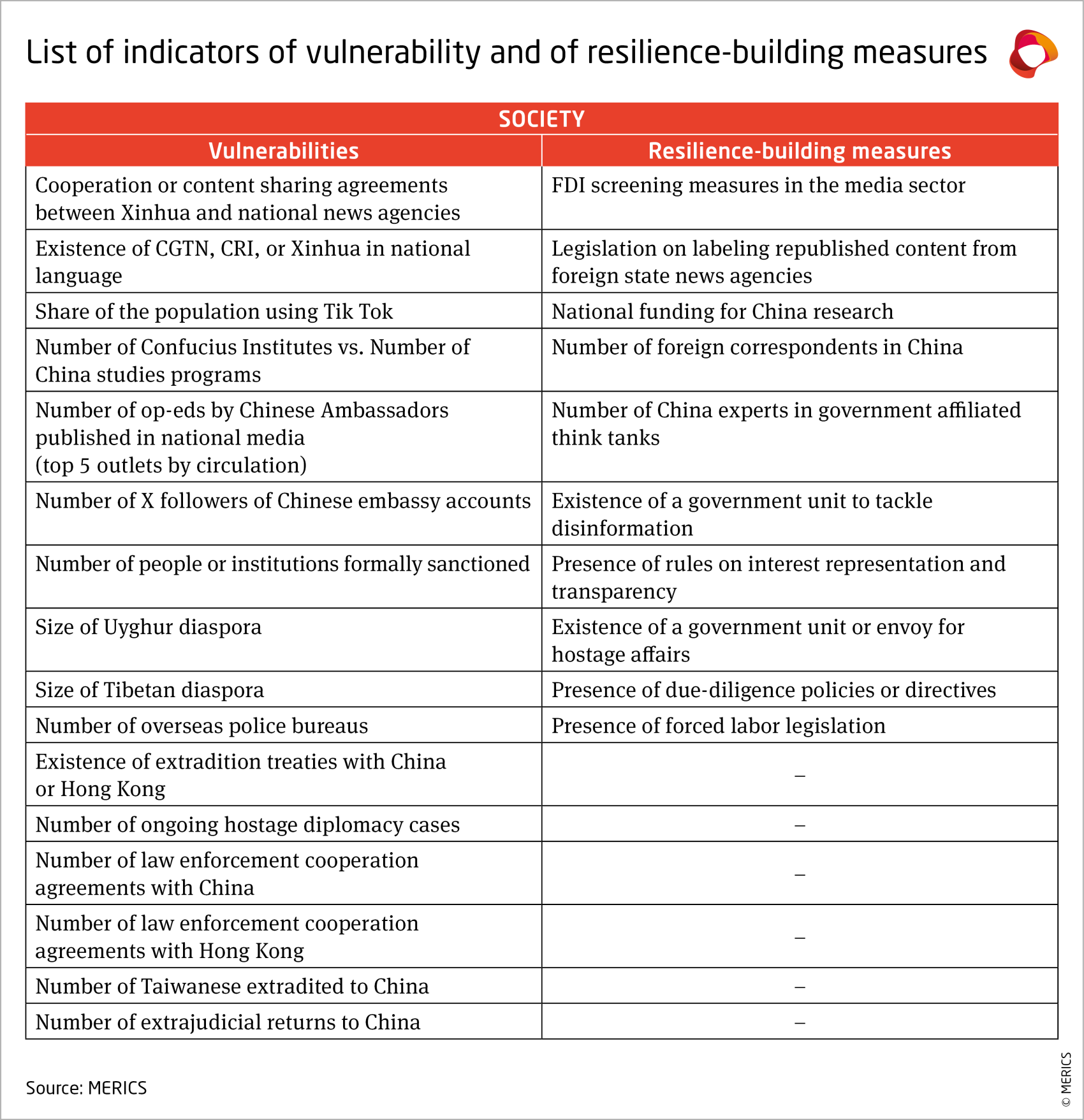

This audit was conducted based on a backend database featuring 98 indicators across four domains—economy, security, politics, and society (with technology-related indicators distributed across them given their cross-cutting relevance). It examines 10 EU countries (Czechia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden) and the United Kingdom.

The vulnerability indicators and resilience-building indicators were defined through a three-stage process that took risk-mapping as the starting point. It included discussions with and feedback from several European experts to minimize the individual biases of the authors.

- Defining risks: Identifying potential negative impacts that can be inflicted by China on Europe in reference to core European interests and the pillars of the EU's security, prosperity, and stability.

- Analyzing means: Understanding the tactics, channels and tools available to China, based on its past disruptive behaviors, and existing policy tools and legislation.

- Developing indicators: Creating indicators to assess countries' vulnerabilities to the defined means and evaluating the resilience-building measures deployed to increase the costs or hinder China’s ability to deploy those means.

The indicators were then organized into groups under four domains further differentiated into sub-groups.

- Economy: demand from China; supplies from China; Chinese investments in EU; EU investments in China.

- Security: critical infrastructure; knowledge and tech security & arms and tech transfers; military and law enforcement cooperation.

- Politics: unity and cohesion; policymaking and implementation; image and reputation.

- Society: discourse shaping; suppression of debates and interference; legitimacy and credibility.

Countries were assigned scores on the basis of their comparative vulnerability and resilience in the context of specific indicators. However, only overall scores are shared in each category, as individual indicators by themselves do not paint the full picture and the exposure of the full set of a country’s unmitigated vulnerabilities could in itself generate risks if misused.

This quantitative exercise was complemented by qualitative analyses of cross-cutting issues and dedicated national level resilience assessments towards China that help to contextualize the results. These serve to capture the ongoing political debate in which the resilience assessment is taking place both at the EU and international level, as well as within the 11 mapped countries.

The objective of this study is to help identify and grapple with the scope of the challenge that lies ahead for Europe as it builds up its resilience towards China, and to suggest some ideas for effective and realistic ways forward. The project aims to stimulate progress by highlighting both best practices and gaps in responses.

The exercise is comparative, China-specific in nature and focuses on risks linked to deliberate actions taken by China. It does not seek to assess the overall vulnerability and resilience of the covered countries in absolute terms. The benchmark score for each indicator was set by the highest vulnerability or resilience among the covered countries and is as such not applicable beyond Europe and this group of countries.

The data gathered for this exercise pertains to the period of 2019 – 2024 (with adjustments for selected indicators based on data availability or the distorting effects of extraordinary circumstances – e.g. the Covid-19 pandemic). Data was collected from publicly accessible sources and interviews. It does not include resilience-building work potentially carried out by members states internally.

Additionally, there are limits to this study’s ability to directly and objectively quantify some aspects of resilience, such as political leadership or the will to make use of existing policy tools. In some cases, this study has relied on proxy indicators to assess each country’s progress. In others, assessments must necessarily include qualitative analyses accounting for the specific conditions in each country and policy area, such as those in the country profiles releases as part of this project and reviewed by national experts.

Appendix 2: List of indicators of vulnerability and of resilience-building measures

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the colleagues who contributed to the project by sharing valuable insights, sharing their findings or providing feedback on components of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit: François Chimits and Francesca Ghiretti, Leo Clyne, Lewin Jander, Simon Nguyen, Anna-Lena Nolte, Lily Rezepa, Romano Tucci, Daniel Weise, Leonhard Xu, Carla, Zappen, Clark N. Banach and the BLOCS Lab at Aletheia Research Institution, Una Aleksandra Bērziņa-Čerenkova, Mario Esteban, Filippo Fasulo, Alicia García-Herrero, François Godement, Sam Goodman, Ingrid d'Hooghe, Jakub Jakóbowski, Björn Jerdén, Tomasz Kamiński, Joanna Ciesielska-Klikowska and Michał Gzik (Project “The Role of Cities in the European Union Policy Towards China” funded by Poland’s National Science Centre), Ivana Karásková, Támas Matura, Ludovica Meacci, Charles Parton, Alexis von Sydow and Helena Löfgren.

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

The Europe-China Resilience Audit is part of the project “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.