Hong Kong: First repress, then remold

Suppressing dissent is one thing, reworking people’s identities is another. Beijing is in for a bumpy ride, say Thomas des Garets Geddes and Katja Drinhausen.

In the eyes of the Chinese government and the administration of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s education system has been “infiltrated” and “poisoned” by anti-government forces and Western ideology. Of the 9000 or so protesters arrested since the beginning of the sustained demonstrations against the amendment of Hong Kong’s extradition laws in June last year (often referred to as anti-ELAB protests), around 4000 are said to have been students.

Hong Kong’s political youth is not new to Beijing and is often seen as part of the tainted legacy of British colonial rule. The Chinese leadership has been anxious to tackle this challenge to its power since massive protests derailed its plans to introduce moral and national education in 2012. They gave rise to a new generation of student activists like Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Agnes Chow that were vocal in the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019 protests – and are now amongst the most prominent targets under Hong Kong’s new National Security Law.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) outlined its two-pronged approach to snuff out this “political virus” in the Decision published after the Fourth Party Plenum in October of last year. The first step of this strategy – enabling targeted repression by introducing a national security law – has been successfully completed. Now comes the second step – fostering a new form of apolitical patriotism and support for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) through the reform of Hong Kong’s education system. But it looks unlikely to succeed.

Carrie Lam has promised a wide-ranging transformation of Hong Kong’s education sector

Following Beijing’s orders, Carrie Lam appears intent on re-educating her constituents to turn them into compliant and grateful citizens loyal to the CCP. According to Lam, “the wrong formulation of history and the smearing of the government and law enforcement agencies are all reflected in the teaching materials, classroom teaching, exam questions and students’ extra-curricular activities”. She has already promised a wide-ranging transformation of Hong Kong’s education sector.

The new National Anthem Ordinance requires all primary and secondary school students in Hong Kong to learn to sing the national anthem of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with proper etiquette. Anyone who misuses or insults China’s anthem faces up to three years imprisonment. Unsurprisingly, the anti-ELAB hymn “Glory to Hong Kong” was banned soon after the rules came into effect.

Schools have been required to remove all books from their libraries that – as Hong Kong’s Education Bureau puts it – “provoke any acts or activities which endanger national security”, including publications by student activist Joshua Wong. Textbooks are being censored and Lam’s government is considering scrapping the controversial Liberal Studies subject aimed at fostering critical thinking from at least part of its secondary school curricula.

The Hong Kong government is using its control of funding and political appointments to bring educational establishments to heel. In what appeared to be political retribution for their allegedly inappropriate handling of on-campus protests last year, two universities saw 32 million USD that had been allocated to them cancelled by pro-Beijing lawmakers. Alongside this, pro-establishment figures have continued to be promoted to influential roles within Hong Kong’s education system.

Teachers will be required to complete mandatory training on “national development”

From September, teachers in most of Hong Kong’s schools will be required to complete a mandatory training program focused on professional conduct and national development. Adding to such pressures and overt intimidation, some pro-Beijing politicians have gone so far as to propose installing cameras in classrooms to keep teachers in line. Arrests and removals of prominent “problem teachers” are currently making headlines and send a warning to those who might still want to use their freedom of expression in full.

The national security law’s broad reach and vague wording further amplifies the climate of uncertainty and fear among education professionals who do not know where the law draws red lines. Self-censorship is on the rise. Denunciations of teachers who – as Hong Kong’s former Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying puts it – breach “their professional codes” are now being openly encouraged. Leung recently launched a platform that gathers and publicizes information on teachers and schools that spread ideas perceived as dangerous. Rewards for such tip-offs have even been announced.

Civil liberties and the rule of law are part of Hong Kong’s DNA

Ms. Lam’s government may be succeeding in strengthening its grip on Hong Kong’s education system. But its attempt to remold its citizens identities to Beijing’s liking seems fanciful to say the least. Hong Kong is not Macau and has long since developed a strong sense of local identity. Civil liberties and the rule of law are part of the city’s DNA. Since its handover by the UK to Beijing in 1997, millions of its citizens have repeatedly taken to the streets to protect their rights and freedoms. Its youth has been at the forefront of recent protests. In a survey last December, as many as 63 percent of 18 to 29 year-olds said they had participated in the anti-ELAB protests and 87 percent expressed their support for those taking part. This shapes a generation. Ms. Lam will have a hard time erasing such values and beliefs from Hong Kong’s collective consciousness.

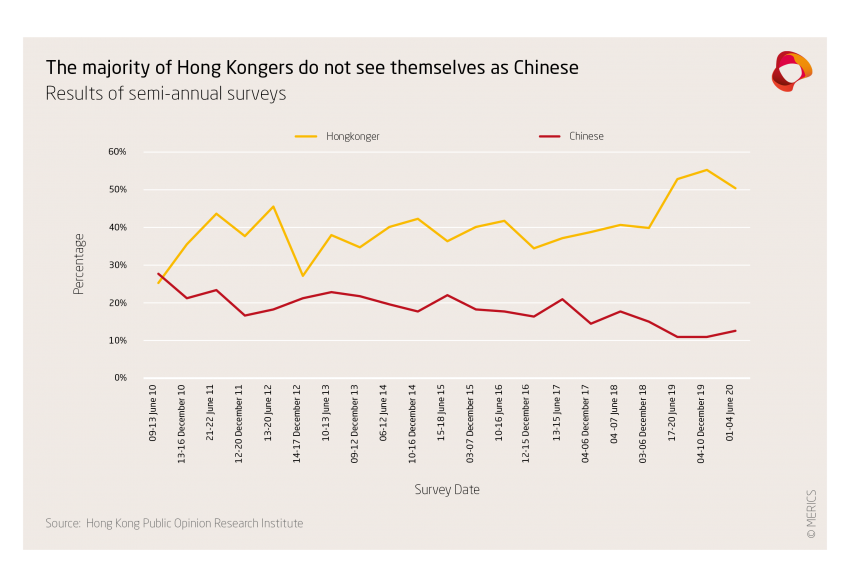

Patriotic education is not new to Hong Kong, but decades-long efforts to foster in its youth love of the motherland and fealty to Beijing have proven largely counterproductive. In line with Beijing’s calls since the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, curricula in the former British colony have gradually converged with those of the mainland and “national education” spending has soared. But to what avail? As a series of surveys suggests, in the 23 years since the handover, Hongkongers have never felt less Chinese, have never been more critical of Beijing and have never identified themselves so little as citizens of the PRC. What’s more, these feelings are even more pronounced among Hong Kong citizens under 30.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Ms. Lam may come to realize, if they have not already, that re-educating Hongkongers will require not just the promise of economic benefits, but a lot more repression and control for their soul-engineering enterprise to succeed. Reining in Hong Kong’s free press and free internet under the guise of national security are the next logical steps in Mr Xi and Ms Lam’s playbook. But, to borrow a metaphor by the father of modern Chinese literature Lu Xun, Hong Kong is no iron house without windows in which people lie fast asleep and will soon die of suffocation. Hongkongers have long since been awoken and will not go down without a protracted fight.